This week I convened a philosophy seminar in Oxford with Kasia de Lazari-Radek and Peter Singer. Singer is probably the world’s most famous living philosopher, well known for his pioneering work on the ethics of our treatment of non-human animals, on global poverty, and on many other issues. Less well known, perhaps, is the fact that Singer has recently changed his mind on the question of what really matters. I’m talking here about what matters for individual beings – what makes their lives good or bad for them.

The post Is pleasure all that matters? appeared first on OUPblog.

I call myself a moral philosopher. However, I sometimes worry that I might actually be an immoral philosopher. I worry that there might be something morally wrong with making the arguments I make. Let me explain.

When it comes to preventing poverty related deaths, it is almost universally agreed that Peter Singer is one of the good guys. His landmark 1971 article, “Famine, Affluence and Morality” (FAM), not only launched a rich new area of philosophical discussion, but also led to millions in donations to famine relief. In the month after Singer restated the argument from FAM in a piece in the New York Times, UNICEF and OXFAM claimed to have received about $660, 000 more than they usually took in from the phone numbers given in the piece. His organisation, “The Life You Can Save”, used to keep a running estimate of total donations generated. When I last checked the website on 13th February 2012, this figure stood at $62, 741, 848.

Singer argues that the typical person living in an affluent country is morally required to give most of his or her money away to prevent poverty related deaths. To fail to give as much as you can to charities that save children dying of poverty is every bit as bad as walking past a child drowning in a pond because you don’t want to ruin your new shoes. Singer argues that any difference between the child in the pond and the child dying of poverty is morally irrelevant, so failure to help must be morally equivalent. For an approachable version of his argument see Peter Unger, who developed and refined Singer’s arguments in his 1996 book, Living High and Letting Die.

I’ve argued that Singer and Unger are wrong: failing to donate to charity is not equivalent to walking past a drowning child. Morality does – and must – pay attention to features such as distance, personal connection and how many other people are in a position to help. I defend what seems to me to be the commonsense position that while most people are required to give much more than they currently do to charities such as Oxfam, they are not required to give the extreme proportions suggested by Singer and Unger.

So, Singer and Unger are the good guys when it comes to debates on poverty-related death. I’m arguing that Singer and Unger are wrong. I’m arguing against the good guys. Does that make me one of the bad guys? It is true that my own position is that most people are required to give more than they do. But isn’t there still something morally dubious about arguing for weaker moral requirements to save lives? Singer and Unger’s position is clear and easy to understand. It offers a strong call to action that seems to actually work – to make people put their hands in their pockets. Isn’t it wrong to risk jeopardising that given the possibility that people will focus only on the arguments I give against extreme requirements to aid?

On reflection, I don’t think what I do is immoral philosophy. The job of moral philosophers is to help people to decide what to believe about moral issues on the basis of reasoned reflection. Moral philosophers provide arguments and critique the arguments of others. We won’t be able to do this properly if we shy away from attacking some arguments because it is good for people to believe them.

In addition, the Singer/Unger position doesn’t really offer a clear, simple conclusion about what to do. For Singer and Unger, there is a nice simple answer about what morality requires us to do: keep giving until giving more would cost us something more morally significant than the harm we could prevent; in other words, keep giving till you have given most of your money away. However, this doesn’t translate into a simple answer about what we should do, overall. For, on Singer’s view, we might not be rationally required or overall required to do what we are morally required to.

This need to separate moral requirements from overall requirements is a result of the extreme, impersonal view of morality espoused by Singer. The demands of Singer’s morality are so extreme it must sometimes be reasonable to ignore them. A more modest understanding of morality, which takes into account the agent’s special concern with what is near and dear to her, avoids this problem. Its demands are reasonable so cannot be reasonably ignored. Looked at in this way, my position gives a clearer and simpler answer to the question of what we should do in response to global poverty. It tells us both what is morally and rationally required. Providing such an answer surely can’t be immoral philosophy.

Headline image credit: Devil gate, Paris, by PHGCOM (Own work). CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Immoral philosophy appeared first on OUPblog.

By Katarzyna de Lazari-Radek and Peter Singer

We are constantly making decisions about what we ought to do. We have to make up our own minds, but does that mean that whatever we choose is right? Often we make decisions from a limited or biased perspective.

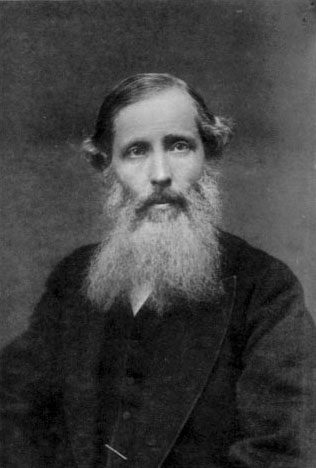

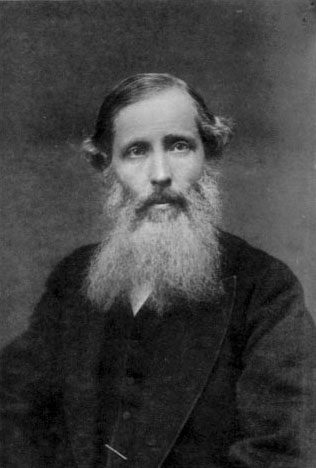

The nineteen century utilitarian philosopher Henry Sidgwick thought that it is possible for us to reach, by means of reasoning, an objective standpoint that is detached from our own perspective. He called it “the point of view of the universe”. We used this phrase as the title of our book, which is a defense of Sidgwick’s general approach to ethics and to utilitarianism. On one important problem we suggest a correction that we believe makes it possible to overcome a difficulty that greatly troubled him.

We argue that reason is capable of presenting us with objective, impartial, non-natural reasons for action. We agree with Sidgwick that only the presupposition that reasons are objective enables us to make sense of the disagreements we have with other people about what we ought to do, and the way in which we respond to them by presenting them with reasons for our views. Those who deny that we can have objective reasons for action claim that all reasons for action start from desires or preferences.

If we were to accept this view, we would also have to accept that if we have no preferences about the welfare of distant strangers, or of animals, or of future generations, then we have no reason to do anything to help them, or to avoid harming them (as, for example, we are harming future generations by continuing to emit greenhouse gases). We hold that people do have reasons to help distant strangers, animals, and future generations, irrespective of our preferences regarding their welfare.

If objective moral reasoning is possible, how does it get started? Sidgwick’s answer is, in brief, that it starts with a self-evident intuition. He does not mean by this, however, the intuitions of what he calls “common sense morality.” To see what he does mean, we must draw a distinction between intuitions that are self-evident truths of reason, and a very different kind of intuition. This distinction will become clearer if we look at an objection to the idea of moral intuition as a source of moral truth.

If objective moral reasoning is possible, how does it get started? Sidgwick’s answer is, in brief, that it starts with a self-evident intuition. He does not mean by this, however, the intuitions of what he calls “common sense morality.” To see what he does mean, we must draw a distinction between intuitions that are self-evident truths of reason, and a very different kind of intuition. This distinction will become clearer if we look at an objection to the idea of moral intuition as a source of moral truth.

Sidgwick was a contemporary of Charles Darwin, so it is not surprising that already in his time the objection was raised that an evolutionary view of the origins of our moral judgments would completely discredit them. Sidgwick denied that any theory of the origins of our capacity for making moral judgments could discredit the very idea of morality, because he thought that no matter what the origin of our moral judgments, we will still have to decide what we ought to do, and answering that question is a worthwhile enterprise.

On the other hand, he agreed that some accounts of the origins of particular moral judgments might suggest that they are unlikely to be true, and therefore discredit them. We defend this important insight, and press it further. Many of our common and widely shared moral intuitions are the outcome of evolutionary selection, but the fact that they helped our ancestors to survive and reproduce does not show them to be true.

This might be taken as a ground for skepticism about morality as a whole, but our capacity for reasoning saves morality from this skeptical critique. The ability to reason has, of course, evolved, and clearly confers evolutionary advantages on those who possess it, but it does so by making it possible for us to discover the truth about our world, and this includes the discovery of some non-natural moral truths.

Sidgwick thought that his greatest work was a failure because it concluded by accepting that both egoism and universal benevolence were rational. Yet they pointed to different conclusions about what we ought to do. We argue that the evolutionary critique of some moral intuitions can be applied to egoism, but not to universal benevolence. The principle of universal benevolence can be seen as self-evident, once we understand that our own good is, from “the point of view of the universe” of no more importance than the similar good of anyone else. This is a rational insight, not an evolved moral intuition.

In this way, we resolve the so-called “dualism of practical reason.” This leaves us with a utilitarian reason for action that can be presented in the form of a utilitarian principle: we ought to maximize the good generally.

What is this good thing that we should maximize? Is my having a positive attitude towards something enough to make bringing it about good for me? Preference utilitarians have argued that it is, and one of us has, for many years, been well-known as a representative of that view.

Sidgwick, however, rejected such theories, arguing that the good must be, not what I actually desire but what I would desire if I were thinking rationally. He then develops the view that the only things that it is rational to desire for themselves are desirable mental states, or pleasure, and the absence of pain.

For those who hold that practical reasoning must start from desires, it is hard to understand the idea of what it would be rational to desire – or at least, that idea can be understood only in relation to other desires that the agent may have, so as to produce a greater harmony of desire.

This leads to a desire-based theory of the good.

One of us, for many years, became well-known as a defender of one such desire-based theory, namely preference utilitarianism. But if reason can take us to a more universal perspective, then we can understand the claim that it would be rational for us to desire some goods, even if we have no present desire for them. On that basis, it becomes more plausible to argue for the view that the good consists in having certain mental states, rather than in the satisfaction of desires or preferences.

Katarzyna de Lazari-Radek is a Polish utilitarian philosopher, working as an assistant professor at the Institute of Philosophy at the University of Lodz. Peter Singer is Ira W. DeCamp Professor of Bioethics at Princeton University, and a Laureate Professor at the Centre for Applied Philosophy and Public Ethics at the University of Melbourne; in 2005 Time magazine named him one of the 100 most influential people in the world. Katarzyna de Lazari-Radek and Peter Singer are authors of The Point of View of the Universe.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only philosophy articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Henry Sidgwick. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The point of view of the universe appeared first on OUPblog.

If objective moral reasoning is possible, how does it get started? Sidgwick’s answer is, in brief, that it starts with a self-evident intuition. He does not mean by this, however, the intuitions of what he calls “common sense morality.” To see what he does mean, we must draw a distinction between intuitions that are self-evident truths of reason, and a very different kind of intuition. This distinction will become clearer if we look at an objection to the idea of moral intuition as a source of moral truth.

If objective moral reasoning is possible, how does it get started? Sidgwick’s answer is, in brief, that it starts with a self-evident intuition. He does not mean by this, however, the intuitions of what he calls “common sense morality.” To see what he does mean, we must draw a distinction between intuitions that are self-evident truths of reason, and a very different kind of intuition. This distinction will become clearer if we look at an objection to the idea of moral intuition as a source of moral truth.

I think it's about time we commit utilitarianism - or at least it's foundation upon 'happiness' - to the history books.

My main reason is that happiness is not necessarily good. Utilitarians already know this, yet on they march. Please, utilitarians, please stop.