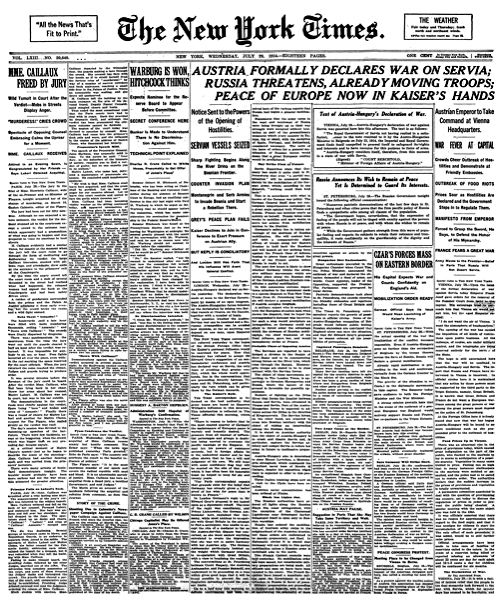

July 1914 was the month that changed the world. On 28 June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, and just five weeks later the Great Powers of Europe were at war. But how did it all happen? Historian Gordon Martel, author of The Month That Changed The World: July 1914, is blogging regularly for us over the next few weeks, giving us a week-by-week and day-by-day account of the events that led up to the First World War.

By Gordon Martel

Although Austria had declared war, begun the bombardment of Belgrade, and announced the mobilization of its army in the south, negotiations to reach a diplomatic solution continued. A peaceful outcome still seemed possible: a settlement might be negotiated directly between Austria and Russia in St Petersburg, or a conference of the four ‘disinterested’ Great Powers in either London or Berlin might mediate between Austria and Russia.

The German chancellor worried that if Sir Edward Grey succeeded in restraining Russia and France while Vienna declined to negotiate it would be disastrous; it would appear to everyone that the Austrians absolutely wanted a war. Germany would be drawn in, but Russia would be free of responsibility. ‘That would place us in an untenable situation in the eyes of our own people’. He instructed the ambassador in Vienna to advise Austria to accept Grey’s proposal.

In Vienna at 9 a.m. Berchtold convened a meeting of the common ministerial council, explaining that the Grey proposal for a conference à quatre was back on the agenda and that the German chancellor was insisting that this must be carefully considered. Bethmann Hollweg was arguing that Austria’s political prestige and military honour could be satisfied by the occupation of Belgrade and other points, while the humiliation of Serbia would weaken Russia’s position in the Balkans.

Berchtold warned that in such a conference France, Britain, and Italy were likely take Russia’s part and that Austria could not count on the support of the German ambassador in London. If everything that Austria had undertaken were to result in no more than a gain in ‘prestige’, its work would have been in vain. An occupation of Belgrade would be of no use; it was all a fraud. Russia would pose as the saviour of Serbia – which would remain intact – and in two or three years they could expect the Serbs to attack again in circumstances far less favourable to Austria. Thus, he proposed to respond courteously to the British offer while insisting on Austria’s conditions and avoiding a discussion of the merits of the case. The ministers agreed.

The British cabinet also met in the morning to consider France’s request for a promise of British intervention before Germany attacked. The cabinet divided into three factions: those who opposed intervention, those who were undecided, and those who wished to intervene. Only two ministers, Grey and Churchill, favoured intervention. Most agreed that public opinion in Britain would not support them going to war for the sake of France. But opinion might shift if Germany were to violate Belgian neutrality. Grey was instructed to request – from both Germany and France – an assurance that they would respect the neutrality of Belgium. They were not prepared to give France the promise of support that it had asked for; one of them concluded ‘that this Cabinet will not join in the war’.

Grey wired to Berlin to ask whether Germany might be willing to sound out Vienna, while he sounded out St Petersburg, on the possibility of agreeing to a revised formula that could lead to a conference. Perhaps the four disinterested Powers could offer to Austria to undertake to see that it would obtain ‘full satisfaction of her demands on Servia’ – provided that these did not impair Serbian sovereignty or the integrity of Serbian territory. Russia could then be informed by the four Powers that they would undertake to prevent Austrian demands from going to the length of impairing Serbian sovereignty and integrity. All Powers would then suspend further military operations or preparations.

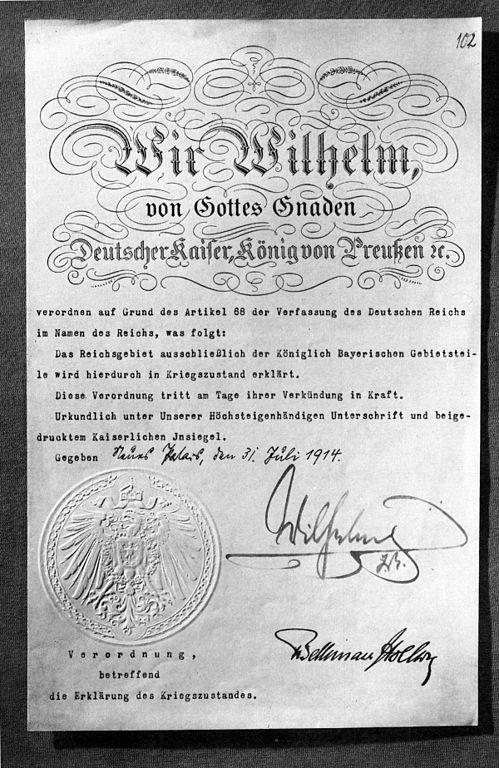

Declaration of war from the German Empire 31 July 1914. Signed by the German Kaiser Wilhelm II. Countersigned by the Reichs-Chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Germany’s response was that it could not consider such a proposal until Russia agreed to cease its mobilization. In Berlin at 2 p.m. the the drohenden Kriegszustand (‘imminent peril of war’) was announced. At 3.30 p.m. Bethmann Hollweg instructed the ambassador in St Petersburg to explain that Germany had been compelled to take this step because of Russia’s mobilization. Germany would mobilize unless Russia agreed to suspend ‘every war measure’ aimed at Austria-Hungary and Germany within twelve hours. The time clock was to begin ticking from the moment that the note was presented in St Petersburg.

At 4.15 p.m. Conrad, the chief of the Austrian general staff, telephoned the office of the general staff in Berlin to explain the Austrian position: the emperor had authorized full mobilization only in response to Russia’s actions and only for the purpose of taking precautions against a Russian attack. Austria had no intention of declaring war against Russia. In other words, Russia could mobilize along the Austrian frontier and Austria could match this on the other side. And there the two forces could wait, without going to war.

This prospect terrified Moltke. He replied immediately that Germany would probably mobilize its forces on Sunday and then commence hostilities against Russia and France. Would Austria abandon Germany? Conrad asked if Germany thus intended to launch a war against Russia and France and whether he should rule out the possibility of fighting a war against Serbia without coming to grips with Russia at the same time. Moltke told him about the ultimatums being presented in St Petersburg and Paris, which required answers by 4 p.m. the next day.

At 6.30 p.m. the Kaiser addressed a crowd of thousands gathered at the pleasure gardens in front of the imperial palace. He declared that those who envied Germany had forced him to take measures to defend the Reich. He had been forced to take up the sword but had not ceased his efforts to maintain the peace. If he did not succeed ‘we shall with God’s help wield the sword in such a way that we can sheathe it with honour’.

In London and Paris they continued to hope that a negotiated settlement was possible. Grey suggested that Russia cease its military preparations in exchange for an undertaking from the other Powers that they would seek a way to give complete satisfaction to Austria without endangering the sovereignty or territorial integrity of Serbia. Viviani, the French premier and foreign minister, agreed. He would tell Sazonov that Grey’s formula furnished a useful basis for a discussion among the Powers who sought an honourable solution to the Austro-Serbian conflict and to avert the danger of war. The formula proposed ‘is calculated equally to give satisfaction to Russia and to Austria and to provide for Serbia an acceptable means of escaping from the present difficulty’.

In St. Petersburg that evening the German ambassador, in a private audience with Tsar Nicholas, warned that Russian military measures might already have produced ‘irreparable consequences’. It was entirely possible that the decision to mobilize when the kaiser was attempting to mediate the dispute might be regarded by him as offensive – and by the German people as provocative. ‘I begged him…to check or to revoke these measures’. The Tsar replied that, for technical reasons, it was not now possible to stop the mobilization. For the sake of European peace it was essential, he argued, that Germany influence, or put pressure on, Austria.

In Paris the German ambassador was to ask the French government if it intended to remain neutral in the event of a Russo-German war. An answer was required within 18 hours. In the unlikely case that France agreed to remain neutral, France was to hand over the fortresses of Verdun and Toul as a pledge of its neutrality. The deadline by which France must agree to this demand was set for 4 p.m. the next day

In St. Petersburg, at 11 p.m., the German ambassador presented the 12-hour ultimatum to Sazonov. If Russia did not abandon its mobilization by noon Saturday Germany would mobilize in response. And, as Bethmann Hollweg had already declared, ‘mobilization means war’.

Gordon Martel is a leading authority on war, empire, and diplomacy in the modern age. His numerous publications include studies of the origins of the first and second world wars, modern imperialism, and the nature of diplomacy. A founding editor of The International History Review, he has taught at a number of Canadian universities, and has been a visiting professor or fellow in England, Ireland and Australia. Editor-in-chief of the five-volume Encyclopedia of War, he is also joint editor of the longstanding Seminar Studies in History series. His new book is The Month That Changed The World: July 1914.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The month that changed the world: Friday, 31 July 1914 appeared first on OUPblog.