new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Charles Dickens, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 26 - 50 of 89

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Charles Dickens in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Alice,

on 6/23/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Literature,

charles dickens,

Oxford World's Classics,

great expectations,

Bryant Park,

Humanities,

Maura Kelly,

*Featured,

Bryant Park summer reading,

Much Ado About Loving,

Word for Word Book Club,

rodger,

Add a tag

Each summer, Oxford University Press USA and Bryant Park in New York City partner for their summer reading series Word for Word Book Club. The Bryant Park Reading Room offers free copies of book club selections while supply lasts, compliments of Oxford University Press, and guest speakers lead the group in discussion. On Tuesday 24 June 2014, Maura Kelly, author of Much Ado About Loving, leads a discussion on Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations.

By Maura Kelly

Great Expectations is arguably Charles Dickens’s finest novel – it has a more cogent, concise plot and a more authentic narrator than the other contender for that title, the sprawling masterpiece Bleak House. It may also enjoy another special distinction – Best Title for Any Novel Ever. Certainly, it might have served as the name for any of Dickens’s other novels, as the critic G. K. Chesterson has noted before me. “All of his books are full of an airy and yet ardent expectation of everything … of the next event, of the next ecstasy; of the next fulfillment of any eager human fancy,” wrote Chesterson. What’s more, it might have been used for a number of the best novels written by any author – American novels in particular. Think of The Great Gatsby, Absalom, Absalom, Invisible Man, or Revolutionary Road. The same goes for Saul Bellow’s short tour de force, Seize the Day, or that of Henry James, The Beast in the Jungle. But think too of Balzac’s novel Lost Illusions, nearly a synonym for Dickens’s phrase, or another French book, Madame Bovary. Think of all the works of Jane Austen, with the various expectations that so many characters in every one of her books have about who should marry whom. And on and on.

But think too of most life stories, most personal narratives: Might they not also be called Great Expectations? For what are our lives but our attempts to realize our dreams about what we might become, and to either castigate or console ourselves if we don’t?

Miss Havisham, Pip, and Estella, in art from the Imperial Edition of Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations. Art by H. M. Brock. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

In Pip, the hero of

Great Expectations, we have a character who is something of a combination of a Gatsby and an Austen heroine. He is fixated on attaining romantic union that will, he believes, quiet his persistent feelings of self-loathing and inadequacy; he is also all too painfully aware that he is not of the right class to attract that person. As a youth, Pip feverishly hopes that he will miraculously come into money so that he might win the heart of his Daisy – the beautiful, haughty, wealthy Estella. If Pip were a character living in America, he might have done more than dream about getting rich quick – he might have gone the Gatsby route, or the route of any number of Horatio Alger protagonists. However, living in England as he does – where for centuries, people were either born into the aristocracy or they weren’t – Pip doesn’t do much more than fantasize. Nonetheless, thanks to the magic of Dickens’s narrative, through a turn of fate that seems quite plausible in the world of the novel, into money Pip does mysteriously come. And yet, despite his newfound wealth and status, he can’t “get the girl” – the girl who is not simply the person with the power to cure Pip of his terrible sickness of the soul, but the very same girl who inflicted him with that psychological malady when she disdained Pip as a child, calling him “coarse” and “common” and generally making it clear that she thought him beneath her.

One more story that might have been called Great Expectations is that of Elliot Rodger, the young man with a BMW, a closet full not of silk shirts but Armani sweaters, and a trove of guns who killed six college students during a shooting spree in California a couple of weeks ago. Judging from the manifesto he left behind, he did not get the girls; he was scorned by beautiful women; his life had fallen woefully short of his expectations. Who can say just how that troubled young man developed his expectations, but he was what you might call a spawn by Hollywood; his parents met on a movie set, after all. And if there is any city in the world that might be called the city of Great Expectations, Los Angeles has to be it, where the world’s most visible examples of glamorous, glittering success serve as foils to some of the most desperate characters around – the red-eyed and unhinged hopefuls who have been hanging around for years or decades, hoping for the big break that never comes.

Rodger’s father seems to have had experiences on both ends of the success spectrum: Though he directed some extra shots for “The Hunger Games,” he also spent $200,000 of his own money on a documentary that sold only a “handful of tickets,” according to The New York Times. Rodger seems to have resented his father: “If only my failure of a father had made better decisions with his directing career instead wasting his money on that stupid documentary,” he wrote. And Pip, too, resents his multiple father figures – at first, at least. But unlike Rodger, Pip works through his resentment, and in doing so, finds his redemption.

When Pip’s biological father dies, he is adopted by his sister’s humble husband, the kindly if simple blacksmith Joe Gargery. Though Joe serves as the main source of comfort, happiness, and stability in Pip’s young life, when Estella infects Pip with shame, he becomes ashamed of Joe, too; thinking him too much a country bumpkin, Pip distances himself from Joe. He reacts in a similar way to the other father figure of the novel, Abel Magwitch. A good-hearted criminal, Magwitch bestows an honest fortune on the adult Pip out of gratitude for some help that a frightened young Pip had given him during an escape attempt he made years ago. Pip more or less recoils in horror when Magwitch explains that he’s the one who’s been funding Pip’s life as a gentleman. But Pip eventually pushes his through his feelings of mortification and revulsion in order to do the right thing. He repays Magwitch’s loving kindness with some loving kindness of his own, by helping the old convict attempt to evade capture after he returns to England despite threat of death, because he so much wants to see Pip.

Pip’s overcoming his lesser self in this way “is not a simple recovery from snobbery, but courage of a rare and fine kind,” according to critic A. E. Dyson. Scholar Sylvere Monod writes that the only reason Pip is able to propel himself to such courage is because he has been on a “groping quest … for the truth, not only about the world and the society among which he lives, but also, and more importantly, about himself.” That quest is what allows him to come to a greater acceptance of both himself, at the end of the novel, and his two adoptive fathers – men who, for all their lack of societal cache, have always done for Pip something that neither Estella nor Pip himself were able to: love Pip more or less unconditionally.

“Poor, miserable, fellow creature” : it is a phrase often repeated by humble Joe Gargery, and it helps to point to the lessons about empathy and acceptance that Pip must learn. While it likely would not have been possible for someone like Elliot Rodger to have derived much from Great Expectations, plenty of other readers – like this one – can continue to rely on it as a source of wisdom and comfort, as an inspiration for humility and a font of hilarity, as we grapple with our own feelings of doubt and worthlessness, with the disparity between our own great expectations and the disappointing realities of our lives. “This is the Dickens novel the mature and exigent are now likely to re-read most often and to find more and more in each time,” wrote British literary critic Q. D. Leavis in 1970, “perhaps because it seems to have more relevance outside its own age than any other of Dickens’s creative work.” That is as true now as it was when Great Expectations first appeared in serial form in 1860.

Maura Kelly writes personal essays, profiles and op-eds. Her new book, Much Ado About Loving: What Our Favorite Novels Can Teach You About Date Expectations, Not-So-Great Gatsbys and Love in the Time of Internet Personals, is a hybrid of memoir, lit crit and advice column. She graduated from Dartmouth College and received her MFA in fiction writing from George Mason University. She started her career with jobs at The Washington Post and Slate. She has been a staff writer for Glamour, a daily dating blogger for Marie Claire and a relationships columnist for amNew York. Her writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Daily Beast, The Daily, The New York Observer, Salon, The Guardian, The Boston Globe Magazine, Rolling Stone, More and other publications and anthologies.

Maura Kelly writes personal essays, profiles and op-eds. Her new book, Much Ado About Loving: What Our Favorite Novels Can Teach You About Date Expectations, Not-So-Great Gatsbys and Love in the Time of Internet Personals, is a hybrid of memoir, lit crit and advice column. She graduated from Dartmouth College and received her MFA in fiction writing from George Mason University. She started her career with jobs at The Washington Post and Slate. She has been a staff writer for Glamour, a daily dating blogger for Marie Claire and a relationships columnist for amNew York. Her writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Daily Beast, The Daily, The New York Observer, Salon, The Guardian, The Boston Globe Magazine, Rolling Stone, More and other publications and anthologies.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter and Facebook. Read previous interviews with Word for Word Book Club guest speakers.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post On Great Expectations appeared first on OUPblog.

By:

Becky Laney,

on 6/9/2014

Blog:

Becky's Book Reviews

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Nonfiction,

adult nonfiction,

Charles Dickens,

favorite authors,

1853,

1854,

book I bought,

1852,

1851,

books reviewed in 2014,

Add a tag

A Child's History of England. Charles Dickens. 1851-1853. 390 pages. [Source: Book I Bought]

What a treat to discover Charles Dickens' A Child's History of England. I enjoyed Dickens style. I liked the action and characterization. It was also rich in description. Here's the first sentence,

"In the old days, a long, long while ago, before Our Saviour was born on earth and lay asleep in a manger, these Islands were in the same place, and the stormy sea roared round them, just as it roars now. But the sea was not alive, then, with great ships and brave sailors, sailing to and from all parts of the world. It was very lonely. The Islands lay solitary, in the great expanse of water. The foaming waves dashed against their cliffs, and the bleak winds blew over their forests; but the winds and waves brought no adventurers to land upon the Islands, and the savage Islanders knew nothing of the rest of the world, and the rest of the world knew nothing of them."

Not that every sentence is that scripted or forced. The book itself is very readable. The chapters are rarely--if ever--boring. That being said, some chapters are more exciting than others.

I recently read Jane Austen's History of England. Dickens is definitely partial and prejudiced in his historical approach as well, even, if his book tries (with varying success) to carry more authority and substance. While I think Austen approached her work in fun with a good amount of playfulness, Dickens takes his subject much more seriously. While one can entertain doubts that Austen truly means every word she wrote in A History of England, Dickens opinions, which are even harsher in some ways, sound genuine enough. For better or worse. I don't have a problem with historians having opinions, and being passionate about the subject. But it's always nice to know that they know it's all so very subjective. Dickens and I would definitely disagree in places!!! Especially when he includes women in his history. And especially about Richard III!

Strengths:

- Begins around the time of the Romans, ends around 1688 Revolution

- Covers centuries of stories and legends and facts

- Mainly focuses on royalty

- Seeks to explain big subjects simply

- Written with emphasis on characters and personalities

- Shows the subjectivity of history

Quotes:

Hengist and Horsa drove out the Picts and Scots; and Vortigern, being grateful to them for that service, made no opposition to their settling themselves in that part of England which is called the Isle of Thanet, or to their inviting over more of their countrymen to join them. But Hengist had a beautiful daughter named Rowena; and when, at a feast, she filled a golden goblet to the brim with wine, and gave it to Vortigern, saying in a sweet voice, ‘Dear King, thy health!’ the King fell in love with her. My opinion is, that the cunning Hengist meant him to do so, in order that the Saxons might have greater influence with him; and that the fair Rowena came to that feast, golden goblet and all, on purpose.

But the Duke showed so little inclination to do so now, that he proposed to Canute to marry his sister, the widow of The Unready; who, being but a showy flower, and caring for nothing so much as becoming a queen again, left her children and was wedded to him.

The King’s brother, Robert of Normandy, seeming quite content to be only Duke of that country; and the King’s other brother, Fine-Scholar, being quiet enough with his five thousand pounds in a chest; the King flattered himself, we may suppose, with the hope of an easy reign. But easy reigns were difficult to have in those days. [The King was William II]

Although King Stephen was, for the time in which he lived, a humane and moderate man, with many excellent qualities; and although nothing worse is known of him than his usurpation of the Crown, which he probably excused to himself by the consideration that King Henry the First was a usurper too — which was no excuse at all; the people of England suffered more in these dread nineteen years, than at any former period even of their suffering history. In the division of the nobility between the two rival claimants of the Crown, and in the growth of what is called the Feudal System (which made the peasants the born vassals and mere slaves of the Barons), every Noble had his strong Castle, where he reigned the cruel king of all the neighbouring people. Accordingly, he perpetrated whatever cruelties he chose. And never were worse cruelties committed upon earth than in wretched England in those nineteen years. The writers who were living then describe them fearfully. They say that the castles were filled with devils rather than with men; that the peasants, men and women, were put into dungeons for their gold and silver, were tortured with fire and smoke, were hung up by the thumbs, were hung up by the heels with great weights to their heads, were torn with jagged irons, killed with hunger, broken to death in narrow chests filled with sharp-pointed stones, murdered in countless fiendish ways. In England there was no corn, no meat, no cheese, no butter, there were no tilled lands, no harvests. Ashes of burnt towns, and dreary wastes, were all that the traveller, fearful of the robbers who prowled abroad at all hours, would see in a long day’s journey; and from sunrise until night, he would not come upon a home. The clergy sometimes suffered, and heavily too, from pillage, but many of them had castles of their own, and fought in helmet and armour like the barons, and drew lots with other fighting men for their share of booty. The Pope (or Bishop of Rome), on King Stephen’s resisting his ambition, laid England under an Interdict at one period of this reign; which means that he allowed no service to be performed in the churches, no couples to be married, no bells to be rung, no dead bodies to be buried. Any man having the power to refuse these things, no matter whether he were called a Pope or a Poulterer, would, of course, have the power of afflicting numbers of innocent people. That nothing might be wanting to the miseries of King Stephen’s time, the Pope threw in this contribution to the public store — not very like the widow’s contribution, as I think, when Our Saviour sat in Jerusalem over-against the Treasury, ‘and she threw in two mites, which make a farthing.’

He had four sons. Henry, now aged eighteen — his secret crowning of whom had given such offence to Thomas à Becket. Richard, aged sixteen; Geoffrey, fifteen; and John, his favourite, a young boy whom the courtiers named Lackland, because he had no inheritance, but to whom the King meant to give the Lordship of Ireland. All these misguided boys, in their turn, were unnatural sons to him, and unnatural brothers to each other. Prince Henry, stimulated by the French King, and by his bad mother, Queen Eleanor, began the undutiful history, First, he demanded that his young wife, Margaret, the French King’s daughter, should be crowned as well as he. His father, the King, consented, and it was done. It was no sooner done, than he demanded to have a part of his father’s dominions, during his father’s life. This being refused, he made off from his father in the night, with his bad heart full of bitterness, and took refuge at the French King’s Court. Within a day or two, his brothers Richard and Geoffrey followed. Their mother tried to join them — escaping in man’s clothes — but she was seized by King Henry’s men, and immured in prison, where she lay, deservedly, for sixteen years. [Henry II and his children]

Nothing can make war otherwise than horrible.

Ah! happy had it been for the Maid of Orleans, if she had resumed her rustic dress that day, and had gone home to the little chapel and the wild hills, and had forgotten all these things, and had been a good man’s wife, and had heard no stranger voices than the voices of little children!

Sir Robert Brackenbury was at that time Governor of the Tower. To him, by the hands of a messenger named John Green, did King Richard send a letter, ordering him by some means to put the two young princes to death. But Sir Robert — I hope because he had children of his own, and loved them — sent John Green back again, riding and spurring along the dusty roads, with the answer that he could not do so horrible a piece of work. The King, having frowningly considered a little, called to him Sir James Tyrrel, his master of the horse, and to him gave authority to take command of the Tower, whenever he would, for twenty-four hours, and to keep all the keys of the Tower during that space of time. Tyrrel, well knowing what was wanted, looked about him for two hardened ruffians, and chose John Dighton, one of his own grooms, and Miles Forest, who was a murderer by trade. Having secured these two assistants, he went, upon a day in August, to the Tower, showed his authority from the King, took the command for four-and-twenty hours, and obtained possession of the keys. And when the black night came he went creeping, creeping, like a guilty villain as he was, up the dark, stone winding stairs, and along the dark stone passages, until he came to the door of the room where the two young princes, having said their prayers, lay fast asleep, clasped in each other’s arms. And while he watched and listened at the door, he sent in those evil demons, John Dighton and Miles Forest, who smothered the two princes with the bed and pillows, and carried their bodies down the stairs, and buried them under a great heap of stones at the staircase foot. And when the day came, he gave up the command of the Tower, and restored the keys, and hurried away without once looking behind him; and Sir Robert Brackenbury went with fear and sadness to the princes’ room, and found the princes gone for ever.

We now come to King Henry the Eighth, whom it has been too much the fashion to call ‘Bluff King Hal,’ and ‘Burly King Harry,’ and other fine names; but whom I shall take the liberty to call, plainly, one of the most detestable villains that ever drew breath. You will be able to judge, long before we come to the end of his life, whether he deserves the character.

Her bad marriage with a worse man came to its natural end. Its natural end was not, as we shall too soon see, a natural death for her.

Henry the Eighth has been favoured by some Protestant writers, because the Reformation was achieved in his time. But the mighty merit of it lies with other men and not with him; and it can be rendered none the worse by this monster’s crimes, and none the better by any defence of them. The plain truth is, that he was a most intolerable ruffian, a disgrace to human nature, and a blot of blood and grease upon the History of England.

Mary was now crowned Queen. She was thirty-seven years of age, short and thin, wrinkled in the face, and very unhealthy. But she had a great liking for show and for bright colours, and all the ladies of her Court were magnificently dressed. She had a great liking too for old customs, without much sense in them; and she was oiled in the oldest way, and blessed in the oldest way, and done all manner of things to in the oldest way, at her coronation. I hope they did her good. She soon began to show her desire to put down the Reformed religion, and put up the unreformed one: though it was dangerous work as yet, the people being something wiser than they used to be. They even cast a shower of stones — and among them a dagger — at one of the royal chaplains who attacked the Reformed religion in a public sermon. But the Queen and her priests went steadily on.

It would seem that Philip, the Prince of Spain, was a main cause of this change in Elizabeth’s fortunes. He was not an amiable man, being, on the contrary, proud, overbearing, and gloomy; but he and the Spanish lords who came over with him, assuredly did discountenance the idea of doing any violence to the Princess. It may have been mere prudence, but we will hope it was manhood and honour. The Queen had been expecting her husband with great impatience, and at length he came, to her great joy, though he never cared much for her.

She was clever, but cunning and deceitful, and inherited much of her father’s violent temper. I mention this now, because she has been so over-praised by one party, and so over-abused by another, that it is hardly possible to understand the greater part of her reign without first understanding what kind of woman she really was... The Queen always declared in good set speeches, that she would never be married at all, but would live and die a Maiden Queen. It was a very pleasant and meritorious declaration, I suppose; but it has been puffed and trumpeted so much, that I am rather tired of it myself... It is very difficult to make out, at this distance of time, and between opposite accounts, whether Elizabeth really was a humane woman, or desired to appear so, or was fearful of shedding the blood of people of great name who were popular in the country. [About Queen Elizabeth]

‘Our cousin of Scotland’ was ugly, awkward, and shuffling both in mind and person. His tongue was much too large for his mouth, his legs were much too weak for his body, and his dull goggle-eyes stared and rolled like an idiot’s. He was cunning, covetous, wasteful, idle, drunken, greedy, dirty, cowardly, a great swearer, and the most conceited man on earth... While these events were in progress, and while his Sowship was making such an exhibition of himself, from day to day and from year to year, as is not often seen in any sty... [About King James I]

Baby Charles became King Charles the First, in the twenty-fifth year of his age. Unlike his father, he was usually amiable in his private character, and grave and dignified in his bearing; but, like his father, he had monstrously exaggerated notions of the rights of a king, and was evasive, and not to be trusted. If his word could have been relied upon, his history might have had a different end... With all my sorrow for him, I cannot agree with him that he died ‘the martyr of the people;’ for the people had been martyrs to him, and to his ideas of a King’s rights, long before.

There never were such profligate times in England as under Charles the Second. Whenever you see his portrait, with his swarthy, ill-looking face and great nose, you may fancy him in his Court at Whitehall, surrounded by some of the very worst vagabonds in the kingdom (though they were lords and ladies), drinking, gambling, indulging in vicious conversation, and committing every kind of profligate excess. It has been a fashion to call Charles the Second ‘The Merry Monarch.’ Let me try to give you a general idea of some of the merry things that were done, in the merry days when this merry gentleman sat upon his merry throne, in merry England. The first merry proceeding was — of course — to declare that he was one of the greatest, the wisest, and the noblest kings that ever shone, like the blessed sun itself, on this benighted earth. The next merry and pleasant piece of business was, for the Parliament, in the humblest manner, to give him one million two hundred thousand pounds a year, and to settle upon him for life that old disputed tonnage and poundage which had been so bravely fought for.

King James the Second was a man so very disagreeable, that even the best of historians has favoured his brother Charles, as becoming, by comparison, quite a pleasant character.

As you can see, Dickens is very, very, very opinionated! A Child's History of England is an interesting and entertaining read for the history lover.

© 2014 Becky Laney of

Becky's Book Reviews

Tristram Shandy still being in my not long ago reading memory I could not help but compare the opening of that book to David Copperfield.

A memory refresher in case it has been a while since you read either book or in case you have never read them at all.

Tristram Shandy begins:

I wish either my father or my mother, or indeed both of them, as they were in duty both equally bound to it, had minded what they were about when they begot me; had they duly consider’d how much depended upon what they were then doing;—that not only the production of a rational Being was concerned in it, but that possibly the happy formation and temperature of his body, perhaps his genius and the very cast of his mind;—and, for aught they knew to the contrary, even the fortunes of his whole house might take their turn from the humours and dispositions which were then uppermost;—Had they duly weighed and considered all this, and proceeded accordingly,—I am verily persuaded I should have made a quite different figure in the world, from that in which the reader is likely to see me.

And David Copperfield:

I was born (as I have been informed and believe) on a Friday, at twelve o’clock at night.

Both books are coming of age stories written from the perspective of a later date and both books begin at the beginning only it takes Tristram nearly half to book to actually get born where David does it in the first sentence. Both books are more about character than plot and filled with digressions. But the whole point of Tristram is the digression and Copperfield always comes back to a main progression toward a firm conclusion. Tristram ends with a joke and loose ends flying everywhere, while Copperfield ends with everything wrapped up and tied with a neat little bow. I’ve no further comparisons to make or brilliant observations, I only wanted to remark how fascinating literature is that you can have the same basic story told in two completely different ways.

What I found really interesting about David Copperfield is how all the characters come in pairs except for David, he is left alone until late in the book. There are the brother and sister Murdstones, Dr. Strong and Mrs. Strong, Mr. Wickfield and his daughter Agnes, Mr. and Mrs. Micawber, Uriah Heep and his mother, David’s aunt and Mr. Dick, Steerforth and his butler Littimer. Everybody has somebody except David who goes from pairing to pairing, learning from each while being cared for or hated.

I would have thought that in all these relational pairings David would have learned something about pairing up himself, but alas, he makes the same mistake his father made and chooses a “child-wife.” When he gets a second chance he makes the correct choice but he had to learn the hard way.

In spite of its length and lack of real drama, David Copperfield moves along pretty well without bogging down at all. It does bog down though. The last 15% of the book dragged as David went on his European tour to get over his grief at losing Dora and as Dickens felt compelled to tie up all the ends. The wrapping up went on and on and on as characters died, got put in jail, or shipped out to Australia. Australia solved a lot of problems for Dickens in this book. Need to get rid of a thief? Send him to Australia! Need a fresh start? Go to Australia! It actually got to be kind of funny. It’s a good thing Dickens had so many characters to dispose of, which was probably the problem in the first place. Nonetheless, good book. And if you like Dickens you are sure to enjoy David Copperfield.

Filed under:

Books,

Charles Dickens,

Reviews

I’m a little over 80% of the way through David Copperfield. I give you a percentage because I am reading it on my Kindle and I have no idea what this looks like in terms of the print book. I am enjoying the book very much but I have come to a place where I feel guilty.

You see earlier in the book David met and fell in love with Dora. Dora is an affectionate airhead and so completely the wrong woman for David. But youth and love and youth in love don’t always make the best choices. And so David marries her in spite me repeatedly telling him not to. It is so frustrating when characters do not obey one’s wishes! And of course the marriage is a disaster, though David doesn’t realize it at first while in the clutches of newlywed bliss. But as time goes on and Dora refuses to act anything other than a child, he regrets his choice. He loves her still, but he wishes he had someone with sense with whom he could actually talk about things.

While David continues to love Dora in spite of all, she is nails on a chalkboard to me and I just want to slap her. Hard. I, of course, know exactly who David should marry. And so I have been reading and hoping that maybe something will happen to Dora. I thought she could die in childbirth and that would be just fine.

Then we are told she has a baby, but the baby was sickly and dies very soon after birth. Dora, however, never quite recovers and she begins a slow decline. I almost cheered. Dora’s going to die and David can marry the right person, hooray! And then I felt really, really guilty. As Dora goes downhill she makes me feel worse and worse for wishing her dead. For in her decline she remains cheerful, sunny, and affectionate which shows she has some strength of character in there after all. In my wish for her demise I am no better than the wicked Uriah Heep!

If Dora’s death turns out to be an affecting scene that brings tears to my eyes I am not sure if that will mean I can be forgiven for wishing her ill or that I am being punished for it by being made to cry in public (this being my commute book I am always in public while reading it). Perhaps I should start carrying a handkerchief I can throw over my face like they do in the book. No one will know what I am doing under that handkerchief! I might even frighten enough people that the transit police will show up to talk to me. Wouldn’t that be exciting? They’d haul me off for a psych eval if I tell them I am upset over my book. Would serve me right I guess for wishing Dora dead.

Filed under:

Books,

Charles Dickens,

In Progress

In a special Google Docs demonstration online, you can collaborate on a story with Charles Dickens, Friedrich Nietzsche, William Shakespeare, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Emily Dickinson and Edgar Allan Poe.

As you type your text into the demo box, these writers will add little flourishes and quotes to your story.

We created a short story with the help of Dickens and Nietzsche, click on the image embedded above to see the collaboration in action. Who will you write with?

New Career Opportunities Daily: The best jobs in media.

Dodger Terry Prachett

Dodger Terry Prachett

You know the Dodger from Oliver Twist, but this is a different side to him. One night, he's scavenging in the sewers (which is how he earns his living) when he witnesses a girl being beat. He comes to her aid and is immediately drawn into a different world. For Charles Dickens and Henry Mayhew see Dodger rescue the girl, and help further, by finding her food, medical attention, and a place to stay. Dodger wants to find the people who did this to her, and why, but the answers draw in the biggest political names of the day. Dodger is called Dodger for a reason, and these skills have allowed him to survive on London's streets thus far. Will they also help him survive in the city's finest drawing rooms?

I love Prachett's Dodger. His Dickens is also great. Some of the book is a little Shakespeare In Love but the mystery and action won't let you dwell on that for long. It's a fun read. Knowing your Dickens and your Victorian London personages will be helpful to fully appreciate it, but not necessary. I love the way Prachett paints Seven Dials, it's rough and tumble and a hard life, but the people who live there are real, and just trying to best they can. I also loved his take on Sweeney Todd and what was really going on there.

It doesn't speak to the LARGER TRUTHS that a lot of Prachett's work does, but it's also not as zanily weird, as it's firmly set in and grounded in historical facts and realities.

All in all I loved it. It's a great book that reminds me that I really do need to be reading more Prachett.

Book Provided by... my local library

Links to Amazon are an affiliate link. You can help support Biblio File by purchasing any item (not just the one linked to!) through these links. Read my full disclosure statement.

By: Alice,

on 12/24/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

authentic Christmas,

German Christmas markets,

German Christmas traditions,

Prince Albert,

Victorian Christmas traditions,

Windsor Castle,

World War I Christmas truce,

1800–1914,

godey,

History,

UK,

christmas,

christmas tree,

Victorian England,

Europe,

charles dickens,

queen victoria,

Neil Armstrong,

German History,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

oxford journals,

Add a tag

By Neil Armstrong

In recent years German Christmas markets have been promoted to the English as the epitome of a traditional and authentic Christmas. As germany-christmas-market.org.uk suggests, “if you’re tired of commercialism taking over this holiday period and would like to get right away for a real traditional and romantic Christmas market you might want to consider heading to Germany.” If a trip to Germany is impossible, a visit to a German Christmas market nearer to home is more feasible. Beginning with Lincoln in 1982, German Christmas markets have appeared in a number of British towns and cities.

The Queen’s Christmas tree at Windsor Castle published in the Illustrated London News, 1848, and republished in Godey’s Lady’s Book, Philadelphia in December 1850. via Wikimedia Commons.

One of the largest markets outside of the German-speaking world now takes place in Birmingham. In 2006 the

Daily Telegraph reported on this, commenting: “The late Queen (Victoria) would have almost certainly have been thinking of her beloved Albert, who is credited with introducing a number of German Christmas traditions to Britain, and who was

famously pictured with his then young bride and children beside a decorated tree — a custom which has since become an established norm the length and breadth of the country.” The link between Christmas and Germany automatically conjures the image of Prince Albert and the persistence of the myth of his role in the making of the modern English Christmas. Even before the death of the Prince Consort, children’s books such as

Peter Parley’s Annual were making unproblematic claims that the Christmas tree was “introduced” to Britain by Prince Albert. The royal Christmas tree at Windsor Castle was not the first to appear in England, though the appearance of the lithograph representation in the

Illustrated London News in 1848 undoubtedly did much to promote the custom.

Pinpointing the precise moment when a ritual practice appears in a new culture for the first time is often difficult. One way of examining the cultural transfer of customs is to look at the activities of artistic and literary elites. The first reference to German Christmas customs to appear in England was Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s account of the Christmas he spent in the German town of Ratzeburg in 1798. He described a Christmas Eve custom according to which children decorated the parlour with a yew bough, secured to a table, fastened little tapers to it, and then laid out presents for their parents (the children received their presents on Christmas Day). This account was published in the periodical The Friend in 1809, and was regularly reprinted during the first half of the nineteenth century. Reaction to it varied. Whilst Thomas de Quincey dismissed the “stage sentimentality” of a description which emphasized the potential of Christmas to promote much “weeping aloud for joy” on the part of parents touched by their children’s conduct, the poet Felicia Hemans took a great interest in German customs and attempted to imitate the tree ritual.

From 1840 a number of German Christmas stories for children were translated and published in England. These books emphasized the Christmas tree as being at the heart of a family-centred celebration, though by this time children were now the main recipients of seasonal gifts. The stories served as a reminder of the German origins of the Christmas tree, a fact which was often repeated when the tree was discussed in the popular press. For example, in his periodical Household Words, Charles Dickens described the tree as “that pretty German toy.” The majority of references to the German Christmas customs were not followed by any commentary of the significance of these origins. More occasionally, writers would eulogise the Germans as a simple, domestic and sentimental people, precisely the characteristics which were increasingly ascribed the festive English hearth. Consequently, the English were able to quickly adopt and naturalize the Christmas tree by making it palatable to the national story.

Despite growing Anglo-German rivalry in the years leading up to the First World War, the English view of the German Christmas persisted at the beginning of the twentieth century. It was played out in the press coverage of the famous Christmas truce of 1914, when British and German troops exchanged cigarettes and food, showed one another pictures of their families, and organised football matches. The best known image of the ceasefire appeared in the Illustrated London News in 1915, featuring a German soldier holding aloft a miniature tree as he approached two British soldiers; this was not only a symbol of peace but also of the values of domesticity and indulgence of childhood.

Whilst the Christmas truce has claimed a prominent place in the mythology of the Great War, it was followed by an abrupt change in Anglo-German relations, which were subsequently defined by anti-German propaganda, the legacy of Nazism, and post-war football rivalry. It is perhaps surprising then, that Germany should re-emerge as a spiritual home of the authentic and traditional Christmas in the English imagination. However, this is testimony to the inherent dynamic of nostalgia embedded in the festival. As I argue in Christmas in Nineteenth-Century England, laments for the loss of Christmases past have been present in festive discourse since the early seventeenth century.

German customs play an important role in the development of the English Christmas, but this argument can only be taken so far. After all, in the nineteenth century the English were no strangers to domesticity and the romanticization of childhood. Furthermore, Christmas is a transnational festival, and all modern Christmases are the product of a multiplicity of cultural transfers.

Neil Armstrong is Senior Lecturer in History at the University of Gloucestershire. He is the author of “England and German Christmas Festlichkeit, c.1800–1914″ in German History, which is available to read for free for a limited time.

German History is renowned for its extensive range, covering all periods of German history and all German-speaking areas. Every issue contains refereed articles and book reviews on various aspects the history of the German-speaking world, as well as news items and conference reports. It is an essential journal for German historians and of major value for all non-specialists interested in the field.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post German Christmas traditions appeared first on OUPblog.

By:

KidLitReviews,

on 12/22/2012

Blog:

Kid Lit Reviews

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Children's Books,

reviews,

classics,

Santa,

vampires,

gifts,

Scrooge,

rats,

board books,

Dracula,

Charles Dickens,

tombstones,

Holiday Book,

infants,

Christmas Present,

Christmas Past,

board book reviews,

5stars,

Alison Oliver,

Jennifer Adams,

5 heroes,

A Chiristmas Carol,

brown boots,

children's books reviews,

Christmas Future,

color primer,

counting primer,

green wreaths,

Little Timmy,

Mr. Marley,

nursery books,

purple drink,

silver bells,

silver chains,

Smith Gibb Publishing,

top hats,

Add a tag

Today we have two books from the Little Masters, Baby Lit® Books collection from publisher Gibbs Smith, author Jennifer Adams, and illustrator Alison Oliver. The first, A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens, is a coloring primer that will paint this week’s big day red and green. Then Bram Stoker’s Dracula, a counting primer, will put [...]

By: Alice,

on 12/21/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

olympics,

Titanic,

charles dickens,

alan turing,

odnb,

*Featured,

philip carter,

oxford dictionary of national biography,

oxford dnb,

Online Products,

Bill Cleland,

Captain Oates,

Captain Robert Scott,

Charles Dawson,

George Alcock,

Henry James Jones,

John Bellingham,

Piltdown Man,

Samuel Isaac,

Spencer Perceval,

Wallace Hartley,

History,

Biography,

james bond,

UK,

Add a tag

By Philip Carter

2012 — What a year to be British!

A year of street parties and river processions for the Jubilee; of officially the best Olympics ever; of opening and closing ceremonies; of Britons winning every medal on offer; of the (admittedly, not British) Tour de France, of David Hockney’s Yorkshire; and of a new James Bond film. Even a first tennis Grand Slam since the days when shorts were trousers and players answered to ‘Bunny’. If asked for the people of 2012 you’d obviously opt for Wiggins, Boyle, Farah, Ennis, Craig, Murray and, of course, Her Majesty the Queen, complete with parachute.

At the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography we too have delighted in these achievements. But, as our remit demands, we’ve also spent this year looking further back at some of the historical Britons celebrated or commemorated during 2012. As the year comes to a close, here are a few highlights — a look back, if you will, on looking back.

It’s been a strong year for anniversaries. We began in February with what’s proved the biggest and longest-running of these celebrations: the 200th anniversary of the birth of Charles Dickens about whom so much has been said and done in 2012. Other bicentenaries are available, however. In addition to the mighty ‘Boz’, the Oxford DNB includes a further 242 men and women born in 1812. A few did gain some recognition, notably the poets Robert Browning (born 7 May 1812) and Edward Lear, whose birthday fell a week later, but neither could compete with the Our Mutual Friend.

Any smaller and you were submerged in a Dickensian backwash. Thus only a handful of parties for the great Gothic architect Augustus Pugin (1 March) or the Russian-born radical and Anglophile, Alexander Herzen (6 April [New Style]), and probably nothing at all for these two gems from the ODNB list. First, Samuel Isaac (1812-1886) who, despite having ‘no engineering experience’, accepted an invitation to undertake and underwrite the building of the Mersey Tunnel — what’s more successfully (it opened in February 1885). Then there’s Henry James Jones (1812-1891), Bristol baker and ‘the inventor of self-raising flour’ — surely a man deserving a little more recognition in the year of Boz. No Henry James Jones (or yeast) means no fluffy loaf, however Great your Expectations.

Popular anniversaries often highlight artistic or cultural, rather than science-related, episodes from our past. 2012 was a bit different in that it saw celebrations (in June) for the centenary of the mathematician, Alan Turing (1912-1954). Turing’s appeal is due in part to the near universal reach of his work — even if the details of The Turing Machine, and later developments in computer science, leave most of us baffled. There’s also his wartime association with Bletchley Park where he spearheaded the breaking of the German Enigma and Fish codes. But Turing also catches the imagination for his (then) unusual openness towards his sexuality, his arrest and controversial punishment for indecency, his curious death, and the ongoing campaign to have him granted a posthumous pardon.

Turing was rightly deserving of the anniversary events held in 2012, though — as the Oxford DNB again shows — he wasn’t alone among scientific centenarians. In fact, the dictionary offers a further 29 men and women born in 1912 and now remembered for their contributions to scientific and medical fields. They include some remarkable lives: among them the astronomer George Alcock (born 28 August) — who discovered five comets (a British record) and boasted a photographic memory of 30,000 stars — and cardiologist Bill Cleland (30 May), the pioneer of open heart surgery in Britain in the early 1950s. Centenary science (albeit of a much less robust kind) is also marked this month, indeed this week, with the 100th anniversary of the public unveiling of Piltdown Man. Discovered in Sussex, these bone fragments were dated by their finder, Charles Dawson, to 4 million BC and identified as the ‘missing link’ between apes and man. The announcement, made on 18 December 1912, caused a sensation. For four decades Piltdown Man — or Eoanthropus dawsoni, Dawson’s Dawn Man — enjoyed the status of Europe’s oldest known human. Then, in the 1950s, Piltdown was revealed for what he really was: parts of a relatively recent human skull mingled with bones from a small orangutan. In December, therefore, we remember a 100 year-old hoax.

2012 was also a year for looking back at some dramatic, indeed shocking, events. Charles Dickens was just three months old when, on 11 May 1812, the prime minister Spencer Perceval was shot and killed in the Commons lobby — the first and only British premier to suffer this fate. His assailant was John Bellingham, a bankrupt commercial agent who was arrested, tried, and hanged within the week.

On 18 May 1912, exactly 100 years after Bellingham’s execution, 30,000 people gathered in Colne, Lancashire, for the funeral of a local man, Wallace Hartley, a former ship’s musician. So many gathered because that ship was the RMS Titanic, captained by Edward Smith who with Hartley, and more than 1500 others, lost their lives on 15 April 1912. The Titanic disaster — undoubtedly the anniversary event of the year — came within weeks of an equally celebrated episode in popular histories of Britishness. On 19 March 1912 Captain Robert Scott and his two surviving companions pitched their tent for the final time. It was three months since their ‘defeat’ at the South Pole, and three days since their fellow explorer Captain Oates had walked to his death. The men got no further, with Scott the last to die on about 29 March. Looking back from 2012 the tragedies of ‘Scott of the Antarctic’ and the Titanic come in quick succession, a severe blow to Edwardian self-confidence seemingly delivered in the spring of 1912. A centenary ago the chronology was, of course, a little different: not until November 1912 did a search team confirm the deaths of Scott and his party, and it took a further three months for news of this disaster to reach London.

In the coming decades, delays of this kind would become a thing of the past. And last month the BBC marked the 90th anniversary of the reason why: the institution’s first radio broadcast, an event that would soon bring new sounds, voices, opinions, and information into millions of homes. At the helm on 14 November 1922 was the imperious John Reith, manager of what was then the British Broadcasting Company. At the microphone, Arthur Burrows, who announced the results of the general election: Mr Bonar Law 332, David Lloyd George 127.

If you missed Dickens, Turing, Perceval, and Piltdown Man, and would like to get involved there is still time. Between now and the year end why not hold a do-it-yourself celebration for the author of Self-Help, Samuel Smiles (born 23 December 1812)? Or throw a ‘happening’ for the centenary of Birmingham surrealist, Conroy Maddox (27 December)? In a striking coming together of dates, 12 December is also the 150th anniversary of J. Bruce Ismay’s birth. The owner of the White Star shipping line, Ismay is now remembered for his controversial escape from his greatest ship — the RMS Titanic.

And the future? A quick search of the Oxford DNB reveals many reasons to celebrate and commemorate in 2013. Take, for instance, the quatercentenary of library founder Thomas Bodley; the bicentenary of Pride and Prejudice; the 150th anniversary of the London Underground; 100 years of British film censorship; 50 years since Kim Philby’s flight to Russia; Britain’s 40 years in the European Union; or 20 years since the death of Audrey Hepburn. And that’s just January.

Philip Carter is Publication Editor of the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. The Oxford DNB online is freely available via public libraries across the UK. Libraries offer ‘remote access’ allowing members to log-on to the complete dictionary, for free, from home (or any other computer) twenty-four hours a day. In addition to 58,000 life stories, the ODNB offers a free, twice monthly biography podcast with over 165 life stories now available (including the lives of Alan Turing, Piltdown Man, Wallace Hartley, and Captain Scott). You can also sign up for Life of the Day, a topical biography delivered to your inbox, or follow @ODNB on Twitter for people in the news.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only British history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Looking back on looking back: history’s people of 2012 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 12/18/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

OWCs,

roast goose,

cratchit,

ebeneezer scrooge,

cratchits,

Food,

Literature,

Christmas,

Victorian,

christmas books,

christmas dinner,

scrooge,

OWC,

Food & Drink,

charles dickens,

pudding,

Oxford World's Classics,

a christmas carol,

Humanities,

tiny tim,

*Featured,

Arts & Leisure,

Add a tag

Following yesterday’s recipe for roast goose by Mrs Beeton, here’s that classic Christmas dinner portrayed by Charles Dickens in the famous scene from A Christmas Carol. Here Ebeneezer Scrooge watches with the Ghost of Christmas Present as the Cratchit family sits down to roast goose and Christmas pudding.

‘And how did little Tim behave?’ asked Mrs Cratchit, when she had rallied Bob on his credulity, and Bob had hugged his daughter to his heart’s content.

‘As good as gold,’ said Bob, ‘and better. Somehow he gets thoughtful, sitting by himself so much, and thinks the strangest things you ever heard. He told me, coming home, that he hoped the people saw him in the church, because he was a cripple, and it might be pleasant to them to remember upon Christmas Day, who made lame beggars walk, and blind men see.’

Bob’s voice was tremulous when he told them this, and trembled more when he said that Tiny Tim was growing strong and hearty.

Bob’s voice was tremulous when he told them this, and trembled more when he said that Tiny Tim was growing strong and hearty.

His active little crutch was heard upon the floor, and back came Tiny Tim before another word was spoken, escorted by his brother and sister to his stool before the fire; and while Bob, turning up his cuffs — as if, poor fellow, they were capable of being made more shabby — compounded some hot mixture in a jug with gin and lemons, and stirred it round and round and put it on the hob to simmer; Master Peter, and the two ubiquitous young Cratchits went to fetch the goose, with which they soon returned in high procession.

Such a bustle ensued that you might have thought a goose the rarest of all birds; a feathered phenomenon, to which a black swan was a matter of course — and in truth it was something very like it in that house. Mrs Cratchit made the gravy (ready beforehand in a little saucepan) hissing hot; Master Peter mashed the potatoes with incredible vigour; Miss Belinda sweetened up the apple-sauce; Martha dusted the hot plates; Bob took Tiny Tim beside him in a tiny corner at the table; the two young Cratchits set chairs for everybody, not forgetting themselves, and mounting guard upon their posts, crammed spoons into their mouths, lest they should shriek for goose before their turn came to be helped. At last the dishes were set on, and grace was said. It was succeeded by a breathless pause, as Mrs Cratchit, looking slowly all along the carving knife, prepared to plunge it in the breast; but when she did, and when the long expected gush of stuffing issued forth, one murmur of delight arose all round the board and even Tiny Tim, excited by the two young Cratchits, beat on the table with the handle of his knife, and feebly cried Hurrah!

There never was such a goose. Bob said he didn’t believe there ever was such a goose cooked. Its tenderness and flavour, size and cheapness, were the themes of universal admiration. Eked out by apple-sauce and mashed potatoes, it was a sufficient dinner for the whole family; indeed, as Mrs Cratchit said with great delight (surveying one small atom of bone upon the dish), they hadn’t ate it all particular, were steeped in sage and onion to the eyebrows! But now, the plates being changed by Miss Belinda, Mrs Cratchit left the room alone — too nervous to bear witness — to take the pudding up and bring it in.

Suppose it should not be done enough! Suppose it should break in turning out! Suppose somebody should have got over the wall of the back-yard, and stolen it, while they were merry with the goose — and supposition at which the two young Cratchits became livid! All sorts of horrors were supposed.

Hallo! A great deal of steam! The pudding was out of the copper. A smell like a washing-day! That was the cloth. A smell like an eating-house and a pastrycook’s next door to each other, with a laundress’s next door to that! That was the pudding! In half a minute Mrs Cratchit entered — flushed by smiling proudly — with the pudding, like a speckled cannon-ball, so hard and firm, blazing in half of half-a-quartern of ignited brandy, and bedight with Christmas holly stuck into the top.

Oh, a wonderful pudding! Bob Cratchit said, and calmly too, that he regarded it as the greatest success achieved by Mrs Cratchit since their marriage. Mrs Cratchit said that now the weight was off her mind, she would confess she had her doubts about the quantity of flour. Everybody had something to say about it, but nobody said or thought it was at all a small pudding for a large family. It would have been flat heresy to do so. Any Cratchit would have blushed to hint at such a thing.

At last the dinner was all done, the cloth was cleared, the hearth swept, and the fire made up. The compound in the jug being tasted, and considered perfect, apples and oranges were put upon the table, and a shovel-full of chestnuts on the fire. Then all the Cratchit family drew round the hearth, in what Bob Cratchit called a circle, meaning half a one; and at Bob Cratchit’s elbow stood the family display of glass. Two tumblers, and a custard-cup without a handle.

These held the hot stuff from the jug, however, as well as golden goblets would have done; and Bob served it out with beaming looks, while the chestnuts on the fire sputtered and cracked noisily. Then Bob proposed:

‘A Merry Christmas to us all, my dears. God bless us!’ Which all the family re-echoed.

‘God bless us every one!’ said Tiny Tim, the last of all.

A Christmas Carol has gripped the public imagination since it was first published in 1843, and it is now as much a part of Christmas as mistletoe or plum pudding. The Oxford World’s Classics edition, edited by Robert Douglas-Fairhurst, reprints the story alongside Dickens’s four other Christmas Books: The Chimes, The Cricket on the Hearth, The Battle of Life, and The Haunted Man.

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Reproduced from a c.1870s photographer frontispiece to Charles Dicken’s A Christmas Carol. By Frederick Barnard (1846-1896). Digital image from LIFE. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post Christmas dinner with the Cratchits appeared first on OUPblog.

By:

Heidi MacDonald,

on 12/12/2012

Blog:

PW -The Beat

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reviews,

Comics,

Dark Horse,

Charles Dickens,

A Christmas Carol,

John Milton,

Dante,

Jill Thompson,

Mike Mignola,

Evan Dorkin,

Top Comics,

Hellboy in Hell,

House of Fun,

Milk and Cheese,

Paradise Lost,

Add a tag

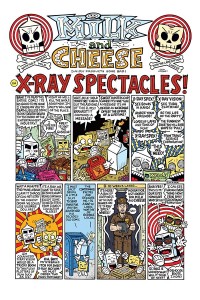

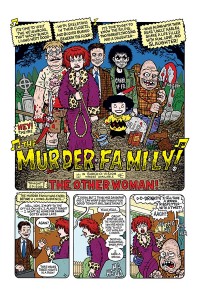

December has been a big month for Dark Horse, with two much anticipated books finally hitting the shelves: Mike Mignola’s HELLBOY IN HELL #1 and Evan Dorkin’s HOUSE OF FUN. Coincidentally, both books signal the return of their respective creators to solo work; for Mignola, it’s been 7 years since he drew and scripted a HELLBOY comic, and for Dorkin, it’s been 6 since a solo issue appeared. For Mignola and Dorkin fans, this alone is enough to drive people to their comic dealers as soon as they unlock the doors. The iconic content weighs in as the second frenzy-inducing factor.

The HELLBOY series, and indeed, the HELLBOY universe complete with B.P.R.D., ABE SAPIEN and the lot, has been building steadily toward the HELL arc with plenty of conjecture over what exactly Hellboy’s role will be in the end of the world. THE WILD HUNT arc revealed Hellboy’s role as the rightful heir of the throne of Britain via intricate mythological storylines, only to culminate in what seemed like the worst fate imaginable for fans: Hellboy’s death by having his heart ripped out. No amount of hinting from Mignola and Dark Horse that this was not the end for the well-meaning devil could really erase the sense that Hellboy’s story was drawing to a close, and it was a bitter sweet revelation. Fans want to know how his story ends, but of course do not want his story to end at all. At New York Comic Con 2012 in a panel devoted to HELLBOY IN HELL, Mignola painted a cheerier picture. It’s been a long road for Mignola, and Hellboy, and tying up all the loose ends, the meaningful details, and the wider apocalyptic thrust of the B.P.R.D. series must be a logistical nightmare, and one which Mignola felt very keenly must be done well, and satisfyingly, or not at all.Some of Mignola’s prophecies at NYCC 2012 have already come to pass in issue #1. For one thing, characters who die in HELLBOY “become more interesting”.

That’s no surprise to readers, who have watched Hellboy battle ghosts, monster, and demon-princes from the Netherworld time and again, but leave it to Mignola to find a way to reverse the typical encounter paradigm. With Hellboy himself dead, he faces the dead or the never living on their own turf, turf which theoretically Hellboy finds native. That very fact, however, provides unique dramatic tension. It’s the equivalent of throwing Batman into Arkham Asylum with the inmates he has personally incarcerated over the years. Many of the dead in Hell were sent there by Hellboy and are burning for a little payback. This is essentially a new situation for Hellboy, and therefore a treat for faithful readers. What’s surprising is that even Hellboy’s going to need a little help to deal with his descent into Hell. Mignola has always been masterful at sculpting folklore traditions to suit the needs of his stories, but keeping interpretation loose enough to allow him to tell his own tale. HELLBOY IN HELL is bound to be shaped by literary and folklore traditions about the underworld, and most cultures have a version of this descent in their collective memories. There is usually a guide, for instance, a Virgil to guide Dante. Here Sir Edward, corpse-like with a creepy mask, volunteers, employing necromantic skills to protect Hellboy from the immediate wrath of enemies. Leave it to Mignola to manage to bring in a haunting puppet-show and thematically relevant lines from Charles Dickens’ A CHRISTMAS CAROL this close to Christmas to strike a little fear into the hearts of readers.

No good HELLBOY issue functions without a knock-down, drag-out fight, and this is no exception, only this time, Hellboy has nearly met his match in Eligos, a “Duke and Knight of the Order of the Fly”, whom Hellboy cast into the pit previously. Perhaps the biggest surprise of the issue is when readers learn that these encounters are taking place in “The Abyss”, only “the outer edge” of Hell. It certainly makes you wonder what grander revelations are to come, especially since the next issue is entitled “Pandaemonium”, which is the capitol of Hell in Milton’s PARADISE LOST, the gathering place of Hell’s elite. Mignola’s return to HELLBOY does not disappoint, from it’s lavish full page spreads of “The Abyss” to the sepulchral eeriness of the puppet show, but if there are any drawbacks, it’s only that the issue is a very quick read due to limited dialogue in a comic that shows astonishing things rather than tells about them. The visual details that remain unexplained, however, invite readers to start putting the pieces of the puzzle together on Hellboy’s final journey, and I don’t think you’ll hear many complaints. HELLBOY in HELL returns to the grandeur of earlier HELLBOY stories with Mignola as artist and writer in an suitably majestic way, reminding readers that all along, Hellboy’s story has been epic.

Evan Dorkin’s HOUSE OF FUN couldn’t be more different in format than HELLBOY IN HELL; HELLBOY’s expansive page and panel layouts, conjuring the voids of the netherworld meet a comic so packed with art and storytelling that no reader could accuse HOUSE OF FUN of being less than its worth in cover price. In fact, HOUSE OF FUN is like getting an entire collected edition in one shot, reminding readers what they love about Dorkin: his work is a wild informational overload via both imagery and language. Dorkin’s never been absent from the indie comics scene, but the past year has seen a steady build in press for him, from the award winning BEASTS OF BURDEN with Jill Thompson to the repeatedly back-ordered hardcover edition of MILK AND CHEESE, and HOUSE OF FUN strikes another high-note for fans. This one-shot collects several shorts that originally appeared in DARK HORSE PRESENTS #11-12, but Dorkin’s avatar on the inside cover also warns readers, “It’s been awhile since I made a bunch of comics all by myself like an immature adult, so I hope you like reading them as much as I liked making them! Yeah.”. I’ll go out on a limb and speak for readers by saying, please, Dark Horse, allow Dorkin to be an immature adult as much as possible if this is the result.

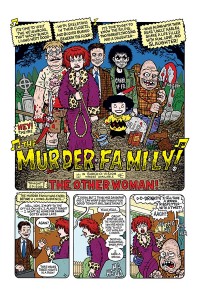

The MILK and CHEESE segments of the comic alone are worth the cover price of the book, maybe even just the opening page wherein the due order “X-Ray Spex” and attain superpowers of the utmost degree, declaring “Our eyes now have mad skillz!” and they “can see through everything now! Feng Shui! Scientology! Family Guy!”. Unsurprisingly, violence ensues, but not without plenty of psychological commentary on the power of suggestion. THE MURDER FAMILY “living next door” takes readers deep into the dark heart of suburbia with household chores like “dusting, vacuuming, embalming” and fears that Dad’s “been going out killing with another woman!”. The “fun” compressed into this issue includes “The Haiku of the Ancient Sub-Mariner”, “Broken Robot”, and even “Dr. Who: the 25th Doctor” in unrestrained satire of pop culture storytelling grounded in detailed, and biting observation.

“The Eltingville Comic Book. Science Fiction, Fantasy, Horror, and Role Playing Club” appear (and that must be one of the longest names of a fan group to appear in comics, though certainly accurate of real-life counterparts) to deliver weighty prose commentary on zombie-fever in the media, for instance, Gary’s rejoinder, “Surely, you are high. Everybody knows slow-moving zombies are lame and boring and about as scary as Scooby-Doo. Why do you think the base locomotion of the modern film zombie has steadily been on the rise?”. You could call this meta-commentary on the medium, since the club members themselves appear as zombies on a zombie walk, but “meta” disappears in HOUSE OF FUN within the increasingly intricate layers of sub-text. This one-shot also contains an added bonus for fans: Dorkin’s sketches for a comic that he once planned to contain many of the included stories, DORK #12, as well as a few of his zombie layouts.

While HELLBOY IN HELL #1 encourages re-reading to scour for hints and details that may indicate the direction of future issues or help tie #1 to the vast and varied HELLBOY past, HOUSE OF FUN will have fans re-reading to pick apart the corresponding gags between the mile-a-minute text and the elaborately dense panels. One thing is certain: neither comic will easily end up in a dollar bin. These are keepers, milestones for both Mignola and Dorkin, and are the likely candidates to turn up again and again at signings in the near future. Snag your copies while you can.

Hannah Means-Shannon writes and blogs about comics for TRIP CITY and Sequart.org and is currently working on books about Neil Gaiman and Alan Moore for Sequart. She is @hannahmenzies on Twitter and hannahmenziesblog on WordPress.

By: Nicola,

on 12/12/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Poetry,

Literature,

Psychology,

charles dickens,

200th anniversary,

Humanities,

nineteenth century,

victorian poet,

the poet's mind: the psychology of victorian poetry 1830-1870,

the ring and the book,

browning’s,

oddness,

*Featured,

dickens 2012,

@drgregorytate,

alfred tennyson,

bicentary,

browning society,

gregory tate,

robert browning,

browning,

Add a tag

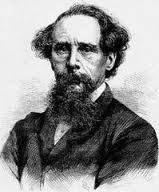

By Gregory Tate

This year marked the bicentenary of the birth of the Victorian poet Robert Browning in 1812, although this news might come as something of a surprise. The bicentenary of Browning’s contemporary Charles Dickens was celebrated with so many exhibitions, festivals, and other events that an official Dickens 2012 group was set up to co-ordinate and keep track of them all. The writings of Alfred Tennyson, Browning’s (consistently more popular) rival, also cropped up in some high-profile places throughout the year. But although academic specialists and other Browning enthusiasts organised conferences and special publications in 2012, media commentators and cultural institutions remained almost wholly silent about the Browning anniversary.

There are many possible reasons for this silence. There’s the issue of religion: Browning’s robust Christian faith, and his love of abstruse theological speculation, are perhaps less congenial to twenty-first-century tastes than the yearning doubt of Tennyson or the pious sentimentality of Dickens. Browning’s habit of writing poems about arcane subjects (such as the thirteenth-century troubadour Sordello or the sixteenth-century alchemist Paracelsus) might also alienate readers. The reason might, however, be something even more fundamental: Browning’s poetry is difficult, and discomfiting, to read. When Browning was buried in Poets’ Corner in Westminster Abbey on 31 December 1889, Henry James wrote that “a good many oddities and a good many great writers have been entombed in the Abbey; but none of the odd ones have been so great and none of the great ones so odd.” For James, Browning’s oddness was an essential part of his poetic achievement. Today, it seems, the general view (if there is a general view on him at all) is that his oddness precludes greatness.

For most of his life, Browning’s oddness was seen by his Victorian contemporaries as the key characteristic of his writing. John Ruskin, for example, wrote to the poet in 1855 to describe the poems in his new book Men and Women as “absolutely and literally a set of the most amazing Conundrums that ever were proposed to me.” Browning’s reply to Ruskin is significant, because it suggests that his difficult style is central to the goals of his poetry: “I know that I don’t make out my conception by my language; all poetry being a putting the infinite within the finite.” This definition of poetry was closely tied to Browning’s views on psychology: throughout his career he was preoccupied with the question of how to fit what he saw as the infinite capacities of the human mind into the finite media of language and poetic form. His answer was to adopt a knotty, convoluted, and tortuous syntax which articulated the difficulty, but also the necessity, of conveying the workings of the mind through the more or less inadequate tools of language.

For most of his life, Browning’s oddness was seen by his Victorian contemporaries as the key characteristic of his writing. John Ruskin, for example, wrote to the poet in 1855 to describe the poems in his new book Men and Women as “absolutely and literally a set of the most amazing Conundrums that ever were proposed to me.” Browning’s reply to Ruskin is significant, because it suggests that his difficult style is central to the goals of his poetry: “I know that I don’t make out my conception by my language; all poetry being a putting the infinite within the finite.” This definition of poetry was closely tied to Browning’s views on psychology: throughout his career he was preoccupied with the question of how to fit what he saw as the infinite capacities of the human mind into the finite media of language and poetic form. His answer was to adopt a knotty, convoluted, and tortuous syntax which articulated the difficulty, but also the necessity, of conveying the workings of the mind through the more or less inadequate tools of language.

Browning’s approach is exemplified in what is arguably his greatest poem, The Ring and the Book (1868-1869), a psychological epic which recounts the events of a seventeenth-century murder case from nine different perspectives. Browning sets out to integrate these conflicting perspectives into an authoritative and morally educational account of the murder, describing them as:

The variance now, the eventual unity,

Which make the miracle. See it for yourselves,

This man’s act, changeable because alive!

Action now shrouds, now shows the informing thought.

The poem’s concern is not with the murder itself, “this man’s act”, but with tracing “the informing thought,” the motive behind the act. This poetic analysis of thought, Browning argues, enables the synthesis of conflicting accounts into an “eventual unity,” and the dense style of his verse is a key element of this process. “Art,” he states “may tell a truth / Obliquely, do the thing shall breed the thought.” By testing and confounding his readers, Browning’s difficult (and odd) poetry invites them to think carefully about the minds of other people, breeding new thoughts and telling oblique truths.

In The Ring and the Book Browning addresses the “British Public, ye who like me not.” The publication of this poem, however, marked a sea change in Victorian opinions of the poet. In the 1870s and 1880s his writing was admired simultaneously for its evident Christianity and its intellectual richness, and he was venerated as a sage and a moral teacher by the Browning Society which was founded in 1881 to study and champion his work. He was also celebrated, by Henry James and by Modernists such as Ezra Pound, as (in James’s words) “a tremendous and incomparable modern.” In 2012, though, Browning’s modernity and relevance have not been sufficiently emphasised. This is a shame, because, in his psychological sophistication and in his awareness of the complexities and limitations of language, he still has truths to tell to the British public, who like him not. Those truths, and Browning’s poems, might be oblique and difficult, but they’re worth the effort.

Gregory Tate is Lecturer in English Literature at the University of Surrey. His book, The Poet’s Mind: The Psychology of Victorian Poetry 1830-1870, was published by OUP in November 2012. You can follow him on Twitter @drgregorytate.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Robert Browning. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Robert Browning in 2012 appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 12/1/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

robert douglas-fairhurst,

Editor's Picks,

*Featured,

podularity,

Audio & Podcasts,

miss havisham,

OWCs,

magwitch,

pip,

dickens3,

podcast,

Literature,

fiction,

Victorian,

audio,

Multimedia,

haunted,

OWC,

charles dickens,

expectations,

Oxford World's Classics,

dickens,

great expectations,

douglas,

Humanities,

english literature,

Add a tag

On 1 December 1860, Charles Dickens published the first installment of Great Expectations in All the Year Round, the weekly literary periodical that he had founded in 1859. Perhaps Dickens’s best-loved work, it tells the story of young Pip, who lives with his sister and her husband the blacksmith. He has few prospects for advancement until a mysterious benefaction takes him from the Kent marshes to London. Pip is haunted by figures from his past — the escaped convict Magwitch, the time-withered Miss Havisham, and her proud and beautiful ward, Estella — and in time uncovers not just the origins of his great expectations but the mystery of his own heart.

A powerful and moving novel, Great Expectations is suffused with Dickens’s memories of the past and its grip on the present, and it raises disturbing questions about the extent to which individuals affect each other’s lives. Below is a sequence of podcasts with Robert Douglas-Fairhurst, editor of the Oxford World’s Classics edition of Great Expectations, recorded by George Miller of Podularity.

Title page of first edition of Great Expectations by Charles Dickens, 1861