new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Poetic Tools, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 5 of 5

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Poetic Tools in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

by Jen Bailey

by Jen Bailey

In Part 1, we looked at how onomatopoeia and phonetic intensives can help you evoke emotion in your readers when writing emotionally detached characters. Today we will look at two additional sound-related poetic tools that can be carefully crafted to obtain your desired effect and keep your reader engaged.

Poetic Tool #3: Assonance

The long o sound we just looked at is not only an example of the use of phonetic intensives, it is also an example of assonance. Assonance is defined by Janet Burroway in Imaginative Writing: The Elements of Craft as the correspondence of vowel sounds in words.

In the following passages from Quaking, the assonance is prominent:

“leering at me, sneering” (Erskine 44)

“his oily voice” (Erskine 45)

“I see his greasy black hair” (Erskine 45)

The context of each of these lines is the presence of Matt’s bully, Rat, and she does not express her emotions at all. Instead, the repetition of vowel sounds in these examples evokes a feeling of unsteadiness and invasion – exactly what Matt must feel but can’t express.

Poetic Tool #4: Consonance

In The Sounds of Poetry, Robert Pinsky defines consonance as “a repeated consonant sound, as in ‘stroke’ and ‘ache’” (124). Erskine repeats a k/ck sound in the following passages in the context of Matt’s encounters with the Rat:

“His dark hair is rigid and sticks out at the back of his neck” (15)

“His panicked eyes flit around the parking lot” (82).

In this last example, Matt witnesses the Rat’s fear of his own father – a fear she recognizes but cannot name. The repeated k/ck sound is choppy and evokes an uneasy, jittery feeling – the kind Matt was likely experiencing in this scene.

Alliteration is a form of consonance in which there is a correspondence of consonants at the beginning of words or stressed syllables (Burroway 370). Another form of consonance is sibilance, which the Oxford English Dictionary defines as an undue prominence of the hissing s sound. Consonance can have a magnifying effect when writers carefully craft their sentences. In the following sentence from Quaking, a general play with consonant sounds results in a very sinister-sounding section:

‘“Chicken-shit!’ the Rat yells in my face, and I clutch my chest but I leave a chink exposed and his elbow catches my rib. He shoves me and I fall to the floor” (Erskine 217).

The hissing “s” and “sh” sounds are sibilant:

shit yells face chest exposed catches

The ‘ch’ sound alliterates at the beginning and middle of some words,

chicken clutch chest chink catches

furthermore, consonance is developed with the “t” sound,

shit Rat chest

and the “k/ck” sound,

chicken chink

These sounds all echo each other, thereby increasing the menacing nature of this passage. Because of careful word choices the reader gets the feeling of fear and loss of control that the emotionally detached protagonist either does not admit to or cannot describe.

Poets rely on the sounds of language to evoke emotion in their readers. Onomatopoeia, phonetic intensives, assonance, consonance are among the many tools they use to achieve this. While these tools will beautify and intensify prose with any kind of character, poetic language is especially invaluable for evoking the emotion that ventures beyond the emotional vocabulary and awareness of those characters who are emotionally detached.

Be sure you didn’t miss the first half of this article: Engaging the Heart – Part 1

Jen Bailey lives in Ottawa, Ontario and has a Master of Fine Arts degree in Writing for Children and Young Adults from Vermont College of Fine Arts. She loves playing around with rhythm and sound in her writing. Should you like that kind of thing too, she recommends you read Quaking by Kathryn Erskine, Last Night I Sang to the Monster by Benjamin Alire Saenz, Meg Rosoff’s How I Live Now, and any poetry you can get your hands on.

Jen Bailey lives in Ottawa, Ontario and has a Master of Fine Arts degree in Writing for Children and Young Adults from Vermont College of Fine Arts. She loves playing around with rhythm and sound in her writing. Should you like that kind of thing too, she recommends you read Quaking by Kathryn Erskine, Last Night I Sang to the Monster by Benjamin Alire Saenz, Meg Rosoff’s How I Live Now, and any poetry you can get your hands on.

Follow her musings on writers’ craft and the writing life at writefiercely.wordpress.com

This blog post was brought to you as part of the March Dystropian Madness Blog Series.

Sources:

Burroway, Janet. Imaginative Writing: The Elements of Craft. Boston: Longman, 2010. Print.

Erskine, Kathryn. Quaking. New York: Philomel Books, 2007. Print.

Pinsky, Robert. The Sounds of Poetry: A Brief Guide. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1999. Print.

by Jen Bailey

by Jen Bailey

As writers who are true to our characters, we allow them to express themselves as they are able. We typically rely on actions, dialogue, physical reactions, and thoughts to do this, but what’s a writer to do when the character in question is emotionally detached, that is, unaware of his or her emotions?

Writing emotionally unaware characters can be challenging because they are unable to communicate their feelings about what would normally be viewed as emotionally-charged incidents. This kind of detachment can be all-encompassing (e.g. a result of psychological trauma: abuse, neglect, abandonment), or transient (e.g. hearing very jarring news). The character may also have a highly intellectual and logical personality and not be attuned to their own emotion. No matter what the source of detachment, if not handled carefully, there is a great chance of losing your reader if they can’t become, or stay, emotionally engaged in your story.

In part one of this blog post, I’ll discuss a couple of ways in which you can engage your reader’s heart all while staying true to your emotionally detached character. Using examples from the novel Quaking by Kathryn Erskine, I’ll show you how you can evoke the emotion your character cannot express through the use of sound-related poetic language.

Poetic Tool #1: Onomatopoeia

Onomatopoetic words sound like their meanings and call to mind images and/or feelings for the reader. The use of these words is powerful but limited, as they can only be used to describe sounds. Here are some examples of onomatopoetic words – pay attention to what they evoke in you as you read them: ring, hiss, clatter, bang, grunt, slam, and snap.

In Quaking, Matt, an emotionally detached character, is taunted by a bully she nicknamed “Rat.” Erskine describes Matt’s encounter with the Rat as follows:

“I smell his smoke. His sneer and hiss are quiet but still forceful. ‘You’re dead…Quaker!’” (Erskine 217, emphasis added).

The words sneer and hiss are onomatopoetic. They imitate the dark, sinister sound of Rat’s voice for the reader. The reader thus feels Matt’s emotion, even though she cannot express it.

Poetic Tool #2: Phonetic Intensives

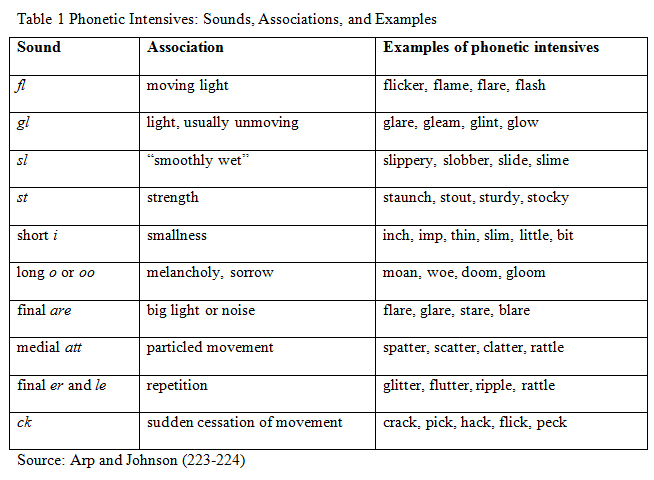

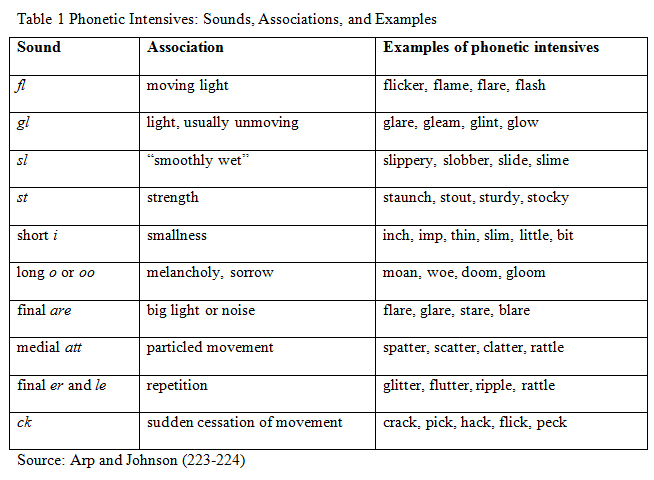

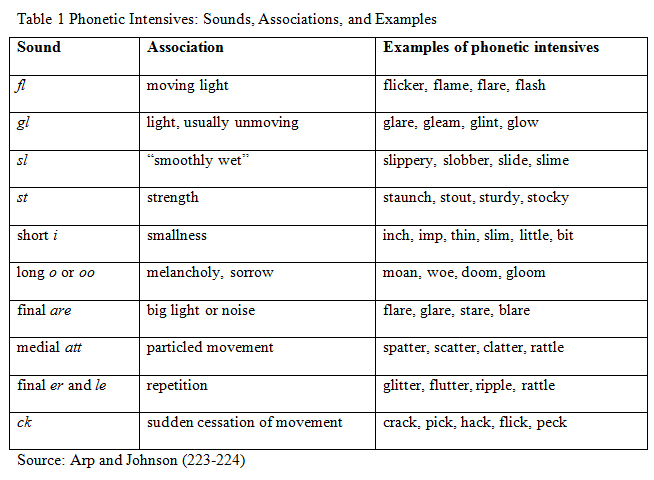

Arp and Johnson define phonetic intensives as words “whose sound … to some degree connects to their meaning.” Here are some examples:

It is important to note that while these phonetic intensives can contribute to meaning, they are not in themselves prescriptive of meaning. For example, many words that begin with the ‘fl’ sound can be associated with moving light, but there are many others that have nothing at all to do with that association: think flower, flounder, flask, flamingo. Phonetic intensives must be used judiciously.

Let’s look at an example where they are used well:

I am cold all over. He knows. I am dead. It is really over. (Erskine 217)

The long o sound creates a feeling of a moan coming from Matt and to the ear of the reader. It is like a lament and can place the reader with Matt, evoking the sorrow and melancholy Matt is not expressing in this scene.

While the use of onomatopoeia and phonetic intensives is somewhat limited, the sound-related poetic tools I will be discussing in part 2 can be more carefully crafted to obtain your desired effect and keep your reader engaged.

Stay tuned!

Jen Bailey lives in Ottawa, Ontario and has a Master of Fine Arts degree in Writing for Children and Young Adults from Vermont College of Fine Arts. She loves playing around with rhythm and sound in her writing. Should you like that kind of thing too, she recommends you read Quaking by Kathryn Erskine, Last Night I Sang to the Monster by Benjamin Alire Saenz, Meg Rosoff’s How I Live Now, and any poetry you can get your hands on.

Jen Bailey lives in Ottawa, Ontario and has a Master of Fine Arts degree in Writing for Children and Young Adults from Vermont College of Fine Arts. She loves playing around with rhythm and sound in her writing. Should you like that kind of thing too, she recommends you read Quaking by Kathryn Erskine, Last Night I Sang to the Monster by Benjamin Alire Saenz, Meg Rosoff’s How I Live Now, and any poetry you can get your hands on.

Follow her musings on writers’ craft and the writing life at writefiercely.wordpress.com

This blog post was brought to you as part of the March Dystropian Madness Blog Series.

Sources:

Arp, Thomas R. and Greg Johnson. Perrine’s Sound and Sense: An Introduction to Poetry. 11th ed. Boston, Mass.: Thomson/Wadsworth, 2005. Print.

Erskine, Kathryn. Quaking. New York: Philomel Books, 2007. Print.

by Jen Bailey

by Jen Bailey

As writers who are true to our characters, we allow them to express themselves as they are able. We typically rely on actions, dialogue, physical reactions, and thoughts to do this, but what’s a writer to do when the character in question is emotionally detached, that is, unaware of his or her emotions?

Writing emotionally unaware characters can be challenging because they are unable to communicate their feelings about what would normally be viewed as emotionally-charged incidents. This kind of detachment can be all-encompassing (e.g. a result of psychological trauma: abuse, neglect, abandonment), or transient (e.g. hearing very jarring news). The character may also have a highly intellectual and logical personality and not be attuned to their own emotion. No matter what the source of detachment, if not handled carefully, there is a great chance of losing your reader if they can’t become, or stay, emotionally engaged in your story.

In part one of this blog post, I’ll discuss a couple of ways in which you can engage your reader’s heart all while staying true to your emotionally detached character. Using examples from the novel Quaking by Kathryn Erskine, I’ll show you how you can evoke the emotion your character cannot express through the use of sound-related poetic language.

Poetic Tool #1: Onomatopoeia

Onomatopoetic words sound like their meanings and call to mind images and/or feelings for the reader. The use of these words is powerful but limited, as they can only be used to describe sounds. Here are some examples of onomatopoetic words – pay attention to what they evoke in you as you read them: ring, hiss, clatter, bang, grunt, slam, and snap.

In Quaking, Matt, an emotionally detached character, is taunted by a bully she nicknamed “Rat.” Erskine describes Matt’s encounter with the Rat as follows:

“I smell his smoke. His sneer and hiss are quiet but still forceful. ‘You’re dead…Quaker!’” (Erskine 217, emphasis added).

The words sneer and hiss are onomatopoetic. They imitate the dark, sinister sound of Rat’s voice for the reader. The reader thus feels Matt’s emotion, even though she cannot express it.

Poetic Tool #2: Phonetic Intensives

Arp and Johnson define phonetic intensives as words “whose sound … to some degree connects to their meaning.” Here are some examples:

It is important to note that while these phonetic intensives can contribute to meaning, they are not in themselves prescriptive of meaning. For example, many words that begin with the ‘fl’ sound can be associated with moving light, but there are many others that have nothing at all to do with that association: think flower, flounder, flask, flamingo. Phonetic intensives must be used judiciously.

Let’s look at an example where they are used well:

I am cold all over. He knows. I am dead. It is really over. (Erskine 217)

The long o sound creates a feeling of a moan coming from Matt and to the ear of the reader. It is like a lament and can place the reader with Matt, evoking the sorrow and melancholy Matt is not expressing in this scene.

While the use of onomatopoeia and phonetic intensives is somewhat limited, the sound-related poetic tools I will be discussing in part 2 can be more carefully crafted to obtain your desired effect and keep your reader engaged.

Stay tuned!

Jen Bailey lives in Ottawa, Ontario and has a Master of Fine Arts degree in Writing for Children and Young Adults from Vermont College of Fine Arts. She loves playing around with rhythm and sound in her writing. Should you like that kind of thing too, she recommends you read Quaking by Kathryn Erskine, Last Night I Sang to the Monster by Benjamin Alire Saenz, Meg Rosoff’s How I Live Now, and any poetry you can get your hands on.

Jen Bailey lives in Ottawa, Ontario and has a Master of Fine Arts degree in Writing for Children and Young Adults from Vermont College of Fine Arts. She loves playing around with rhythm and sound in her writing. Should you like that kind of thing too, she recommends you read Quaking by Kathryn Erskine, Last Night I Sang to the Monster by Benjamin Alire Saenz, Meg Rosoff’s How I Live Now, and any poetry you can get your hands on.

Follow her musings on writers’ craft and the writing life at writefiercely.wordpress.com

This blog post was brought to you as part of the March Dystropian Madness Blog Series.

Sources:

Arp, Thomas R. and Greg Johnson. Perrine’s Sound and Sense: An Introduction to Poetry. 11th ed. Boston, Mass.: Thomson/Wadsworth, 2005. Print.

Erskine, Kathryn. Quaking. New York: Philomel Books, 2007. Print.

By: Kathy Temean,

on 6/27/2011

Blog:

Writing and Illustrating

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Writing Tips,

reference,

Process,

Similes,

Metaphors,

Writing Picture Books,

Poetic Tools,

Personification,

need to know,

demystify,

Add a tag

Last week we talked about a few poetic tools you could use while writing. Here are a few more:

Last week we talked about a few poetic tools you could use while writing. Here are a few more:

METAPHOR:

This is when a writer says one thing, but actually is saying something else. Floyd Cooper speaks in metaphor in Coming Home: From the Life of Langston Hughes when he calls a train the old iron snake.

SIMILE:

Here the writer compares one thing to another with the word like or as. Example: I was as mad as the bumblebee Ferdinand sat on. My friend Eileen Spinelli is great at using similes. Here’s one from Something to Tell the Grandcows. Emmadine has travel to the South Pole and “Her teeth chattered like spoons.” Or how about this one from Rupa Raises the Sun by Marsha Wilson Chall, “the sun broke across the sky like an egg yolk.”

Ann Whitford Paul says in Writing Picture Books, “We write in metaphor and simile to give the reader a visual image instead of a plain description. ” Metaphors and Similes cut down on the words that would be necessary to describe what we want to say. This is a great tool for the picture book writer, especially, because editors are wanting shorter and shorter picture books. This is what Ann does when she want to create a unique, visual, and tone-perfect Metaphor or simile. She numbers a piece of paper from 1 to 10 and then she free associates until she has 10 possibilities. If she doesn’t like any of them, she continues 11 to 20 and keeps going until she creates one that seems perfect. Do I hear a few groans?

PERSONIFICATION:

With this tool we give human characteristics to something that is not human. If I say, “The book held me in its grasp all the way to the last page.” Everyone knows what I mean, even though books do not have arms. How about? “The icy finger of winter slipped down my shirt.” Winter doesn’t have fingers.

Want to try your hand at identifying the metaphors, similes and personifications below?

1. The moon is a bowl of breakfast cereal.

2. I ran, but danger ran faster.

3. Ryan didn’t want to go to Katie’s party, so he moved slow as a snail.

4. Jacob felt like a rabbit caught in a trap.

5. The tree is our umbrella, keeping us dry from the rain.

6. The quilt spoke stories of love and loss.

ANSWERS: 1. Metaphor 2. Personification 3. Simile 4. Simile 5. Metaphor 6. Personification

HOMEWORK: Now pull out that same manuscript from last week and read it through again. Did you use any of theses techniques? Do you see a place where you could use one of these tools to make your story more interesting or maybe even cut out a few words or lines? Give it a try. What do you have to lose?

Talk tomorrow,

Kathy

Filed under:

demystify,

need to know,

Process,

reference,

Writing Tips Tagged:

Metaphors,

Personification,

Poetic Tools,

Similes,

Display Comments

A Poet’s Toolbox

Originally uploaded by teachergal

We read Valerie Worth’s “Chairs” Poem today prior to Writing Workshop. Before my kids filled out the revised Responding to Poetry Form, we spent time really talking about tools poets use (i.e., they keep all of these in their [...]

Jen Bailey lives in Ottawa, Ontario and has a Master of Fine Arts degree in Writing for Children and Young Adults from Vermont College of Fine Arts. She loves playing around with rhythm and sound in her writing. Should you like that kind of thing too, she recommends you read Quaking by Kathryn Erskine, Last Night I Sang to the Monster by Benjamin Alire Saenz, Meg Rosoff’s How I Live Now, and any poetry you can get your hands on.

Jen Bailey lives in Ottawa, Ontario and has a Master of Fine Arts degree in Writing for Children and Young Adults from Vermont College of Fine Arts. She loves playing around with rhythm and sound in her writing. Should you like that kind of thing too, she recommends you read Quaking by Kathryn Erskine, Last Night I Sang to the Monster by Benjamin Alire Saenz, Meg Rosoff’s How I Live Now, and any poetry you can get your hands on.

Last week we talked about a few poetic tools you could use while writing. Here are a few more:

Last week we talked about a few poetic tools you could use while writing. Here are a few more:

The two blogs about poetic tools are amazing. The examples make the lesson sink in effortlessly. Thank you to both of you!

Once again, great examples. I’m revising my WIP, so this is a good time to pay attention to these techniques.

Thank you Anna and L. Marie! Glad you’ve found them to be helpful. Happy writing!

Wonderful! Clear and concise. Thank you.