A fox has a life-after-death experience.

Add a CommentViewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Channel 4, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 8 of 8

Blog: Cartoon Brew (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: CGI, Scotland, Channel 4, *Promote Video, Cartoon Brew Pick, 4mations, Axis Animation, Iain Gardner, Add a tag

Blog: Cartoon Brew (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: UK, Random Acts, Channel 4, *Promote Video, Chris Shepherd, Cartoon Brew Pick, 12Foot6, Jim Medway, Add a tag

Blog: Cartoon Brew (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Channel 4, Cartoon Brew Pick, Nexus Productions, Smith & Foulkes, Add a tag

Their world is in the grip of a lethal outbreak. A mysterious blue substance is leading to catastrophic destruction. Who is behind it all?

Add a CommentBlog: Cartoon Brew (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: UK, Dan Britt, Channel 4, *Promote Video, Cartoon Brew Pick, Add a tag

Blog: Cartoon Brew (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Channel 4, Cartoon Brew Pick, Emma Calder, Ged Haney, Lesley Bushell, Add a tag

In honoor of National Siblings Day, today's Cartoon Brew Short Pick of the Day is "The Kings of Siam."

Add a CommentBlog: Cartoon Brew (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Shorts, Jock Mooney, Random Acts, Channel 4, *Promote Video, Trunk Animation, Alasdair & Jock, Alasdair Brotherston, Barnaby Templer, James Orman, Add a tag

In their new short film, Gelato Go Home, animation directors Alasdair Brotherston & Jock Mooney shine some light on the lesser known subject of the seasonal migratory behavior of ice cream vans.

Featuring a score by James Orman and sound design by Fonic’s Barnaby Templer, the short was produced for Random Acts, the arts initiative of Channel 4, which commissions short-form creative works from both established artists and emerging talent. Gelato Go Home finds its inspiration from nature documentaries, Japanese animation and homages to animation classics like The Snowman.

“Although the film is based on a fairly absurd notion,” says Brotherston, “we really worked hard to give the film a proper sense of geography and logic to help make the ice cream vans and their journey more believable. We hope that grounding makes the film more engaging and ultimately uplifting.”

CREDITS

Directors: Alasdair Brotherston & Jock Mooney

Producer: Richard Barnett

Production Company: Trunk

3D Animation: Luca Paulli

2D Animation: Francisco Puerto Esteban, Layla Atkinson

Composer: James Orman

Sound Design & Mix: Barnaby Templer @ Fonic

Commissioner: Trunk animation in association with Lupus Films for Channel 4

Blog: Cartoon Brew (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Ideas/Commentary, Stephen Fry, TV Tropes, Channel 4, Adult Animation, Lord Reith, Marjut Rimminen, Some Protection, Add a tag

The potted history of animation’s shifting demographics should be familiar. Once, animated films were aimed at general audiences. Over time, animation began catering primarily to children. Then, more recently, animation intended for older audiences once again began to make itself known.

But the closer we look, the more intricacies we find. From Persepolis and Waltz with Bashir being discussed on the BBC’s current affairs program Newsnight, to the premiere of the late-night animated sitcom, there are countless example of adult animation bubbling up, sometimes disappearing again, other times leaving a mark.

Adult television animation developed in different ways around the world. In America, cartoons from The Simpsons to Adult Swim show that it is the ribald ethos of Ralph Bakshi and Spike and Mike’s Sick and Twisted festival which ultimately won out. The Japanese industry, meanwhile, found vast quantities of source material in the country’s multifaceted comics scene.

Sometimes it takes only a single agency to have a major impact. In Britain, adult television animation is associated primarily with Channel 4, which adopted the festival model. Throughout the Eighties and Nineties it screened countless animated shorts, mixing original commissions with work gathered from around the world.

If I were to pick a single work in which multiple streams of adult cartoons converge to great success, I would pick Some Protection, a 1987 short made by Marjut Rimminen for Channel 4. This film is based around an unscripted monologue from an incarcerated teenager named Josie O’Dwyer; the other characters with speaking roles are portrayed by actors, making the film a mixture of fact and fiction. The case of Josie O’Dwyer is abstracted into something broader, her story becoming potentially representative of any number of people with similar experiences.

Some Protection is mostly literalistic but makes use of expressionist elements. When the central character is isolated, she is placed naked against a plain white background. To show her bewildering new surroundings, there is a point of view shot swinging from one leering face to another. The film also uses symbolism in the same way as political cartoons: the outside world is portrayed as a colorful funfair, but when the protagonist escapes into it, she is immediately grabbed by the tentacle of a policeman-octopus. The imagery is not subtle, but it serves its purpose in carrying the narrative forward through a scene which would have been unwieldy if portrayed in a more literal manner.

Political cartoon, biography, social commentary, expressionism, drama, documentary – all of these elements combine in Some Protection, showing just what can be achieved once the many strains of adult animation begin to merge.

If animation was greatly affected by television, then the coming of the Internet shook things up even more. The effects of the online revolution are twofold: firstly, sites such as YouTube provide unprecedented access to animation old and new. Secondly, it has increased communication between animation viewers by providing new ways for fans to gather and share recommendations.

The Internet emerged as the ideal home for what can be termed the geek demographic, with TV Tropes being a prime example of a website put together by and for self-proclaimed geeks. The site prides itself on covering as broad a range of fiction as possible, emerging as a sometimes fascinating form of populist, open-access media scholarship. In theory, this would make it the perfect place to cover lost gems of animation, but in practice it has many blind spots. There is little discussion about Svankmajer or Norstein, while juvenile mediocrities such as Disney’s Gargoyles are treated as masterpieces on a par with the television dramas of Dennis Potter and David Simon.

TV Tropes has a page devoted to what it calls the Animation Age Ghetto, which gives a reasonable if scattershot overview of the subject. The page’s “examples” section, however, consists in large part of people filibustering about how their favorite superhero cartoons never caught on. The main reason that most of these cartoons never attracted adult audiences, of course, is that they are simply not for adults.

That’s not to say that there’s anything wrong with having guilty pleasures. The humorist Stephen Fry summed things up well: a fan of Doctor Who, he commented that “every now and again we all like a chicken nugget.” As he continued, however,

If you are an adult you want something surprising, savory, sharp, unusual, cosmopolitan, alien, challenging, complex, ambiguous, possibly even slightly disturbing and wrong. You want to try those things, because that’s what being adult means.

The ever-enthusiastic geek demographic certainly does not see animation as being merely for children. But it suffers from an inverted snobbery, with more inventive or experimental animation dismissed as “pretentious” or “arthouse”, and from a view of the medium that is built largely on nostalgia for beloved childhood cartoons. Even dedicated animation enthusiasts can overlook much of the best work which is out there: perhaps it is in human nature for audiences to stick to the films which they think they might enjoy rather than try anything new.

When commercial television first arrived in Britain in 1954 it was opposed by Lord Reith, then director-general of the publicly-funded BBC. Reith was a firm believer that television should provide quality programming which was beneficial to the public, commercial considerations and popular taste be damned. Now, with producers of online animation competing to create the crudest and most lowbrow fare, the approaches taken by festivals or outlets such as Channel 4 look rather Reithian by comparison.

Works such as Some Protection show us what adult television animation can achieve when supported by a body that is willing to back inventive and challenging creations. Just think what the broad canvas of Internet animation could achieve with a similar agency, be it a prominent funding body or a broader-minded fandom.

(Images in this post from Marjut Rimminen‘s “Some Protection”)

Add a CommentBlog: Cartoon Brew (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Ideas/Commentary, CGI, Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, Tron, Channel 4, Wreck-it Ralph, Annabel Jankel, Clare Kitson, Escape from New York, Max Headroom, Money for Nothing, Rocky Morton, Rod Lord, Add a tag

I’ve come across people who believe that Max Headroom, the Channel 4 character from the Eighties, was a genuine piece of computer animation. But although he was conceived by the animators Rocky Morton and Annabel Jankel (of Cucumber Films fame) Max himself was portrayed by actor Matt Frewer, placed into latex makeup and a shiny costume and set amidst a strange of technological tricks.

Half of the frames from the footage used in Max Headroom were removed in production, resulting in a juddery look to suggest animation shot on twos, and Frewer was bluescreened in front of a basic digital backdrop. The crew even added deliberate faults to the “animation” – such as the stammer which became Max’s trademark – to complete the effect.

This process seems somewhat surreal today, in our brave new world of Maya, Xtranormal and Blender. Max Headroom was created at a time when 3D CGI animation was desirable, but not always affordable; if the budget did not allow it, then the crew had to fake computer animation in front of the camera.

Another good example of this can be found in the 1981 film Escape from New York. Early on in the movie we see what appears to be a wireframe model of Manhattan; in actual fact, a physical model was built for this sequence, with reflective tape placed along the edges of the buildings. Shot under ultraviolet light, this recreated the luminescent green-on-black effect of primitive CGI.

There has even been an incident in which a budget imitation of CGI itself received a budget imitation. In 1987 an unidentified signal hacker managed to replace two television broadcasts with a mildly disturbing video of a home-made Max Headroom show. In this improvised effort Max was portrayed by a man in a shop-bought mask, while the moving backdrops – in the original series, an example of genuine digital animation amongst the pseudo-CGI – were replaced with somebody offscreen wiggling a bit of corrugated metal about.

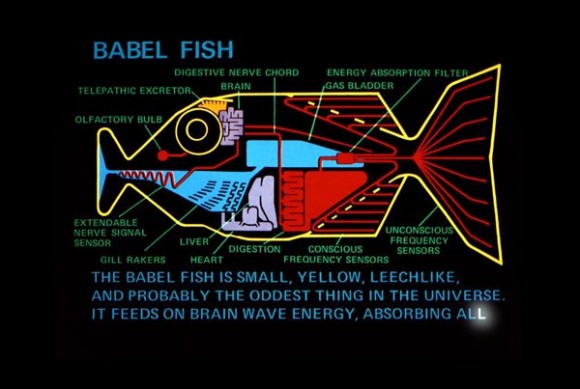

These are all extreme examples; during this period, it was more common for digital animation to be emulated using hand-drawn techniques. Often used as a visual motif in kids’ science fiction-themed cartoons (witness the cel animated wireframes in the opening sequence to Transformers) this approach was put to good use by Rod Lord‘s animation work on the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy television series from 1981. Created using litho film and coloured gels, these sequences suggested digital graphics simply by combining glowing primarily-coloured images with a black background. An added plus was that the animation could get away with being a little bit jerky…

One sequence in Hitchhiker’s Guide portrayed an intergalactic war as an early video game, a theme drawn upon by other animators: for example, in 1982 a British public information film used Space Invaders-like imagery to advise audiences on safe driving [see image below]. The biggest example of this, however, came when Disney produced an entire feature film based around the look of eighties arcade games: Tron.

Tron contained genuine CGI animation backed up with large amounts of compositing tricks based around matte effects and backlighting; this made the live action footage look as though it had been digitally processed. As a result, the film stands as arguably the premiere example of pseudo-CGI.

In her book British Animation: The Channel 4 Factor Clare Kitson remarked on the fact that Max Headroom, Channel 4’s biggest animated hit, was not actually animated. But as she went on to argue, perhaps it is time for a reappraisal:

I wonder if we might indeed classify those sequences as animation nowadays. With the plethora of different technologies now employed, the previous narrow definition (which insisted that the movement itself must be created by the animator) seems a bit old-fashioned. These days anything that appears on a screen and moves but is not a record of real life – including creatures moved by motion capture – tends to fall under the animation umbrella… The current popular synonym for animation, ‘manipulated moving image’, seems to be made for Max.

Of course, if Max had been made using actual CGI he would have ended up as a creaky old relic, rather like the “Money for Nothing” video which came out the year after his debut. Instead, Jankel, Morton and Frewer came up with a genuinely iconic creation that has aged surprisingly well.

Today, it is all too easy for animators to fall back on the tricks of their software and lose track of the wider aesthetic potential of their work. What Max Headroom—and, to an extent, some of the other pieces mentioned here—show is the opposite effect: digital animation spurring creativity in analogue work. They have an ingenuity and hand-made charm which is missing from so much modern computer animation.

Primitive digital imagery has had something of a resurgence across the past decade or so, to the point where pastiches of 8-bit pixel graphics have found their way into mainstream productions such as Wreck-It Ralph. Perhaps it is time that the animators and digital artists of today rediscovered the lesser-known cousin of this aesthetic: the strange world of pseudo-CGI.

NEIL EMMETT is the editor of The Lost Continent, a fantastic resource devoted to British animation, past and present. This piece is an expanded version of a post that originally appeared on his site.

Add a Comment