Guest post by T Campbell.

Can the soul of Western civilization be found in a pair of red briefs? Was our first great superhero at his strongest, his noblest, his superest, before modern interpretations stripped him of his underwear? Is there a connection?

A generation ago, when those red briefs were an inseparable part of Superman’s design, he was the most familiar superhero by a wide margin, leading the field in film adaptations,[1] headlining cartoon shows,[2] and even winning over famous media critics who were fiction writers in their own right. Even now, if you believe superheroes have anything to say to American culture or the human experience, you sort of have to start with him, because he’s the prototype.

Umberto Eco called him “the representative of all his similars” [3] and Harlan Ellison described him as one of “only five fictional creations known to every man, woman, and child on the planet.”[4] Born in the early hours of a visual, easily reproduced medium, he was popular enough to codify most of what being a superhero meant. The Oxford English Dictionary even mentions him by name in its definition of “superhero”:

su·per·he·ro ˈso͞opərˌhirō noun: superhero; plural noun: superheroes; noun: super-hero; plural noun: super-heroes. a benevolent fictional character with superhuman powers, such as Superman.[5]

And yet, Batman emerged a year later with no superhuman powers at all, and he was far from the only superhero to flout that membership requirement.[6] What really seemed to make a superhero a superhero, in the minds of the public, was the benevolence, the codename and the costume.

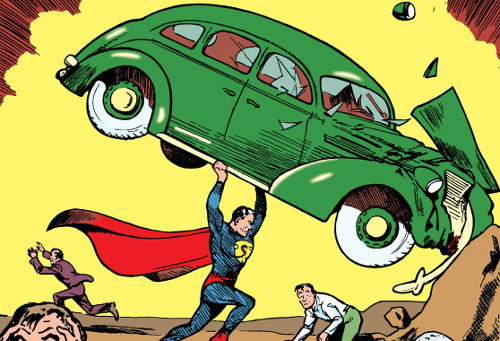

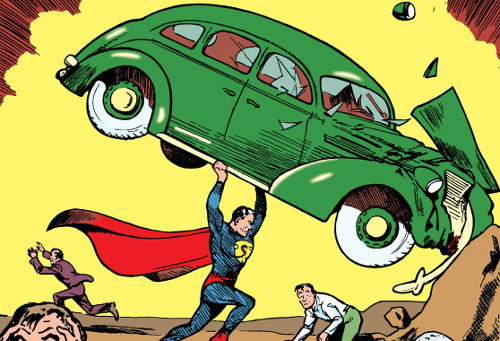

Superman is a strong man created by weak boys. Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster were nerdy teens when they came up with their first “Superman,” a madman with mental, not physical, powers.[7] Their second draft, far closer to the version we know, had what appeared to be a streak of white in his hair and a bare chest.[8] And those trunks, which persisted through other versions for eighty years.

Lacking any personal experience being strong, S. & S. took Superman’s powers from their beloved science fiction, and his costume from the circus.[9]

Underpants on tights were signifiers of extra-masculine strength and endurance in 1938. The cape, showman-like boots, belt and skintight spandex were all derived from circus outfits and helped to emphasize the performative, even freak-show-esque, aspect of Superman’s adventures. Lifting bridges, stopping trains with his bare hands, wrestling elephants: these were superstrongman feats that benefited from the carnival flair implied by skintight spandex. Shuster had dressed the first superhero as his culture’s most prominent exemplar of the strongman ideal, unwittingly setting him up as the butt of ten thousand jokes.

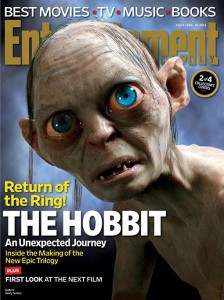

Grant Morrison [10]

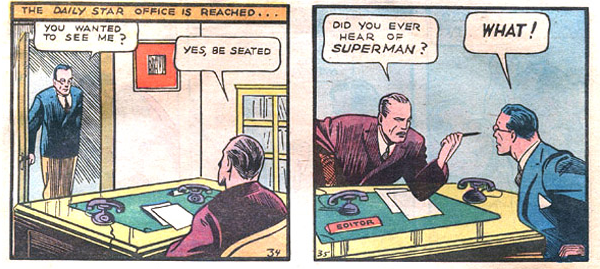

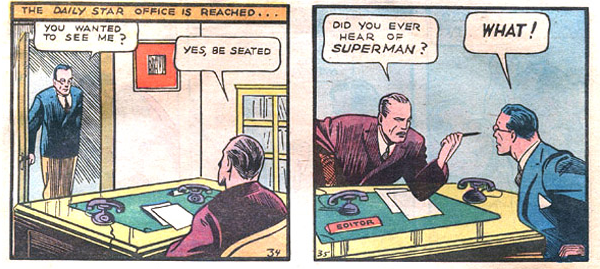

Actually, Siegel and Shuster thought of Superman’s other clothes as the mockable ones. To fully understand the significance of Superman’s costume, look at him when he’s out of it—when he’s Clark Kent.

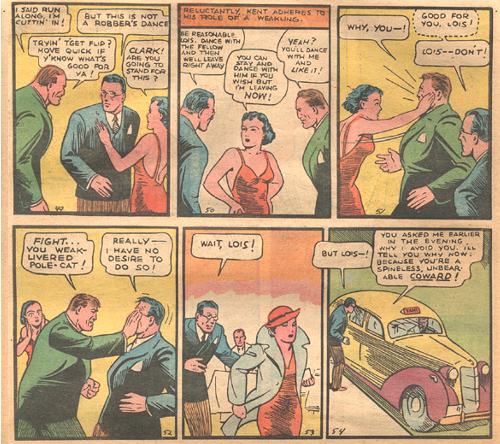

In virtually every version of Superman, Clark is an exercise in patient self-restraint, the ultimate man pretending day by day to be the ultimate common man. In his early days, this restraint was a superstrongman feat all its own, because Clark was extra pathetic—the better for Siegel, Shuster and the readers to identify with him.

I had crushes on several attractive girls who either didn’t know I existed or didn’t care I existed. So it occurred to me: What if I was really terrific? What if I had something special going for me, like jumping over buildings or throwing cars around or something like that?

Jerry Siegel [11]

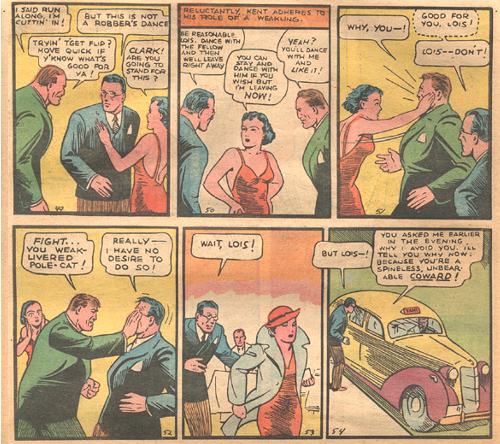

Kent looked like Shuster, who later lifted weights for five years but never developed the bodybuilder’s confidence.[12] If Kent’s daily humiliations echoed Siegel’s past, they also predicted part of Shuster’s future.[13] When Shuster’s worsening eyesight drove him out of cartooning, he went back to deliveries, showing up at his former publisher carrying a package and wearing a ratty, worn-out suit.[14]

It’s not hard to imagine nerdy Shuster stammering “Sign here, please” in the same voice that Kent used to ask Lois, on their first date, if it wouldn’t be “reasonable” to let a bullying gangster have just one dance with her.[15]

Yet Shuster also drew Clark with a rock-hard physique that threatened to burst out of his jacket and pants at any moment. Every so often, after meekly tolerating an editor’s blustering or Lois’ icy contempt, “Clark” would crack a smile: if only they knew. For him, the angst Siegel and Shuster had felt in real life was just a pose, a suit he put on sometimes. And then he’d hear someone in trouble and strip off his shirt to reveal the S-shield underneath. The red trunks would soon follow. Underwear, for the underself.[16]

It was all just a game. Everything was going to be all right. Superman cheerfully presided over a world of bright rainbow colors where hurts and humiliations were temporary. Indeed, after a couple of years he developed a code against killing—a code most superheroes also followed.[17]

They also imitated the briefs, especially his most immediate peers—the original versions of Batman, Robin, Hawkman, Hourman, Starman, Dr. Fate, the Spectre, the Atom, and the Star-Spangled Kid all rocked the look as seen below. [18] And yes, more than half of those heroes also followed his “Somethingman” naming convention.

The 1960s and 1970s still saw plenty of new trunks-wearers among Avengers like Giant-Man and the Vision, mutants like Magneto, and gods like Orion. The Thing wore only trunks, and the Hulk torn purple pants. Other gods and mutants (Thor, Darkseid, the early X-Men) wore onesies broken up with a belt.[19] Strangely, two X-Men who each disdained the other’s sense of style—Cyclops and Wolverine—went full trunks-over-pants from the 1970s into the 1990s.[20]

This tendency to assign the look to gods and mutants, though, instead of more central figures like Captain America, Mister Fantastic, and Spider-Man, may have been an early sign that it was on its way out. These newer Marvel characters stood out from the first generation by being more fully realized people in their civilian identities, if not eliminating the dual identity altogether. Of the marquee Marvel heroes, only Thor, whose fashions and godly nature made him the exception that proved the rule, was introduced with a Clark Kentish self-denying secret identity.[21]

Superman’s influence continued to erode as the decades wore on. Newer heroes showed less interest in the code against killing or in names ending in “-man.”[22] And costume redesigns left the trunks behind. The X-Men got into black leather for a while, and their later, more colorful costumes still left the briefs out.[23]

Tim Burton’s 1989 Batman film “de-briefed” comics’ second most famous underwear wearer. Batman never went back to the briefs in any succeeding movies: they began to fade from the comics as well, as shown in this sample of Ben Moore’s larger survey of Bat-suits seen in various media, covering the period from 2005-2012.[24]

The look could still show up in the deliberately retro stylings of a film like The Incredibles; despite fashionista Edna Mode’s disdain for capes and insistence that “I never look back, darling, it distracts from the now,” her creations had an old-fashioned flair that matched the traditional values of their wearers, the kind of nuclear family that seemed to headline most sitcoms from the 1950s to the 1980s.[25]

Superman, for many years, seemed content to be a bit old-fashioned. His brand hadn’t been about “cool” for a long time: it was more about safety and stability. The comic-book Superman of 1962 or 1988 was more scientist than slugger, often approaching problems from a cool remove. His peers honored him as the one who came first, and therefore someone who didn’t need to follow the trends. He had, after all, defined them.[26]

Nevertheless, as superheroes and popular entertainment in general grew increasingly impatient with the “no kill rule,” the temptation to challenge Superman for wearing last year’s morals was overwhelming. The movies of the 1970s and 1980s danced around the issue by making Superman’s foes inanimate[27] or leaving their fates uncertain.[28] But many of his best-loved adventures, the ones that could claim to influence his canon, saw him sorely tempted to end a life—or even saw him succumb.

However, this was always an ending for the character as we knew him, as proved by what came next. In one such story, Superman instantly punished himself by giving up his super-powers and retiring.[29] In another, he died along with his foe.[30] In a third, he had a mental breakdown and went on a long journey of soul-searching before returning to duty with an even firmer vow, “Never again.”[31] In multiple stories of a world not our own, a world gone wrong, Superman deciding to kill is his first step toward villainy.[32] And at least once, he used magicians’ stage tricks to fool the world into thinking he’d broken his rule—just to show how terrible a Superman unchecked by restraint would be.[33]

The conservatism is unmistakable but charming. Nearly all fictional franchises create a moral universe that rewards readers for following them, and Superman is no exception. However much he struggled with it, refusing to kill would always be The Right Choice. Other heroes would always look to him for guidance, saluting his cape as if it were the flag. Underwear on the outside of your pants totally works.

The super-briefs stayed on for generations, in comics, movies, TV, Halloween costumes and branded, official kids’ underwear—an incentive to finish toilet training if ever there was one. [34]

And then everyone seemed to reject them at once. In 2011, Jim Lee redesigned all DC Comics’ top-selling characters, giving them the scratchy, slightly self-conscious “edginess” that had made Lee famous.[35] But the artist who had kept Cyclops and Wolverine in trunks now broke precedent. The red of Superman’s trunks shifted to his belt, and its buckle took a shape echoing the chest symbol. The trunks vanished.

I think you have to go for the core elements that are critical to the costume and freely change what looks dated… For me, the red trunks on Superman, you didn’t notice. It gets colored in blue anyhow.[36]

In the same year’s Action Comics, Grant Morrison and Rags Morales emphasized the populist strain in Siegel’s early, Depression-era stories. Theirs was a Superman for the 99 percent, and his costume was the believable result of a reporter’s salary: a screen-printed T-shirt, short cape, and jeans. [37] Morrison explained:

We felt it was time for the big adventures of a 21st-century Paul Bunyan who fights for the weak and downtrodden against bullies of all kinds, from robot invaders and crime lords to corrupt city officials. The new look reflects his status as a street-level defender of the ordinary man and woman.[38]

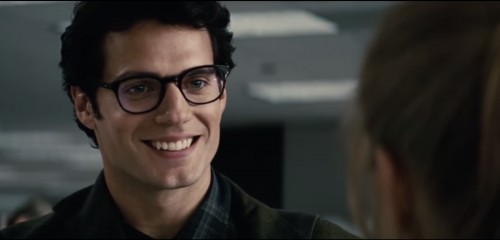

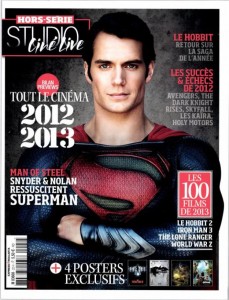

The filmmakers of 2013’s Man of Steel found the trunks clashed with their concept of the costume as alien armor. Even director Zack Snyder, whose adaptation of Watchmen had featured two trunks-over-pants designs to the comic books’ one,[39] now found himself breaking precedent.

The costume was a big deal for me, and we played around for a long time. I tried like crazy to keep the red briefs on him. Everyone else said, “You can’t have the briefs on him.” I looked at probably 1,500 versions of the costumes with the briefs on.[40]

Who stole Superman’s undies? Morrison takes responsibility for his part in it, Lee shrugs about careless colorists and readers, Snyder bows to the input of unnamed advisors. Their earlier output, though, suggests they had no dislike for the design, just a need to follow popular taste rather than acting as if Superman still shaped it. But fashion, as ever, sends a message about its wearer.

In Man of Steel, the blue is navy, the yellow rusty and gritty. Smallville’s Clark operates without a costume at all. Both versions of Superman are painfully unsure of themselves, closeted, desperate, and far less successful than earlier versions at preventing collateral damage.[41] Smallville averaged one death per episode in each season.[42] Superman’s first TV outing, The Adventures of Superman, averaged none—and lasted six seasons to Smallville’s ten.[43]

Analyst Charles Watson puts the Man of Steel death toll at 129,000, with the last of those deaths by Superman’s own hand.[44] Contrast this with Superman: the Movie, in which Superman saves everyone at risk from a devastating earthquake except Lois Lane, whom he then rescues via time travel. Man of Steel opened in eight times as many theaters as Superman: The Movie.[45] An influential new beginning, and by his old standards, an inauspicious one.

Man of Steel Superman may scream in anguish after killing General Zod, but unlike in the other stories where he crosses that line, he seems to get over it pretty fast. One scene later, he’s cheerfully knocking an Army drone out of the sky. He actually seems more relaxed and happy after the killing is done! No doubt Lois’ approval helps, but even so.

Man of Steel screenwriter David Goyer appears to be weaving some acknowledgments of that issue into its sequel.[46] He would like to assure you that the Superman you remember from your childhoods isn’t gone—he’s just not fully reborn yet.

Our movie was, in a way, Superman Begins; he’s not really Superman until the end of the film. We wanted him to have had that experience of having taken a life and carry that through onto the next films. Because he’s Superman and because people idolize him, he will have to hold himself to a higher standard.[47]

It’s true that Smallville and Man of Steel focus on a young Superman who hasn’t had a chance to become the graceful legend of earlier works. But these have been the portrayals to reach the widest audience in the last decade. [48] Even in current comics, though they have a lighter color scheme and mood, he’s an impulsive younger man with a quick temper.[49] The latest Superman project to be announced, TV’s Krypton, will take place thirty years before his birth.[50]

Put it all together and you’re left with the impression that Superman’s 21st-century caretakers would rather invoke the smiling, life-preserving, cool-headed circus superstrongman than actually show him. Will the next film change that? Will it give him the power and certitude to preserve all intelligent life in his path with a calm soul and a wink at the viewer? Or is that Superman no longer filmable, a relic to be tossed out like a pair of outgrown briefs?

Tights may tell.

[1] 1978’s Superman: The Movie earned nearly six times its budget and spearheaded the only superhero film franchise of the following decade.

[2] Some variation of Super Friends, always with Superman as the headliner, appeared on TV from 1973-1986.

[3] Eco and Natalie Chilton. “The Myth of Superman. The Amazing Adventures of Superman. Review.” Diacritics, 2(1), pp. 14-22. Spring 1972.

[4] Ellison, Foreword to Dennis Dooley and Gary Engle, Superman at 50: The Persistence of a Legend, 1987.

[5] Oxford English Dictionary entry, 2014. Found via Google search, November 22, 2014.

[6] Batman later used gadgets as sort of substitute super-powers, but other figures—the first Atom, Wildcat, and the Spirit, among others—used nothing but ordinary fists.

[7] Jerry Siegel (illustration by Joe Shuster), “The Reign of the Superman,” Science Fiction: The Advance Guard of Future Civilization #3, 1933.

[8] Les Daniels, Superman: The Complete History, 2004, p. 17.

[9] Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, Action Comics #1, 1938.

[10] Grant Morrison, Super Gods: What Masked Vigilantes, Miraculous Mutants and a Sun God from Smallville Can Teach Us About Being Human, 2012.

[11] Gerard Jones, Men of Tomorrow: Geeks, Gangsters and the Birth of the American Comic Book, 2005, p. 63.

[12] Tom Andrae with Geoffrey Blum and Gary Coddington, “The Birth of Superman,” Nemo #2, 1983.

[13] Craig Yoe, Secret Identity: The Fetish Art of Superman’s Co-creator Joe Shuster, 2009; Brad Ricca, Super Boys: The Amazing Adventures of Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster—The Creators of Superman, 2013.

[14] Joe Simon, My Life in Comics, p. 188, 2011.

[15] Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, Action Comics #1, 1938.

[16] Alex Ross for Alex Ross and Paul Dini, Superman: Peace on Earth, p. 7, 1938.

[17] Editor Whitney Ellsworth was the driving force behind this rule, as early as 1940, years before the Comics Code Authority.

[18] Art by Jerry Ordway, Who’s Who in the DC Universe #12, 1986.

[19] Tim Leong, “A Venn Diagram of Superhero Tropes,” Super Graphic: A Visual Guide to the Comic Book Universe, 2013.

[20] Art by Jim Lee for X-Men #11, 1992.

[21] Dr. Donald Blake is more complicated than we can cover here,

[22] Wikipedia’s “List of notable superhero debuts” shows a tapering off of such names after the 1960s.

[23] Grant Morrison and Frank Quitely, New X-Men #114, 2001; Joss Whedon and John Cassaday, Astonishing X-Men #1, 2004.

[24] Selected from Ben Moore’s 2012 “Batman Infographic: Every Significant Bat-Suit Ever,” found at Screen Rant, http://screenrant.com/batman-infographic-every-batsuit-benm-144238/.

[25] Brad Bird, The Incredibles, 2004.

[26] Image by Jim Lee for DC Comics.

[27] In Superman: The Movie and Superman Returns, natural disasters are the chief problem; in Superman III and IV, the main villains are destroyed but arguably not truly alive.

[28] Superman II.

[29] Alan Moore, Curt Swan and Kurt Schaffenberger, Action Comics #583, 1986. Source of the image below and the last “Silver Age” Superman story.

[30] Dan Jurgens, Superman #75, 1992. The famous, notorious “Death of Superman.”

[31] John Byrne, Superman #22, 1988; Jerry Ordway, Adventures of Superman #450, 1989; Roger Stern and Kerry Gammill, Superman #28, 1989; George Perez, Action Comics #649, 1989. John Byrne’s last Superman story, and a heavy influence on Man of Steel in terms of who Superman kills and why.

[32] Central premise of the video game Injustice: Gods Among Us, released in 2013, ongoing storyline in the Justice League/Justice League Unlimited animated series (2001-2006) and invoked in the climax of 1996’s Kingdom Come by Mark Waid and Alex Ross.

[33] Joe Kelly and Doug Mahnke, Action Comics #775, 2001. Adapted into a 2012 direct-to-DVD animated film, Superman vs. The Elite.

[34] Photo from http://savinginsalinas.blogspot.com/2011/09/yard-sale-finds.html. Superman has had many adaptations but this was true of virtually all of them until 2011.

[35] Geoff Johns and Jim Lee, Justice League #1, 2011 (image source), and George Perez, Superman #1, 2011. Lee’s career goes back to 1987.

[36] WonderCon 2013 panel, “WC13: Jim Lee Talks DC, Answers Fan Questions and More!,” Comic Book Resources, March 30, 2013, http://www.comicbookresources.com/?page=article&id=44604.

[37] Grant Morrison and Rags Morales, Action Comics #2, 2011.

[38] Dareh Gregorian, “Bird? Plane? Superdude!,” The New York Post, July 18, 2011.

[39] Nite Owl wore them in both versions, but Ozymandias picked them up in the movie. Comics 1986-1987, film 2009.

[40] Reed Tucker, “‘Steel’ this movie,” The New York Post, November 25, 2012. Image from Man of Steel, 2013.

[41] In addition to the film itself, see Emma Dibdin, “‘Man of Steel’: Zack Snyder defends Superman’s ‘collateral damage,’” Digital Spy, August 30, 2013.

[42] According to smallville.wikia.com. In some seasons it was as high as three.

[43] 1952-1958; 2001-2011.

[44] Graphic by Chris Ritter, “The Insane Destruction That the Final ‘Man Of Steel’ Battle Would Do To NYC, By The Numbers,” Buzzfeed, http://www.buzzfeed.com/jordanzakarin/man-of-steel-destruction-death-analysis, June 17, 2013.

[45] Box Office Mojo. http://boxofficemojo.com.

[46] Devin Faraci. “Find Out Superman’s Situation In BATMAN V SUPERMAN,” Badass Digest, December 15, 2014.

[47] 2013 speech at the BAFTA and BFI Screenwriters’ Lecture series.

[48] 2006’s Superman Returns was far less profitable and problematic in a different way.

[49] Johns, Lee, and Morrison have confirmed this is deliberate.

[50] Lesley Golberg, “Syfy, David Goyer Developing Superman Origin Story ‘Krypton,’” The Hollywood Reporter, December 8, 2014.

The biggest success for comics over the past five years hasn’t actually been comics at all: it’s been the movie industry. Superhero films are gigantically big business now, with The Avengers pulling in over a billion dollars worldwide, and the industry paying top-dollar for any new comic rights they can get their hands on. At the same time, superhero films are in a very good critical position as well - Christopher Nolan’s Batman trilogy won Oscars! Top directors are almost literally battling for the chance to get their hands on characters like Daredevil or Luke Cage.

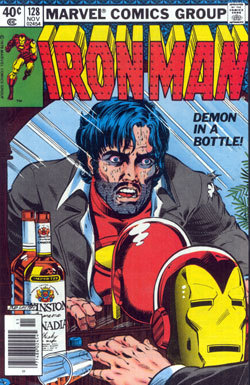

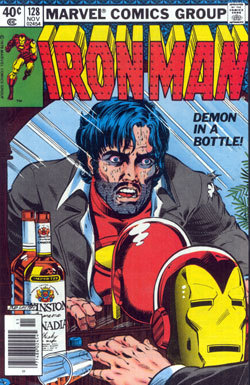

While movies have taken the characters and distilled them into their most winning core – the comic book version of Iron Man was essentially revitalised by Robert Downey Jr’s energetic portrayal of Tony Stark – the comics themselves have struggled to keep up that mindset. Whilst the Iron Man of the movies was flying about, smashing racecars and saving the world, his comic book counterpart was busy being a fugitive, living a miserable life as he attempted to clear his name. The X-Men in X-Men First Class may have been enjoying themselves, but the X-Men in the comics were hounded, segregated on an island and blocked from society. In terms of tone? Mainstream superhero comics have been downbeat rather than optimistic.

Take any comic book version of a character and compare them to the film version. Hal Jordan is nominally dead right now in the DC Universe, but in the films he was Ryan Reynolds! Even Professor X, who is lovely Patrick Stewart and James MacAvoy in the films, has spent the last decade at Marvel being a terrible bastard. And, y’know, dead. For all that the movies may offer superheroes as a safety net for people wanting to be inspired, comics have been offering superheroes as corrupted, agonised people. Now, this isn’t bad storytelling – it’s always been the way. Drama requires a little tragedy from time to time, and comics have had a long time to dwell on their characters. Eventually you run out of ways to move a character, so things have to take a turn for the darker.

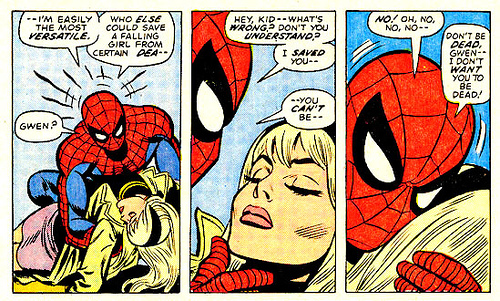

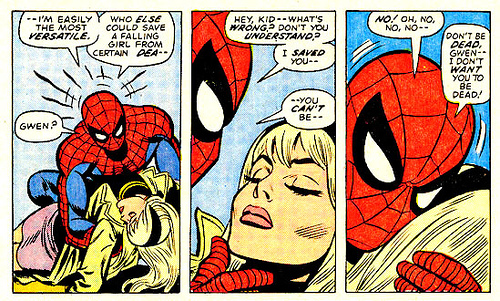

And that’s why it’s going to be so fascinating, two years from now, to sit in a cinema. Because two years from now, Gwen Stacy will die.

Whoa! Spoiler. True, though. The relaunched Amazing Spider-Man trilogy are setting us up for some major tragedy just around the corner. They’ve hired an actor to play Green Goblin, they’re bringing in a Mary Jane, and thematically the first film made it blatant that Gwen has to die for the narrative to be complete. The first film hammered the point that Peter Parker is dangerous for Gwen Stacy, and his decision not to end their relationship (which seemed sweet at the time) is going to look very ominous in two years time.

The other films coming up aren’t going to be much different. If Kick-Ass 2 remains true to the original comic, then fans are going to line up for a horrible rape sequence midway through their movie, followed by a lot of murder and horror. The Man of Steel has been marketed as a brooding, mournful take on the most iconic superhero of all time, while the Wolverine franchise is soon going to introduce doomed love interest Mariko Yashida. And if this wasn’t enough, the next X-Men movie will take us into the Days of Future Past dystopia.

In essence, the movies are going to hit unsuspecting audiences with a wall of ‘darker and edgier’ storytelling all at the same time. Comic book fans have been experiencing this for a while now, with formerly silly characters getting brought back, made miserable, killed off, tortured, or turned evil. The only notable upbeat characters of the last few years have been, perhaps, Stephanie Brown, Pixie, and Squirrel Girl. For the most part, comics have moved their attention towards an older audience, with more mature stories – well told stories, but stories which focus on human drama and horror rather than fantasy and idealism.

Film fans have no idea what they’re going to get into. While comic fans are aware that Gwen Stacy is doomed, the majority of film fans have no idea what’s coming up. It’s going to be MASSIVELY shocking for to see her die. People were prepared to see Uncle Ben die, because it’s what he always does – but adorable Emma Stone? Killed off halfway through a blockbuster trilogy? Film audiences expect superhero films – with a few exceptions – to be comforting, safe, and for all-ages. That’s a big twist for them.

What they’re going to get over the next few years are an unexpectedly brutal series of events, which could completely sour the idea of superheroes as comfort food. Comic fans accepted the move away from all-ages stories – how will film fans react? And Spider-Man is barely going to scratch the surface - are we eventually going to have to deal with Iron Man’s alcoholism? To what extent might that Ant Man film deal with Hank Pym’s history of domestic abuse? Is Channing Tatum still going to die in GI Joe 2?

The reaction of film fans to these next two years of superhero films will determine the future of comic book stories, I think. The reaction people have to this upcoming ‘darker and edgier’ period of films could have massive implications for comic companies. There’s a perception in general that comic books are fun entertainment for kids – but if movies now subject audiences to an onslaught of rape, murder, abuse and horror, what will that do for the next generation of comic fans? If the films are rejected by the public, will that mean the superhero genre of cinema will fall out of favour?

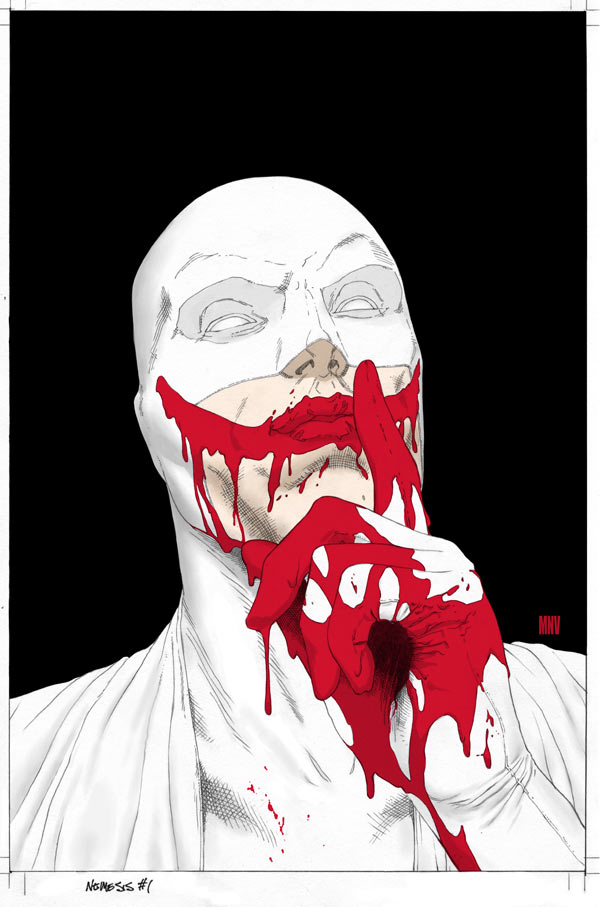

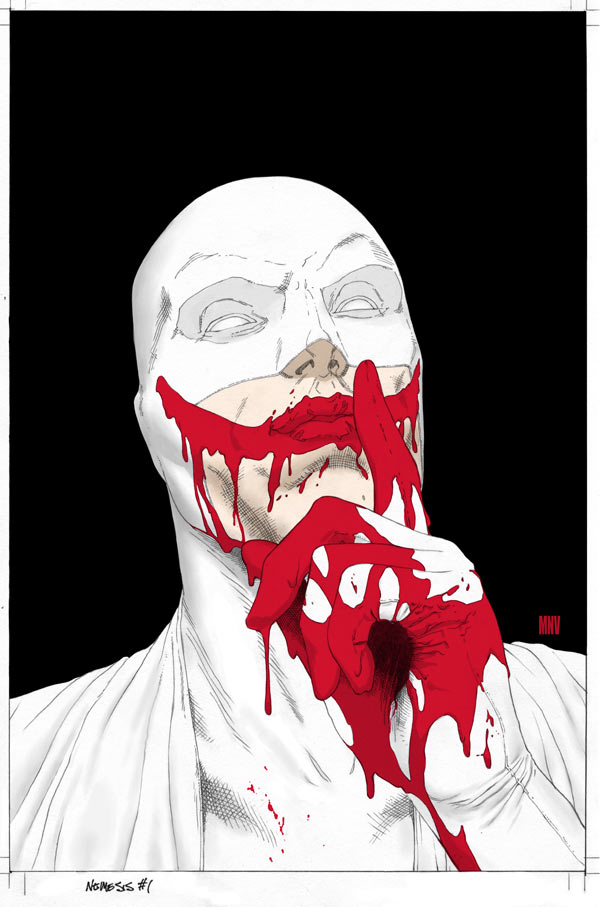

Films tentatively suggested for future release include a Lobo movie, Ant Man, and several Mark Millar projects such as Nemesis and Wanted 2. It’s interesting, isn’t it? There’s little hope for a Wonder Woman or Black Panther film, and yet film companies think audiences can support super-violent, misogynistic works. Films aimed not at all fans, but a smaller, older demographic. Just like happened in mainstream superhero comics! Rather than films suggesting a brighter future for comics, could their turn towards darker and edgier stories actually be the thing which helps to bury the medium entirely?

Steve Morris writes, tweets, and comics. Follow his epic journey!

.jpg)

Now if they could only find a way to put some red shorts on him.

I personally liked the color choices in the original much better. There’s not much thought put in the re-colored version. Check out the savanah scene where superman is flying for an example. I like the original subtle palette in Man of Steel, It kinda has this naturalism and Norman Rockwell look that not a lot of superhero movies have. In a way, It actually harkens back to the nice color palette in the Chris Reeve Superman movies.

I increasingly find myself twiddling with the colour settings of the Mac we play DVDs on… Either to brighten overly dark films or to punch up colours. I’m getting particularly fed up with teal & orange tinted films, and try to drag the colours away to a more natural palette. In case that fails, I’ve opted to watch movies in black & white (which adds a touch of class to the tripest tripe).

We’ll get out the Superman DVD to see whether we can replicate the restored colour effect.

If only NeoConservative ideology could be removed from Snyder’s movies with similar ease.

I guess people really hate Man of Steel that much. VideoLab just makes up stuff to make it look bad; but the worst part? Everybody jumps on the hate bandwagon.

http://furiousfanboys.com/2015/04/viral-video-lies-about-how-man-of-steel-really-looks/