Copyright 2009, Carol Baicker-McKee

Cost of One Piece Original Art by Carol Baicker-McKee from An Apple Pie for Dinner by Susan vanHecke (Marshall Cavendish, Fall, 2009)

Testing for:

Foamcore for backing and supports $100

Mat board for support $100

Chenille stems (metal plus fabric) $200

3 colors of acrylic paint $300

13 colors of polymer clay $1300

12 different fabrics $1200

5 different threads and floss $500

4 different textile trims $400

Polyester batting $100

Metallic powder $100

2 colors pastels $200

Labor, artistry $500

Total: $5,000

Cost of destroying my one of a kind artwork so I can sell it: Priceless

My mixed media artwork is undeniably more complex, with many more components than most illustrators' work (the above photo is of a much simpler book in progress, and you can see there are lots of parts), but non-artists would still be shocked to break down the components in even a typical painting. Plus the parts of a frame. But either way, illustrators who want to sell their artwork on the open market, especially if like me they haven't yet achieved the level of fame and fortune that would allow their work to be classified as "collectible" (and thus not intended for use in a children's bedroom) are probably in deep doo-doo under CPSIA. My estimate above of the testing costs is surely a low ball figure, as I used only $100 per component and I know that's low, and I've undoubtedly overlooked a few pieces to boot. Unframed, testing costs would drive up the price to 10 times what I'd guess would be a top, top make-me-very happy price for that piece. Framing would add a couple hundred dollars more. And then there's the wee final problem: I'd have nothing left to sell after I got it tested.

When I spoke with Joe Martyak, the Chief of Staff at CPSC, for information for my article for the Society of Children's Book Writers and Illustrators (SCBWI), he initially seemed bewildered about my questions about original artwork and CPSIA; he didn't seem to think wall artwork was covered. When I said I'd read several documents from CPSC that specifically mentioned posters and other wall decor, he hemmed and hawed, and said, well, if it was intended for a child's room, it probably would be. Then he said art wouldn't be considered accessible once it was framed. I said, "How is art protected by a piece of fragile glass on one side and a thin piece of cardboard on the other less accessible than the inside of a bike tire valve stem? And how does an artist judge what is "normal use and abuse" for a framed picture? Because if it includes throwing something that knocks it off the wall, it could certainly become accessible, though of course the broken glass might be a more immediate worry." I also asked about the problem of testing one of a kind items (known among the crafty set as OOAK items). At that point, he decided he'd have to get back to me about original art.

Of course he hasn't yet, and I don't blame him; among the millions of details the CPSC has to sort through and rule on, questions about original art surely rank very low - unless you're an artist creating work that would be bought for kids and you'd like to keep earning a living. (Or in my case, would also like to clear a little shelf space to accommodate all the other bulky art work you're producing.)

This piece is a very simple one, one of several I made at my publisher's request as promotional giveaways to promote one of my books (Merry Christmas, Cheeps! by Julie Stiegemeyer, Bloomsbury, 2007). Paying to test it would of course be foolish on many fronts, but even a small simple piece like this has an insane number of components (at least 22 by my quick count), thus putting an end to cool promotional items. These matter because buyers for book chains base their orders on initial buzz for the book at BEA and other venues - and special promotional tactics get attention.

The photos above and below are of a piece I made for a charity,

Robert's Snow, that raises funds for cancer research. The event honors the husband of the enormously talented and well-loved children's book author and illustrator

Grace Lin, who was stricken with a rare cancer. Children's book illustrators are invited to create artwork on wooden snowflakes which are then auctioned. Again, mine is probably more complex than most, but many others are incredible 3-D creations too. (And little did I realize by adding a box intended for long term storage I'd be adding to the components in need of testing.) Some of the snowflakes by top illustrators fetch collectible level prices, but others are not out of question for hanging in a child's room. It's yet another very gray area under CPSIA, surely not one that anyone intended, but one that looms ominously over people trying to do a good thing nonetheless.

If you have a few more minutes, go check out

this post at Deputy Headmistress's

The Common Room. She finally found someone to kind of debate the merits (or at least intentions) of CPSIA with her. PJFry via BoingBoing mentions a number of the misconceptions about lead in books, and Deputy Headmistress walks her through the science and real-life reasons why they're wrong.

All images copyright Carol Baicker-McKee, 2008

Next to the moment when you hold the first published copy of your book in your hand, there's nothing quite like the moment when the proofs arrive. Seeing the words and the completed art together, getting to turn the pages and have the experience of "book" is magical every time. It really is like the cliche - akin to examining your newborn's tiny fingernails and smelling its delicious newness.

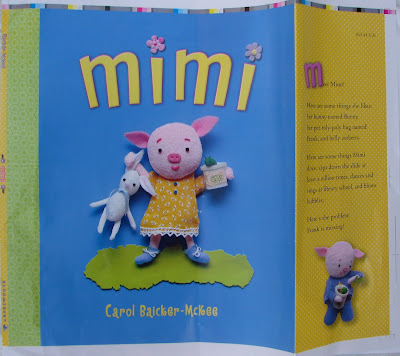

Anyhow, here are a few images from Mimi, the first book I wrote and illustrated. It's due out June 24th from Bloomsbury. I feel jumping up and down proud of it, so much so that I had to stick some of the pictures up now even though my scanner still won't work, and I have to settle for posting crappy photos of un-color-corrected proofs.

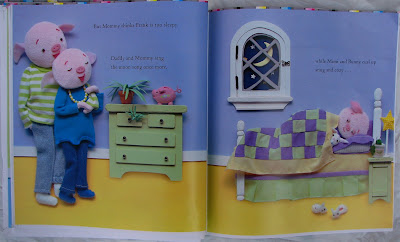

Mimi is her own "person," but there's no denying her character sprouted from my memories of my daughter Sara when she was that age. Sara's now 16 - so grown up these days that she even assisted with the artwork! For instance, she made the little flowers that dot the "i's" on the cover, helped me paint backgrounds (she's a much better painter than I am - any place you see brushstrokes: my fault), strung the beads for Mom's necklaces, made the spider plant on Mimi's dresser, and did other odds and ends for me. It was lots of fun to work together - and good for our relationship during the sometimes (okay, often) squabbly menopausal mom/hormonal teen daughter years.

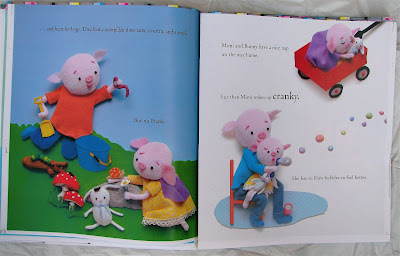

The story and illustrations are peppered with details from Sara's toddler days, from her fashion sense to the arched window in her bedroom. Other details are from my other kids (my son Kyle had a pet roly poly, and Eric was glued to his stuffed Ted-Ted), and even from chance kid encounters (Mimi's jammies-and-tutu outfit was prompted by a little girl I saw similarly attired at the grocery store). At conferences, it seems like editors and agents are always saying they don't want to hear how your story or art is based on your own kids, etc., etc. - but don't let that fool you into thinking you should ignore the material from your own relationships and experiences while you're creating your work. Those personal bits and pieces are what let writers and illustrators create characters and a story world that are simultaneously quirky and universal - that feel authentic, because they are. It's just that it's important to stay flexible and not get too attached to any one "real" thing - often the story will need you to change or leave out something that feels so special to you, and you just have to be tough and do it. "Kill your darlings" as some author, I forget who, said.

I can't look at the proofs without being reminded of all the things I struggled with in making the illustrations. Some things I figured out more-or-less successfully - like how to get the perspective right for the wagon - and others the designer, Daniel Roode, has painstakingly corrected for me. For example: the bubbles. (Sorry Daniel!) I had a terrible time deciding how to make them. Having learned the hard way from the illustrations for Merry Christmas, Cheeps by Julie Stiegemeyer that it's a bad idea to incorporate shiny things in my 3-D artwork - the reflections are a huge headache for the photographer and the designer too - I knew to avoid all the things like marbles, hollow glass balls, iridescent beads, etc. that sorely tempted me, but I didn't think through the implications of using solid balls made from Sculpey Ultralight clay and positioning them at different heights off the background with bits of foam core. I thought they'd have depth and the sense of floating in the air, but instead all they had was really dark, bizarre-looking shadows! I can't imagine what a headache it must have been to photoshop all those shadows away - especially since the page after the one shown above is almost all bubbles. But they look fantastic now - just like they're floating. Next time I'll glue something like that down.

I'm also incredibly grateful to my editor, Melanie Cecka, who truly deserves the adjective "brilliant." She can edit an already spare text down to the nub - leaving only the best bits to shine in their simplicity. The other day I looked over my first draft of this story (well, the one I submitted), and I couldn't believe how rambly and unfocused it felt. I'm so glad that Melanie was able to see the core of it, and to gently coax me to pare away until I found it too.

I'd love to hear reactions to Mimi - I feel like a first time mama wanting everyone to admire her beautiful baby (that probably really looks like an extra-wrinkly Yoda). And if you have any great ideas for making 3-D bubbles that photograph well, I'd love to hear about it, in case I'm struck by temporary insanity and decide to put them in another book.