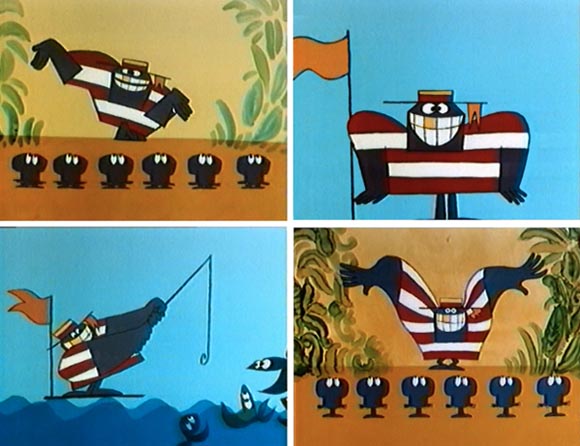

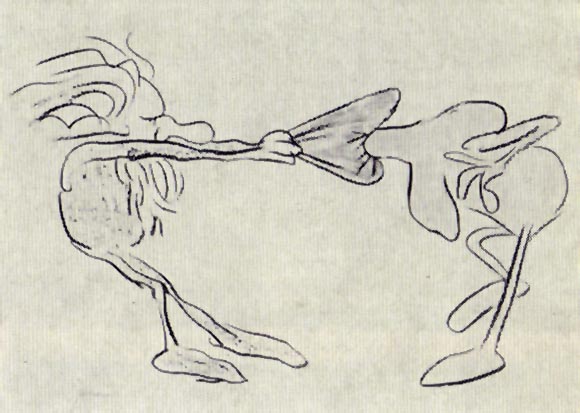

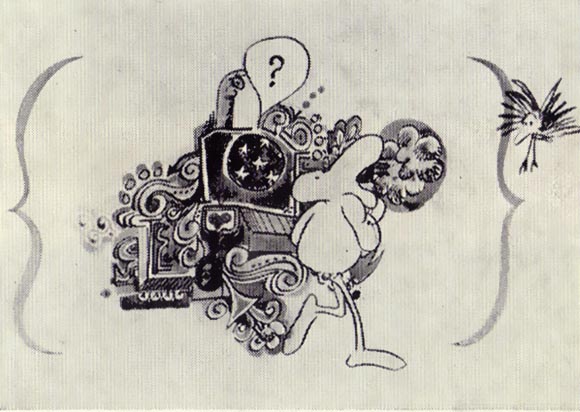

I’ve wanted to watch Errol Le Cain’s Sailor and the Devil ever since I saw these stills on Hans Bacher’s website a few years ago. Animation research Garrett Gilchrist recently unearthed a copy, which although incomplete and poor quality, offers a tantalizing glimpse of this masterful short.

Le Cain made Sailor and the Devil in 1966 while working at Richard Williams’ studio in London. He had been working there for only a year when Williams invited him to direct the film under his supervision. Williams explained the idea behind the project in a documentary: “[Le Cain is] doing everything so he’s getting ten years’ experience in one, and we get a film.”

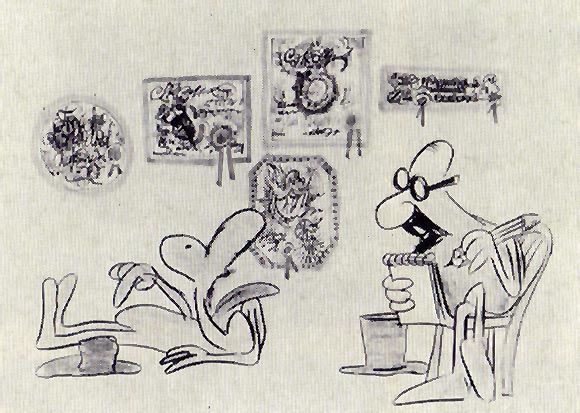

The results are refreshingly original. Le Cain invents an idiosyncratic style of movement that combines jittery bursts of motion with pleasing dance cycles. When the storm arrives in the film or the skeleton wave threatens to overwhelm the sailor, we encounter a world of pure graphic art. Le Cain uses the full range of color, movement, design, and cinematic devices to create an exciting universe that could exist nowhere but in an animated film.

Le Cain made significant contributions to the production design of The Thief and the Cobbler, and afterward became a well known children’s book illustator. He died in 1989 at the age of 47.

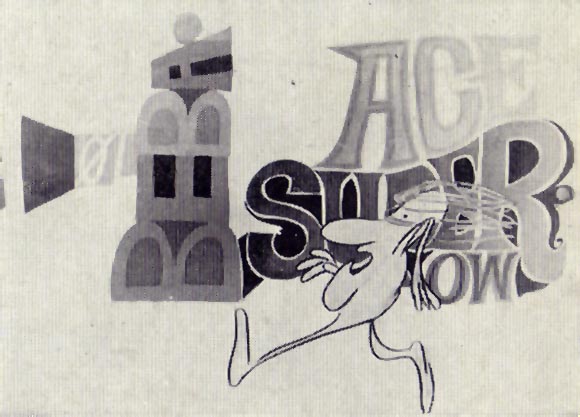

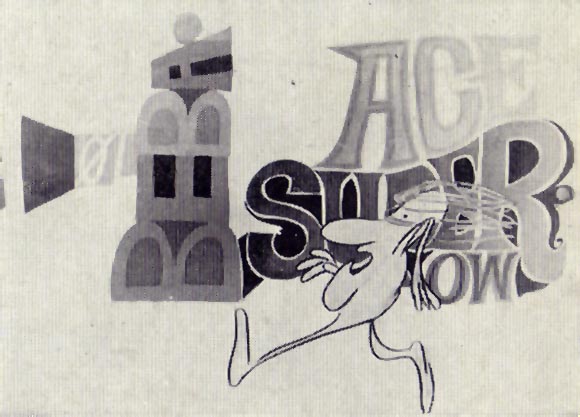

Among the many projects he did with Richard Williams, Le Cain designed these titles for The Liquidator (1965):

There’s a clip of Le Cain and Williams working on Sailor in this documentary from 1966:

(via Michael Sporn)

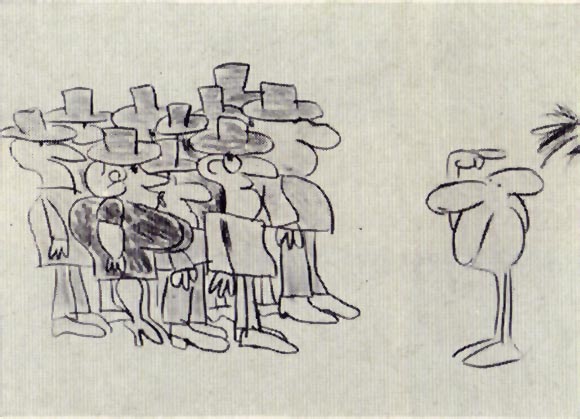

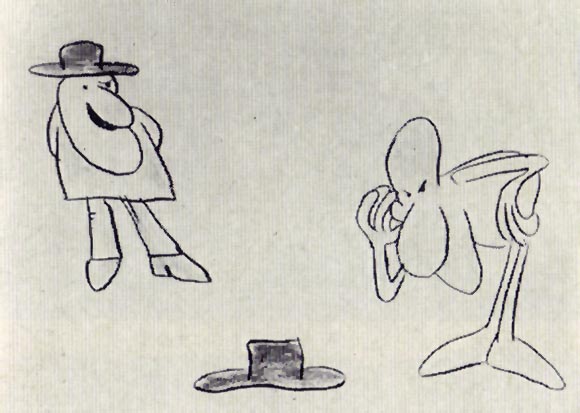

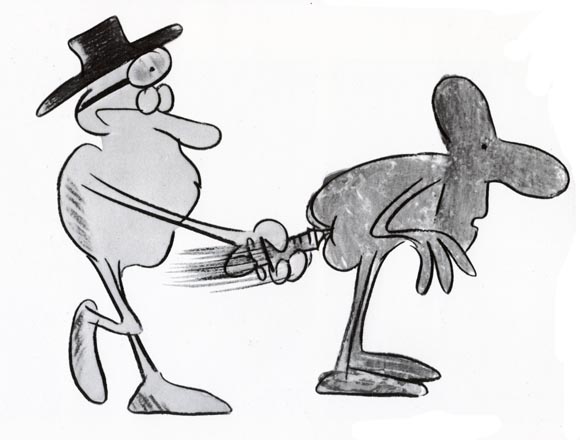

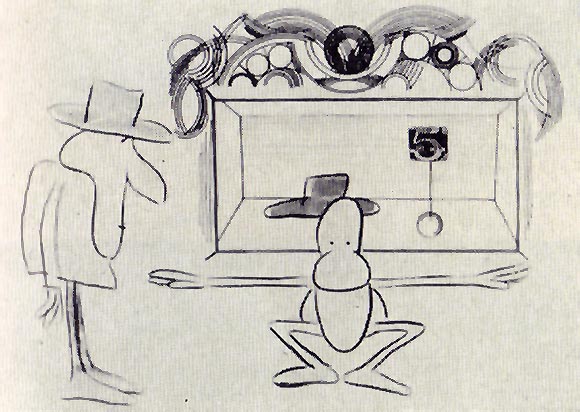

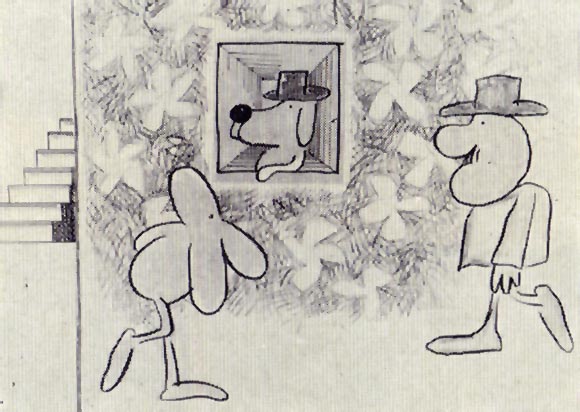

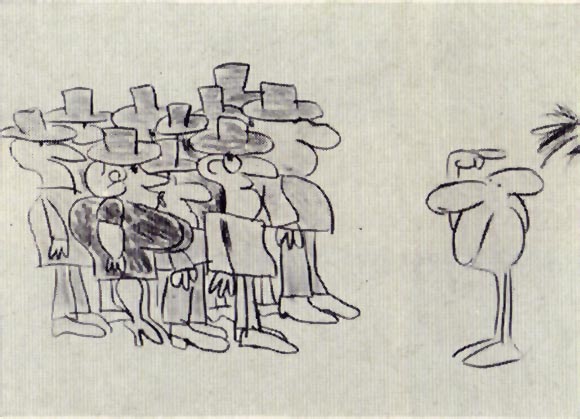

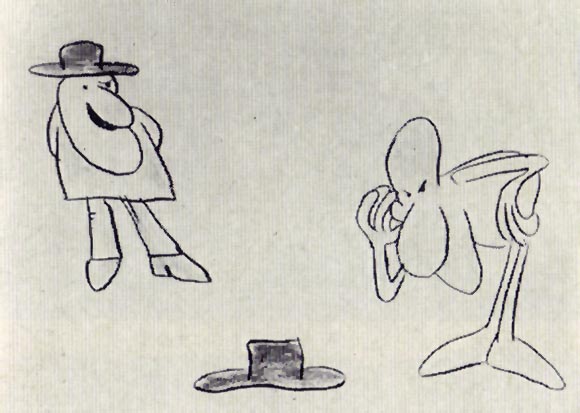

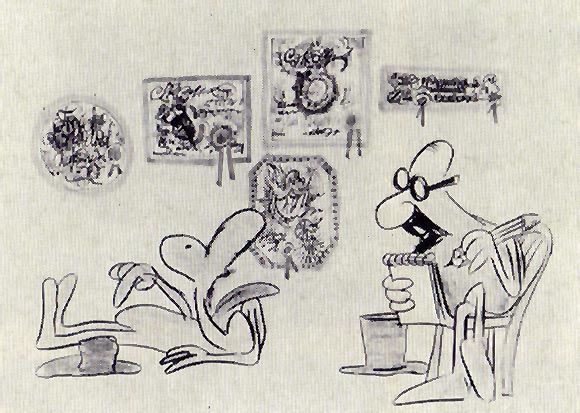

Fans of classic animated shorts are undoubtedly familiar with John and Faith Hubley’s 1964 short The Hat, but there was another short released in the same year that was also called The Hat. This short, El Sombrero (retitled The Hat in English) was one of the few entertainment shorts produced by the Spanish outfit Estudios Moro, which I wrote about yesterday.

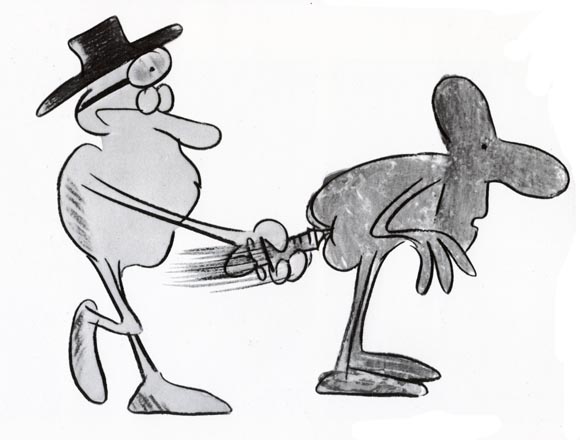

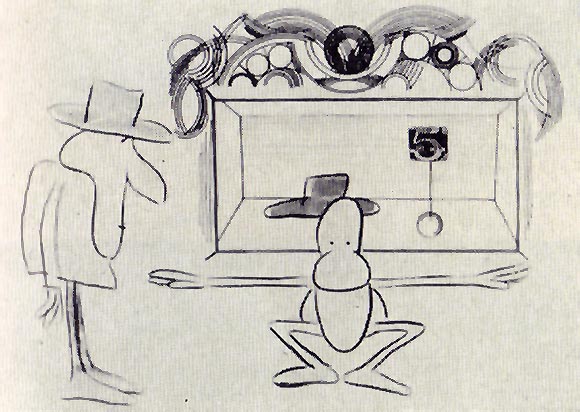

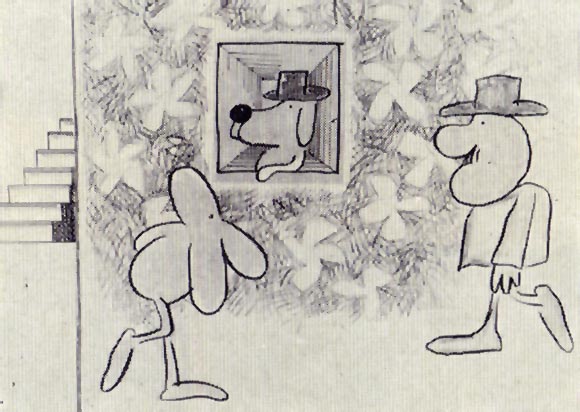

According to the 1967 book Film & TV Graphics, it’s “the story of a social outcast and his troubles with a hat…the hat is here a status symbol, but the hero never masters it, for it happens to be a hat that talks.”

Despite being animated in Spain, the film’s principal artists were all Americans. The director, Bob Balser, who I’m happy to report is still with us, had been floating around European studios in Denmark and Finland before landing at Estudios Moro to make this film. A few years after this short, Balser went to England where he would assume his most high-profile role as the animation director of Yellow Submarine.

The story was written and designed by Alan Shean, who was a fixture of the Fifties animation scene. He had worked for most of the major LA commercial houses and had also been an instrumental artist in the early years of Rocky and Bullwinkle. The background artist on the film, Dean Spille, who just turned 85, also worked on TV commercials, primarily at Playhouse Pictures. Following El Sombrero, he began working with Bill Melendez on the Peanuts specials and features, and became one of Melendez’s key artists for the next 35 years.

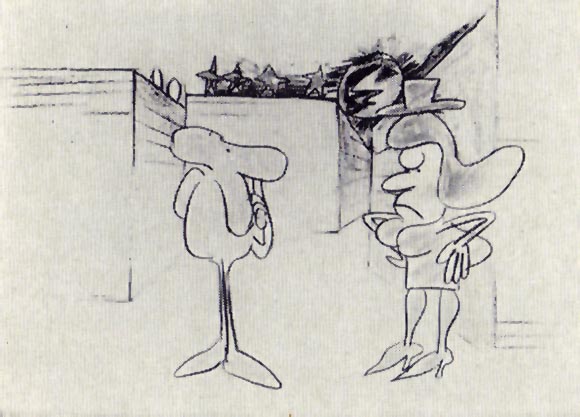

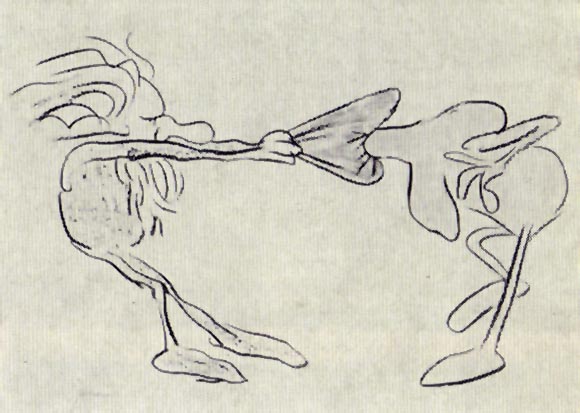

If the overriding trait of Fifties animation was an emphasis on formal design, then the defining element of Sixties animation was the desire to break away from formulaic ways of drawing characters. Shean, like so many other artists of the era, embraced a freer, more illustration-oriented approach to drawing. The poses and expressions in the stills below don’t look like they belong on any traditional model sheet; they are tailor-made to meet the requirements of each scene. The fluid graphic quality of the line is reminiscent of Robert Osborn’s illustrations and there’s a lovely, improvisational feel to the drawings. It would be a real treat to see drawings such as these in motion.

If you’ve seen El Sombrero or have more to share about the film, please comment.

What constitutes a “lost” film? The traditional definition is a film whose existence is confirmed but of which no prints can be found. But in this day and age of infinite abundance on the Internet, there is also another type of lost film. This is the film of which prints readily exist, but the film is rarely screened publicly, unavailable online, and is not part of the general animation community’s discussion.

An even more personal definition of a “lost” film is simply a film that I wish to see and am unable to find. I plan to regularly highlight these films in this new feature called “Lost Films.” It represents a desire to draw attention to the rich history of animated filmmaking and the various ways that artists have explored the medium throughout the years.

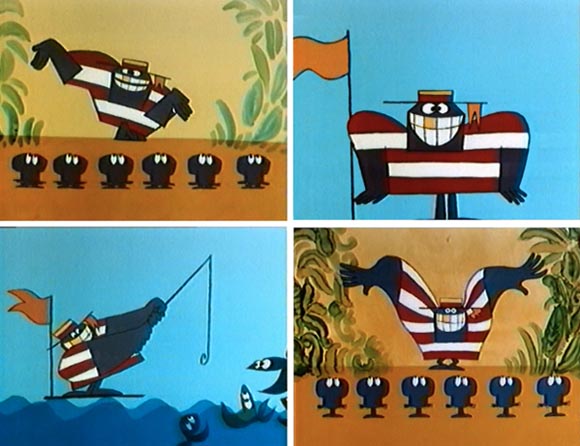

The first “lost film” is Calaveras (Skulls, 1969), a French short directed by Jacques Colombat (b. 1940) and produced by Les films Armorial. Colombat, who was a protégé of the important French animation director Paul Grimault, was inspired by the artwork of Mexican illustrator José Guadalupe Posada to create his Day of the Dead-themed short. Using a combination of cel animation and cut-out, Colombat animated the film with Jean Vimenet and Jean-François Laguionie, the latter of whom recently released the feature Le Tableau.

Colombat appears to still be alive and well. In fact, a photo of him riding a bicycle around Paris randomly ended up on the Associated Press last October.

The film’s running times that I’ve seen vary between 11 and 15 minutes. Here is the most complete synopsis of Calaveras that can be found online:

An unusual and aesthetically interesting cartoon, set in Mexico at the time of the defeat of Maximilian I by the Republican forces under Juárez. It tells the story of an imprisoned Algerian soldier who, having been left behind when Maximilian’s French troops were forced to withdraw, faces a firing squad. While he is in jail he dreams of life outside, but eventually his time comes. According to popular Mexican belief however, men continue their previous lives in the state of skeletons and there is every indication that the soldier will soon find his place in this new world.

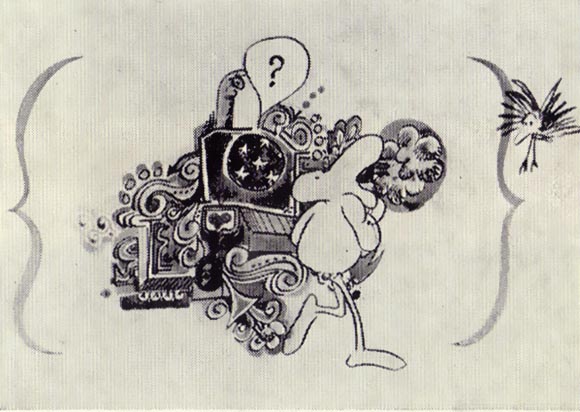

The adventurous design and color of Calaveras excites the senses. I can’t imagine how these drawings are animated as cut-outs—or if they’re even animated—but I’d love to find out.