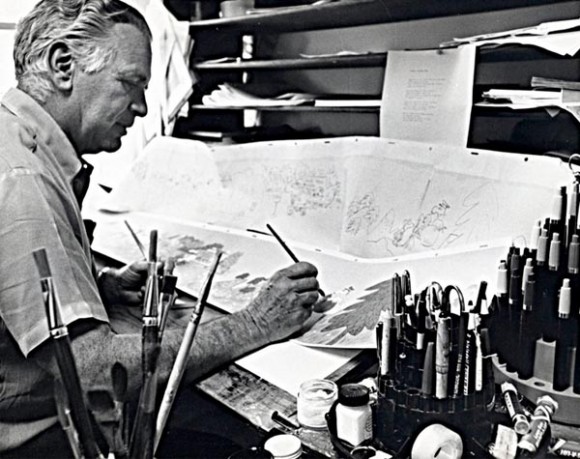

Check out our image gallery of Mel Shaw artwork, which will soon be on display at the Walt Disney Family Museum.

The post From ‘Bambi’ to ‘The Lion King,’ Disney Legend Mel Shaw Lassos a Retrospective appeared first on Cartoon Brew.

Add a Comment

Check out our image gallery of Mel Shaw artwork, which will soon be on display at the Walt Disney Family Museum.

The post From ‘Bambi’ to ‘The Lion King,’ Disney Legend Mel Shaw Lassos a Retrospective appeared first on Cartoon Brew.

Add a Comment"Inside Out" production designer Ralph Eggleston and historian John Canemaker will introduce some of the screenings.

Add a CommentThe memorably phantasmagoric finale of Fantasia is getting its own live-action spinoff.

Add a CommentWhat do long-lost sweatbox notes reveal about the creation of one of Disney's finest films?

Add a CommentAnimation historian John Canemaker talks about the process and challenges of creating the monumental new biography "The Lost Notebook: Herman Schultheis & the Secrets of Walt Disney's Movie Magic."

Add a Comment

Edward Levitt, an unsung hero of the Golden Age of animation, has died. He was 96. Levitt died on Tuesday, April 2, in Palmdale, California.

Levitt worked as a production designer, storyboard and layout artist, and background painter for thirty-five years in the animation industry. His superb skills as a designer made him a key figure during the Cartoon Modern era of the 1950s.

Ed Levitt was born in New York City on April 17, 1916 and grew up in Somers, Connecticut and Brooklyn, New York. His family moved to Los Angeles in the mid-1930s and following graduation from high school, Levitt applied to the Disney Studios in 1937. He was hired at $16.50 per week and did rotoscape tracing on Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.

The Disney studio recognized his talent as a painter, and by the end of production on Snow White, he had switched to painting backgrounds. He worked as a background artist on Pinocchio, the “Rite of Spring” segment in Fantasia and Bambi. Levitt picketed during the Disney strike of 1941. He returned after the strike was settled to work on Victory Through Air Power, but left again to enlist in the Marines in 1943. During the war, he made training films while a member of the Marine Corps Photographic Section in Quantico, Virginia.

Here are a couple examples of his paintings from Fantasia and Bambi:

After the war, Levitt became a partner in a Los Angeles-based production company called Cinemette, which was formed with ex-Marines (and Disney artists) John Chadwick, Jack Whitaker, and Keith Robinson. The studio operated between 1946-1950, and they created a number of industrial films, as well as entertainment short subjects and early TV commercials.

Levitt’s liberal politics led him to direct Grass Roots (1948), which called for establishing a world government through a revision of the United Nations charter and was partly funded by the United World Federalists. He also produced a popular anti-nuclear film Where Will You Hide? (1948), which attracted the attention of no less than Albert Einstein, who commented, “Somebody, after having seen this film, may say to you: This representation of our situation may be right, but the idea of world government is not realistic. You may answer him: If the idea of world government is not realistic, there there is only onerealistic view of our future: wholesale destruction of man by man.”

Levitt’s star rose during the 1950s when commercials and commissioned films were produced at an increasingly frenetic pace. His graphically accessible yet sophisticated style made him much sought after as a designer, storyboard and layout artist. “He was a great artist,” said animator Bill Littlejohn. “And his layouts were the best. He could animate, too. I sure liked working with him. He was so damn good at what he did. He knew the problems that the animators would face and he would design things with that in mind.”

These are a few examples of commercials and films designed and laid out by Levitt:

Through the 1950s, Levitt worked as a freelancer at more than a dozen studios including Graphic Films, Cascade Pictures, Raphael G. Wolff, Quartet Films, John Sutherland Productions, Eames Office, ERA Productions, United Productions of America, Ray Patin Productions, Academy Pictures, Churchill/Wexler Film Productions, Storyboard Inc., and Fred A. Niles Productions.

At Playhouse Pictures, Levitt worked closely with director Bill Melendez on many of the Ford spots starring the cast from the Peanuts comics. When Melendez opened his own studio in 1964, Levitt was one of the first artists he hired. “I remember Ed as being reliable, steady, pragmatic, kind and generous,” said Melendez’s son Steve, who also worked at the studio. “I know that he helped Bill in the early days not only artistically but also financially. Bill always considered Ed to be ‘The Best’, a title he did not bestow easily or often. Ed could draw anything and had a great grasp of how a film is made. He was the best layout person I have ever met.”

Levitt played a key role in designing the first Peanuts special, A Charlie Brown Christmas with backgrounds like this:

He also coined the famous credit used for many years at the end of the Peanuts specials—Graphic Blandishment. “Blandishment” is defined as “something that tends to coax or cajole,” which speaks to Levitt’s modesty and his view of the role he played in the filmmaking process.

Steve Melendez recalled that Levitt was proud of A Charlie Brown Christmas even during times of uncertainty and doubt:

“When we completed A Charlie Brown Christmas, and we all had a chance to look at the answer-print, Bill, Lee [Mendelson] and everyone else thought we were the authors of a great disaster and we would probably never make a film again. Ed was the sole voice who said, ‘Don’t be silly, this film will be shown for a hundred years!’ And he was right. I don’t know if he believed it or not, but his calm confidence gave everyone hope that perhaps things were not as bad as they seemed.”

By the early-1960s, Ed identified himself as a Cartoonist-Rancher on his income tax returns. He had begun taking animal husbandry classes at Pierce College, and had purchased a ranch in Lake Hughes, an hour’s drive north of Los Angeles, near Gorman, California. There, he planted cherry and apple orchards, and began to raise cattle.

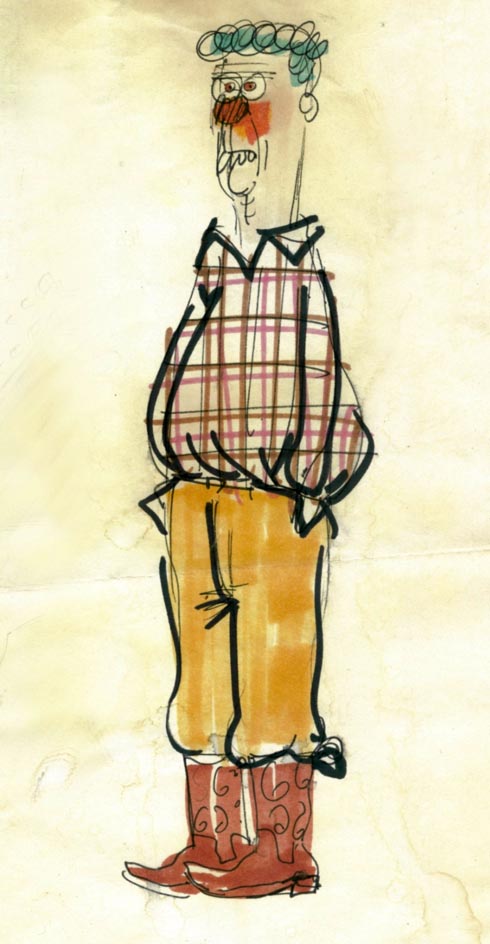

Bill Melendez made this drawing of “cartoonist-rancher Ed”:

He spent most of the 1960s working on the Charlie Brown TV specials, and also directed a couple of Babar specials for Melendez. Other Sixties projects included the titles of It’s a Mad Mad Mad Mad World, and the features Gay Purr-ee and The Incredible Mr. Limpet.

Levitt retired from animation in 1973 to become a full-time rancher and orchard owner. “As you get older,” Levitt told a newspaper reporter, “it just seems a lot nicer to sit up here in the forest and listen to the trees grow.”

Levitt is predeceased by his wife, Dorothy. He is survived by his brother, Julius Levitt; sister, Annette Priemer; his four children, Alan Cyders; Geoffrey, Dan and Paul Levitt, along with numerous grandchildren and great-grandchildren. In lieu of flowers, the family has requested that donations be made in his name to the Motion Picture & Television Country House and Hospital.

Add a Comment

This news of Michael Steinberg’s death comes as a terrible blow, a truly sad moment that we had all hoped would never arrive. Yet it leads us to reflect upon the strength, passion, and grace of Michael’s character, the intelligence and infectious joy with which he approached music and his writing, and the integrity and clear mindedness which he carried throughout his life and illness. His gift to the world extends well beyond his rich and innumerable insights into the classical music repertoire, which invite generations of enthralled readers to enter into and explore this glorious art form. Micheal’s greatest gift, I believe, was his ability to show us, through his eyes, the beauty and the goodness of our own familiar world.

On behalf of all at Oxford University Press, I extend our deepest condolences to Jorja, to Michael’s family, and to his friends and communities. He will, most sincerely, be missed. To celebrate Michael’s life and amazing career, please enjoy this excerpt from his book For the Love of Music: Invitations to Listening, co-written with Larry Rothe. More information about his amazing contributions to music and scholarship can be found at the Boston Globe and the San Francisco Chronicle.

I fell in love with music in a murky alley when I was eleven. Sometimes I ask friends when and where and how it happened to them, and they recount childhood memories of hearing a beautiful cousin play a Chopin etude, of being stunned by a broadcast of the Saint Matthew Passion, or sent into reveries lying under the family piano while Mother practiced Songs without Words. My own fall was less romantic.

More precisely, I was seduced and then proceeded to fall in love. It was Fantasia…that did me in.  I saw it just once, at the Cosmopolitan, a dingy movie house in Cambridge, England, and although this was more than sixty-five years ago, I remember it more vividly than most of the movies I’ve seen in the last sixty-five weeks. I saw it just once because as a schoolboy on threepence a week in pocket money…I couldn’t afford to go again. Besides, the guardians of Good Taste would not have encouraged, let alone subsidized, a return visit. But I also realized I did not need to see it again because the most important part was available for free. Behind the sweet little fleabag where Fantasia was playing, there was this alley where I could stand every day after school, stand undisturbed, and listen to the soundtrack of Leopold Stokowski and the Philadelphia Orchestra playing Bach, Beethoven, Schubert, and Stravinsky…

I saw it just once, at the Cosmopolitan, a dingy movie house in Cambridge, England, and although this was more than sixty-five years ago, I remember it more vividly than most of the movies I’ve seen in the last sixty-five weeks. I saw it just once because as a schoolboy on threepence a week in pocket money…I couldn’t afford to go again. Besides, the guardians of Good Taste would not have encouraged, let alone subsidized, a return visit. But I also realized I did not need to see it again because the most important part was available for free. Behind the sweet little fleabag where Fantasia was playing, there was this alley where I could stand every day after school, stand undisturbed, and listen to the soundtrack of Leopold Stokowski and the Philadelphia Orchestra playing Bach, Beethoven, Schubert, and Stravinsky…

…Not that Fantasia was my first encounter with “classical” music. I had done the first phase of my growing up in Breslau in a cultivated, affluent, German Jewish household with a Bechstein grand and a good radio (but no record player, not an uncommon lack for the day)… Going to concerts in Breslau was out because by the time I was old enough to be taken, public events of that sort were forbidden to Jews. Not knowing what I was missing, I was much more bothered by not being able to go iceskating or to the zoo anymore. So, while there was a general sense at home that music was A Good Thing, and a few names and titles were familiar…I had nearly nothing by way of actual musical sounds to tie to them…

At ten I went to England on a Kindertransport. There I spent most of the year in boarding school, the rest with the highly literate, politically aware, and quite unmusical English family that had taken me in. Even so, the paterfamilias maintained a surprising totemic reverence for two symphonies, Beethoven’s Ninth and Elgar’s Second, actually suspending his obsessive gardening when they showed up on the radio, which we still called “the wireless.” Otherwise, [their] indifference to music was complete…

All of this meant that I had to find my way to music on my own. Or, rather, it found me. Fantasia came to the rescue at the right moment, and after that it was a question of learning how to still my growing hunger… I discovered record stores, which in those days had tiny listening rooms in which one could try those imposing, shiny, black, dangerously fragile disks. (When I revisited Cambridge for the first time more than twenty years later I wanted to go into Miller’s to thank them for what, unwittingly and probably not happily, they had done for me on my journey toward music, but I am sorry to say I didn’t actually do it.)…Miller’s was a treasure trove, and I took pains to learn the schedules of the various salespeople so that no one of them would see me too often and I would not wear out my thinly based welcome…

…What have I learned? In the alley behind the Cosmo I learned…that I did not need Mickey Mouse or those bra-clad centaurettes or even the beautiful images of darting violin bows…to make the music enjoyable. I learned that music repaid repeated listening. Most music anyway… I learned to pay attention, because if I missed something it was gone… I learned that my focus changed from details to at least something like the whole, from the raisins to the cake. And I learned that there was a lot to hear in some of those pieces and that they did not cease to be full of surprises. I could of course not have articulated any of this then…

…What else did I eventually learn? To pay heed to my first reactions but also not to take them too seriously and certainly not to assume that they have permanent value. Not to think too much at the beginning and not to think at all about what I thought I was maybe supposed to be thinking. To be patient or—better—suspenseful, to wait and see how the piece or I might change (the former is of course an illusion)… That in the end the only study of music is music, that good program notes and pre-concert talks are helpful ways of showing you the door in the wall and of turning on some extra lights, but that the only thing that really matters is what happens privately between you and the music. That, as with any other form of falling in love, no one can do it for you and no one can draw you a map. That listening to music is not like getting a haircut or a manicure, but that it is something for you to do. That music, like any worthwhile partner in love, is demanding, sometimes exasperatingly, exhaustingly demanding. That—and here I borrow a perfect formulation from Karen Armstrong’s memoir, The Spiral Staircase—”you have to give it your full attention, wait patiently upon it, and make an empty space for it in your mind.” That it is a demon that can pursue us as relentlessly as the Hound of Heaven. That its capacity to give is as near to infinite as anything in this world, and that what it offers us is always and inescapably in exact proportion to what we ourselves give.