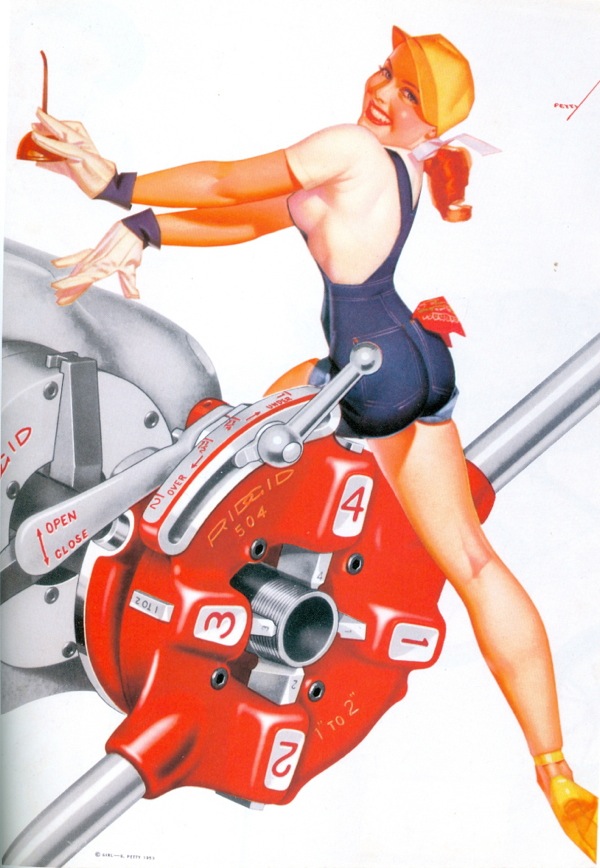

A pinup from artist George Petty, alluded to in Prof. Lepore’s piece

I kind of missed the tidal ebb and flow over Jill Lepore’s analysis of A-Force in the New Yorker while I was at TCAF. I saw it in my feed and figured it would ignite some debate but I was misled by the title on the piece

Looking at Female Superheroes with Ten-Year-Old Boys

as opposed to the internet title of the piece

Why Marvel’s Female Superheroes Look Like Porn Stars

which is a bit more clickbaity.

But what no one seems to have commented on is that MARVEL SENT THE NEW YORKER AN ADVANCE COPY OF A-FORCE! The issue doesn’t go on sale until May 20th, but here it is:

The morning after we saw “Age of Ultron”—a sleepover was involved—Captain Comics and Mr. What? and I read the first issue of “A-Force” at the kitchen table, unheroically, over waffles. I asked the captain to tell me who the women on the cover were: a swarm of female superheroes.

“She-Hulk, Phoenix, Scarlet Witch, Storm, Medusa, Rogue, Wasp, Electra,” he began. “Rescue, Miss—no, Miss Marvel, Black Widow,” he trailed off, vaguely. “I think that’s Dazzler…”

As you probably know, the co-author of the comic, G. Willow Wilson, gave a spirited rebuttal to Lepore’s musings over sueperheroine’s descent from pin-ups of the 30s:

So I was a bit surprised that someone who obviously values rigorous scholarship would analyze the first issue of a crossover event without any apparent knowledge of what a crossover event is, or what the heavily tongue-in-cheek “feminist paradise,” Arcadia, represents in the context of the Secret Wars and the wider Marvel Universe. (Does she know about the zombies? Somebody please tell her about the zombies.) Thus decontextualized, what Dr. Lepore is left with is a cover depicting a bunch of characters about whom she admits to knowing nothing, and one fifth of a story, which is perhaps why her analysis reads as so perplexingly shallow, even snarky.

As sympathetic as I am to Wilson, and supportive of the idea of an all-woman Avengers, there are a few people in the world—mostly history professors at Harvard, like Lepore, I suppose—who don’t know what a crossover event is. They may not even care. Lepore was responding to one set of tropes, while Wilson writes that the comic was created with knowledge of those same tropes:

We, the creators and editors (three women and a gay dude, by the way) are aware that the characters in A FORCE come from a bewildering mashup of genres and mythologies and time periods. That’s the whole point. A FORCE comes out of a very specific conversation about gender in comics that has been evolving rapidly in the past few years, driven as much by fandom as it is by creators and editors. Across the industry, we have been systematically un-fridging (I’ll let Dr. Lepore google that one) female characters who may have gotten short shrift in the past, looking at their backstories, and discovering, as a community, what has been left unsaid. And in A FORCE, we’ve put them all together–for the first time.

I was frankly, more interested in the story suggested by the visible title, examining just how tweener boys, the traditional audience for superheroes, actually respond to female characters, a reaction seemingly at the root of the dearth of Black Widow and Gamora merchandise, as well as the male audience that many observers to comics still presume. Lepore did quiz her kids a bit, but didn’t dig in:

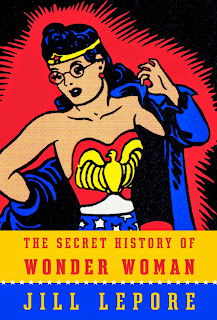

“All the girls here have, like, gigantic cleavages,” Captain Comics said, giggling.

“Why do they have gigantic cleavages?” I asked. Did it seem inevitable to these little boys, I wondered, that women would be drawn this way?

“Because they’re girls, Mom,” Mr. What? said. “What else is going to happen?” And he laughed, because it was funny, and he knew I would find that funny—the idea that nothing else was possible—the way it’s funny when Jessica Rabbit says, “I’m not bad. I’m just drawn that way.” Alas, the Avengers are not funny, and neither are the She-Avengers.

I’d also like to draw attention to another rebuttal that Wilson linked to that hasn’t gotten as much attention, written by Leia Calderon, a member of the retail group the Valkyries:

Perhaps you were concerned with how much of female superheroes are drawn for the male gaze, which is a completely valid concern. Let’s talk about how to fix that. How do we reclaim She-Hulk from the fantasies of teenage boys, if that’s all a grown woman like yourself sees when she opens A-Force? I pictured She-Hulk as she is and turned an imaginary boob-dial in my head to reduce her cup-size… and my stomach churned. It felt like body-shaming a powerful character that I adore, and would adore no less if she had a different figure than the one she’s had for almost 25 years. I understand your superficial criticism, but not your implied solution.

Obviously, there are some deep cultural forces at play here, and one would hope that A-Force will be able to transcend them. I guess I’ll have to wait until May 20th like everyone except the Lepore household to find out.

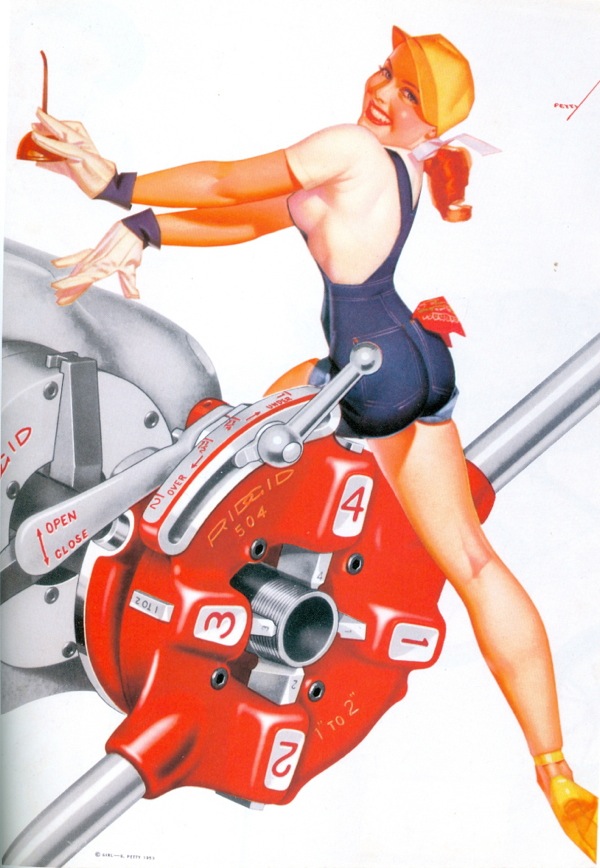

I recently read Jill Lepore's

The Secret History of Wonder Woman alongside Noah Berlatsky's

Wonder Woman: Bondage and Feminism, which had the

bad luck to be published at nearly the same time. The two books complement each other well: Lepore is a historian and her interest is primarily in the biography of

William Moulton Marston, the man who more or less invented Wonder Woman, while Berlatsky's primary interest is in analyzing the content of the various Wonder Woman comics from 1941-1948.

Lepore's book is a fun read, and it does an especially good job of showing the connections between late 19th-/early 20th-century feminism and the creation of Wonder Woman, particularly the influence of the birth control crusader and founder of what became Planned Parenthood,

Margaret Sanger. The connection to Sanger, as well as much else that Lepore reports, only became publicly known within the last few decades, as more details of Marston's living arrangements emerged: he lived in a polyamorous relationship with his legal wife, Elizabeth, and with his former student, Sanger's niece Olive Byrne (who after Marston's death in 1948 lived together for the rest of their very long lives). Some of the most fascinating pages of Lepore's book are not about Wonder Woman at all, but about the various political/religious/philosophical movements that informed the lives of Marston and the women he lived with. She also spends a lot of time (too much for me; I skimmed a bit) on Marston's academic work on lie detection and his promotion of the

lie detector he invented. As she chronicles his various struggles to find financial success and some sort of renown, Lepore's Marston seems both sympathetic and exasperating, a bit of a genius and a bit of a con man.

Because she had unprecedented access to the family archives, and is an apparently tenacious researcher in every other archive she could get access to, Lepore is able to provide a complex view not only of Marston and his era, but especially of the women in his life — the women who were quite literally the co-creators of Wonder Woman: Marjorie Wilkes Huntley, Elizabeth Marston, and Olive Byrne. She is especially careful to document the contributions of Joye Hummel, a 19-year-old student in one of Marston's psychology classes who, after Oliver Byrne graded her exam (which "proved so good she thought Marston could have written it") was brought in to help work on Wonder Woman. Originally, Marston thought he could use Hummel as a source of current slang, and to do some basic work around the very busy office. "At first," Lepore writes, "Hummel typed Marston's scripts. Soon, she was writing scripts of her own. This required some studying. To help Hummel understand the idea behind Wonder Woman, Olive Byrne gave her a present: a copy of Margaret Sanger's 1920 book,

Woman and the New Race. She said it was all she'd need." When Marston became ill first with polio and then cancer, Hummel became the primary writer for many of the Wonder Woman stories. (Lepore provides a useful index of all the Marston-era Wonder Woman stories and who worked on them, as best can be determined now.)

|

| Lou Rogers, 1912 |

|

| H.G. Peter, 1943/44 |

Lepore also has a few pages on

Harry G. Peter, the artist who brought Wonder Woman to life, and does a fine job of showing how Peter, who was about 60 when he got the Wonder Woman assignment, was also influenced by the iconography of the suffrage movement. He had been an illustrator for

Judge alongside the far better known

Lou Rogers, who created some of the most famous artwork of the later suffrage movement. Lepore writes: "To Wonder Woman he brought, among other things, experience drawing suffrage cartoons." (Not a lot seems to be known about Peter — Lepore has a note stating that "details about Peter's life are difficult to find, largely because, after his death in 1958, his estate fell into the hands of dealers, who have been selling off his papers and drawings, one by one, for years, to private collectors.")

Marston was hardly a perfect man or role model, and one of the things the story of his life and the lives of the women around him shows is the complexity of trying to live outside social norms. While Marston had some extremely progressive ideas not only for his own time but for ours as well, he was also very much a product of his era and location. That's no earth-shaking insight, but Lepore does a good job of reminding us that for all his liberalism and even libertinism, Marston still had many of the flaws of any man of his age, or of ours. He truly seemed to dislike masculinity, and yet lived at a time when it was difficult to imagine any way of living outside of it or its hierarchies, and his ways of analyzing the effect of masculinity and patriarchy were very much bound by his era's common notions of gender, biology, propriety, and race. Lepore does a fine job of showing not only how the assumptions and discourses of a particular time, place, and class situation shape notions of the possible in Marston's life, but also in the lives and politics of the early 20th century feminist movement.

However, Lepore's book is seriously under-theorized, and that's where Berlatsky comes in.

The Secret History of Wonder Woman is aimed at a general audience, and Lepore is a historian, not a theorist. This would be less of a problem if Marston's life and work didn't scream out for the insights of someone familiar both with feminist theory and, especially, queer theory. (Lepore actually seems quite uncomfortable with the sexual elements of the story, and even more so in an

interview she did for NPR's

Fresh Air, where she can't help giggling over it all.) Berlatsky makes the excellent choice to take the queer elements seriously. He organizes his book into three large chapters, the first focusing on feminism and bondage, the second on pacifism and violence, the third on queerness. A brief introduction gives background on the comic and its creators; the conclusion looks at Wonder Woman's (sad) fate after Marston's death.

Berlatsky's writing is accessible — he's perhaps best known for founding the

Hooded Utilitarian blog, so he's used to writing for a non-academic audience. (The blog has tons of Wonder Woman

material, including lots from before the book, so you can follow Berlatsky's thinking as it develops, get more information and imagery, and see Berlatsky in conversation with many thoughtful, informed commenters and guest bloggers.) Though his prose is not heavily academic, Berlatsky is well-versed in comics scholarship and has some good knowledge of both feminist and queer theory, all of which he uses to fill a relatively short book with a real density of ideas. It helps that the early Wonder Woman comics are so strange and suggestive; even after Berlatsky's most thorough analyses, it still feels like there's plenty left to say. (Which is no slight to him.)

In the introduction, Berlatsky describes the 1941-1948 Wonder Woman comics as “…an endless ecstatic fever dream of dominance, submission, enslavement, and release.” His first chapter then offers various ideas about bondage and fantasy, with the majority of its pages devoted to a complex reading of

Wonder Woman #16 (you can see Berlatsky first thinking about this issue in

a 2009 post at HU that gives a good overview the plot and substance, as well as lots of samples of the art). Ultimately, Berlatsky argues that the story is a representation of, among other things, incest ... and I'm not sure I followed him there. Something about the analysis feels forced to me, though I don't have any good rebuttal to it.

Chapter Two was more convincing for me, as Berlatsky has some cogent insights about violence, maleness, and superheroes: "Looking at Spider-Man's origin makes clear, I think, that superhero violence is built on, and reliant on, masculinity." Is Wonder Woman different? "It is certainly true that, in Marston and Peter's initial conception, Wonder Woman, like other heroes, often solves problems in the quintessentially superhero manner. That is, she hits things." Wonder Woman also participated in World War II, as the first appearance of her character coincided with the US entry into the war. "It was natural that Wonder Woman's alter-ego, Diana Prince, worked as a secretary for army intelligence, just as it was natural for Wonder Woman herself to foil spy rings and Nazi plots. Superheroes and war went together as surely as did goodness and power." But Marston wanted Wonder Woman to be something other than just a fist-fighting warrior, thrilled to hit anybody she could find. She is a fighter, but, Berlatsky says, a pragmatic fighter for peace: "The Nazis embody war; therefore, fighting the Nazis is fighting on behalf of peace. Or, more broadly, masculinity embodies war; therefore, fighting on behalf of an America that Marston sees as feminine means fighting on behalf of peace."

Berlatsky then goes on to show how some of Marston's psychological and social theories (particularly about the force of love) find expression through the Wonder Woman stories. Coming off of Chapter One, I was a bit skeptical about all this, but by the end of Chapter Two, I'd pretty well been convinced. The evidence Berlatsky marshalls from Marston's writings, particularly his book

Emotions of Normal People, is compelling. (

Emotions of Normal People itself is a fascinating source. Lepore describes it thus: "

Emotions of Normal People is, among other things, a defense of homosexuality, transvestitism, fetishism, and sadomasochism. Its chief argument is that much in emotional life that is generally regarded as abnormal…and is therefore commonly hidden and kept secret is actually not only normal but neuronal: it inheres within the very structure of the nervous system." Berlatsky uses it well in the second and third chapters to show where some of the oddest Wonder Woman moments derive from.)

Chapter Three is what really won me over, I will admit, particularly because Berlatsky brings in ideas from

Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick and

Julia Serano to explore the implications of various situations and images throughout

Wonder Woman. As it explores Marston's lesbophilia and the manifold queer implications of the Marston-era Wonder Woman comics, the chapter ranges across all sorts of subject matter, including, among other things, James Bond and Pussy Galore (from

Goldfinger). Berlatsky notes that unlike Ian Fleming's women "Marston's women don't want the penis; rather, his men want the absence of a penis — a unique female power."

There's too much good stuff in this chapter for me to summarize, but one especially interesting bit involves the relationship of the vagina and penis in Marston's idea of sex. Berlatsky quotes

Emotions of Normal People: "The [woman’s] captivation stimulus actually evokes changes in the male’s body designed to enable the woman’s body to capture it physically. …[During sex] the woman’s body by means of appropriate movements and vaginal contractions, continues to captivate the male body, which has altered its form precisely for that purpose." Berlatsky summarizes: "Penises don't defile Marston's vaginas; on the contrary, Marston's vaginas swallow up penises."

(If that sentence doesn't make you want to read this book, then there's really no hope for you!)

Berlatsky then shows how these ideas play out in

Wonder Woman. "Men in

Wonder Woman are never as disempowered and objectified as women in James Bond or gangsta rap or Gauguin — a couple thousand years of tropes don't just vanish because you have a vision of active vaginas. Thus, when Marston flips the binary from masculine/feminine to feminine/masculine, the result is not simple hierarchy inverted. Rather, it's heterosexuality inverted — which is another way of saying it's queer." He then develops this idea to show that "For Marston, essentialism and queerness are not in conflict. Instead, queerness is anchored in, and made possible by, an essentialist vision of femininity. Femininity for Marston doesn't just appear to be strong and love; it is strong and loving. Women for him capture men not just as metaphor but as scientific fact. And it is from those beliefs that you get [in

Wonder Woman #41] Sleeping Beauty rescued/captured by a semisentient vagina, or men turning into women on Paradise Island. Femininity makes the world safe for polyamory. You can't have the second without the first."

It's these sorts of insights that would have brought more nuance and complexity to Lepore's portrayal of the role of early 20th-century feminism in Marston's creation of Wonder Woman, but we can be grateful that we can read the two books together.

I've only barely touched on Berlatsky's arguments here, and may have misrepresented them simply by trying to summarize, so if they seem especially bizarre or off-base, check the book. (They may still be bizarre, but to my thinking, at least, they're more often convincing than not.) It's an extremely difficult book to summarize because its ideas and arguments are carefully woven together, even as, in an initial reading, it all often feels quite off-the-cuff, like an improvised high-wire act.

Wonder Woman has suffered in popularity in comparison to male superheroes, and even in this age of wall-to-wall superhero media, a planned Wonder Woman movie has had all sorts of problems getting started. Of course, no Wonder Woman is going to be Marston's Wonder Woman, which is one reason why it's unfortunate that DC hasn't been able to finish re-releasing the 1941-1948 Wonder Woman stories — some, as far as I can tell, have never been reprinted at all, and the most comprehensive collection, part of the

DC Archive Editions, petered out after seven volumes, ending with issues from 1946. (

Wonder Woman: The Complete Newspaper Comics is quite good.) For the casual reader, the material in the

Wonder Woman Chronicles, which got up to three volumes before apparently stopping in 2012, works well, though some of the best and craziest comics come later. There just doesn't seem to be enough demand from readers, and so a trove of wondrously strange material remains generally unavailable.

Perhaps Lepore and Berlatsky's books will create enough new interest to spur DC at least to finish the Archive Edition releases. Personally, what I'd most like to see is a 300-400 page "Best of the Marston Years" collection edited by Berlatsky, because only the real die-hards need all of the various

Wonder Woman stories, and it would be nice to have a one-volume edition of the most engaging and exemplary material.

We all know that William Moulton Marston, the creator of wonder Woman, was a bit odd. He had two “wives” and he was heavy into bondage. But did you know that one of the women he shared his life with was the niece of birth control pioneer Margaret Sanger—who liked to wear bracelets? And that Sanger may have been the inspiration for Wonder Woman?

We all know that William Moulton Marston, the creator of wonder Woman, was a bit odd. He had two “wives” and he was heavy into bondage. But did you know that one of the women he shared his life with was the niece of birth control pioneer Margaret Sanger—who liked to wear bracelets? And that Sanger may have been the inspiration for Wonder Woman?

These are only a few of the historical facts uncovered by Harvard history professor Jill Lepore in her upcoming volume The Secret History of Wonder Woman . It turns out a lot of that history is very secret, but Lepore has gone through Marston’s hitherto unseen private papers, and correspondence from his wife, Sadie Elizabeth Holloway, and Olive Byrne, the third housemate, and niece of Sanger. Lepore is also a staff writer at The New Yorker and a few weeks back her article for that magazine laid out the bare bones of the story.

. It turns out a lot of that history is very secret, but Lepore has gone through Marston’s hitherto unseen private papers, and correspondence from his wife, Sadie Elizabeth Holloway, and Olive Byrne, the third housemate, and niece of Sanger. Lepore is also a staff writer at The New Yorker and a few weeks back her article for that magazine laid out the bare bones of the story.

In 1917, when motion pictures were still a novelty and the United States had only just entered the First World War, Sanger starred in a silent film called “Birth Control”; it was banned. A century of warfare, feminism, and cinema later, superhero movies—adaptations and updates of mid-twentieth-century comic books whose plots revolve around anxieties about mad scientists, organized crime, tyrannical super-states, alien invaders, misunderstood mutants, and world-ending weapons—are the super-blockbusters of the last superpower left standing. No one knows how Wonder Woman will fare onscreen: there’s hardly ever been a big-budget superhero movie starring a female superhero. But more of the mystery lies in the fact that Wonder Woman’s origins have been, for so long, so unknown. It isn’t only that Wonder Woman’s backstory is taken from feminist utopian fiction. It’s that, in creating Wonder Woman, William Moulton Marston was profoundly influenced by early-twentieth-century suffragists, feminists, and birth-control advocates and that, shockingly, Wonder Woman was inspired by Margaret Sanger, who, hidden from the world, was a member of Marston’s family.

This week, there’s a piece Lepore has written for The Smithsonian with much of the same material but some new stuff too, such as the role of Dr. Lauretta Bender a psychiatrist who was something of the anti-Wertham:

Gaines decided he needed another expert. He turned to Lauretta Bender, an associate professor of psychiatry at New York University’s medical school and a senior psychiatrist at Bellevue Hospital, where she was director of the children’s ward, an expert on aggression. She’d long been interested in comics but her interest had grown in 1940, after her husband, Paul Schilder, was killed by a car while walking home from visiting Bender and their 8-day-old daughter in the hospital. Bender, left with three children under the age of 3, soon became painfully interested in studying how children cope with trauma. In 1940, she conducted a study with Reginald Lourie, a medical resident under her supervision, investigating the effect of comics on four children brought to Bellevue Hospital for behavioral problems. Tessie, 12, had witnessed her father, a convicted murderer, kill himself. She insisted on calling herself Shiera, after a comic-book girl who is always rescued at the last minute by the Flash. Kenneth, 11, had been raped. He was frantic unless medicated or “wearing a Superman cape.” He felt safe in it—he could fly away if he wanted to—and “he felt that the cape protected him from an assault.” Bender and Lourie concluded the comic books were “the folklore of this age,” and worked, culturally, the same way fables and fairy tales did.

With Wonder Woman finally getting a crack at being a big time character again, I’m sure all of this secret history will be sifted for evidence pro or con, and will add to the “complicated” nature of the character. I expect anyone who gets the Wonder Woman writing should probably read this book cover to cover…and so should anyone interested in the history of one of the great superheroes.

I'd like to use the word "electrifying" in the following post. I'd like to use it several times.

Because that's the word that kept coming to mind throughout our time with Jill Lepore, who last evening graced Villanova University as the third speaker in The Lore Kephart '86 Distinguished Historians Lecture Series. If I had allowed myself to wonder, theoretically, how one young woman could have already achieved so much in life—she's a professor of American History at Harvard and one of my very favorite writers at

The New Yorker; she's published books on topics ranging from the Tea Party to the origins of American identity; she's gone to Dickens camp and read 38 volumes of original Ben Franklin; her work has won the Bancroft Prize and been a finalist for the Pulitzer; she's even co-authored a novel—I stopped wondering two minutes after she walked into the room. The answer is pretty basic, pretty simple: Jill Lepore doesn't waste an ounce of her intellect on posturing or presumption. Her enthusiasm is equal to her intelligence. Her facility with language, structure, theme is all in rather happy accordance with her capacity to sleuth her way toward truth.

She was extraordinary last night. She was—here it comes—

electrifying as she spoke about Jane Franklin, Ben Franklin's sister and truest correspondent (for more on the topic, please click

here). My mother would have loved Jill Lepore. She would have sat there as I sat there, on the edge of a seat in a crowded room, happy to be in the company of one that exhilarating, that engaged.

There are so many who make an event like this happen. I'm particularly grateful to my friend Paul Steege, a Villanova University associate professor of history who sits on the speaker selection committee, to Diane Brocchi, to Father Kail Ellis, to Marc Gallicchio, and to Adele Lindenmeyr. And of course, none of this would be possible without my father, Horace Kephart, who had the foresight to create this lecture series in memory of the woman he loved.

I'll be headed to London in a few days for a very quick trip and so, in typical Beth style, I am trying to complete every single task on every single list before I get on that plane. Stupid, I know.

That means that the last few days have been consumed with the writing of the second draft of a commemorative book for a client, the back-and-forthing with an insurance agent, the prepping for a school visit at the Eighth Grade Center @ Springford, the watching of a documentary about graffiti, the blogging about Ismet Prcic's debut novel

Shards, the writing of stories for a client news magazine, the neglect of a few emails I still have to write, the repolishing of my nails, the development of a plan to put my William novel into the world, the forgetting to pick up the dry cleaning, the thinking through of my spring Penn course, the preparation for the upcoming

Jill Lepore lecture at Villanova University (wait, how does one prepare?), the reading of the first two chapters of

The Art of Fielding because it is about time, the cooking of a dinner that could have been better, the reading of a friend's forthcoming novel, the writing of verse for our holiday card, the realization that the roof is leaking again, and the completion of an adult novel that has been in the works for years. I also purchased a few early holiday gifts and made the decision—an emphatic one—that I do not like shopping. No, I do not.

{For those, who, understandably, plan to read no further, please note (see below) that this tongue-in-cheekish list was produced to make a larger point.} In the midst of all of this, I paged through (lightning speed) the December 5 issue of

Newsweek. (Frankly, I still have a lot of questions about this new iteration of

Newsweek, but those questions are for another day.) I stopped at page 61, the Omnivore page, where Diablo Cody and Charlize Theron look out upon the reader. The story is called "The Narcissist Decade," and it's an essay Cody has penned in anticipation of the December 9 release of her film "Young Adult."

"Young Adult," as it turns out, is about a not-very-nice seeming young adult author. Cody tells us: "Mavis's humble peers possess something that eludes her more each year: growth. They've matured into seasoned adults with perspective and humility, while Mavis continues to flail in a self-created hell of reality TV, fashion magazines, blind dates, and booze."

(I sincerely hope that Mavis is not meant as a stand-in for all YA authors. I sincerely hope that. I do.)

In any case, later on in the essay, Cody, whose husband has told her that she shares a number of traits with Mavis (an assertion Cody at first denies), goes on to suggest that perhaps we are all narcissists.

Before you get as offended as I did, allow me to explain. Sure, we're not all deranged homewreckers in pursuit of past glory. But if the era of Facebook and Twitter has fed any monsters, it's those of vanity, self-obsession, and immaturity. Who among us hasn't Googled an ex, or measured our own online social circle against that of a perceived rival, or snapped multiple "profile photos" in an attempt to find the best angle? Who hasn't caught herself watching an episode of "Jersey Shore" and thought, "I'm a grown-up. Why am I con

A week or so ago, when my husband and I were powerless, my father called and invited us to dinner at his home, where my mother's orchids still grow, the figurines still shine, and the sun yet goldens the rooms. Glimmers of

my mother, all. We were almost finished with this delightful repast (cloth napkins! dimmed lights! smart vegetables! organic cookies!) when my father mentioned that the Villanova University committee entrusted with the selection of a scholar for the Lore Kephart Distinguished Historians Lecture Series had made its decision, and that Jill Lepore was slated to come. She follows Pulitzer Prize winning

James McPherson and the utterly engaging

Andrew Bacevich in this role, and she will appear at the university on the evening of December 6th, details to come.

Jill Lepore happens to be one of my idols. She's not just the David Woods Kemper '41 Professor of American History at Harvard University and a staff writer for

The New Yorker. She's a woman who smiles warmly back at you from her portrait photos, despite the fact that her head is preposterously full of stuff about Charles Dickens and the Constitution, Benjamin Franklin's youngest sister and the Tea Party, eighteenth-century Manhattan and the King Philip's War (she has written or is writing books about it all). For an apparent change of pace, she's even co-authored a widely acclaimed novel called

Blindspot. And once she wrote a

New Yorker piece called "The Lion and the Mouse" (about E.B. White, Stuart Little, and the sometimes ridiculously short-sighted nature of critics and publishing houses) that was so letter perfect I didn't just blog about it

here. I wrote Ms. Lepore a gushing fan letter. Miraculously, Ms. Lepore wrote back.

Jill Lepore will be talking about the Tea Party and the Constitution in December. I'll be providing more details as I can. For now I'm simply expressing my excitement that my mother and father are working together once again to bring all of us something grander than grand.

My thanks to Paul Steege, a good friend, fine teacher, smart writer, and great soul, who remains a key member of this selection committee.

The New Yorker ran

The New Yorker ran

That’s a really funny observation about the advance copy thing. As someone who writes about comics for a mainstream online publication, Marvel is the only comics publisher that doesn’t send me anything in advance. They’re notoriously stingy about that stuff.

I enjoyed Wilson’s rebuttal but she almost lost me with her lengthy opening argument that in order to understand the context of a first issue of a comic, you need to know all about the crossover event it is spawned from. This is a losing argument that comic readers and professionals alike often can’t step outside of and see for what it is. Comics like this just don’t make sense to anyone that isn’t willing to immerse themselves in the years of stories that have come before it.

Shooter’s Dictum:

Every issue of a title is somebody’s FIRST issue of a title.

I do read every issue that DC Comics sends me, and even then, I forget what’s been happening from the previous issue. (Like “Superman’s Joker” in the Superman/Batman comic, or the overall storyline of Batman: Eternal.)

I read Secret Wars #0 as part of FCBD, but it didn’t really explain anything, or excite me enough to read the event.

@Rich – except nobody is suggesting that you have to immerse yourself in “years” of stories to understand A-Force. Only one mini series that is being published at the same time, which this is a tie-in with.

@Glenn – Yes, except that one mini-series starts by basically continuing a story that has been running in two separate Avengers comics for like 40 issues each. And that’s not counting the various threads being pulled from comics even older than that.

Actually, if Marvel sent the *New Yorker*–or, more likely, “The Secret History of Wonder Woman” author Jill Lepore personally–an advance copy of *A-Force* with that particular variant cover, Lepore’s cleavage/”porn star”-fixated response makes a bit more sense, at least in regard to how Nico Minoru, Loki (female version), and possibly Dazzler are drawn. Of course, when I saw Lepore interviewed on C-Span’s Book TV a few months ago, I got the distinct impression that she hadn’t bothered to do any research at all about what happened to Wonder Woman after the William Moulton Marston era. So if she’d never actually looked at any superheroine comics drawn by anyone more influenced by pin-uppy good girl (or bad girl) art than by the rather woodenly old-fashioned stylings of original Wonder Woman artist H.G. Peter, I suppose even the relatively fully-clothed, arms folded, “heroically posed” portrayal of the A-Force heroines shown on the non-variant *A-Force* #1 cover image that accompanied the digital version of Lepore’s article might come as a bit of a shock.

This problem is hardly specific to comics. Its in television, movies, advertising, you name it.

I don’t think I realized normal looking people had sex until I started reading Will Eisner.

Well, *I* was certainly shocked by the fact that Marvel sent someone an advance copy for review, as it was my understanding that they pretty much don’t do that. I wonder Lepore’s reaction/review will reinforce their policy of not doing that, or if all of this attention is worth it, no matter what Lepore might have said–Like, surely Lepore’s piece drew more attention to the book to people who had never heard of it than it would have convinced people planning on buying it to drop it.