If your experience of school music was anything like mine, you’ll recall those dreaded aural lessons when the teacher put on a recording and instructed you to identify the instruments, to describe the main melody, to spot a key change, perhaps even to name the composer.

The post Learning to listen appeared first on OUPblog.

For many years, scholarship on composer Gustav Mahler’s life and work has relied heavily on Natalie Bauer-Lechner’s diary. However, a recently discovered letter, introduced, translated, and annotated by Morten Solvik and Stephen E. Hefling, and published for the first time in the journal The Musical Quarterly, sheds new light on the private life of the great composer. New revelations about various relationships, including Bauer-Lechner’s romantic involvement with the composer, sketch out his personal character and provide a more nuanced portrait. We spoke with Morten Solvik and Stephen E. Hefling about the impact on Mahler scholarship.

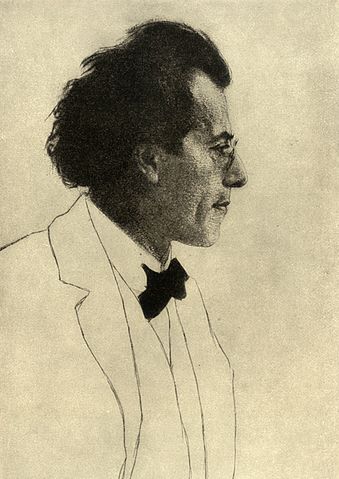

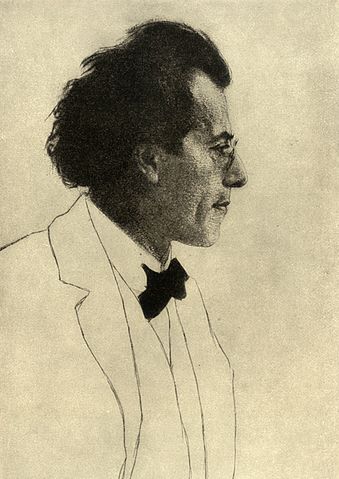

Gustav Mahler, photo of the etching by Emil Orlik (1903), in the Groves Dictionary and New Outlook (1907). Collections Walter Anton. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Natalie Bauer-Lechner is the primary witness to roughly 10 years of Gustav Mahler’s life; biographers and historians have continually relied on her accounts to shed light on Mahler’s works and thoughts, especially during the 1890s. In this letter, three main topics are discussed in ways never before documented in Mahler studies: (1) Mahler’s various romantic involvements before his marriage to Alma Schindler in 1902; (2) the role of Justine Mahler, the composer’s sister, in his personal interactions with these women; and (3) Natalie Bauer-Lechner’s two brief periods of sexual relations with Mahler, at the beginning and at the end of her 12-year relationship.

The implications go beyond the merely biographical, as it reveals the author in a liaison – long-suspected by some scholars – with the object of her recollections. How, then, do we evaluate her writings? How trustworthy is the information they claim to provide? Since Bauer-Lechner has heretofore been considered absolutely reliable, the ramifications of a revision of this stance could have far-reaching consequences.

How was this letter discovered, and what kept it from being published for so long?

The letter had been in private hands until it appeared in the shop of a Viennese rare books dealer and was sold to the Music Collection of the Austrian National Library in the fall of 2012. The authors first became aware of the document in the spring of 2012 when it became known that the owner had attempted (unsuccessfully) to sell the letter through the Dorotheum Auction House in Vienna in May 2011. How the letter ended up in this person’s possession has not (yet) been determined. Its authenticity is firmly established.

Does the publication of this letter vindicate, or just as equally cast into doubt, any previously published writing on Mahler?

This depends on one’s perspective. Some will conclude that Bauer-Lechner’s romantic interludes with the composer precluded any objectivity in her recollections of him and that her accounts must therefore be called into question. Others will point out that Bauer-Lechner’s diaries include much factual information corroborated by many other sources and that there is little reason to doubt the authenticity of her “Mahleriana” as a whole; indeed, her degree of objectivity is all the more remarkable given her emotional involvement. For discretion’s sake she declined to reveal the extent of her intimacy with Mahler in the pages of her diary that she intended to publish. But that Bauer-Lechner manipulated or fabricated information seems a contrived conclusion; that she was unable to avoid a certain partiality or missed certain details should hardly strike us as surprising.

Does the letter pose any new questions for future Mahler scholars?

The most imposing and immediate challenge that emerges from this letter is the need to collate all extant materials that Natalie Bauer-Lechner produced in her lifetime in connection with Gustav Mahler. The present authors are in the midst of precisely this project in an attempt to present the most complete account possible. This will facilitate a better informed evaluation of the value of her narrative, the extent of its objectivity, its shortcomings, and no doubt more information regarding Mahler. In particular, the content of the letter clearly indicates the need to reevaluate Alma Mahler’s claim that at the time of their marriage, Mahler “was extremely puritanical” and “had lived the life of an ascetic.”

Morten Solvik and Stephen E. Hefling are the authors of “Natalie Bauer-Lechner on Mahler and Women: A Newly Discovered Document” in the Musical Quarterly. Morten Solvik is the Center Director of the International Education of Students (IES) Abroad Vienna where he also teaches music history. Stephen E. Hefling is a Professor of Music at Case Western Reserve University.

The Musical Quarterly, founded in 1915 by Oscar Sonneck, has long been cited as the premier scholarly musical journal in the United States. Over the years it has published the writings of many important composers and musicologists, including Aaron Copland, Arnold Schoenberg, Marc Blitzstein, Henry Cowell, and Camille Saint-Saens. The journal focuses on the merging areas in scholarship where much of the challenging new work in the study of music is being produced.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post New questions about Gustav Mahler appeared first on OUPblog.

By Christopher Wiley

The 8th May marks the seventieth anniversary of the death of Dame Ethel Smyth (1858-1944), the pioneering composer and writer, at her home in Hook Heath, near Woking. In the course of her long and varied career, she composed six operas and an array of chamber, orchestral, and vocal works, challenging traditional notions of the place of women within music composition. In her later years she found a second calling as an author of auto/biographical and polemical writings, publishing ten books between 1919 and 1940.

Smyth led a fascinating and unconventional life. Having resolved at an early age to enter the music profession, she overcame opposition from her father (an army general) in order to enrol at the Leipzig Conservatorium in 1877. During her years in Continental Europe she came into contact with Brahms, Clara Schumann, Grieg, and Chaikovsky. Returning to England in the late 1880s, her compositions attracted much attention in the years and decades that followed, from influential figures including Empress Eugénie, Lady Mary Ponsonby, Queen Victoria, Princesse de Polignac, and, in the field of music, Thomas Beecham, Bruno Walter, Adrian Boult, Henry Wood, Donald Tovey, and George Bernard Shaw. She received honorary doctorates from the Universities of Durham and Oxford, and was awarded the DBE in 1922.

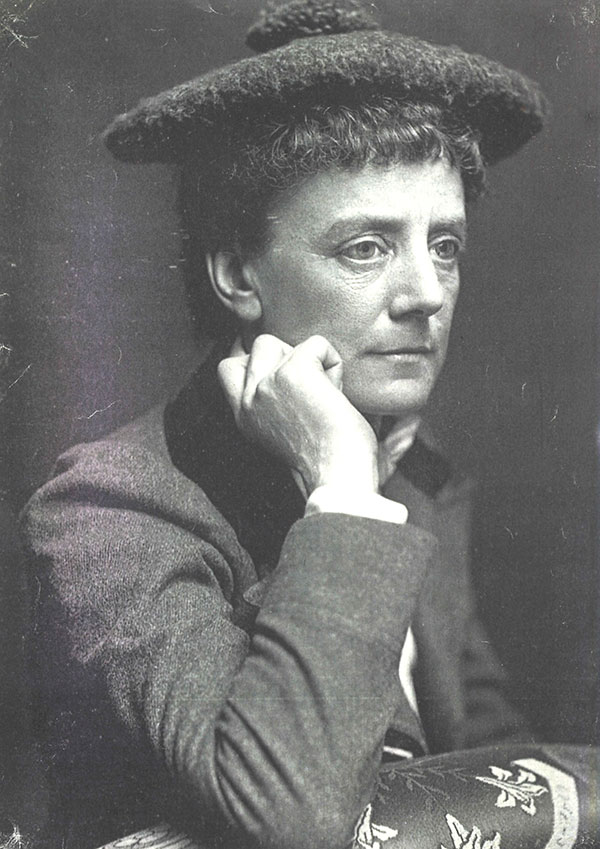

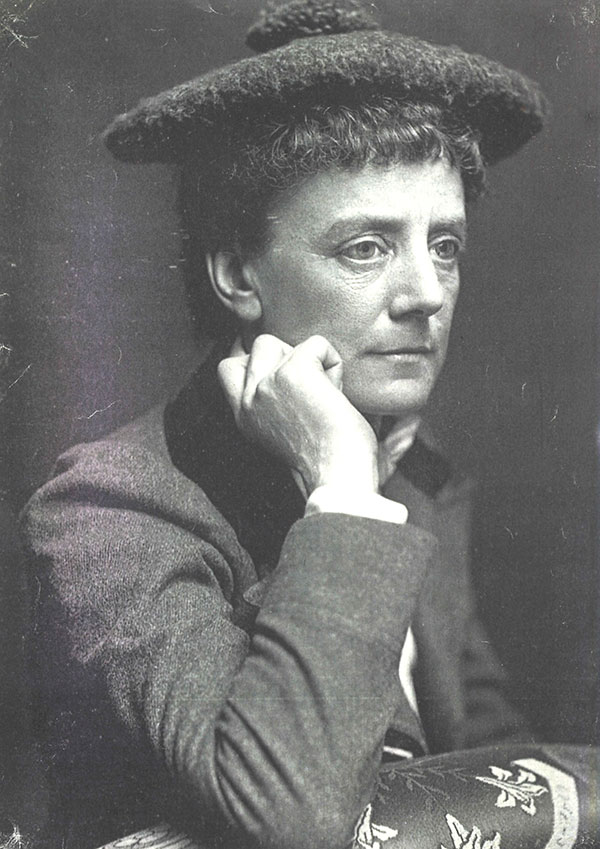

Ethel Smyth, 1908. Lewis Orchard Collection Ref.9180, courtesy of Surrey History Centre.

This intriguing artist has been a subject of my research for over a decade, leading to my article “Music and Literature: Ethel Smyth, Virginia Woolf, and ‘The First Woman to Write an Opera’” recently published in The Musical Quarterly (itself a companion-piece to an article I published in another Oxford journal, Music & Letters, in 2004). My particular interest lies in Smyth’s relationship with the novelist Virginia Woolf (1882-1941), whom she befriended in 1930 and with whom she maintained a lively correspondence that provides many valuable insights into Smyth’s activities as memoirist and polemicist, and, more widely, into the differences between their respective disciplines.

Smyth may not have been the first ever woman to write an opera, as Woolf erroneously suggested in the quotation that inspired my article (that distinction goes to Francesca Caccini, over 250 years earlier). But she was nonetheless a pathbreaking individual in many different respects. To commemorate the anniversary of her passing, here follow five facts about Ethel Smyth, some well known, others less so, illustrating ways in which she made history in music, politics, and literature.

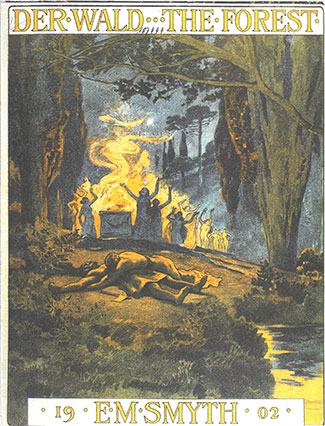

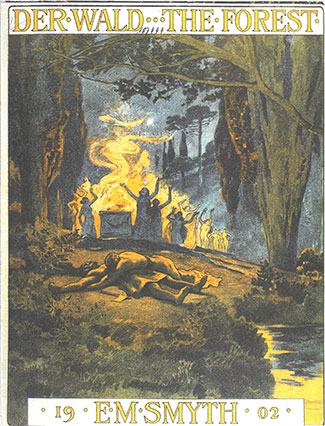

Front cover of Ethel Smyth Der Wald, 1902. Lewis Orchard Collection Ref.9180, courtesy of Surrey History Centre.

1. Smyth is the only woman composer to date to have presented an opera at The Met. The performances of her second opera, Der Wald (The Forest), on 11 and 20 March 1903 yield the only instance out of over 300 different works given at The Metropolitan Opera, New York City between October 1883 and July 2013 to have been composed by a woman. According to one contemporary account, the opera was attended by “one of the largest and most brilliant audiences” of the season, eliciting applause that “continued for ten or fifteen minutes, surpassing even the most generous for which the opera patrons are distinguished.”

2. Smyth withdrew one of her operas during its performance run in a move she believed to be “unique in the annals of Operatic History.” For the première of her third opera, Standrecht (The Wreckers), at the Neues Theater, Leipzig in November 1906, she stipulated that no revisions to the score should be made without her consent. However, she discovered the day before the dress rehearsal that Act III had been extensively cut, and her pleas for reinstatement of the excised material were in vain. In response, following the first performance she removed all of her music from the orchestra pit and took it to Prague, where the opera had already been accepted for performance — though this turned out to be a woefully under-rehearsed fiasco.

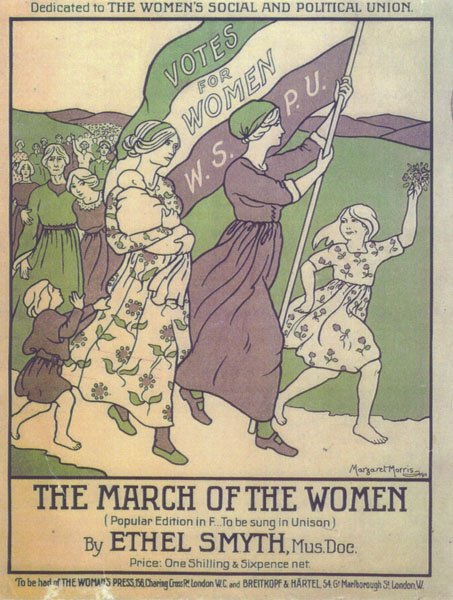

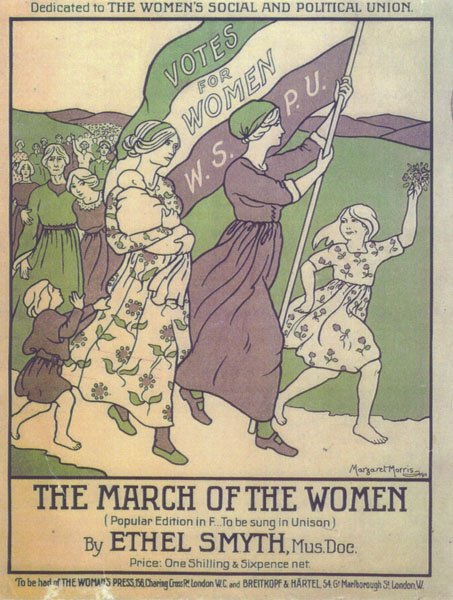

3. Smyth became a leading suffragette in the early 1910s. In September 1910 she met, and became enchanted by, Emmeline Pankhurst. She pledged to devote two years of her life to the women’s suffrage campaign, and a close friendship developed between the two women (Woolf even believed they had been lovers). Smyth’s work for the “Votes for Women” movement is reflected in much of the music she composed at that time, not least The March of the Women, which came to be adopted as the suffragette anthem. She was said to have once stormed into 10 Downing Street and hammered out the March on Prime Minister Asquith’s piano while the Cabinet was in session.

Image: Lewis Orchard Collection Ref.9180, courtesy of Surrey History Centre

4. Smyth served a jail sentence for her suffrage activity. She was one of some 200 women arrested on 4 March 1912 as a result of a co-ordinated window-smashing campaign across the West End of London, and was sentenced to two months in Holloway Prison. Smyth had chosen to target the Berkeley Square home of the colonial secretary, Lewis Harcourt, in retaliation for a remark he had made along the lines that “if all women were as pretty and as wise as his own wife, [they] should have the vote tomorrow.” She recounted the episode on the BBC National Programme in 1937, in interview with the author Vera Brittain.

5. Smyth kept a series of dogs for over fifty years. Her first dog, given to her in 1888, was a St Bernard cross called Marco, who travelled everywhere with her. In 1901, a friend presented her with an Old English sheepdog puppy she named Pan, who became the first in the line of sheepdogs she successively numbered Pan II, Pan III, up to Pan VII. Her lesser-known book Inordinate (?) Affection: A Story for Dog Lovers (1936), a collected biography of some of her canine companions, stands alongside such classics as Virginia Woolf’s Flush and Jack London’s The Call of the Wild as famous examples of dogs in literature.

Christopher Wiley is Senior Lecturer in Music at the University of Surrey, UK. His research primarily examines musical biography and the intersections between music and literature. Other interests include music and gender studies, popular music studies, and music for television. He is author of “Music and Literature: Ethel Smyth, Virginia Woolf, and ‘The First Woman to Write an Opera’” published in The Musical Quarterly. Follow Christopher Wiley on Twitter. Read his blog. He can also be found on Scoop.it!.

The Musical Quarterly, founded in 1915 by Oscar Sonneck, has long been cited as the premier scholarly musical journal in the United States. Over the years it has published the writings of many important composers and musicologists, including Aaron Copland, Arnold Schoenberg, Marc Blitzstein, Henry Cowell, and Camille Saint-Saens. The journal focuses on the merging areas in scholarship where much of the challenging new work in the study of music is being produced.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only music articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Five facts about Dame Ethel Smyth appeared first on OUPblog.