new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: 2013 middle grade fiction, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 6 of 6

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: 2013 middle grade fiction in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 1/1/2014

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

middle grade historical fiction,

multicultural middle grade,

Krista Russell,

African-American kids,

Best Books of 2013,

2013 middle grade fiction,

2013 historical fiction,

African-American books,

multicultural,

Reviews,

middle grade fiction,

slavery,

multicultural fiction,

African-American history,

Add a tag

The Other Side of Free

The Other Side of Free

By Krista Russell

Peachtree Publishers

$16.95

ISBN: 978-1-56145-710-6

Ages 9-12

On shelves now

Have you ever read the adult book How I Became a Famous Novelist? Bear with me for a second here, I know what I’m doing. You see, in the title the author decides that he wants to become a New York Times bestseller. In the course of his quest he runs across a variety of different authors who embody a variety of different types of novels. His own aunt decides she wants to be a children’s author and sets about doing so by writing a work of historical middle grade fiction. The book is about a girl living in Colonial America who wants to be a cooper. In only a page or two author Steve Hely puts his finger on a whole swath of children’s books that drive librarians like myself mildly mad. They find familiar situations and alter very little aside from location and exact year to tell their tales. The result is an increasing wariness on my part to read any works of historical fiction, for fear that you’ll see the same dang story again and again. With all this in mind you can imagine the relief with which I read Krista Russell’sThe Other Side of Free. Not only is the setting utterly original (not to mention unforgettable) but the characters don’t fill the same little roles you’ll see in other children’s novels. If you have kids that have tired of the same old, same old, The Other Side of Free will give them something they haven’t seen before.

We’ve all heard of how slaves would escape to the North when they wished to escape for good. But travel a bit farther back in time to the early 18th century and the tale is a little different. At that point in history slaves didn’t flee north but south to Spain’s territories. There, the Spanish king promised freedom for those slaves that swore fidelity to the Spanish crown and fought on his behalf against the English. 13-year-old Jem is one of those escaped slaves, but his life at Fort Mose is hardly stimulating. Kept under the yoke of a hard woman named Phaedra, Jem longs to fight for the king and to join in the battles. But when at last the fighting comes to him, it isn’t at all what he thought it would be. A Bibliography of sources appears at the end of the book.

There are big themes at work here. What freedom is worth to an individual if it means yoking yourself to someone else. If militia work really does mean freedom, or just slavery of a new kind. Jem himself chafes under the hand of Phaedra, though I think it would be obvious, even to a kid reader, that he’s immature in more than one way. But with all that said, it’s the lighter moments that make the book for me. Omen the owl is a notable example of a detail that makes the book more than just a work of history. In this story Jem adopts an owlet and raises it as his own. In your standard generic fare the owl would be a beloved friend and companion, possibly ultimately dying for Jem in a heroic scene reminiscent of Hedwig’s death. Instead, the owl is hell on wings. A nasty, chicken-snatching, very real and wild creature that is, nonetheless, beloved of our hero. Again, expectations are upset. I love it when that happens.

I liked the individual lines Russell used to dot the text as well. For example, in an early character note about Phaedra the book describes her construction of a grass basket. “Her fingers snatched at the fronds again and again, until each strip was bent and shaped to her will.” It’s worth noting that it’s Jem who is saying this about her. Almost the whole book is told through his own perspective and, as such, may not be entirely trustworthy. He has his own prejudices to fight, after all. I also like Russell’s everyday descriptions. “Adine handed each man a jug of water. They drank until it ran down their faces, leaving tails like gray veins down their throats.” Beautifully put.

Honestly it would make a heckuva stage play. The settings are necessarily limited, with Jem spending most of his time in Fort Mose and the rest of it in St. Augustine. Not having been familiar with the people of Fort Mose before, I found myself incredibly anxious to learn what became of them. Russell ends the book on a hopeful note, but you cannot help but wonder. If there were freed slaves in Florida in 1739 then what happened when that state became the property of the English in 1763? All Russell says at that time is “At this time, the free Africans of Mose relocated to Cuba.” Kids will just have to extrapolate a happy ending for Jem and his friends from that.

A great work of historical fiction does a number of things. It introduces you to unfamiliar places and people. It establishes a kind of empathy for those people that you otherwise would never have met. It puts you in their shoes, if only for a moment. And most of all, it surprises you. Upsets your expectations, maybe. For most kids in America, the history of slavery is short and sweet. Slaves came from Africa. They escaped North. They were freed thanks in part to the Civil War. What more is there is say or to learn aside from some vague info on the Underground Railroad? Russell challenges these assumptions, bringing us a tale that is wholly new, but filled with facts. If the rote and familiar don’t suit you and you want a book that travels over new ground, you can hardly do better than The Other Side of Free. Smart and original, it’s a one-of-a-kind novel. Hardly the kind of thing you run across every day.

On shelves now.

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

Notes on the Cover: I don’t want to sound ungrateful. I can see what Peachtree was going for here. In this image you get the dense canopy of a Floridian forest. You even have a black boy on the cover (albeit completely turned away from the viewer, which is kind of a cheat). But all in all, whether it’s the art or the design or the color palette, this book is not the most visually appealing little number I’ve seen in all my livelong days. I’m having a devil of a time getting folks to pick it up of their own accord. One hopes that if it goes to paperback someday, maybe it’ll be given a cover worthy of its content.

Like This? Then Try:

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 12/4/2013

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reviews,

middle grade fiction,

historical fiction,

Random House,

Rosanne Parry,

middle grade historical fiction,

multicultural middle grade,

Best Books of 2013,

2013 reviews,

2013 middle grade fiction,

2013 historical fiction,

Add a tag

Written in Stone

Written in Stone

By Rosanne Parry

Random House

$16.99

ISBN: 978-0-375-86971-6

Ages 9-12

On shelves now

Finding books of historical fiction for kids about Native Americans is an oddly limited proposition. Basically, it boils down to Pilgrims, the Trail of Tears, the occasional 1900s storyline (thank God for Louise Erdrich), and . . . yeah, that’s about it. Contemporary fiction? Unheard of at best, offensive at worst. Authors, it seems, like to relegate their American Indians to the distant past where we can feel bad about them through the conscience assuaging veil of history. Maybe that’s part of what I like so much about Rosanne Parry’s Written in Stone. Set in the 1920s, Parry picks a moment in time with cultural significance not for the white readers with their limited historical knowledge but for the people most influenced by changes both at home and at sea. Smart and subtle by turns, Parry tackles a tricky subject and comes away swinging.

A girl with a dream is just that. A dreamer. And though Pearl has always longed to hunt whales like her father before her, harpooning is not in her future. When her father, a member of the Makah people of the Pacific Northwest, is killed on a routine hunt, Pearl’s future is in serious doubt. Not particularly endowed with any useful skills (though she’d love to learn to weave, if anyone was around to teach her), Pearl uncovers on her own a series of forgotten petroglyphs and the plot of a nefarious “art dealer”. Now her newfound love of the written word is going to give her the power to do something she never thought possible: preserve her tribe’s culture.

It’s sort of nice to read a book and feel like a kid in terms of the plot twists. Take, for example, the character of the “collector” who arrives and then immediately appears to be something else entirely. I probably should have been able to figure out his real occupation (or at least interests) long before the book revealed them to me, and yet here I was, toddling through, not a care in the world. I never saw it coming, and that means that at least 75% of the kids reading this book will also be in for a surprise.

I consider the ending of the book a bit of a plot twist as well, actually. We’re so used to our heroes and heroines at the ends of books pulling off these massive escapades and solutions to their problems that when I read Pearl’s very practical and real world answer to the dilemma posed by the smooth talking art dealer I was a bit taken aback. What, no media frenzied conclusion? No huge explosions or public shaming of the villain or anything similarly crass and confused? It took a little getting used to but once I’d accepted the quiet, realistic ending I realized it was better (and more appropriate to the general tone of the book) than anything a more ludicrous premise would have allowed.

If anything didn’t quite work for me, I guess it was the whole “Written in Stone” part. I understood why Pearl had to see the petroglyphs so as to aid her own personal growth and understanding of herself as a writer. That I got. It was more a problem that I had a great deal of difficulty picturing them in my own mind. I had to do a little online research of my own to get a sense of what they looked like, and even that proved insufficient since Parry’s petroglyphs are her own creation and not quite like anything else out there. It’s not an illustrated novel, but a few choice pen and inks of the images in their simplest forms would not have been out of place.

Now let us give thanks to authors (and their publishers) that know the value of a good chunk of backmatter. 19 pages worth of the stuff, no less (and on a 196-page title, that ain’t small potatoes). Because she is a white author writing about a distinct tribal group and their past, Parry treads carefully. Her extensive Author’s Note consists of her own personal connections to the Quinaults, her care to not replicate anything that is not for public consumption, the history of whaling amongst the Makah people, thoughts on the potlatch, petroglyphs, a history of epidemics and economic change to the region (I was unaware that it was returning WWI soldiers with influenza that were responsible for a vast number of deaths to the tribal communities of the Pacific Northwest at that time), the history of art collectors and natural resource management, an extensive bibliography that is split between resources for young readers, exhibits of Pacific Northwest art and artifacts, and resources for older readers, a Glossary of Quinault terms (with a long explanation of how it was recorded over the years), and a thank you to the many people who helped contribute to this book. PHEW! They hardly make ‘em like THIS these days.

I also love the care with which Parry approached her subject matter. There isn’t any of this swagger or ownership at work that you might find in other authors’ works. Her respect shines through. In a section labeled “Culture and Respect” Parry writes, “Historical fiction can never be taken lightly, and stories involving Native Americans are particularly delicate, as the author, whether Native or not, must walk the line between illuminating the life of the characters as fully as possible and withholding cultural information not intended for the public or specific stories that are the property of an individual, family, or tribe.” In this way the author explains that she purposefully left out the rituals that surround a whale hunt. She only alludes to stories of the Pitch Woman and the Timber Giant, never giving away their details. She even makes note the changes in names and spellings in the 1920s versus today.

I don’t know that you’re going to find another book out there quite like Written in Stone. Heck, I haven’t even touched on Pearl’s personality or her personal connections to her father and aunt. I haven’t talked about my favorite part of the book where Pearl’s grandfather haggles with a white trading partner and gets his wife to sing a lullaby that he claims is an ancient Indian curse. I haven’t done any of that, and yet I don’t think that there’s much more to say. The book is a smart historical work of fiction that requires use of the child reader’s brain more than anything else. It’s a glimpse of history I’ve not seen in a work of middle grade fiction before and I’d betcha bottom dollar I might never see it replicated again. Hats off then to Ms. Parry for the time, and effort, and consideration, and care she poured into this work. Hats off too to her editor for allowing her to do so. The book’s a keeper, no question. It’s just a question of finding it, is all.

On shelves now.

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

Notes on the Cover: This marks the second Richard Tuschman book jacket I’ve reviewed this year. The first was A Girl Called Problem, one of my favorites of 2013. The man has good taste in books.

Other Reviews:

Professional Reviews:

Misc:

Videos: Um . . . okay, I sort of love this fan made faux movie trailer for the book. It’s sort of awesome. Check it out.

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 9/26/2013

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Best Books,

Anne Ursu,

Best Books of 2013,

Reviews 2013,

2013 reviews,

2013 middle grade fiction,

2014 Newbery contenders,

2013 chapter books,

2013 fantasy,

Reviews,

middle grade fiction,

fantasy,

middle grade fantasy,

Add a tag

The Real Boy

The Real Boy

By Anne Ursu

Illustrated by Erin McGuire

Walden Pond Press (an imprint of Harper Collins)

$16.99

ISBN: 978-0-06-201507-5

Ages 9-12

On shelves now

My two-year-old is dealing with the concept of personhood. Lately she’s taken to proclaiming proudly “I’m a person!” when she has successfully mastered something. By the same token, failure to accomplish even the most mundane task is met with a dejected, “I’m not a person”. This notion of personhood and what it takes to either be a person or not a person reminded me a fair amount of Anne Ursu’s latest middle grade novel The Real Boy. There aren’t many children’s books that dare to delve into the notion of what it means to be a “real” person. Whole hosts of kids walk through their schools looking around, wondering why they aren’t like the others. There’s this feeling often that maybe they were made incorrectly, or that everyone else is having fun without them because they’re privy to some hitherto unknown secret. Part of what I love about Anne Ursu’s latest is that it taps directly into that fear, creating a character that must use his wits to defeat not only the foes that beset him physically, but the ones in his own head that make even casual interactions a difficulty.

Oscar should be very grateful. It’s not every orphan who gets selected to aid a magician as talented as Master Caleb. For years Oscar has ground herbs for Caleb, studiously avoiding the customers that come for his charms, as well as Caleb’s nasty apprentice Wolf. Oscar is the kind of kid who’d rather pore over his master’s old books rather than deal with the frightening conversations a day in his master’s shop might entail. All that changes the day Wolf meets with an accident and Caleb starts leaving the shop more and more. A creature has been spotted causing awful havoc and the local magic workers should be the ones to take care of the problem. So why aren’t they? When Oscar is saved from the role of customer service by an apprentice named Callie, the two strike up an unlikely friendship and seek to find not just the source of the disturbance but also the reason why some of the rich children in the nearby city have been struck by the strangest of diseases.

Though Ms. Ursu has been around for years, only recently have her books been attracting serious critical buzz. I was particularly drawn to her novel retelling of Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Snow Queen” last year in the form of the middle grade novel Breadcrumbs. So naturally, when I read the plot description and title of The Real Boy I assumed that the story would be some kind of retelling of the “Pinocchio” tale. As it turns out, there is the faintest whiff of Pinocchio circling this story, but it is by no means a strict model. As one of the librarians in my system put it, “I am scarred for life by Pinocchio (absolutely abhor any tale relating to inanimate objects longing to become real to the point where I find it creepy) but did not find this disturbing in the least.” Truth be told it would have been easy enough for Ursu to crank up the creepy factor if she had wanted to. But rather than clutter the text up with unnecessary disgust, the story is instead clean, fast, exciting, and to the point. And for all that it is 352 pages or so, you couldn’t cut it down.

There have been a fair number of novels and books for children this year that have been accused of being written with adults rather than children in mind. I’ve fielded concerns about everything from Bob Graham’s The Silver Button to Cynthia Rylant’s God Got a Dog to Sharon Creech’s The Boy on the Porch. Interestingly, folks have not lobbed the same criticisms at The Real Boy, for which I am grateful. Certainly it would be easy to see the title in that light. Much of the storyline hinges on the power of parental fear, the sometimes horrific lengths those same parents will go to to “protect” their young, and the people who prey on those fears. Parents, teachers, and librarians that read this book will immediately recognize the villainy at work here, but kids will perceive it on an entirely different level. While the adults gnash their teeth at the bad guy’s actions, children will understand that the biggest villain in this book isn’t a person, but Oscar’s own perceptions of himself. To defeat the big bad, our hero has to delve deep down into his own self and past, make a couple incorrect assumptions, and come out stronger in the end.

He is helped in no small part by Callie. I feel bad that when in trying to define a book I feel myself falling back on what it doesn’t do rather than what it does do. Still, I think it worth noting that in the case of Callie she isn’t some deux ex machina who solves all of Oscar’s problems for him. She helps him, certainly. Even gets angry and impatient with him on occasion, but she’s a real person with a personal journey of her own. She isn’t just slapped into the narrative to give our hero a necessary foil. The same could be said of the baker, a fatherly figure who runs the risk of becoming that wise adult character that steps in when the child characters are flailing about. Ursu almost makes a pointed refusal to go to him for help, though. It’s as if he’s just there to show that not all adults in the world are completely off their rockers. Just most, it would seem.

There’s one more thing the book doesn’t do that really won my admiration, but I think that by even mentioning it here I’m giving away an essential plot point. Consider this your official spoiler alert, then. If you have any desire to read this book on your own, please do yourself a favor and skip this paragraph. All gone? Good. Now a pet peeve of mine that I see from time to time and think an awfully bad idea is when a character appears to be on the autism spectrum of some sort, and then a magical reason for that outsider status comes up. One such fantasy I read long ago, the autistic child turned out to be a fairy changeling, which explained why she was unable to communicate with other people. While well intentioned, I think this kind of plot device misses the point. Now one could make the case for Oscar as someone who is on “the spectrum”. However, the advantage of having such a character in a fantasy setting is that there’s no real way to define his status. Then, late in the book, Oscar stumbles upon a discovery that gives him a definite impression that he is not a human like the people around him. Ursu’s very definite choice to then rescind that possibility hammered home for me the essential theme of the book. There are no easy choices within these pages. Just very real souls trying their best to live the lives they want, free from impediments inside or outside their very own selves.

I’ve heard a smattering of objections to the book at this point that are probably worth looking into. One librarian of my acquaintance expressed some concern about Ursu’s world building. She said that for all that she plumbs the depths of character and narrative with an admirable and enviable skill, they never really felt that they could “see” the world that she had conjured. I suspect that some of this difficulty might have come from the fact that the librarian read an advanced reader’s copy of the book without the benefit of the map of Aletheia in the front. But maybe their problem was bigger than simple geography. Insofar as Ms. Ursu does indulge in world building, it’s a world within set, tight parameters. The country is an island with a protected glittering city on the one hand and a rough rural village on the other. Much like a stage play, Ursu’s storyline is constricted within the rules she’s set for herself. For readers who prefer the wide all-encompassing lands you’d see in a Tolkien or Rowling title, the limitations might feel restrictive.

Now let us not, in the midst of all this talky talk, downplay the importance of illustrator Erin McGuire. McGuire and Ursu were actually paired together once before on the underappreciated Breadcrumbs. I had originally read the book in a form without the art, and it was pleasant in and of itself. McGuire’s interstitial illustrations, however, really serve to heighten the reader’s enjoyment. The pictures are actually relatively rare, their occasional appearances feeling like nothing so much as a delicious chocolate chip popping up in a sea of vanilla ice cream. You never know when you’ll find one, but it’s always sweet when you do.

Breadcrumbs, for all that I personally loved it, was a difficult book for a lot of folks to swallow. In it, Ursu managed to synthesize the soul-crushing loneliness of Hans Christian Andersen’s tales, and the results proved too dark for some readers. With The Real Boy the source material, if you can even call it that, is incidental. As with all good fantasies for kids there’s also a fair amount of darkness here, but it’s far less heavy and there’s also an introspective undercurrent that by some miracle actually appears to be interesting to kids. Whodathunkit? Wholly unexpected with plot twists and turns you won’t see coming, no matter how hard you squint, Ursu’s is a book worth nabbing for your own sweet self. Grab that puppy up.

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 5/2/2013

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

multicultural,

mysteries,

Reviews,

middle grade fiction,

historical fiction,

Best Books,

Eerdmans Books for Young Readers,

multicultural fiction,

middle grade mysteries,

middle grade historical fiction,

multicultural middle grade,

Best Books of 2013,

Reviews 2013,

2013 reviews,

2013 middle grade fiction,

2013 chapter books,

2013 historical fiction,

2013 mysteries,

Katie Quirk,

Add a tag

A Girl Called Problem

A Girl Called Problem

By Katie Quirk

Eerdmans Books for Young Readers

$8.00

ISBN: 97800-8028-5404-9

Ages 9-12

On shelves now.

Who says that mystery novels for kids all have to include the same tropes and settings? I tell you, half the time when a kid comes up to a reference desk asking for a mystery they think what they want is the standard white kids in suburbia model perfected by Encyclopedia Brown and his ilk. They’re wrong. What they really want is great writing and a good mystery with a twist they don’t see coming. So I will hereby give grand kudos and heaping helpfuls of praise to the librarian/bookseller/parent who hears a kid ask for a mystery and hands them Katie Quirk’s A Girl Called Problem. This book is a trifecta of publishing rarities. A historical novel that is also a mystery set in a foreign country that just happens to be Tanzania. Trust me when I say your shelves aren’t exactly filled to brimming with such books. Would that they were, or at the very least, would that you had as many good books as this one. Smart commentary, an honestly interesting storyline, and sharp writing from start to finish, Quirk quickly establishes herself as one author to watch.

The thing about Shida is that in spite of her name (in Swahili it would be “problem”) you just can’t get her down. Sure, her mom is considered a witch, and every day she seems to make Shida’s life harder rather than easier. Still, Shida’s got dreams. She hopes to someday train to be a healer in her village of Litongo, and maybe even a village nurse. In light of all this, when the opportunity arises for all of Litongo to pick up and move to a new location, Shida’s on board with the plan. In Nija Panda she would be able to go to school and maybe even learn medicine firsthand. Her fellow villagers are wary but game. They seem to have more to gain than to lose from such a move. However, that’s before things start to go terribly wrong. Escaped cattle. Disease. Even death seems to await them in Nija Panda. Is the village truly cursed, just unlucky, or is there someone causing all these troubles? Someone who doesn’t want the people of Litongo there. Someone who will do anything at all to turn them back. It’s certainly possible and it’s up to Shida to figure out who the culprit might be.

The trouble with being an adult and reading a children’s work of mystery fiction is that too often the answer feels like it’s too obvious. Fortunately for me, I’m terrible at mysteries. I’ll swallow every last red herring and every false clue used by the author to lead me astray. So while at first it seems perfectly obvious who the bad guys would be, I confess that when the switcheroo took place I didn’t see it coming. It made perfect sense, of course, but I was as blindsided as our plucky heroine. I figure if I honestly as a 35-year-old adult can’t figure out the good guys from the bad in a book for kids, at least a significant chunk of child readers will be in the same boat.

Now I’ve a pet peeve regarding books set in Africa, particularly historical Africa, and I was keen to see whether or not Ms. Quirk would indulge it. You see, the story of a girl in a historical setting who wants to be a healer but can’t because of her gender is not a particularly new trope. We’ve seen it before, to a certain extent. What chaps my hide is when the author starts implying that tribal medicines and healing techniques are superstitious and outdated while modern medicine is significantly superior. Usually the heroine will fight against society’s prejudices, something will happen late in the game, and the villagers will see that she was right all along and that she’ll soon be able to use Western medicine to cure all ills. There’s something particularly galling about storylines of this sort, so imagine my surprise when I discovered that Quirk was not going to fall into that more than vaguely insulting mindset. Here is an author unafraid to pay some respect to the religion of the villagers. It never dismisses curses but acknowledges them alongside standard diseases. Example: “Though Shida was certain Furaha should take medicine for malaria, she was equally certain she should guard the spirit house that night. Parasites were responsible for some sicknesses and curses for others, and in this case, they needed to protect against both.”

Quirk is also quite adept at using the middle grade chapter book format to tackle some pretty complex issues. To an adult reading this book it might be clear that Shida’s mother suffers from a severe form of depression. There’s no way the village would be prepared to handle this diagnosis, and Shida herself just grows angry with the woman who stays inside all the time. You could get a very interesting book discussion going with child readers about whether or not Shida should really blame her mother as vehemently as she does. On the one hand, you can see her point. On the other, her mother is clearly in pain. Similarly well done is the final discussion of witches. Quirk brings up a very sophisticated conversation wherein Shida comes to understand that accused witches are very often widows who must work to keep themselves alive and that, through these efforts, acquire supposedly witchy attributes. Quirk never hits you over the head with these thoughts. She just lets her heroine’s assumptions fall in the face of close and careful observation.

All this could be true, but without caring about the characters it wouldn’t be worth much. I think part of the reason I like the book as much as I do is that everyone has three dimensions (with the occasional rare exception). Even the revealed villain turns out to have a backstory that explains their impetus, though it doesn’t excuse their actions. As for Shida herself, she may be positive but she’s no Pollyanna. Depression hits her hard sometimes too, but through it all she uses her brain. Because she is able to apply what she learns in school to the real world, she’s capable of following the clues and tracking down the real culprit behind everyone’s troubles. Passive protagonists have no place in A Girl Called Problem. No place at all.

Finally, in an era of Common Core Standards I cannot help but notice how much a kid can learn about Tanzania from this book. Historical Tanzania at that! A Glossary at the back does a very good job of explaining everything from flamboyant trees to n’gombe to President Julius Nyerere’s plan for Tanzania. There are also photographs mixed into the Glossary that do a good job of giving a contemporary spin on a historical work.

Windows and mirrors. That’s the phrase used by children’s literature professionals to explain what we look for in books for kids. We want them to have books that reflect their own experiences and observations (mirrors) and we also want them to have books that reflect the experiences and observations of kids living in very different circumstances (windows). Mirror books can be a lot easier to recommend to kids than window books, but that just means you need to try harder. So next time a 9-12 year-old comes to you begging for a mystery, upset their expectations. Hand them A Girl Called Problem and bet them they won’t be able to guess the bad guy. In the process, you might just be able to introduce that kid to their latest favorite book.

On shelves now.

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

Notes on the Cover: Now was that so hard? We ask and we ask and we ask for brown faces on our middle grade fiction and still it feels like pulling teeth to get it done. Eerdmans really blew this one out of the water, and it seems they spared no expense. The book jacket is the brainchild of Richard Tuschman who you may know better as the man behind the cover of Claire Vanderpool’s Newbery Award winning Moon Over Manifest. Beautiful.

Other Blog Reviews: Loganberryblog

Professional Reviews: A star from Kirkus

Misc:

- This is utterly fascinating. In this post author Katie Quirk talks about the process that led to the current (and truly lovely) cover.

- And Ms. Quirk shares what a typical day for Shida might look like in this video.

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 3/18/2013

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

science fiction,

Reviews,

middle grade fiction,

Best Books,

Bloomsbury,

Walker Books for Young Readers,

middle grade science-fiction,

Jim Kay,

Best Books of 2013,

Reviews 2013,

2013 reviews,

2013 middle grade fiction,

2014 Newbery contenders,

2013 chapter books,

2013 science fiction,

Megan Frazer Blakemore,

Add a tag

The Water Castle

The Water Castle

By Megan Frazer Blakemore

Illustrated by Jim Kay

Walker Books for Young Readers (an imprint of Bloomsbury)

$16.99

ISBN: 978-0-8027-2839-5

Ages 9-12

On shelves now

Where does fantasy stop and science fiction begin? Is it possible to ever draw a distinct line in the sand between the two? A book with a name like The Water Castle (mistakenly read by my library’s security guard as “White Castle”) could fall on either side of the equation, though castles generally are the stuff of fantastical fare. In this particular case, however, what we have here is a smart little bit of middle grade chapter book science fiction, complete with arson, obsession, genetic mutation, and a house any kid would kill to live in. Smarter than your average bear, this is one book that rewards its curious readers. It’s a pleasure through and through.

Welcome to Crystal Springs, Maine where all the women are strong, all the men are good-looking, and all the children are above average. That last part seems to be true, anyway. When Ephraim Appledore, his two siblings, his mom, and his father (suffering from the after effects of a stroke) move to town he’s shocked to find that not only does everyone seem to know more about his family history than he does, they’re all geniuses to boot. The Appledores have taken over the old Water Castle built by their ancestors and harboring untold secrets. When he’s not exploring it with his siblings Ephraim finds two unlikely friends in fellow outcast Mallory Green and would-be family feuder Will Wylie. Together they discover that the regional obsession with the fountain of youth may have some basis in reality. A reality that the three of them are having trouble facing, for individual reasons.

When one encounters an old dusty castle hiding trapdoors and secret passageways around every corner, that usually means your feet are planted firm in fantasy soil. All the elements are in place with Ephraim akin to Edwin in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe and a dusty old wardrobe even making a cheeky cameo at one point. What surprised me particularly was the book’s grounding instead in science fiction. That said, how far away from fantasy is science fiction in children’s literature? In both cases the fantastical is toyed with. In this particular case, eternal life finds its basis in discussions of mutant genes, electricity, radiation, and any number of other science-based theories. Interestingly, it’s actually hard to come up with many children’s books that even dwell on the fountain of youth. There’s Tuck Everlasting of course, but that’s about as far as it goes. One gets the impression that Babbitt did such a good job with the idea that no one’s had the guts to take it any farther since. Kudos to Blakemore then for rising to the challenge.

I’m very partial to children’s books that are magical if you want them to be and realistic if that’s what you’d prefer. This year’s Doll Bones by Holly Black, for example, could be an uber-creepy horror story or it could just be a tale of letting your imagination run away with you. Similarly The Water Castle could be about the true ramifications of eternal life, or it could be explained with logic and reason every step of the way. I was also rather interested in how Ms. Blakemore tackled that age-old question of how to allow your child heroes the freedom to come and go as they please without a droplet of parental supervision. In this case her solution (father with a stroke and a mother as his sole caretaker) not only worked effectively but also tied in swimmingly into our hero’s personal motivations.

In the midst of a review like this I sometimes have a bad habit of failing to praise the writing of a book. That would be a particular pity in this case since Ms. Blakemore sucked me in fairly early on. When Ephraim and his family drive into town for the first time we get some beautiful descriptions of the small town itself. “They rolled past the Wylie Five and Dime, which was advertising a sale on gourds, Ouija boards, and pumpkin-pie filling.” She also has a fine ear for antiquated formal speech, though the physical appearances of various characters are not of particular importance to her (example: we don’t learn that Ephraim’s little sister Brynn is blond until page 183).

An interesting aspect of the writing is its tackling of race, racism, and historical figures done wrong by their times. I was happy from the get-go that Ms. Blakemore chose to make her cast a multi-cultural one. Mallory is African-American, one of the few in town, and is constantly being offered subjects like Matthew Henson for class reports because . . . y’know. Henson himself plays nicely into a little subplot in the book. Deftly Ms. Blakemore draws some similarities between his work with Robert Peary and Tesla’s attitude towards Edison. Nothing too direct. Just enough information where kids can connect the dots themselves. For all this, I was a bit disappointed that when we read some flashbacks into the past there doesn’t seem to be ANY racism in sight. We follow the day-to-day activities of an African-American girl and the various rich white people she encounters and yet only ONE mention is made of their different races in a vague reference to the fact that our heroine’s family has never been slaves. This seemed well-intentioned but hugely misleading. Strange to discuss Henson and Peary in one breath and then ignore everyday realities on the other.

If the book has any other problems there is the fact that the author leaves the essential question about the mysterious water everyone searches for in this story just that. Mysterious. There are also some pretty heady clues dropped about Mallory’s own parents that remain unanswered by the tale’s end. Personally, I am of the opinion that Ms. Blakemore did this on purpose for the more intelligent of her child readers. I can already envision children’s bookgroups discussing this title at length, getting into arguments about what exactly it means that Mallory’s mom had that key around her neck.

In the end, The Water Castle is less about the search for eternal life and youth than it is about letting go of childhood and stories. Age can come when you put those things away. As Ephraim ponders late in the game, “No one back in Cambridge would believe that he’d been crawling around in dark tunnels, or climbing up steps with no destination. Maybe, he decided, growing up meant letting go of the stories, letting go in general, letting yourself fall just to see if you could catch yourself. And he had.” Whether or not Ms. Blakemore chooses to continue this book with the further adventures of Ephraim, Mallory and Will, she’s come up with a heckuva smart little creation. Equally pleasing to science fiction and fantasy fans alike, there’s enough meat in this puppy for any smart child reader or bored kid bookgroup. I hope whole droves of them find it on their own. And I hope they enjoy it thoroughly. A book that deserves love.

On shelves now.

Source: Final copy sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

Tuck Everlasting by Natalie Babbitt

The House of Dies Drear by Virginia Hamilton

When You Reach Me by Rebecca Stead

Notes on the Cover: Is that or is that not a fantasy cover? The ivy strangled stone gargoyles and castle in the background all hint at it. I wasn’t overly in love with this jacket at first, but in time I’ve discovered that kids are actually quite drawn to it. Whether or not they find it misleading, time will tell. Not having read the bookflap description of this title, I spent an embarrassingly long amount of time trying to turn the kids on the cover into Ephraim and his siblings. It was quite a while before I realized my mistake.

Professional Reviews:

Other Blog Reviews: Cracking the Cover

Interviews: Portland Press Herald

Misc: Check out the Teacher’s Guide for this book.

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 1/30/2013

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reviews,

middle grade fiction,

unreliable narrators,

funny books,

Best Books,

Candlewick,

Stephan Pastis,

notebook novels,

middle grade funny books,

Best Books of 2013,

Reviews 2013,

2013 funny books,

2013 reviews,

2013 middle grade fiction,

Add a tag

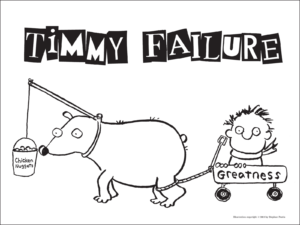

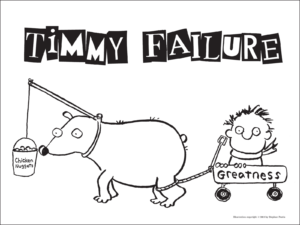

Timmy Failure: Mistakes Were Made

Timmy Failure: Mistakes Were Made

By Stephan Pastis

Candlewick Press

$14.99

ISBN: 978-0-7636-6050-5

Ages 9-12

On shelves February 26th

Call it the attack of the syndicated cartoonists. For whatever reason, in the year 2013 we are seeing droves of escapees from the comic strip pages leaping from the burning remains of the newspaper industry into the slightly less volatile world of books for kids. How different could it be, right? As a result you’ve The Odd Squad by Michael Fry (Over the Hedge) and Zits Chillax by Jerry Scott (Zits). Even editorial cartoonists are getting in on the act with Pulitzer prize winner Matt Davies and his picture book Ben Rides On. In the old days it was usually animators, greeting card designers, and Magic the Gathering illustrators who joined the children’s book fray. But now with graphic novels getting better than ever and libraries willing to buy the bloody things, the world has been made safe for cartoonists too. Into this state of affairs comes Timmy Failure: Mistakes Were Made. It is, without a doubt, the best of the cartoonist fare (author Stephan Pastis is the man behind the strip Pearls Before Swine), completely and utterly understanding its genre, its pacing, and the importance of leveling humor with down-to-earth human problems. Funnier than it deserves to be, here’s the book to hand the kind who has been told to read something with an unreliable narrator. Trust me, you’ll be the kid’s best friend if you give them this.

Meet Detective Failure. No, not really. Instead, meet Timmy Failure, just a normal kid with dreams so big they make Walter Mitty’s fantasies look like idle fancies. Living with just his single mom and his sidekick Total (a 1,500 pound polar bear but that’s neither here nor there), Timmy spends his days solving crimes for the other kids in his class. He may not be very good at it but it’s a living. Timmy’s sure his talents will launch him into a future of fame an fortune. That is, if he can defeat his nemesis Corrina Corrina, get his mom to stop grounding him, deal with the loser she’s dating, and figure out how to keep Total out of a zoo. It’s a big job. Fortunately, Timmy has a more than hefty ego to handle it.

I am a grown woman with a child of my own. I am an adult. I pay bills and watch Masterpiece Theater. In other words, my grown-up cred is in place. That said, I can’t tell you how many debates I’ve already had with folks over whether or not Timmy’s darn polar bear is real or not. My husband claims that the bear is a manifestation of Timmy’s break with reality in the same way that Hobbes seemed to walk around in the comic strip Calvin and Hobbes. I like to point out that Hobbes had an actual physical form as a stuffed tiger and where precisely is the stuffed polar bear in all this? Maybe I have a hard time acknowledging the fact that Total isn’t real because if that’s true then Timmy’s life is even sadder than I initially thought.

Because, you see, that’s the real joy of Timmy Failure; the misery. On the one hand we are meant to yell and scream at our oblivious hero and to mock him for his inability to face reality. On the other hand, when you see how sad his life is, you cannot help but feel for him. That poignancy almost makes it funny again. His mom, for example, is single and holding down a low-income job as best she can. It’s not her fault her kiddo is as detached from the world around him as he is. And Timmy, truth be told, pretends to be a detective mostly because he wants to give his mom a better life. His bravado is hiding some pretty desperate hopes and dreams. You get glimpses past that bravado from time to time, and those are the moments that lift the book up and out of the world of pseudo-Diary of a Wimpy Kid notebook novel knock-offs that clog library and bookseller shelves. For example, there’s one moment when Timmy’s mom cuddles him then blows into his ear because he finds it funny. He objects in his usual staunch way then . . . “Do it again”. The book also dares to take potshots at folks who might actually deserve it. Timmy’s teacher has checked out of teaching long since. He’s the kind of guy who hasn’t cared about what he’s doing in years. Should’ve retired a decade or more ago. When you see that, can you help but love the hell Timmy drags him through?

Because, you see, that’s the real joy of Timmy Failure; the misery. On the one hand we are meant to yell and scream at our oblivious hero and to mock him for his inability to face reality. On the other hand, when you see how sad his life is, you cannot help but feel for him. That poignancy almost makes it funny again. His mom, for example, is single and holding down a low-income job as best she can. It’s not her fault her kiddo is as detached from the world around him as he is. And Timmy, truth be told, pretends to be a detective mostly because he wants to give his mom a better life. His bravado is hiding some pretty desperate hopes and dreams. You get glimpses past that bravado from time to time, and those are the moments that lift the book up and out of the world of pseudo-Diary of a Wimpy Kid notebook novel knock-offs that clog library and bookseller shelves. For example, there’s one moment when Timmy’s mom cuddles him then blows into his ear because he finds it funny. He objects in his usual staunch way then . . . “Do it again”. The book also dares to take potshots at folks who might actually deserve it. Timmy’s teacher has checked out of teaching long since. He’s the kind of guy who hasn’t cared about what he’s doing in years. Should’ve retired a decade or more ago. When you see that, can you help but love the hell Timmy drags him through?

I wonder to myself how far kids will go to believe Timmy. The book sets you up pretty early to understand how unreliable he is but there may be times when gullible readers believe what he says. They might actually think that Flo the librarian (a guy who looks like he’d be more comfortable pounding rocks on a chain gang than running a library) really does read books about crushing things with your fists. All the more reason Timmy is confused when he catches the man reading Emily Dickinson. “And if she can crush things with her fist, her photo is somewhat misleading.”

In the course of any of this have I actually mentioned that the book is guffaw-worthy? Laugh-out-loud funny? Look, any book where the main character reasons that since the name “Chang” is the most common in the world he should automatically fill it in on all his test papers because the odds would be with him has my interest. Add in the fact that you’ve titles of chapters with names like, “You may find yourself behind the wheel of a large automobile” (well played, Pastis) and visual moments where Timmy is holding a box of rice krispie treats above his head ala Say Anything. Clearly this is adult humor, but when he hits it on the kid level (which is all the time) the readers will be rolling.

The art is, of course, sublime. Look at Timmy himself if you don’t believe me. On the cover of the book he looks pretty okay but turn the pages and there’s definitely something a little bit off about him. Did you figure out what it was? Look at his eyes. With the greatest of care Pastis has places one pupil dead in the center of Timmy’s eye and the in the other eye the pupil is juuuuuuuuust barely off-center. It’s not the kind of thing you’d necessarily notice consciously. You’d just be left with the clear sense that there’s something off about this kid. Then there’s the fact that all the characters are often staring right at you. Right in the eye. It reminded me of Jon Klassen’s I Want My Hat Back. Same school play feel. Same wary characters.

The art is, of course, sublime. Look at Timmy himself if you don’t believe me. On the cover of the book he looks pretty okay but turn the pages and there’s definitely something a little bit off about him. Did you figure out what it was? Look at his eyes. With the greatest of care Pastis has places one pupil dead in the center of Timmy’s eye and the in the other eye the pupil is juuuuuuuuust barely off-center. It’s not the kind of thing you’d necessarily notice consciously. You’d just be left with the clear sense that there’s something off about this kid. Then there’s the fact that all the characters are often staring right at you. Right in the eye. It reminded me of Jon Klassen’s I Want My Hat Back. Same school play feel. Same wary characters.

It should be of little surprise that the guy behind the Pearls Before Swine comic strip should also produce some fan-tastic animals. My favorite is Senor Burrito, a cat who dunks her paw into Timmy’s tea whenever he turns his head. The image of her sitting there, one paw well past her elbow in a teacup, is so good I’d rip it out of the book and frame it if I could justify the act of defacement.

When Seinfeld first came out the unofficial slogan was “No hugging. No learning.” If there’s a motto to be ascribed to Timmy Failure I may have to be “No learning. No growing. Hugs allowed.” Basically this is Calvin and Hobbes if Calvin’s fantasies were based entirely on how great he is. A step above the usual notebook novel fare, it dares to have a little bit of heart embedded amidst the madcap craziness. Timmy won’t be everybody’s cup of tea, but for a certain segment of the population his adventures will prove to be precisely the kind of balm they need. Top notch stuff. A cut above the cartoons.

On shelves February 26th.

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

First Line: “It’s harder to drive a polar bear into somebody’s living room than you’d think.”

Like This? Then Try:

Professional Reviews: Kirkus

Other Reviews: Shelf Awareness

Misc:

- I’ve been enjoying the blog for the book. Particularly the posts by Flo the Librarian. Such a sweet feller. The next guybrarian who dresses up as Flo for Halloween has my undying love.

- Read a sample chapter here.

Videos:

Here’s a sneaky peek.

Here’s the full-length trailer:

And here’s the author himself on the polar bear. Actually, this clears quite a lot of stuff up.

The Other Side of Free

The Other Side of Free

I agree about the cover. Your review doesn’t make this sound like a dark depressing book but the cover looks like your standard Boy-running-from-slavery-sure-to-be-caught cover.

I know, right? What is it with historical novels starring African-Americans and dark depressing book jackets? Don’t we WANT kids to pick the books up once in a while on their own?

Totally agree on the cover. And I really liked How To Become a Famous Novelist – that book cracked me up.