I will be booktalking this one as soon as we go back to school!

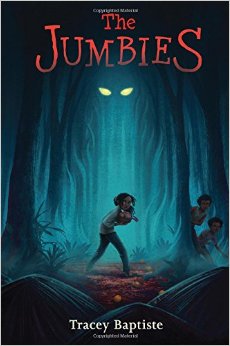

The Jumbies

The Jumbies

By Tracey Baptiste

Algonquin Young Readers

$15.95

ISBN: 9781616204143

Ages 9-12

On shelves now

“All great literature is one of two stories; a man goes on a journey or a stranger comes to town.” So sayeth Leo Tolstoy (at least in theory). Regardless of whether or not it’s actually true, it is fun to slot books into the different categories. And if I were to take Tracey Baptiste’s middle grade novel The Jumbies with the intention of designating it one type of story or another, I think I’d have to go with the latter definition. A stranger comes to town. Not quite true though, is it? For you see, in this particular book the stranger isn’t coming to town so much as infesting it. And does she still count as a stranger when she, technically was there first? It sounds a bit weird to say, “All great literature is one of two stories; a man goes on a journey or a creature comes to a village where it is the people who are the strangers” but you could make a case for that being the tale The Jumbies brings to light. Far more than just your average spooky supernatural story, Baptiste uses the underpinnings of a classic folktale to take a closer look at colonization, rebellion, and what it truly takes to share the burden of tolerating the “other”. Plus there are monsters. Gotta love the monsters.

Corinne La Mer isn’t what you might call a superstitious sort. Even when she chases an agouti into a forbidden forest she’s able to justify to herself why it looked as though a pair of yellow eyes followed her out. If she told other people about those eyes they’d say she ran across a jumbie, one of the original spooky denizens of her Caribbean island. Corinne’s a realist, though, so surely there’s another answer. And she probably would have put the whole incident out of her mind anyway, had Severine not appeared in her hut one day. Severine is beautiful and cunning. She’s been alone for a long long time and she’s in the market for a loving family. Trouble is, what Severine wants she usually gets, and Corinne may find that she and her father are getting ensnared in a dangerous creature’s loving control – whether they want to be or not. A tale based loosely on the Haitian folktale “The Magic Orange Tree.”

A bit of LOST, a bit of Beloved, and a bit of The Tempest. That’s the unusual recipe I’d concoct if I were trying to describe this book to adults. If I were trying to describe it to kids, however, I’d have some difficulty. Our nation’s library and bookstore shelves aren’t exactly overflowing with children’s novels set in the Caribbean. Actually, year or so ago I was asked to help co-create a booklist of Caribbean children’s literature with my librarian colleagues. We did pretty well in the picture book department. It was the novels that suffered in comparison. Generally speaking, if you want Caribbean middle grade novels you’d better be a fan of suffering. Whether it’s earthquakes (Serafina’s Promise), escape (Tonight By Sea), or the slave trade (My Name Is Not Angelica) Caribbean children’s literature is rarely a happy affair. And fantasy? I’m not going to say there aren’t any middle grade novels out there that make full and proper use of folklore, but none come immediately to mind. Now Ms. Baptiste debuted a decade ago with Angel’s Grace (called by Horn Book, “a promising first novel” with “An evocative setting and a focused narrative”). In the intervening ten years we hadn’t heard much from her. Fortunately The Jumbies proves she’s most certainly back in the game and with a book that has few comparable peers.

My knowledge of the Caribbean would fit in a teacup best enjoyed by a flea. What I know pretty much comes from the children’s books I read. So I am not qualified to judge The Jumbies on its accuracy to its setting or folkloric roots. When Ms. Baptiste includes what appears to be a family with roots in India in the narrative, I go along with it. Then, when the book isn’t looking, I sneak off to Wikipedia (yes, even librarians use Wikipedia from time to time) and read that “Indo-Trinidadian and Tobagonian are nationals of Trinidad and Tobago of India ancestry.” We Americans often walk around with this perception that ours is the only ethnically diverse nation. We have the gall to be surprised when we discover that other nations have multicultural (for lack of a better word) histories of their own. So it is that Corinne befriends Dru, an Indio-Trinidadian with a too large family.

The writing itself makes for a fun read. I wouldn’t label it overly descriptive or lyrical, necessarily, but it gets the job done. Besides, there are little moments in the text that I thought were rather nice. Lines like “Corinne remembered when they had buried her mama in the ground like a seed.” Or, on a creepier note, “A muddy tear spilled onto her cheek, then sprouted legs and crawled down her body.” What I really took to, more than anything else, was the central theme of “us” and “them”. Which is to say, there is no “us” and “them”, really. It’s a relationship. As a local witch says later in the story, “Our kind? What do you know about our kind and their kind, little one? You can’t even tell the difference.” Later she says it once again. “Their kind, your kind, is there a difference?” This is an island where the humans arrives and pushed out the otherworldly natives. When the natives fight back the humans are appalled. And as we read the story, we see that we are the oppressors here, to a very real extent. These jumbies might fight and hit and hurt and steal children, but they have their reasons. Even if we’ve chosen to forget what those might be.

I have a problem. I can’t read books for kids like I used to. Time was, when I first started in this business, that I could read a book like The Jumbies precisely as the author intended. I approached the material with all the wide-eyed wonder of a 10-year-old girl. Then I had to go and give birth and what happens? Suddenly I find that everything’s different and that I’m now reading the books as a parent. Scenes in The Jumbies that wouldn’t have so much as pierced my armor when I was younger now stab me directly through the heart. For example, there is a moment in this book when Dru recounts seeing her friend Allan stolen by the douens. As his mother called his name he turned to her, but his feet faced the other way, walking him into the forest. That just killed me. Kids? They’ll find it nicely creepy, but I don’t know that they’ll not entirely understand the true horror the parents encounter so that later in the book when a peace is to be reached, they have a real and active reason for continuing to pursue war. In this way the book’s final resolution almost feel too easy. You understand that the humans will agree on a peace if only because the jumbies have them outnumbered and outmanned. However, the hate and fear is going to be lingering for a long long time to come. This would be an excellent text to use to teach conflict resolution, come to think of it.

In her Author’s Note at the back of the book, Tracey Baptiste writes, “I grew up reading European fairy tales that were nothing like the Caribbean jumbie stories I listened to on my island of Trinidad. There were no jumbie fairy-tale books, though I wished there were. This story is my attempt at filling that gap in fairy-tale lore.” And fill it she does. Entrancing and engaging, frightening but never slacking, Baptiste enters an all-new folktale adaptation into our regular fantasy lore. Best suited for the kids seeking lore where creatures hide in the shadows of trees, but where they’re unlike any creatures the kids have seen before. Original. Haunting.

On shelves now.

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

Misc: Read several excerpts here.

Video:

And here’s the book trailer for you:

The Walls Around Us by Nova Ren Suma. Algonquin Young Readers. 2015. Reviewed from electronic galley.

SO TRUE about parenthood changing one’s experience of books. (A lot of people say it’s adulthood that does that. I don’t think so. I think it’s worrying intensely — even when you’re trying your best to be chill — about the emotional experiences of your offspring.) I was shocked when I revisited Harriet the Spy as a parent; it was agonizing for me in its depiction of blithe parental selfishness and cruelty, the intensity of Harriet’s feelings for Golly and the calculating meanness of other kids. But my daughter, listening to me read, had the same experience of it as I had when I was a kid: Ooh, exciting! And awful and completely understandable and delightful!

I am floored by this review. Thank you.

I read this one aloud to my girls. We all enjoyed it so much. It’s been our most memorable read-aloud thus far this year, definitely. (And tomorrow at Kirkus I chat with Tracey about it, FYI.)

The parent-reader-worry-wart-syndrome issue reminds me of a conversation I had years ago. With my oldest. She was reading THE THIRTEEN CLOCKS and told me very seriously that I was not allowed to read it.

“Why not?” I asked her.

“It’s too scary for you,” she said. She was seven at the time.

“Well,” I said. “Isn’t it too scary for you”?

“Of course not. Kids are braver than grownups. Everyone knows that.”

I think it’s good for the gatekeepers of the world to remember that from time to time.