new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: John Calvin, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 5 of 5

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: John Calvin in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Julia Callaway,

on 12/13/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

Religion,

bible,

Exodus,

Moses,

Christian Bale,

martin luther king jr,

Ridley Scott,

John Calvin,

*Featured,

Reformation,

TV & Film,

Protestantism,

Exodus Gods and Kings,

Deliverance Politics from John Calvin to Martin Luther King Jr.,

Eusebius of Caesarea,

Exodus and Liberation,

John Coffey,

Add a tag

Moses and Pharaoh are returning to the big screen in Ridley Scott’s seasonal blockbuster, Exodus: Gods and Kings. With a $200m budget and Christian Bale in the leading role, the British director will hope to replicate the success of Gladiator (where he resurrected the sword and sandals genre) and surpass the shock and awe of Cecil B. DeMille’s The Ten Commandments. Even before its release, the movie sparked controversy. The casting of white actors as Egyptians provoked charges of racial discrimination; describing Moses as ‘barbaric’ and ‘schizophrenic’ did not endear the leading actor to traditional believers; and casting a truculent young boy as the voice of Yahweh was bound to raise eyebrows. In other respects, the storyline remains traditional. Indeed, the film follows a long tradition of interpretation by presenting the Exodus as a political saga of slavery and liberation. 600,000 slaves are delivered as an oppressive empire is overwhelmed by divine power.

This political reading of the biblical epic will be familiar to anyone who has studied its remarkable reception history. In Christian preaching, liturgy and hymnology, Exodus has been read as spiritual typology — Israel points forward to the Church, Pharaoh’s Egypt to enslavement by Satan, Moses to the Messiah, the Red Sea to salvation, the Wilderness Wanderings to earthly pilgrimage, the Promised Land to heavenly rest.

Yet there has been an almost equally potent tradition of reading Exodus politically. It originated with Eusebius of Caesarea in the fourth century, who hailed the Emperor Constantine as a Mosaic deliverer of the persecuted Church. It took on new intensity when the Protestant Reformation was promoted as liberation from ‘popish bondage’. As a vulnerable minority, European Calvinists identified with the oppressed children of Israel in Egypt and then celebrated national reformations in Britain and the Netherlands as a new exodus. The title page of the Geneva Bible (1560) pictured the Israelites pinned against the Red Sea by the chariots and horsemen of Pharaoh, the moment before their deliverance. Deliverance became a keyword in Anglophone political rhetoric, a term that fused Providence and Liberation.

Over the coming centuries, this Protestant reading of Exodus would go through some surprising twists. The Reformers had sought deliverance from the Papacy, but radical Puritans condemned intolerant Protestant clergy as ‘Egyptian taskmasters’. Rhetoric that had once been trained on ecclesiastical oppression was turned against ‘political slavery’, as revolutionaries in 1649, 1688 and 1776 co-opted biblical narrative. For Oliver Cromwell, Israel’s journey from Egypt through the Wilderness towards Canaan was ‘the only parallel’ to the course of English Revolution. For John Milton, tolerationist and republican, England’s Exodus led to ‘civil and religious liberty’, a phrase coined in Cromwellian England. The most startling development occurred during the American Revolution, when Patriots unleashed the language of slavery and deliverance against ‘the British Pharaoh’, George III. The contradiction between their libertarian rhetoric and American slaveholding galvanized the nascent anti-slavery movement on both sides of the Atlantic. Black Protestants now seized upon Exodus and the language of deliverance. ‘For the first time in history’, writes historian John Saillant, ‘slaves had a book on their side’.

African Americans inhabited the story like no other people before them. When they fled from slavery and segregation and migrated to the North, they consciously re-enacted the Exodus. In slave revolts and in the American Civil War they called on God for deliverance from Egyptian taskmasters. In the spiritual ‘Go Down Moses’, they re-imagined the United States as ‘Egyptland’, throwing into question the biblical construction of the nation as an ‘American Zion’. They sang of a deliverer who would tell old Pharaoh, ‘Let my People go’. They celebrated the abolition of the slave trade, West Indian emancipation, and Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation by recalling the song of Moses and Miriam at the Red Sea.

The black use of Exodus was not without its ironies. It owed more than has been recognized to the long tradition of Protestant Exodus politics, albeit reworked and subverted. African Americans took pride in the fact that Moses married an Ethiopian (Numbers 12:1), but they were embarrassed by the sanction given to slavery in the Mosaic Law, and by the Hebrews’ oppression at the hands of African Pharaohs. Yet Exodus spoke to African American experience like no other text. Like the Children of Israel, their Red Sea moment was followed by a long and bitter Wilderness experience. On the night before his assassination, Martin Luther King Jr assured his black audience that he had ‘seen the Promised Land’. Barack Obama talked of ‘the Joshua Generation’ completing the work of King’s ‘Moses Generation’, but the land of milk and honey can still seem like a distant prospect.

Heading image: Dura Europos Synagogue wall painting showing the Hebrews leaving Egypt. Adaptation by Gill/Gillerman slides collection, Yale. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Moses the liberator: Exodus politics from Eusebius to Martin Luther King Jr. appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Julia Callaway,

on 7/9/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Religion,

Philosophy,

OSO,

calvin,

Humanities,

John Calvin,

*Featured,

calvinism,

Online products,

Oxford Scholarship Online,

John Calvin as Sixteenth-Century Prophet,

Jon Balserak,

Frances Yates,

Heloise,

Lucan,

Mary Carruthers,

Pharsalia,

john calvin,

carruthers,

calvin’s,

prophetic,

farel,

Add a tag

By Jon Balserak

What is the self, and how is it formed? In the case of Calvin, we might be given a glimpse at an answer if we consider the context from which he came. Calvin was part of a society that was still profoundly memorial in character; he lived with the vestiges of that medieval culture that’s discussed so brilliantly by Frances Yates and Mary Carruthers — a society which committed classical and Christian corpora to remembrance and whose self-identity was, in a large part, shaped and informed by memory. Understanding his society may help us to understand not only Calvin but, more specifically, something of his prophetic self-consciousness.

To explore this further, I might call to memory that wonderful story told by Carruthers of Heloise’s responding to her friends when they were trying to dissuade her from entering the convent. Heloise responded to them by citing the words of Cornelia from Lucan’s poem, “Pharsalia”. Carruthers explains that Heloise had not only memorized Cornelia’s lament but had so imbibed it that it, as set down in words by Lucan, helped her explain her own feelings and in fact constituted part of her constructed self. Lucan’s words, filling her mind and being memorized and absorbed through the medieval method of reading, helped Heloise give expression to her own emotional state and, being called upon at a moment of such personal anguish, represented something of who she was; they helped form and give expression to her self-identity. The account, and Carruthers’s interpretation of it, is so fascinating because it raises such interesting questions about how self-identity is shaped. Was a medieval man or woman in some sense the accumulation of the thoughts and experiences about which he or she had been reading? Is that how Heloise’s behaviour should be interpreted?

Does this teach us anything about Calvin’s self-conception? One can imagine that if Calvin memorized and deeply imbibed the Christian corpus, particularly the prophetic books, that perhaps this affected his self-identity; that it was his perceptive matrix when he looked both at the world and at himself. To dig deeper, we might examine briefly one of Calvin’s experiences. One thinks, for instance, of his account of being stopped in his tracks by Guillaume Farel in Geneva in 1536. He recounts that Farel, when he learned that Calvin was in Geneva, came and urged him to stay and help with the reforming of the church. Farel employed such earnestness, Calvin explains, that he felt stricken with a divine terror which compelled him to stop his travels and stay in Geneva. The account reads not unlike the calling of an Old Testament prophet, such as Isaiah’s recorded in Isaiah 6 (it reads, incidentally, like the calling of John Knox as well). So what is one to make of this? This account was written in the early 1550s. It was written by one whose memory was, by this point in his life, saturated with the language of the prophetic authors. Indeed, it might be noted that Calvin claims in numerous places in his writings that his life is like the prophet David’s; that his times are a “mirror” of the prophets’ age. So is all of this the depiction of his constructed self spilling out of his memory, just as it was with Heloise?

The question is actually an incredibly fascinating one: how is the self formed? Does one construct one’s ‘self’ in a deliberate, self-conscious manner? What is so interesting, in relation to Calvin and the story just recounted, is not merely that he seems to have interpreted this episode in his life as a divine calling — so important was it, in fact, that he rehearsed it in his preface to his commentary on the Psalms, the one document in which he gives anything like a personal account of his calling to the ministry in fairly unambiguous language — but that his account should be crafted after the manner of Old Testament prophets descriptions of their callings. That is what is so intriguing and important here. It is true, as I have just said, that he wrote this many years after the event and it seems most probably to have been something which he did exercise some care over. All of that is true. But none of this takes anything away from the fact that Calvin, when he wanted to tell the story of his calling, used imagery from the prophetic books to do so. He could easily have mentioned many things or adopted various methods for explaining the way in which God called him into divine service, but he didn’t choose other methods, he turned to the prophets.

Why did he do this? Surely the answer to that question is complicated. But equally certain, it seems to me, is the fact that his ingesting of the prophetic writings represents a likely element in such an answer. For if, as Carruthers argues, memory is the matrix of perception, then Calvin’s matrix was profoundly biblical and, especially, prophetic. Naturally, much could be said by way of explaining why he interpreted this episode in his life in the way that he did. But the fact that his mind turned towards this prophetic trope says an immense amount about Calvin and the resource by which he interpreted himself and his life.

Jon Balserak is currently Associate Professor of Religious Studies at the University of Bristol. He is an historian of Renaissance and Early Modern Europe, particularly France and the Swiss Confederation. He also works on textual scholarship, electronic editing and digital editions. His latest book is John Calvin as Sixteenth-Century Prophet (OUP, 2014).

To learn more about John Calvin’s idea of the self, read “The ‘I’ of Calvin,” the first chapter of John Calvin as Sixteenth-Century Prophet, available via Oxford Scholarship Online. Oxford Scholarship Online (OSO) is a vast and rapidly-expanding research library. Launched in 2003 with four subject modules, Oxford Scholarship Online is now available in 20 subject areas and has grown to be one of the leading academic research resources in the world. Oxford Scholarship Online offers full-text access to academic monographs from key disciplines in the humanities, social sciences, science, medicine, and law, providing quick and easy access to award-winning Oxford University Press scholarship.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post John Calvin’s prophetic calling and the memory appeared first on OUPblog.

By: AlyssaB,

on 7/7/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

augustine,

Julian of Norwich,

Humanities,

Dietrich Bonhoeffer,

John of the Cross,

John Calvin,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

irenaeus,

thomas aquinas,

origen,

Athanasius,

Basil of Caesarea,

Dorthee Solle,

F. D. W. Schleiermacher,

Francis of Assisi,

Gregory of Nazianzus,

Gregory of Nyssa,

Hans Urs von Balthasar,

John Chrysostom,

John Hick,

Journey Back to God,

Jurgen Moltmann,

Karl Barth,

Karl Rahner,

Mark S. M. Scott,

Martin Luter,

Miroslav Volf,

Origen of Alexandria,

Origen on the Problem of Evil,

Sarah Coakley,

Books,

Religion,

Philosophy,

Add a tag

By Mark S. M. Scott

Imagine for a moment that through a special act of divine providence God assembled the greatest theologians throughout time to sit around a theological round table to solve the problem of evil. You would have many of the usual suspects: Athanasius, Augustine, Thomas Aquinas, Martin Luther, John Calvin, and Karl Barth. You would have the mystics: Gregory of Nyssa, Julian of Norwich, Catherine of Sienna, Teresa of Ávila, and Thomas Merton. You would have the scholastics: Anselm, Peter Lombard, Bonaventure, and John Duns Scotus. You would have the newcomers: Jürgen Moltmann, Sarah Coakley, and Miroslav Volf. You might even have some unknown names and faces. Feel free to place your favorite theologian around the table. With these diverse and dynamic minds, you could expect to have a spirited conversation.

If you were to moderate the discussion around our massive oak table you would have the daunting task of keeping pace with these agile intellects and perhaps of negotiating a few inflated egos. It might be difficult to get a word in edgewise. Augustine would be affable and loquacious. Aquinas would be precise and ponderous. Luther would be humorous and polemical. But where would Origen of Alexandria (c. 185-254) fit in, the greatest theologian of Eastern Christianity? What would he say about the problem of evil? All agree he deserves an honored seat at the table, but often others around the table suck all the oxygen out of the room, leaving little air for his profound insights, particularly on the problem of evil, which anticipate later developments while also reflecting his distinctive intellectual milieu. Let’s imagine how the conversation might go.

![Disputa di Santo Stefano fra i Dottori nel Sinedrio by Vittore Carpaccio [Public domain or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Vittore_Carpaccio_059.jpg)

Disputa di Santo Stefano fra i Dottori nel Sinedrio by Vittore Carpaccio [Public domain or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

: “Welcome all. I’ve been asked to begin our discussion. Let me say first that the problem of evil represents the most formidable conceptual challenge to theism.”

Augustine: “I agree, but the problem’s resolved once we realize that evil doesn’t exist per se, like a malevolent substance, it’s simply the privation of the good. At any rate, God doesn’t create evil, we do, and God eventually brings good out of evil, so evil doesn’t have the final say.”

Sarah Coakley: “It can’t be settled that easily. I’m suspicious of grand theological narratives that simplify conceptual complexities. Let’s retrieve some neglected voices on the problem.”

Gregory of Nazianzus: “I’ve written a theological poem about it that I’d like to share.”

Basil of Caesarea: “Please don’t. I can’t sit through another one of your theological poems.”

Gregory of Nazianzus: “Fine. I’m out of here. I didn’t want to come in the first place.”

Jürgen Moltmann: “That was a little rude, Basil, you know Greg’s sensitive, especially about his theological poetry, but let’s get back to the topic at hand. We can’t answer the theodicy question in this life, but we can’t discard it either. All we can do is turn to the God who suffers with, from, and for the world for solidarity with us in our suffering. Only the suffering God can help.”

Dietrich Bonhoeffer: “I couldn’t have said it better myself.”

Karl Rahner: “The problem of evil is a fundamental question of human existence.”

John of the Cross: “I have endured many dark nights agonizing over it.”

Julian of Norwich: “Fear not, brother John, all will be well.”

John Calvin: “Not for those predestined to the fires of hell, but that’s part of the mystery of divine providence, which is inviolable, so in a refined theological sense, all will be well.”

Julian of Norwich: “I think we have different visions of what wellness means.”

Martin Luther: “You’re all crazy casuists. We’re probing into the deeps of divine mystery. We’re way out of our depth. We’re just small, sinful worms: we can’t possibly solve these riddles.”

F. D. W. Schleiermacher: “Settle down, Martin, we’re just talking. What do you think, Karl?”

Karl Barth and Karl Rahner (simultaneously): “Which Karl?”

Miroslav Volf: “Let’s give the Karls a pass. We heard enough from them last time, and we want to make room for others. Barth would probably just talk about ‘nothingness’ anyway.”

Hans Urs von Balthasar: “Origen, you’ve been quiet, and you haven’t touched your food, what are your thoughts on the problem of evil? Won’t you give us the benefit of your deep erudition?”

Origen: “I’ve often pondered the question of the justice of divine providence, especially when I observe the unfair conditions people inherit at birth. Some suffer more than others for no apparent reason, and some are born with major disadvantages, such as blindness or poverty.”

Dorthee Sölle: “I appreciate your attentiveness to the lived experience of suffering, Origen, and not just the theoretical problem of how to reconcile divine goodness and omnipotence with evil.”

Gregory of Nyssa: “Me too, but how do you account for the disparity of fortunes in the world? How do you preserve cosmic coherence in the face of so much injustice and misfortune?”

Origen: “I’ll tell you a plausible story that brings many of these theological threads together. Before the dawn of space and time, God created disembodied rational minds, including us. We existed in perfect harmony and happiness until through either neglect or temptation or both we drifted away from God. Since all reality participated in God’s goodness, we were in danger of drifting out of existence altogether the further we strayed from our original goodness, so God, in his benevolence, created the cosmos to catch us and to enable our ascent back to God. Our lot in life, therefore, reflects the degree of our precosmic fall, which preserves divine justice. The world, you see, exists as a schoolroom and hospital for fallen souls to return to God. Eventually, all may return to God, since the end is like the beginning, but not until undergoing spiritual transformation. We must all traverse the stages of purification, illumination, and union, both here and in the afterlife, until our journey back to God is complete and God will be all in all.”

John Hick: “That makes perfect sense to me.”

Irenaeus: “Should you really be here, John? That’s a little far out there for me, Origen.”

Athanasius: “Origen clearly has a complex, subtle mind that doesn’t lend itself to simplification. It’s a trait of Alexandrian thinkers, who are among the best theologians in church history.”

John Chrysostom: “Spare me.”

Augustine: “I think I see what Origen means, especially about the origin and ontological status of evil and God’s goodness. It’s not too far from my thoughts, except for his speculative flights.”

Thomas Aquinas: “Our time is up. We haven’t solved the problem of evil, but we seem confident that God ultimately brings good out of evil, however dire things seem, and that’s a start.”

Francis of Assisi: “Let’s end in prayer.”

Thank goodness Hans Urs von Balthasar asked for Origen’s opinion, since I doubt he would have offered it otherwise. What our imaginary theological roundtable and fictitious dialogue reveals, hopefully, is that there are a variety of voices in theology that speak to the problem of evil. Some, such as Augustine and Aquinas, are well known. Others, such as Origen, have been neglected, partly because of his complicated reception, and partly because of the subtlety and originality of his thought.

Mark Scott is an Arthur J. Ennis Postdoctoral Fellow at Villanova University. He has published on the problem of evil in numerous peer-reviewed journals in addition to his book Journey Back to God: Origen on the Problem of Evil.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Theodicy in dialogue appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Julia Callaway,

on 5/27/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

Religion,

prophet,

holbein,

Europe,

calvin,

Humanities,

John Calvin,

*Featured,

calvinism,

John Calvin as Sixteenth-Century Prophet,

Jon Balserak,

balserak,

Add a tag

By Jon Balserak

For some, it was no surprise to see a book claiming that John Calvin believed he was a prophet. This reaction arose from the fact that they had already thought he was crazy and this just served to further prove the point. One thing to say in favor of their reaction is that at least they are taking the claim seriously; they perceive correctly its gravity: Calvin believed that he spoke for God; that to disagree with him was to disagree with the Almighty ipso facto.

The belief may, of course, appear utterly astonishing and bizarre to us today. While I’m sympathetic with such astonishment, I don’t share it. This is not necessarily because I believe Calvin was a prophet. It’s rather because I know him well enough to know that such a belief is entirely in keeping with his character and I suppose I’ve grown accustomed to it. Most of what comes out of his mouth or flows from his pen carries with it, it seems patently clear to me, a prophetic tone and energy. There’s no question in my mind that he held that the heavens themselves opened when he opened his mouth.

I have friends who ask with some chagrin: “didn’t Calvin feel the same sense of utter uncertainty, confusion, and awkwardness with respect to his own place in the universe that people in the twenty-first century do? Wasn’t he aware of his own weaknesses?” If so, the logic follows, how could he have become convinced that he was a divine messenger since this assumes a certain sense of faultlessness? For one of us to believe ourselves a prophet seems impossible, so, what of Calvin? Didn’t his inner reservations and neuroses weigh on his self-conception and convince him that he couldn’t possibly be the mouthpiece of the Divine? My answer is a simple “no.” I don’t think he believed that he erred in his service of God. Ever.

Let us recall that it’s Calvin who indicted the greatest theologians with the charge that they had mixed hay with gold, stubble with silver, and wood with precious stones (a reference to the Apostle Paul’s warning to those who had corrupted their labors in God’s service in 1 Corinthians 3: 15). He indicted Cyprian, Ambrose, Augustine, and some from what he referred to as more recent times, such as Gregory and Bernard. He said of these individuals that they could only be saved on the condition that God wipe away their ignorance and the stain which corrupted their work. They could only be saved as through fire. He even said this of Augustine, the Theologian par excellence for everyone in Early Modern Europe. Let us recall as well that Calvin could write in 1562, just two years before he died, that if anyone were his enemy, then they were the enemies of Christ. He goes on in this writing, entitled Responsio ad Balduini Convicia, to say that he had never taken up a position out of a hostile personal motive or being prompted by spite. He insists, in fact, in language that is astounding to read that anyone who is his enemy feels this way about him because they oppose the good of the church and they hate godly teaching. This is Calvin. This is the prophet; the one to whom the mantle of Elijah had been passed.

The natural question to ask at this point is whether Calvin believed that his writings should be added to the canon of Scripture? It might seem only logical, according to what I’m arguing, that he did. However it would, of course, be extremely difficult to justify such a claim. But I don’t think that’s all that can be said on the question. For there is a logic to the idea that not only Calvin but also Zwingli, Luther, Knox, and others who believed themselves raised up as prophets might have thought this. There are, moreover, numerous vocational, temperamental, theological, strategic, psychological, doctrinal, and relational reasons that would need to be taken into account before drawing a conclusion one way or the other on the question. I don’t put it out of the realm of possibility that Calvin could have believed this, at least at some level. He did, after all, tell his fellow ministers on his death bed that they were to “change nothing,” suggesting that the foundation he had laid was perfect and, thus, that the repository representing that foundation—namely, his biblical commentaries, lectures, theological treatises, and magnum opus, The Institutes of the Christian Religion—should serve as the origin from which the Christian church was to be rebuilt. So I would not be utterly shocked if he did, in fact, believe that his oeuvre should be made part of the canon of Scripture. Unfortunately, we will never know.

Jon Balserak is currently Associate Professor of Religious Studies at the University of Bristol. He is an historian of Renaissance and Early Modern Europe, particularly France and the Swiss Confederation. He also works on textual scholarship, electronic editing and digital editions. His latest book is John Calvin as Sixteenth Century Prophet (OUP, 2014).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post John Calvin’s authority as a prophecy appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 2/13/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

planets,

This Day in History,

Europe,

copernicus,

martin luther,

Inquisition,

galileo,

Galileo Galilei,

Pope Urban VIII,

John Calvin,

*Featured,

Physics & Chemistry,

higher education,

Science & Medicine,

this day in world history,

Copernican theory,

Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems,

Nicolas Copernicus,

copernican,

galileo’s,

1633,

summoned,

Add a tag

This Day in World History

February 13, 1633

Galileo arrives in Rome for trial before Inquisition

Source: Library of Congress.

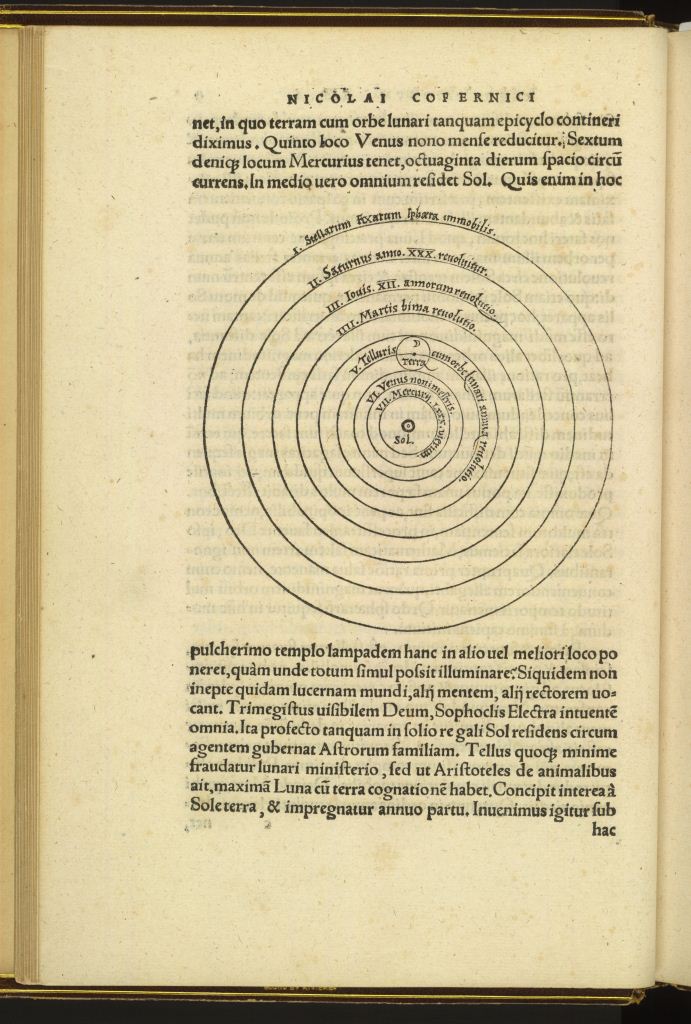

Sixty-nine years old, wracked by sciatica, weary of controversy, Galileo Galilei entered Rome on February 13, 1633. He had been summoned by Pope Urban VIII to an Inquisition investigating his

Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems. The charge was heresy. The cause was Galileo’s support of the Copernican theory that the planets, including Earth, revolved around the sun.

Nicolas Copernicus had published his heliocentric theory in 1543. His ideas were condemned by religious leaders — not only Catholic ones but also Protestants Martin Luther and John Calvin — because they contradicted the Bible. Slowly, though, astronomers began to accept the sun-centered universe.

Galileo’s own acceptance, forged in the 1590s, grew stronger in 1609, when he used a new invention, the telescope, to study the planets. Discovering that the Moon had craters, Jupiter was orbited by moons, and Venus had phases like the Moon, he rejected the accepted belief that the heavens were fixed, perfect, and revolving around Earth.

Church authorities, however, objected to a 1613 letter he wrote supporting the Copernican theory. At a hearing, he was told not to actively promote Copernican ideas. A document placed in the records of the proceeding went further, saying he was ordered never to discuss the theory in any way, but evidence suggests that Galileo’s understanding the document was planted after the meeting by enemies.

By the late 1620s, Galileo believed that Pope Urban would be more open to his ideas than earlier popes. He wrote the Dialogue as a conversation between a Copernican and an adherent of the Church’s geocentric theory, hoping to escape condemnation by presenting both views. The ploy failed, and he was summoned. The panel of cardinals decided to ban his book, force him to abjure Copernican ideas, and sentence him to imprisonment. A few months later, the old man was released to his home, where he lived until 1642.

“This Day in World History” is brought to you by USA Higher Education.

You can subscribe to these posts via RSS or receive them by email.

![Disputa di Santo Stefano fra i Dottori nel Sinedrio by Vittore Carpaccio [Public domain or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Vittore_Carpaccio_059.jpg)