new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Obituaries, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 51 - 75 of 312

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Obituaries in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

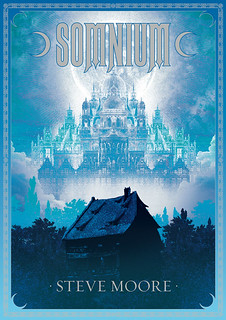

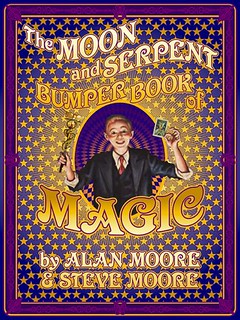

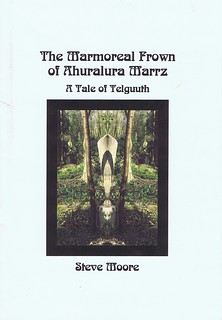

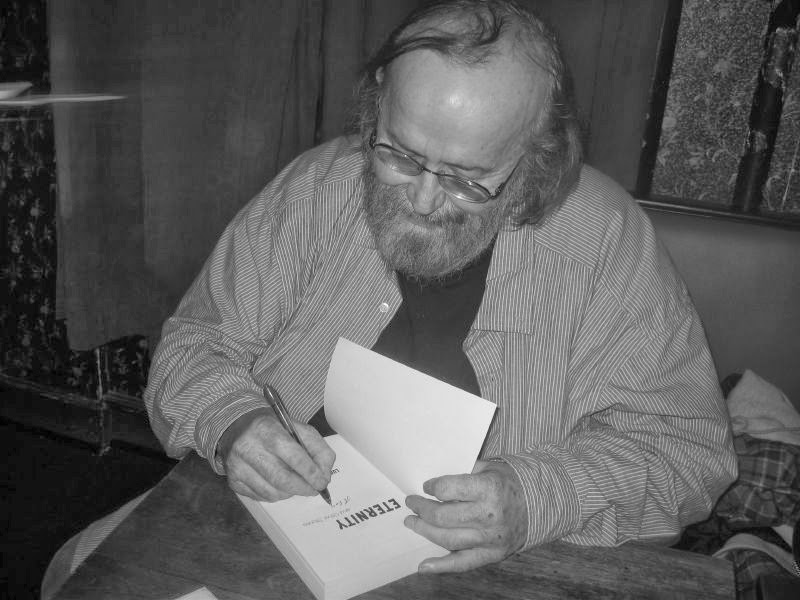

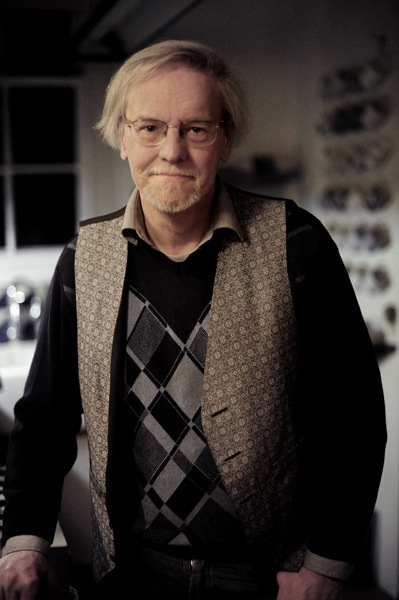

Here’s the second part of my interview with Steve Moore, with more to follow. The first part can be found here, along with some explanation of how the interview came about.

PÓM: Did you go to many SF cons?

SM: Only two or three, I think … at least, that’s all I remember! They were all in the mid-60s, and after that I started losing interest in SF in favour of comics. And by the end of the decade I’d pretty much lost interest in conventions in general.

PÓM: You were involved in the first British comics conventions as well, I believe?

PÓM: You were involved in the first British comics conventions as well, I believe?

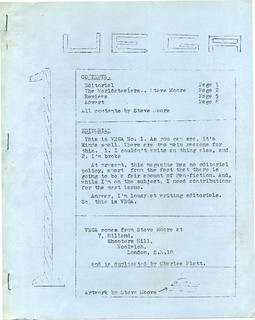

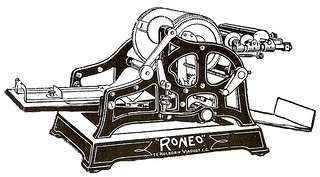

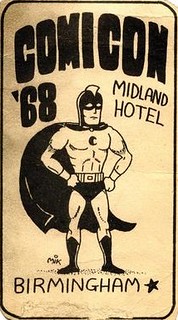

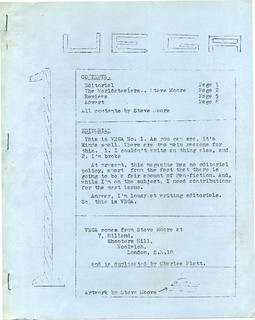

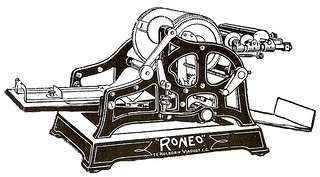

SM: The first two, yes. The first one was at the Midland Hotel in Birmingham in August 1968, and the organising committee was Phil Clarke, his then girlfriend Kay Hawkins and myself. Being on the spot in Birmingham, Phil and Kay did most of the actual organising, while I helped out with publicity (mainly through Odhams’ Power Comics line) and printing with my ‘trusty’ Roneo. I’d already printed off a couple of personal sales-lists for Phil called The Comic Fan, which we then turned into two issues of The Comic Fan Special, which was our news-bulletin, and also listed comics (mainly Phil’s) that were being sold to raise money for expenses. Looking at the second issue of this, I see there was going to be a convention booklet, which I wasn’t going to be printing, but if I still have a copy of that, it must be somewhere in the loft.

I remember very little about that first convention (for many years I thought it had been in 1967!), though I recall the hotel as being big, old and gloomy. I think there may have been about 50 or 60 people there, and a few ‘non-attending’ members. There was the usual stuff: movies, panel discussions, auctions, but I only know this from looking at the bulletin, not from memory! It was all very small scale, and modelled on what we knew of SF conventions, but we had a good time and that was how it all started. I’m afraid I’m one of the guilty men …

I remember very little about that first convention (for many years I thought it had been in 1967!), though I recall the hotel as being big, old and gloomy. I think there may have been about 50 or 60 people there, and a few ‘non-attending’ members. There was the usual stuff: movies, panel discussions, auctions, but I only know this from looking at the bulletin, not from memory! It was all very small scale, and modelled on what we knew of SF conventions, but we had a good time and that was how it all started. I’m afraid I’m one of the guilty men …

Anyway, I obviously hadn’t had enough, as I got involved with the second one as well, at the Waverley Hotel in London, the following year. This time the committee was Frank Dobson, Derek Stokes, Alan Willis (of whom I remember nothing whatever), and myself. It was bigger, more organised … and again I remember virtually nothing about it, though this time that was mainly because I was in a blind, exhausted panic through most of the weekend, trying to make sure that everything worked. And that was enough organising for me. I went to the third in Sheffield, and I think to another one at the Waverley. And then I’d really had enough of conventions in general, and entered my ‘reclusive phase’ … which has lasted for about 40 years so far!

->PÓM: You have been a recluse, apparently, ever since then. Did you just decide it all wasn’t for you, or what happened?

SM: I’m basically a recluse as far as comic conventions and personal appearances go, that’s all. I have a number of very close friends, some going back decades, who I like to see as often as possible, and I’m certainly not agoraphobic in terms of not wanting to leave the house! But by the time we got to the comic cons I was working in the business, which made me a bit of a ‘celebrity’, and I’ve never had any interest in that. And the idea of being in a large room full of people who know me, when I don’t know them, just makes me uncomfortable. Besides, by 1972 I’d gone freelance, and I made a conscious decision to stop reading other people’s comics so I could develop my own style, so what was the point of going to a convention to discuss things I was no longer familiar with or interested in? By then I just wasn’t ‘a comic fan’ any more. So I just withdrew from that whole scene.

PÓM: Do you remember who attended those early comic cons?

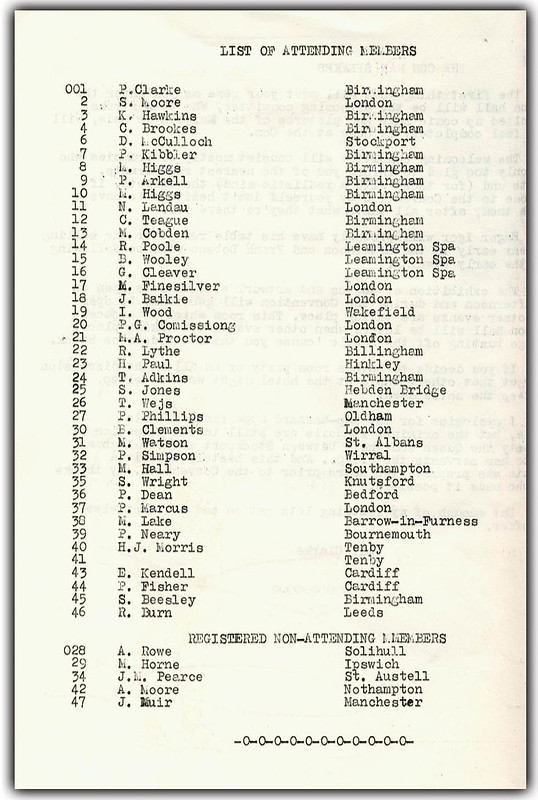

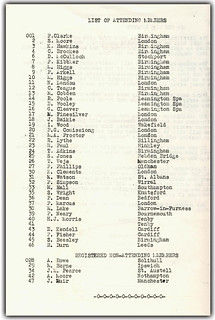

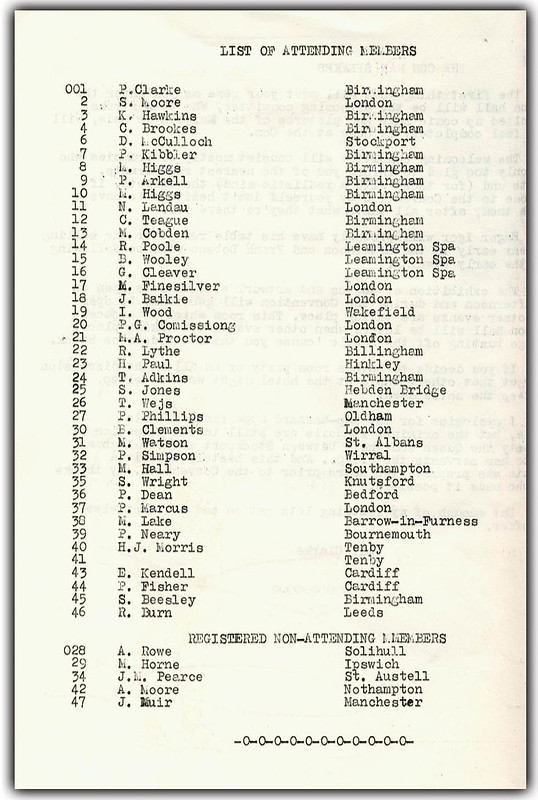

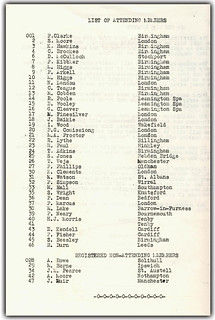

SM: Well, looking at the membership list published in an issue of The Comic Fan Special, I see that a number of notable fans were due to be at the first one, like Dave McCullough, Nick Landau, Pete Phillips and Paul Neary. But if you’re asking me who I remember, apart from Phil, Kay and myself, it basically comes down to Jim Baikie, who was living not far from me in South Norwood at the time, and with whom I developed a fairly close friendship, before he moved back to the Orkneys.

The membership list for the first Comicon

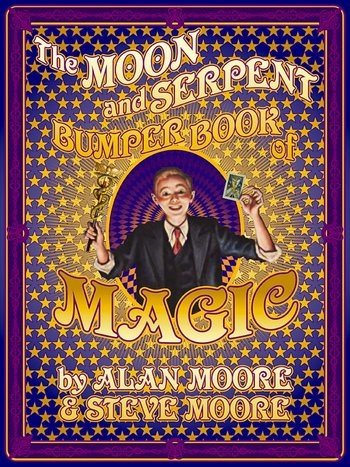

As for the second one, like I said, it was pretty much of a blur. But among those there were Alan Moore, Steve Parkhouse, Barry Smith and Bob Rickard, the future founder of Fortean Times, none of whom I had as much time to talk to as I would have liked. I also remember shouting at a young kid called Dave Womack, who was making a rather loud nuisance of himself throughout the weekend, and being baffled by an Edgar Rice Burroughs fan called Frank Westwood, who asked me where he could find a Roman Catholic church on the Sunday morning; something which had simply never occurred to me to find out (and which, at the time, I actually thought was pretty weird; after all, when there was a comic book convention going on, why would you want to go to church?).

PÓM: What do you think drove you to want to produce all those fanzines?

SM: Essentially, it was what fans did in those days. There was no internet, no blogs, so if you wanted to do stuff about comics, you did fanzines. It was a mushroom industry in the late 60s, early 70s, especially as cheap offset printing started to come in. Everybody seemed to be doing it … some people were doing four or five at once, on different topics, and the adzines were both offering comics for sale, but advertising all the various fanzines as well. And fanzine editors would trade both copies and adverts with one another, as well as offering space for articles, etc., that you might not have wanted to do in your own fanzine. In many ways it was a bit like an early version of the internet, but done with printed paper, envelopes and postage stamps. It’s how we kept in touch.

As I’ve said, I was mainly interested in getting new material together, rather than articles, and I don’t think I wrote much about comics, preferring to contribute stuff to magazines that fringed away from comics into fantasy and underground material, like John Muir’s Crucified Toad. A strange man who, I’m told, ended up in some sort of shady business in the East, and got himself murdered for it. Or so I’m told.<-

As I’ve said, I was mainly interested in getting new material together, rather than articles, and I don’t think I wrote much about comics, preferring to contribute stuff to magazines that fringed away from comics into fantasy and underground material, like John Muir’s Crucified Toad. A strange man who, I’m told, ended up in some sort of shady business in the East, and got himself murdered for it. Or so I’m told.<-

PÓM: Wasn’t it around that time that you first started working in comics yourself?

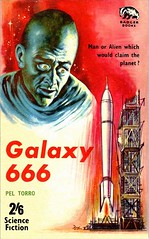

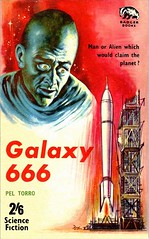

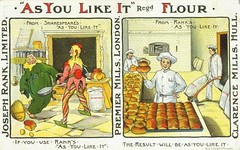

SM: That’s right. If we backtrack to autumn 1966, I’d been stuck in the laboratory job for a year. So I decided to write letters to half a dozen comics publishers in London (yes, there were actually that many comics publishers in those days) and simply asked them if they had any jobs. I got polite replies (‘no’) from a couple of them, and one offer of an interview, from John Spencer & Co., the publishers of Badger Books, who at the time were publishing a couple of really bad black-and-white superhero books, which in the end only lasted a couple of issues each. So I made my way over to West London one evening to their tiny premises, which I think was pretty much one office and a storeroom, but it turned out they basically wanted a warehouseman, which really wasn’t what I was looking for. So I knuckled down to the flour samples and sulphuric acid fumes again.

SM: That’s right. If we backtrack to autumn 1966, I’d been stuck in the laboratory job for a year. So I decided to write letters to half a dozen comics publishers in London (yes, there were actually that many comics publishers in those days) and simply asked them if they had any jobs. I got polite replies (‘no’) from a couple of them, and one offer of an interview, from John Spencer & Co., the publishers of Badger Books, who at the time were publishing a couple of really bad black-and-white superhero books, which in the end only lasted a couple of issues each. So I made my way over to West London one evening to their tiny premises, which I think was pretty much one office and a storeroom, but it turned out they basically wanted a warehouseman, which really wasn’t what I was looking for. So I knuckled down to the flour samples and sulphuric acid fumes again.

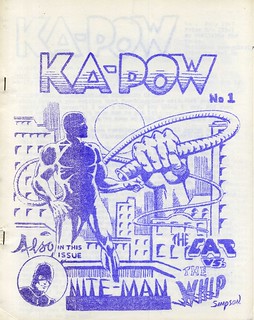

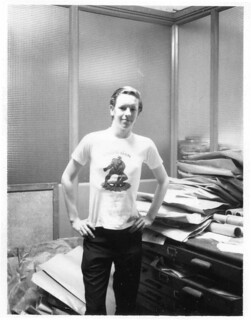

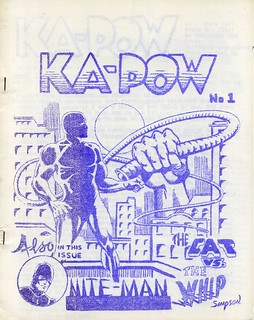

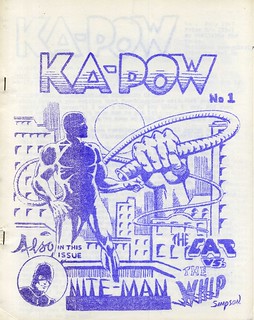

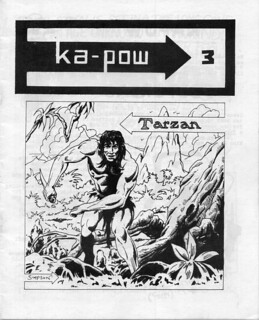

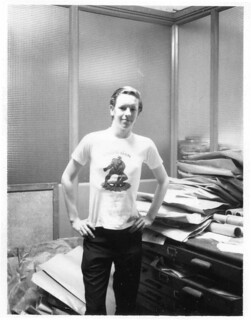

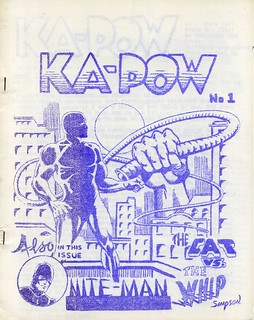

And then six months later, out of the blue, I got a letter from a lady at Odhams Press, saying they had a vacancy for an office junior. At the time, they were publishing their ‘Power Comics’ line, which revolved round reprinting Marvel strips in black-and-white, which was right up my street. I went for an interview and was told I was a bit too old, being nearly 18, but I was enthusiastic, knowledgeable about American comics, and I could show them Ka-Pow. So they offered me the job. Everyone at Rank’s told me I was making a really bad mistake, giving up a job with ‘prospects’ to be an office boy, and for less money too … but I was off as soon as my week’s notice had run out.

I started at Odhams, in their offices at 64 Long Acre, on 1st May 1967. The date sticks in my mind because the first thing they did was send me over to Blackfriars to join the NATSOPA trade union and, of course, being Mayday, the offices were shut. Perhaps not the best of omens to start my career with …

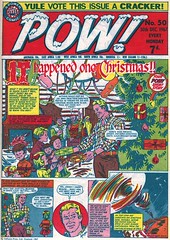

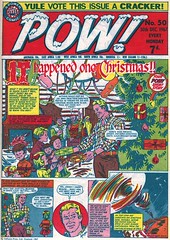

Having arrived, I found that I was actually the junior office junior, there being another guy who’d already been there a year or two. My duties were pretty much getting post in and out of the building, running errands, and so on, but I adopted a simple strategy: when I didn’t actually have any specific tasks, I’d head for the offices of the various different comics and asked the editors if there was anything they needed me to do for them. So within three months I’d leapfrogged the other guy (who I don’t think ever did get beyond being office junior) and got myself promoted to junior sub-editor on Pow! and Fantastic. Both of these were run from the same office, under the editorship of long-time professional scriptwriter Ken Mennell who, I see from looking on the web, sadly seems to be far more honoured in France than in the land of his birth … probably as a result there being no credits for writers and artists in those days. We were a team of four: Ken, who was also contracted to write a couple of adventure scripts a week as part of his duties, a senior sub-editor called Jane, another sub-editor called Paul, and myself. And I was working in professional comics …

PÓM: What did all those sub-editors actually do, or was that just a catch-all title for anyone who worked on a given title?

SM: Well, we were producing two titles a week, Pow! and Fantastic, so everything was on a pretty tight schedule. Ken Mennell was in overall charge and made the ‘strategic’ decisions, like which strips we’d run, in collaboration with managing editor Alf Wallace. I think Jane was mainly responsible for Fantastic, which, being mostly page-for-page reprints of Marvel Comics in black-and-white, with only one original strip (‘The Missing Link’, which later evolved into ‘Johnny Future’; written by Alf Wallace and drawn by Luis Bermejo), was a relatively simple, one-person job. Paul and I worked on Pow! which was a bit more complicated, being more a of traditional British comic apart from the ‘Spider-man’ reprint, which had to be resized to fit a British page format. It was mostly one or two page humour strips, with one or two original adventure strips, so that meant a lot to keep track of. We had a large-format ‘make-up book’, with two pages per issue and a sort of grid system on them, in which we’d write the dates that scripts arrived; when they were sent to the artist; when the artwork came back; when the pages were sent to the letterer (all hand-lettering in those days; no computer setting) and when they came back; and so on. Scripts had to be read and edited before they were sent out, and when the finished, lettered pages were in they had to be proofread and sent to the art department (the ‘bodgers’) for correction. I think we all proofread the pages to make sure nothing got through that shouldn’t be there, as the letterers were known to be occasionally mischievous … particularly John Aldrich, who seemed to take every possible opportunity to letter ‘public’ as ‘pubic’, and so on, just to see what he could get through … and Ken, as editor, certainly checked all the pages after we juniors had been through them. It was also drummed into us that we should never allow the use of the word ‘flick’ or the name ‘Clint’, which, when lettered in capitals were dangerously liable to turn into something quite unsuitable for a kid’s comic. Another maxim I learned very early on was ‘all printers are bloody idiots’, which meant their instructions had to be spelled out absolutely precisely, especially when it came to things like marking up the artwork with its reproduction size. Again, all this was pre-computers, so we were sending original artwork to the printer, and all the corrections had to be done by hand, rather than on screen. Obviously we also got proofs back from the printers that had to be checked through as well. ‘Editorial’ largely consists of reading stuff over and over again.

SM: Well, we were producing two titles a week, Pow! and Fantastic, so everything was on a pretty tight schedule. Ken Mennell was in overall charge and made the ‘strategic’ decisions, like which strips we’d run, in collaboration with managing editor Alf Wallace. I think Jane was mainly responsible for Fantastic, which, being mostly page-for-page reprints of Marvel Comics in black-and-white, with only one original strip (‘The Missing Link’, which later evolved into ‘Johnny Future’; written by Alf Wallace and drawn by Luis Bermejo), was a relatively simple, one-person job. Paul and I worked on Pow! which was a bit more complicated, being more a of traditional British comic apart from the ‘Spider-man’ reprint, which had to be resized to fit a British page format. It was mostly one or two page humour strips, with one or two original adventure strips, so that meant a lot to keep track of. We had a large-format ‘make-up book’, with two pages per issue and a sort of grid system on them, in which we’d write the dates that scripts arrived; when they were sent to the artist; when the artwork came back; when the pages were sent to the letterer (all hand-lettering in those days; no computer setting) and when they came back; and so on. Scripts had to be read and edited before they were sent out, and when the finished, lettered pages were in they had to be proofread and sent to the art department (the ‘bodgers’) for correction. I think we all proofread the pages to make sure nothing got through that shouldn’t be there, as the letterers were known to be occasionally mischievous … particularly John Aldrich, who seemed to take every possible opportunity to letter ‘public’ as ‘pubic’, and so on, just to see what he could get through … and Ken, as editor, certainly checked all the pages after we juniors had been through them. It was also drummed into us that we should never allow the use of the word ‘flick’ or the name ‘Clint’, which, when lettered in capitals were dangerously liable to turn into something quite unsuitable for a kid’s comic. Another maxim I learned very early on was ‘all printers are bloody idiots’, which meant their instructions had to be spelled out absolutely precisely, especially when it came to things like marking up the artwork with its reproduction size. Again, all this was pre-computers, so we were sending original artwork to the printer, and all the corrections had to be done by hand, rather than on screen. Obviously we also got proofs back from the printers that had to be checked through as well. ‘Editorial’ largely consists of reading stuff over and over again.

So, all that had to be controlled, and artists and writers phoned up and chased to make sure everything was on schedule. Then there was the mail to go through (perhaps a hundred letters and postcards a week, most of which was unusable) and pick out possible items for the letters page, and we’d ask the kids who wrote in to include a coupon on which they named their three favourite strips; so these had to be added up to give us an idea what was most popular. And at the same time we were working on a new project, a much more traditional adventure comic in the Lion mould called Spitfire, which had no Marvel reprints; but that never got beyond the dummy stage, as by then the Power Comics line was starting to contract. So we had plenty to keep us occupied, though we always left the office on time; I don’t remember us ever being pressurised into actually doing any overtime.

That was also when I got my first freelance work, though it wasn’t writing. As the Spider-man material we were reprinting in black-and-white was merely the line-work for something had originally been drawn for colour, we used to give it a bit more body by applying Zipatone (an adhesive film that had to be imported from the States at the time, which was then laid on the artwork and cut to shape with a scalpel) to various parts of the pictures. I managed to persuade the art editor, John Jackson, that I could do that, and did so for a number of months. It paid a massive 5/- a page, but to put that in perspective, my weekly salary was only something like £15.

PÓM: What was the Power Comics line, which you mentioned above?

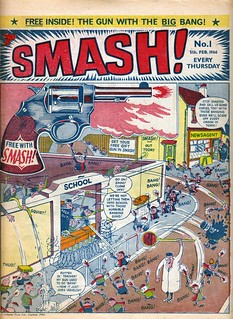

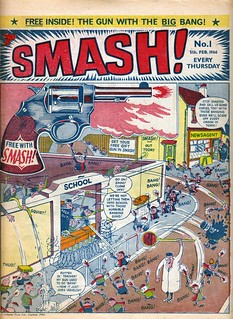

SM: Basically it was Odhams’ attempt to model itself on Marvel Comics and included a fair amount of Marvel reprint. The titles involved were Wham! and Smash! , which were already established as more traditional British comics, but then started to include one or two Marvel reprints, with the American material

SM: Basically it was Odhams’ attempt to model itself on Marvel Comics and included a fair amount of Marvel reprint. The titles involved were Wham! and Smash! , which were already established as more traditional British comics, but then started to include one or two Marvel reprints, with the American material

resized to fit a British page;

Pow! which was in the same format, but was first published at the beginning of the Power Comics line, and

Fantastic and

Terrific, which were in a more American format, each page reproducing a single American page, though each carried one original, British-created strip. There were letters pages, and all the comics carried a half-page news section, in imitation of Marvel’s ‘

Bullpen Bulletins’, ‘

From the Floor of 64’, which was named after 64 Long Acre, the office address; while instead of ‘Smilin’ Stan’ Lee, we had ‘Alf, Bart and Cos’: Alf Wallace, the managing editor, Robert Bartholomew, his No. 2 and editor of

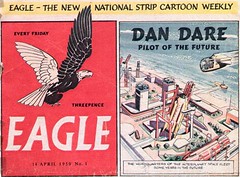

Eagle, and Albert Cosser, editor of

Smash! and

Terrific (who later went on to edit

TV Times for several years). I’m not sure why Ken Mennell wasn’t included in that lot, but maybe they couldn’t fit him in with the ‘A, B, C’ of the other three.

As I said, the offices were at 64 Long Acre, an old newspaper building on the edge of Covent Garden. The ground floor was full of loading bays and was still in use for storing enormous rolls of newsprint, etc. We occupied the entire first floor, which was divided up into smaller offices with metal and frosted glass partition walls. The place was actually a listed building, but it stood on a very prime piece of real estate. A few months after we moved out of the building, it burned to the ground, thus allowing a large and costly redevelopment to take place. Curious, that …

PÓM: What other comics were Odhams producing at the time?

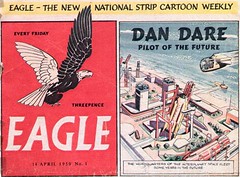

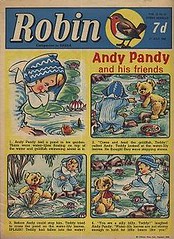

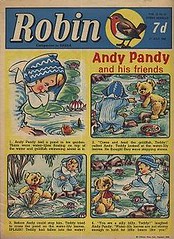

SM: Eagle and Robin, which Odhams had taken over from their original publisher, Hulton Press, in 1959. Their companion papers, Swift and Girl had already folded by then. Eventually all the Power Comics titles started to suffer from declining sales, and merged with each other until there was only Smash! left. Then in 1969 Odhams and Fleetway were merged to become IPC Magazines, and that was pretty much the end of the line. For the last few months of Odhams’ independent existence we moved from Long Acre to offices in High Holborn, and then with the merger everything was transferred to Fleetway House in Farringdon Street.

SM: Eagle and Robin, which Odhams had taken over from their original publisher, Hulton Press, in 1959. Their companion papers, Swift and Girl had already folded by then. Eventually all the Power Comics titles started to suffer from declining sales, and merged with each other until there was only Smash! left. Then in 1969 Odhams and Fleetway were merged to become IPC Magazines, and that was pretty much the end of the line. For the last few months of Odhams’ independent existence we moved from Long Acre to offices in High Holborn, and then with the merger everything was transferred to Fleetway House in Farringdon Street.

PÓM: What was the British comics industry like at the time?

SM: It was in pretty good health, which was probably about the last time you could say that. There were Odhams and Fleetway in London, and D. C. Thomson in Dundee, all with a sizeable number of titles, and a few smaller publishers. Of course, Odhams (and IPC after 1969) was the only one I had direct experience of, and that was also the first one that really had any awareness that there might actually be ‘fans’ to be catered to, rather than just kids who bought the comics off the newsstands. But all the creators were anonymous, this being long before anyone got credits, so there was far less egotism than there is in present-day comics. I tend to look back on it as ‘days of honest toil’, when you had a bunch of solid, professional writers and artists who’d turn in their material on time and take their pay-cheques without ever thinking they were doing anything particularly interesting, because they were working for children’s magazines, and that was how they made their living. I think I was pretty much the first fan to get into the business, and after that there were a few others, but in 1967 things were pretty much a closed shop, often with people introducing friends or members of their own family to the editorial staff. Ken Mennell’s son Ian ended up on editorial at IPC, while the writer Ted Cowan’s son Geoff was on the editorial staff of Eagle. At the time no one thought there was anything ‘special’ about comics, and I think a number of the editorial staff just considered it a relatively easy way to get their press cards from the National Union of Journalists, which they could then use as a stepping stone to move on to a better job as a magazine journalist.

PÓM: Did you sell any of your stories at that time?

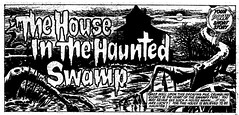

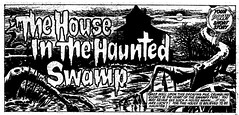

SM: The first story I sold professionally was a three-page ‘Pow Short Story’ called ‘The House in the Haunted Swamp’, that appeared in Pow! No. 45, late in 1967. It was drawn by a Turkish artist living in this country, called Ayhan Basuglu, and taught me a swift lesson, similar to the one about all printers being idiots … which was that you had to write for artists as if they were idiots as well, especially if English wasn’t their first language. It was set in a decaying house full of barrels of paraffin, and I’d told the artist to draw a guy exploring the place with a torch in his hand … meaning, of course, an electric flashlight. Mr. Basuglu promptly drew him with flaming torch, which wasn’t quite what I’d intended with all that paraffin around, so I had to do a bit of rewriting on the dialogue. By one of those weird symmetries, the same sort of thing happened on the last comic strip I wrote as well, Hercules: The Knives of Kush. On one issue they brought in a couple of Mexican artists to fill in, as Cris Bolson was getting behind schedule. My script asked for some characters wearing skullcaps, by which I meant close-fitting felt caps covering the cranium, and they drew a bunch of guys with actual skulls on their heads. Fortunately we managed to catch that at the pencil stage, so it wasn’t a problem, but with 40 years between the two events, you understand my feeling of déjà vu …

SM: The first story I sold professionally was a three-page ‘Pow Short Story’ called ‘The House in the Haunted Swamp’, that appeared in Pow! No. 45, late in 1967. It was drawn by a Turkish artist living in this country, called Ayhan Basuglu, and taught me a swift lesson, similar to the one about all printers being idiots … which was that you had to write for artists as if they were idiots as well, especially if English wasn’t their first language. It was set in a decaying house full of barrels of paraffin, and I’d told the artist to draw a guy exploring the place with a torch in his hand … meaning, of course, an electric flashlight. Mr. Basuglu promptly drew him with flaming torch, which wasn’t quite what I’d intended with all that paraffin around, so I had to do a bit of rewriting on the dialogue. By one of those weird symmetries, the same sort of thing happened on the last comic strip I wrote as well, Hercules: The Knives of Kush. On one issue they brought in a couple of Mexican artists to fill in, as Cris Bolson was getting behind schedule. My script asked for some characters wearing skullcaps, by which I meant close-fitting felt caps covering the cranium, and they drew a bunch of guys with actual skulls on their heads. Fortunately we managed to catch that at the pencil stage, so it wasn’t a problem, but with 40 years between the two events, you understand my feeling of déjà vu …

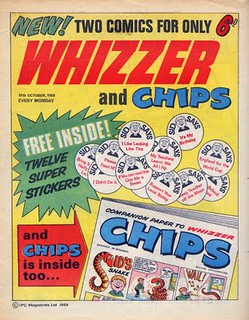

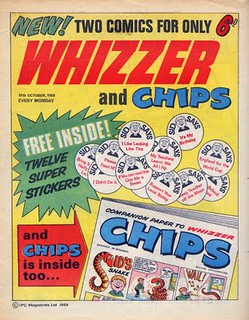

I know I wrote another ‘Pow Short Story’ called ‘The Hunter out of Time’, which, like the first one, suffered from the usual beginner’s error of having far too many words per panel, and there may have been one or two more. Those are the only two I know I wrote, because in those early days I’d keep a scrapbook of the stories I’d done, but after I’d been freelance a few months there got to be so many of them I just gave up. When I was on editorial for Whizzer & Chips at IPC I wrote a four-episode fill-in on ‘Wonder-Car’, which I really enjoyed as it was drawn by Ron Turner, someone I’d long admired. But I didn’t really write a great deal while I was working in-house, and when I went freelance in 1972, it was pretty much a leap in the dark. I thought I could write, but I didn’t actually have any sort of track record that said I could. It was pretty much the way I blundered through my career. ‘You want a prose story written (or a novel, or a movie script, or whatever)? Oh yeah, I can do that …’ I never had any prior experience of doing them, but as it turned out, I could. Looking back, I seem to have got away with an awful lot, somehow. It’s just that I’m not sure how I did it!

PÓM: Do you remember many of the people who worked on the comics?

SM: As for the in-house staff, apart from the people I’ve already mentioned I mostly just remember first names, though the overall art editor was John Jackson, his assistant Roger Barnden. One of the senior sub-editors on Eagle was a guy called Dan Lloyd, who also happened to be the assistant editor on Flying Saucer Review, and when I was still the office boy I’d sometimes have to run UFO stuff between him and the editor, Charles Bowen, who worked at South Africa House in Trafalgar Square. At one point Dan had his new toy set up in the Eagle office, which was next door to ours … a ‘flying saucer detector’, which I think was some sort of magnetometer that FSR was promoting, so Roger Barnden used to sneak into our office and slap a powerful magnet on the metal partition wall, just to wind up Dan by setting off his detector.

As for creators, a lot of the humour strips were written by Walter Thorburn, who we’d lured away from D. C. Thomson, who were notorious for paying less than their London-based competitors. They’d also lured away Leo Baxendale, though I think he worked mainly for Wham! As for the adventure strips, I think Ken Mennell wrote mainly for Smash! … I’m fairly sure he wrote ‘Rubber Man’ ‘Bunsen’s Burner’ and ‘Cursitor Doom’ for them. Another string to his bow was coming up with plot outlines for thriller novels for the publisher W. Howard Baker, who had a stable of writers who’d then write them up. Ken would knock out the outlines in his lunch hours, at £30 a time, and I was obviously impressed by his productivity. Other adventure writers were Tom Tully and Scott Goodall, but I can’t remember which strips they were responsible for. As for humour artists, there was Mike Brown, who was very much a Leo Baxendale clone, and who I suspect may well be the artist on some material that’s been mistakenly identified as Baxendale. There was Mike Higgs, writing and drawing ‘The Cloak’, and the brilliant Ken Reid on ‘Dare-a-Day Davy’, who was actually a bit of a nightmare to work with, as he’d rewrite all the scripts he was sent, and we’d get back this lovely artwork with tiny pencilled dialogue in the balloons that was twice as long as would actually fit if lettered properly, so we had to cut it in half to make it work. There was Graham Allen and Terry Bave, who also wrote his own stuff. As for adventure artists, there were John Stokes and Eric Bradbury, though a fair number of stories were by Spanish artists, working through agencies like the Temple Art Agency.

As for creators, a lot of the humour strips were written by Walter Thorburn, who we’d lured away from D. C. Thomson, who were notorious for paying less than their London-based competitors. They’d also lured away Leo Baxendale, though I think he worked mainly for Wham! As for the adventure strips, I think Ken Mennell wrote mainly for Smash! … I’m fairly sure he wrote ‘Rubber Man’ ‘Bunsen’s Burner’ and ‘Cursitor Doom’ for them. Another string to his bow was coming up with plot outlines for thriller novels for the publisher W. Howard Baker, who had a stable of writers who’d then write them up. Ken would knock out the outlines in his lunch hours, at £30 a time, and I was obviously impressed by his productivity. Other adventure writers were Tom Tully and Scott Goodall, but I can’t remember which strips they were responsible for. As for humour artists, there was Mike Brown, who was very much a Leo Baxendale clone, and who I suspect may well be the artist on some material that’s been mistakenly identified as Baxendale. There was Mike Higgs, writing and drawing ‘The Cloak’, and the brilliant Ken Reid on ‘Dare-a-Day Davy’, who was actually a bit of a nightmare to work with, as he’d rewrite all the scripts he was sent, and we’d get back this lovely artwork with tiny pencilled dialogue in the balloons that was twice as long as would actually fit if lettered properly, so we had to cut it in half to make it work. There was Graham Allen and Terry Bave, who also wrote his own stuff. As for adventure artists, there were John Stokes and Eric Bradbury, though a fair number of stories were by Spanish artists, working through agencies like the Temple Art Agency.

It was while working on Pow! and Fantastic in 1967 that I first met Steve Parkhouse and Barry Smith (this was before he moved to the States and started calling himself Barry Windsor-Smith). They turned up one day as a writer-artist team, trying to sell us an SF strip as a ‘Pow Short Story’. It wasn’t accepted, but Barry ended up drawing the pin-ups of Marvel characters on the back cover of Fantastic and Terrific. I’m not exactly sure when he started, but the early pin-ups were drawn in-house by John Jackson.

PÓM: Did you end up working with any of your professional colleagues on any of your fan publications?

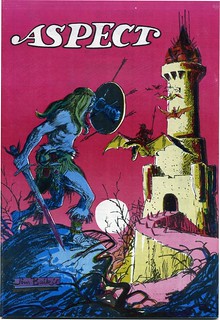

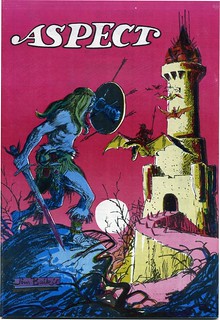

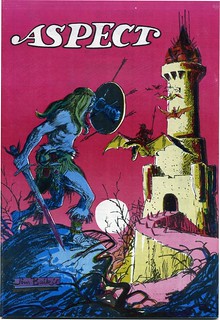

SM: Eventually, yes. I’d started another fanzine called Aspect, the first issue of which appeared in September 1969. It was the first comics fanzine I’d done using a Gestetner duplicator, and was run off for me by Derek Stokes, but I wasn’t at all pleased with it; in fact I was rather embarrassed at the way it came out. But by the time I got round to doing the second issue, in March 1970, I’d got in touch with the guys at Orion Press in Manchester, who were essentially fan printers, but who could do justified typesetting and litho printing, including fairly primitive overlay colour covers. Steve and Barry had been working on a large Kirby-esque epic called ‘Paradox Man’ which I was quite eager to run, but instead Barry decided to intercut pages from that with a number of apparently unrelated other pages and the whole thing ended up as a sort of 20-page montage called ‘Tales of Hyperborea’, which looked very nice, so long as you didn’t expect any sort of connected narrative. There was a prose sword-and-sorcery by Chris Lowder, who I was by now working with at IPC, and who later started calling himself Jack Adrian, with a career as a writer, anthologist and critic; that was illustrated by Steve Parkhouse. And there was an article on Frankenstein movies by Denis Gifford.

SM: Eventually, yes. I’d started another fanzine called Aspect, the first issue of which appeared in September 1969. It was the first comics fanzine I’d done using a Gestetner duplicator, and was run off for me by Derek Stokes, but I wasn’t at all pleased with it; in fact I was rather embarrassed at the way it came out. But by the time I got round to doing the second issue, in March 1970, I’d got in touch with the guys at Orion Press in Manchester, who were essentially fan printers, but who could do justified typesetting and litho printing, including fairly primitive overlay colour covers. Steve and Barry had been working on a large Kirby-esque epic called ‘Paradox Man’ which I was quite eager to run, but instead Barry decided to intercut pages from that with a number of apparently unrelated other pages and the whole thing ended up as a sort of 20-page montage called ‘Tales of Hyperborea’, which looked very nice, so long as you didn’t expect any sort of connected narrative. There was a prose sword-and-sorcery by Chris Lowder, who I was by now working with at IPC, and who later started calling himself Jack Adrian, with a career as a writer, anthologist and critic; that was illustrated by Steve Parkhouse. And there was an article on Frankenstein movies by Denis Gifford.

For some time, Steve and Barry had been intending to do a magazine called Orpheus, along with Bob Rickard, who they’d actually got in touch with after seeing a letter that Bob had had published in a Marvel Comic. So at that point we decided to merge and brought out the first issue of Orpheus in March 1971, nominally edited by Steve and myself, though we all had an input into the issue. By that time Steve was working at IPC with me on Whizzer and Chips and Cor!! So we roped in a few of our friends from there as well, like Chris Lowder and Robert Knight, and again we had strips by Steve and Barry. We actually managed to get a second issue together and printed by Spring 1973, which featured some very early art by Ian Gibson, but Steve and Barry then decided they weren’t satisfied with it, so it was never released, though I managed to nab one copy for my own files.

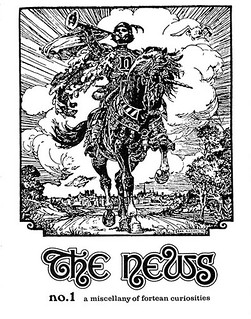

Eventually Barry moved to the States and Steve to Carlisle, and, sadly, we lost touch. But Bob’s remained one of my very dearest friends for the last 45 years and, of course, it’s because of that that I’ve had a long-running association with Fortean Times since it began in 1973.

PÓM: Were they good times or bad times at Odhams, do you think, looking back?

SM: Certainly good when I was working on Pow! Ken Mennell was a nice man, London was a hip place to work in 1967 and I was doing what I wanted to do, which was working in comics. As things started to shrink Ken left and I ended up working on Smash! , which wasn’t quite so much fun, simply because I didn’t take to Albert Cosser (who was always called ‘Cos’ rather than Albert) quite as much as I did to Ken, though we got on well enough. By 1969 the writing was on the wall, and we knew about the upcoming merger with Fleetway, and for the last few months we moved from Long Acre to offices in High Holborn. For the last month of its life I worked as extra editorial staff on Eagle, which was quite nice, as I’d grown up with the title, but it was pretty much just a case of giving me something to do. Except for a couple of people, virtually everyone at Odhams took redundancy pay, but I’d only been there a couple of years, so that wasn’t worth anything to me and, besides, I wanted to stay in comics. So I hung on and moved over to Fleetway House as part of the new IPC Magazines set-up where, at least to start with, I wasn’t anywhere near as happy.

PÓM: Why not?

SM: Well, I’d basically gone over to Fleetway House as ‘superfluous editorial staff’, and they promptly put me on Valiant, which already had a full staff so I was, basically, superfluous. And while Odhams had been quite relaxed, the whole ethos at Fleetway was much more old-fashioned, with very rigid and strait-laced working practices. The managing editor was a guy called Jack LeGrand, who looked like a rather beaten-up old newspaper hack. He was probably perfectly nice, but I seem to recall there’d be a vague tremor every time he’d walk into an office. The editor of Valiant, Sid Bicknell, was a complete martinet, and I think his chief sub-editor, who was probably only about 30, used to turn up every day in a three-piece suit and a bow-tie. So I got dumped among a staff like that with my lengthening hair and vaguely hippy notions, and we spent six months in mutual loathing.

Valiant was probably the most old-fashioned of the Fleetway boys’ adventure weeklies, and I particularly detested their lead strip, the ‘jolly’ World War II hero Captain Hurricane, which I thought was nauseatingly jingoistic and downright racist (‘Take that, you piano-toothed rice-noshing baboons!’). I seem to remember working for a couple of weeks on Tiger at the end of my stint on Valiant, but then, without asking me what I thought, they suddenly decided to move me on to War Picture Library, which, of course, I hated even more. For those who don’t remember them, these were pocket sized-comics about seven inches by five, with 56 pages plus covers, and usually two or three panels a page.

Working on War Picture Library was even more dire than Valiant. I remember early on having proofread an issue in 25 minutes, and then being told that I couldn’t have read it properly because all the other staff there took 45 minutes. So after that I had to spend 45 minutes on a book regardless of whether it needed it, and some of the stuff was reprint that had already been subbed anyway. I was bored rigid and hated the subject matter, with its constant references to ‘Huns’ and ‘Nips’, and the typical World War II story is something I’ve always refused to write. Mind you, I’ve never written sport either, but that’s mainly because of ignorance rather than any moral scruples.

PÓM: Did you end up working at IPC Magazines for long?

SM: Fortunately, after two months of misery on the War libraries, they decided to bring out a new humour weekly called Whizzer and Chips, under a relatively young editor called Bob Paynter; the idea being that Chips was somehow a ‘separate’ comic that was bound inside Whizzer. As was usually the way, they advertised the job of sub-editor in-house first, and I naturally applied for it, and got it. So that’s where I spent the next two years, until I finally left to go freelance in the summer of 1972. During that time, we also added Cor!! to our line-up, which was another humour title. Both were pretty much modelled on Buster, but perhaps with a slightly younger appeal. They were virtually all humour (a lot of which was written by Roger Cook, who’d formally written TV Comic just about single-handedly every week) with, I think, one adventure strip.

SM: Fortunately, after two months of misery on the War libraries, they decided to bring out a new humour weekly called Whizzer and Chips, under a relatively young editor called Bob Paynter; the idea being that Chips was somehow a ‘separate’ comic that was bound inside Whizzer. As was usually the way, they advertised the job of sub-editor in-house first, and I naturally applied for it, and got it. So that’s where I spent the next two years, until I finally left to go freelance in the summer of 1972. During that time, we also added Cor!! to our line-up, which was another humour title. Both were pretty much modelled on Buster, but perhaps with a slightly younger appeal. They were virtually all humour (a lot of which was written by Roger Cook, who’d formally written TV Comic just about single-handedly every week) with, I think, one adventure strip.

We were down on the second floor (most of the comics were on the top floor, which I can’t remember whether it was the 5th or the 6th, with the libraries on the floor below that), so we were pretty much a separate production unit, cut off from the others (which suited me). And in the time I was there, we ended up with Steve Parkhouse and Dez Skinn on editorial (I think Dez was mainly on Cor!! ), and Kevin O’Neill as art assistant. With the usual nepotistic way of taking on staff, we also had an art assistant called Tony Jacob, who was the son of a cartoonist, I think called Peter Jacob, and there was a rather cute artist/letterer called Diane Flowers, who was developing an interest in palmistry and wanted to read my palm (offhand I can’t remember what she said, just the inky palm-prints … though I think it was more about character analysis than prediction). I don’t think Chris Lowder worked with us, but I think he hung around quite a lot, mainly because of the aforesaid palmist. So we had a decent team there, and Steve Parkhouse and I became quite good friends. And I was reasonably happy for a while.

To be continued…

|

| © 2009 Mari Kurisato |

We knew this day was coming, but that doesn't really make it easier.

After years of struggling with cancer,

Jay Lake has died.

Jay leaves a legacy of family, of friendships, of writing, and of science. He had his genome sequenced, and he submitted himself to grueling experimental trials. He could have gone more quietly into this good night; he chose instead to try to help the people of a future that has been denied to him. One of his greatest legacies may be to have helped, in some small or large way, to move us closer to a cure for cancer.

In place of eulogy,

here's something I wrote when Jay could read it.

Farewell, friend.

We were saddened to hear of the passing of Maya Angelou. Here are some books by which to help remember the great author and poet.

Adoff, Arnold and Andrews, Benny, Editors I Am the Darker Brother: An Anthology of Modern Poems by African Americans

Adoff, Arnold and Andrews, Benny, Editors I Am the Darker Brother: An Anthology of Modern Poems by African Americans

208 pp. Simon 1997. ISBN 0-689-81241-8 PE ISBN 0-689-80869-0

YA (New ed., 1968, Macmillan). Introductory comments by poet Nikki Giovanni and literary critic Rudine Sims Bishop reinforce the continued timeliness of this volume, updated and reissued after nearly thirty years. Expanded with pieces from twenty-one additional poets including Maya Angelou and poet laureate Rita Dove, the collection constitutes a part of the song of America, which, as Bishop states, ‘requires a multi-voiced chorus.’ Ind.

Angelou, Maya Amazing Peace: A Christmas Poem

Angelou, Maya Amazing Peace: A Christmas Poem

40 pp. Random/Schwartz & Wade 2008. ISBN 978-0-375-84150-7 LE ISBN 978-0-375-94327-0

Gr. K-3 Illustrated by Steve Johnson and Lou Fancher. Angelou’s poem (first read at the 2005 White House tree-lighting ceremony) is about the promise of peace brought on by the Christmas season, urging listeners to “look beyond complexion and see community.” The luminous oil, acrylic, and fabric illustrations on canvas, depicting a snow-covered town, add concreteness to Angelou’s words. A CD of Angelou reading the poem is included.

Angelou, Maya My Painted House, My Friendly Chicken, and Me

Angelou, Maya My Painted House, My Friendly Chicken, and Me

40 pp. C. Potter 1994. ISBN 0-517-59667-9

Gr. K-3 Photographs by Margaret Courtney-Clarke. Thandi, an eight-year-old Ndebele girl of South Africa, tells about her family, the fine art of house painting carried out mainly by the women in the village, and the contrast between village and city life. Courtney-Clarke’s abundant, brightly colored photographs accompany Angelou’s refreshingly warm introduction to the art, culture, and social life of the Ndebele people.

Clinton, Catherine, Editor I, Too, Sing America: Three Centuries of African American Poetry

Clinton, Catherine, Editor I, Too, Sing America: Three Centuries of African American Poetry

128 pp. Houghton 1998. ISBN 0-395-89599-5

YA Illustrated by Stephen Alcorn. This chronological collection includes work by such poets as Phillis Wheatley, W. E. B. Du Bois, Arna Bontemps, Maya Angelou, Rita Dove, along with twenty others. The verses, introduced with biographical information, reflect the African-American struggle for equality from the early 1800s to the present. The textured illustrations, done in muted tones, capture the drama and strength of each poem.

Cox, Vicki Maya Angelou: Poet

Cox, Vicki Maya Angelou: Poet

122 pp. Chelsea 2006. LE ISBN 0-7910-9224-0

YA Black Americans of Achievement, Legacy Edition series. (New ed., 1994.) This biography details Angelou’s rise from adversity to international recognition. The book goes beyond the typical personal information to provide some social history relevant to the subject’s time. Captioned photographs and boxed inserts enhance the conversational text, most of which has been completely revised. Reading list, timeline, websites. Ind.

Johnson, Claudia, Editor Racism in Maya Angelou’s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings

Johnson, Claudia, Editor Racism in Maya Angelou’s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings

150 pp. Greenhaven 2008. LE ISBN 978-0-7377-3901-5

YA Social Issues in Literature series. This volume presents brief, thoughtful essay reprints (primarily written by literary critics and academics) arranged into three sections that explore the author’s life, identify relevant social issues, and discuss current cultural applications. Although the pieces are sometimes awkwardly truncated, they usually present ideas that go well beyond superficial critique, inviting readers to consider fiction as a vehicle for analyzing American identity. Reading list, timeline, Bib., ind.

Rampersad, Arnold and Blount, Marcellus, Editors African American Poetry: Poetry for Young People

Rampersad, Arnold and Blount, Marcellus, Editors African American Poetry: Poetry for Young People

48 pp. Sterling 2013. ISBN 978-1-4027-1689-8

Gr. 4-6 Illustrated by Karen Barbour. This representative poetry anthology of African American literary masters spans the sixteenth through twentieth centuries and includes renowned poets such as Phillis Wheatley, Lucille Clifton, Maya Angelou, Langston Hughes, and Nikki Giovanni; brief contextual notes accompany each poem. The selections, along with the watercolor, ink, and collage illustrations, reflect not only the black experience but also the evolution of free expression. Ind.

Wilson, Edwin Graves, Editor Maya Angelou

Wilson, Edwin Graves, Editor Maya Angelou

48 pp. Sterling 2007. ISBN 978-1-4027-2023-9

Gr. 4-6 Illustrated by Jerome Lagarrigue. Poetry for Young People series. After a four-page introduction about Angelou’s life and work, twenty-five of her poems are presented, each with a few explanatory sentences preceding them. Some selections are heavy, resonating with the penetrating philosophical stance from which Angelou views the world; others show a lighter side of the world-renowned wordsmith. Dark abstract paintings create mood and atmosphere. Ind.

The post Books in Remembrance of Maya Angelou (1928-2014) appeared first on The Horn Book.

Famed writer Maya Angelou has passed away. She was 86-years-old.

Here's more from The New York Times: "Throughout her writing, Ms. Angelou explored the concepts of personal identity and resilience through the multifaceted lens of race, sex, family, community and the collective past. As a whole, her work offered a clear-eyed examination of the ways in which the socially marginalizing forces of racism and sexism played out at the level of the individual."

In addition to writing, Angelou proved to be an accomplished Renaissance woman who worked as an activist, entertainer, streetcar conductor, magazine editor, college professor, and lecturer. To commemorate Angelou's life in letters, we have put together a literary mix tape. Below we've included links to free excerpts of Angelou’s books and poems. (Photo Credit: Dwight Carter)

continued...

New Career Opportunities Daily: The best jobs in media.

Via a series of Tweets from

Tamara K. Nopper, I learned that

William Worthy recently died at the age of 92.

I knew very little about Worthy the man, but his name has been one I've known since childhood, because of a

Phil Ochs song about him,

"The Ballad of William Worthy".

My father was a DJ at a radio station in Massachusetts in the 1960s and played that song one day, because though his politics were rather different from those of Ochs or Worthy (he voted for Nixon and generally supported the Vietnam War), he loved to challenge authority and get in trouble. That he did. As he told it, a bunch of little old ladies wrote letters to the station to demand that this upstart DJ be fired. The station manager screamed at him never to play anything like that damned song ever again.

By the time I was old enough to be taught the contents of the record collection at home, I heard that story and listened to the song. It was a catchy tune, and because I associated it with my father's amusing rebellion, I took a particular liking to it and quickly learned the words. And thus I have carried William Worthy's name with me ever since.

William Worthy isn't worthy to enter our door

Went down to Cuba, he's not American anymore

But somehow it is strange to hear the State Department say

You are living in the free world, in the free world you must stay

But Worthy was much more than just a journalist who went to Cuba. His is a story worth learning, a name worth remembering.

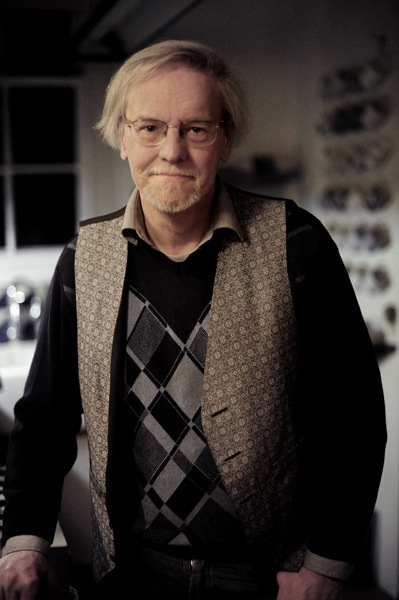

On the 26th of August 2013 I started doing a very long biographical interview with Steve Moore (as mentioned in my earlier post, Steve Moore 1949 – 2014: A Personal Appreciation). The plan was that it would take as long as it would take, and then we’d spend a bit more time fiddling about with it, then decide exactly what we wanted to do with it. Steve died on the 14th of March, give or take a day. At that point, we had reached the end of the questions and answers about his time at Warrior in the early-mid eighties, and I had sent off three final questions about it, just to clarify a few final details, before we moved on to whatever came next. The answers to those questions, although they were written, never got sent, and were found on Steve’s computer after he died. They’ll eventually make their way to me, and will be in the last post in this series.

On the 26th of August 2013 I started doing a very long biographical interview with Steve Moore (as mentioned in my earlier post, Steve Moore 1949 – 2014: A Personal Appreciation). The plan was that it would take as long as it would take, and then we’d spend a bit more time fiddling about with it, then decide exactly what we wanted to do with it. Steve died on the 14th of March, give or take a day. At that point, we had reached the end of the questions and answers about his time at Warrior in the early-mid eighties, and I had sent off three final questions about it, just to clarify a few final details, before we moved on to whatever came next. The answers to those questions, although they were written, never got sent, and were found on Steve’s computer after he died. They’ll eventually make their way to me, and will be in the last post in this series.

In the meantime, there’s 48,000-ish word of interview between us that I have decided needs to be seen, even though it is unfinished. The current plan is to put it up here in reasonably sizeable chunks, every Sunday.

One note on the text: As we went along, I would ask supplementary questions, which got inserted into the previous text. To make it clear where a question has been added in later, I’ve included little arrows for those subsidiary questions, like this: ->. Occasionally, there were further questions, which are indicated by an ever expanding length of arrow, like this –> or this —>. Hopefully this will help to understand how the interview unfolded. So…

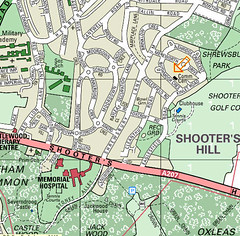

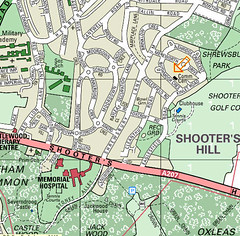

Pádraig Ó Méalóid: Before I get to your own life, can I ask you about your parents? Where they were from, what they did, and how they ended up in the house on Shooters Hill where you were born?

Pádraig Ó Méalóid: Before I get to your own life, can I ask you about your parents? Where they were from, what they did, and how they ended up in the house on Shooters Hill where you were born?

Steve Moore: As far as I can tell, my father, Arthur James Moore, was born in Charlton, South-East London, in 1908, the son of a soldier in the Royal Artillery. For reasons that aren’t very clear (possibly because my grandfather died or left the family), he seems to have started working at the age of 11 for a chemicals company called Frederick Boehm, firstly at Silvertown in East London and later at Belvedere in Kent. He stayed with the same company for the whole of his working life, eventually rising to middle management, before dying of a stroke in 1972.

My mother, Winifred Mary Deeks, was born in 1917, and came from New Cross, also in South-East London. I believe she was working as a secretary at Boehm’s when she met my dad, and they married in 1938, after which she became a housewife. She passed away from a stroke in 1985. The Moore side of the family seem to have been pretty much working class: bakers, soldiers and factory workers, and the earliest trace I’ve been able to find is of a Moore who was a farmer in Derbyshire in the 18th century. The Deeks seem to have originated in Suffolk, where my earliest traceable ancestors seem to have been brickmakers. If I have any sort of vague literary connections in my ancestry it seems to be on the Deeks side; grandfather Deeks was a printer, and my Uncle Don was a book distributor who specialised in oriental publications.

My mother, Winifred Mary Deeks, was born in 1917, and came from New Cross, also in South-East London. I believe she was working as a secretary at Boehm’s when she met my dad, and they married in 1938, after which she became a housewife. She passed away from a stroke in 1985. The Moore side of the family seem to have been pretty much working class: bakers, soldiers and factory workers, and the earliest trace I’ve been able to find is of a Moore who was a farmer in Derbyshire in the 18th century. The Deeks seem to have originated in Suffolk, where my earliest traceable ancestors seem to have been brickmakers. If I have any sort of vague literary connections in my ancestry it seems to be on the Deeks side; grandfather Deeks was a printer, and my Uncle Don was a book distributor who specialised in oriental publications.

Jim and Mary, as they preferred to be known, seem to have lived in Charlton to start with, though they eventually bought the house on Shooters Hill in 1942 (Not 1938, as was stated in Alan Moore’s biographical confection about me, Unearthing, though this information only came to light after Alan wrote the piece). By one of those weird twists of fate, when my father was called up in World War II he was disbarred from serving on the front line because he’d worked for Boehm’s, a German-owned company. As a result he ended up in the Home Guard, working on an anti-aircraft rocket battery on Shooters Hill, which at least didn’t give him very far to walk to work.

My brother Christopher was born in 1943, and evacuated a year later, with my mum, to Gloucester, during the V1 and V2 raids. He eventually began working at Boehm’s too, though by then it had been taken over by the Hercules Powder Company. He rose to laboratory supervisor before being made redundant when the company moved, and spent the rest of his career doing bar work and greenkeeping at Shooters Hill Golf Club, at exactly the same location where my dad’s rocket battery had been situated, and on the same golf course where my dad passed away. Chris eventually died of motor neurone disease in 2009.

My brother Christopher was born in 1943, and evacuated a year later, with my mum, to Gloucester, during the V1 and V2 raids. He eventually began working at Boehm’s too, though by then it had been taken over by the Hercules Powder Company. He rose to laboratory supervisor before being made redundant when the company moved, and spent the rest of his career doing bar work and greenkeeping at Shooters Hill Golf Club, at exactly the same location where my dad’s rocket battery had been situated, and on the same golf course where my dad passed away. Chris eventually died of motor neurone disease in 2009.

And then there was me, of course, born in this house on Shooters Hill on the 11th of June 1949 (at 2:00pm BST, in case anyone wants to work out my horoscope and perform evil magic against me!), and I’ve pretty much been here ever since. We Moores don’t move around much…

PÓM: I presume you went to school locally as well, then?

SM: It certainly was local – In 1954 I started attending Christ Church Primary School, halfway up Shooters Hill and about 200 yards from my house. It’s been extended since, but at the time it was absolutely tiny. Only 60 pupils, spread over six years; ten pupils per year. There were only two classrooms. The first two years (‘infants’) in one, the other vaguely divided into two, with two teachers, who each taught two years simultaneously.

Thinking back, I realise that my physical world was really quite small as a kid. Although I was theoretically in London (the border with Kent was only a quarter of a mile away), being on top of a hill rather cuts you off from the surrounding territory, and half the hill was covered in woods besides. There were a couple of ‘corner shops’ on the hill, but that was all. If you wanted to get to a shopping centre or cinema, etc., you had to get a bus; and as no one in the family drove we tended to stay home a lot. I don’t actually recall eating in a restaurant at all as a kid, unless we were on holiday. In the summer holidays my mum would take me off to the museums in central London, but that meant both a bus and a train to get there, and I didn’t really spend much time at all in central London until I started working there, aged 17. I suspect that may be why I still, to this day, dream an awful lot about trains and stations: they were the portals to the exciting world of possibilities that London represented.

On the other hand, living on top of the hill meant that I had enormous horizons – I could see the whole of central and East London – and a very large sky. I think that may have affected my mindset; I may have been pretty much stuck in one place, but both literally and figuratively I could see for miles, and fill up a very large world with my imagination. Which, being fairly solitary, I did. My brother was six years older than me, so he was already at school before I was born and the age gap meant that we never really played together much; it was a bit like being an only child in a two-child family. So I read a lot from quite early on.

On the other hand, living on top of the hill meant that I had enormous horizons – I could see the whole of central and East London – and a very large sky. I think that may have affected my mindset; I may have been pretty much stuck in one place, but both literally and figuratively I could see for miles, and fill up a very large world with my imagination. Which, being fairly solitary, I did. My brother was six years older than me, so he was already at school before I was born and the age gap meant that we never really played together much; it was a bit like being an only child in a two-child family. So I read a lot from quite early on.

->PÓM: What sort of a child were you: quiet, outgoing, or what?

->SM: I’ve really always been introverted rather than extroverted, so I was quiet, shy, occasionally sulky and easily bored. I also found it quite hard to make really close friendships, and as soon as I left primary school I left behind all the friends I’d made there. The same thing happened with grammar school and the job at Rank’s. The really close friendships I’ve tended to make have been based on shared interests, usually creative or scholarly, and they’ve been few and long-lasting. On the other hand, I think with hindsight that I was also a bit hyperactive, though I’m not sure the term had actually been invented then. In my teens and twenties I’d spend more time pacing up and down in my bedroom than sitting down, listening to music, thinking about story ideas, and so on. I suspect that’s reflected in my rather dilettantish shifting of interests over the years.<-

PÓM: And what sort of things were you interested in as a child?

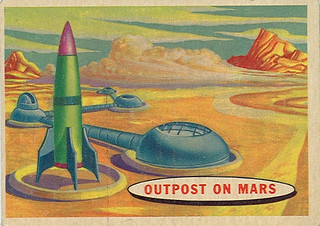

SM: As for early interests, they divided roughly into two. On the one hand, there was the ancient world, and especially mythology – I remember from a very early age having an exercise book in which I’d collect, in my very bad hand-writing (it’s never improved), lists of gods and goddesses from all parts of the world, delighting every time someone gave me a new name to add to my collection.  Possibly that sprang from seeing movies like Helen of Troy or the Steve Reeves Hercules movies (for which I still have a lingering affection), but it’s an interest that’s stayed with me ever since. On the other hand, I was also mad for outer space, especially after the first Sputnik went up in 1957 (about which I still have some original newspaper clippings somewhere in the back of a filing cabinet). Although I read some juvenile SF like E.C. Eliott’s Kemlo series and Angus MacVicar’s Lost Planet books, my interests were mainly non-fictional. I was a member of the junior branch of the Royal Astronomical Society and had my own telescopes; I read Patrick Moore’s books; I collected the complete set of 88 Space Cards bubble-gum cards (published by Topps in the States in 1958, and by ABC here), which explained, speculatively but not fictionally, and with painted images after the style of space artist Chesley Bonestell, how mankind would explore and colonise the solar system (I still have them too – quaint, naïve and absolutely gorgeous).

Possibly that sprang from seeing movies like Helen of Troy or the Steve Reeves Hercules movies (for which I still have a lingering affection), but it’s an interest that’s stayed with me ever since. On the other hand, I was also mad for outer space, especially after the first Sputnik went up in 1957 (about which I still have some original newspaper clippings somewhere in the back of a filing cabinet). Although I read some juvenile SF like E.C. Eliott’s Kemlo series and Angus MacVicar’s Lost Planet books, my interests were mainly non-fictional. I was a member of the junior branch of the Royal Astronomical Society and had my own telescopes; I read Patrick Moore’s books; I collected the complete set of 88 Space Cards bubble-gum cards (published by Topps in the States in 1958, and by ABC here), which explained, speculatively but not fictionally, and with painted images after the style of space artist Chesley Bonestell, how mankind would explore and colonise the solar system (I still have them too – quaint, naïve and absolutely gorgeous).  And, of course, there was Dan Dare to read every week. My brother had taken the Eagle since issue one in 1950, and I just grew into it, and we kept having it delivered every week until it closed in 1969 (those, alas, I don’t have any more). As a kid, I used to think ‘I hope I’m still alive in the 21st century’ (which seemed an awfully long way away then), as I was expecting us to have moon bases, and colonies on Mars, and regular spaceflights. Needless to say, the reality has turned out to be a gross disappointment, to put it mildly.

And, of course, there was Dan Dare to read every week. My brother had taken the Eagle since issue one in 1950, and I just grew into it, and we kept having it delivered every week until it closed in 1969 (those, alas, I don’t have any more). As a kid, I used to think ‘I hope I’m still alive in the 21st century’ (which seemed an awfully long way away then), as I was expecting us to have moon bases, and colonies on Mars, and regular spaceflights. Needless to say, the reality has turned out to be a gross disappointment, to put it mildly.

->PÓM: I’m guessing, from what you’re saying, that you are something of a hoarder?

->SM: Pretty much so. Over the years my comics and SF collections got trimmed back so I pretty much only kept the stuff I really loved at the time, but I find it very difficult to get rid of anything, particularly non-fiction books, which I regard as part of my reference library, and which I also want to pass on to the Fortean Times people when I’m gone, as a research aid. And even though I’ve got the entire house to myself now, it’s still packed to the rafters (literally – the loft’s pretty full too!)<-

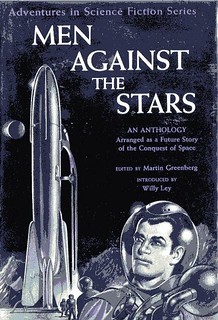

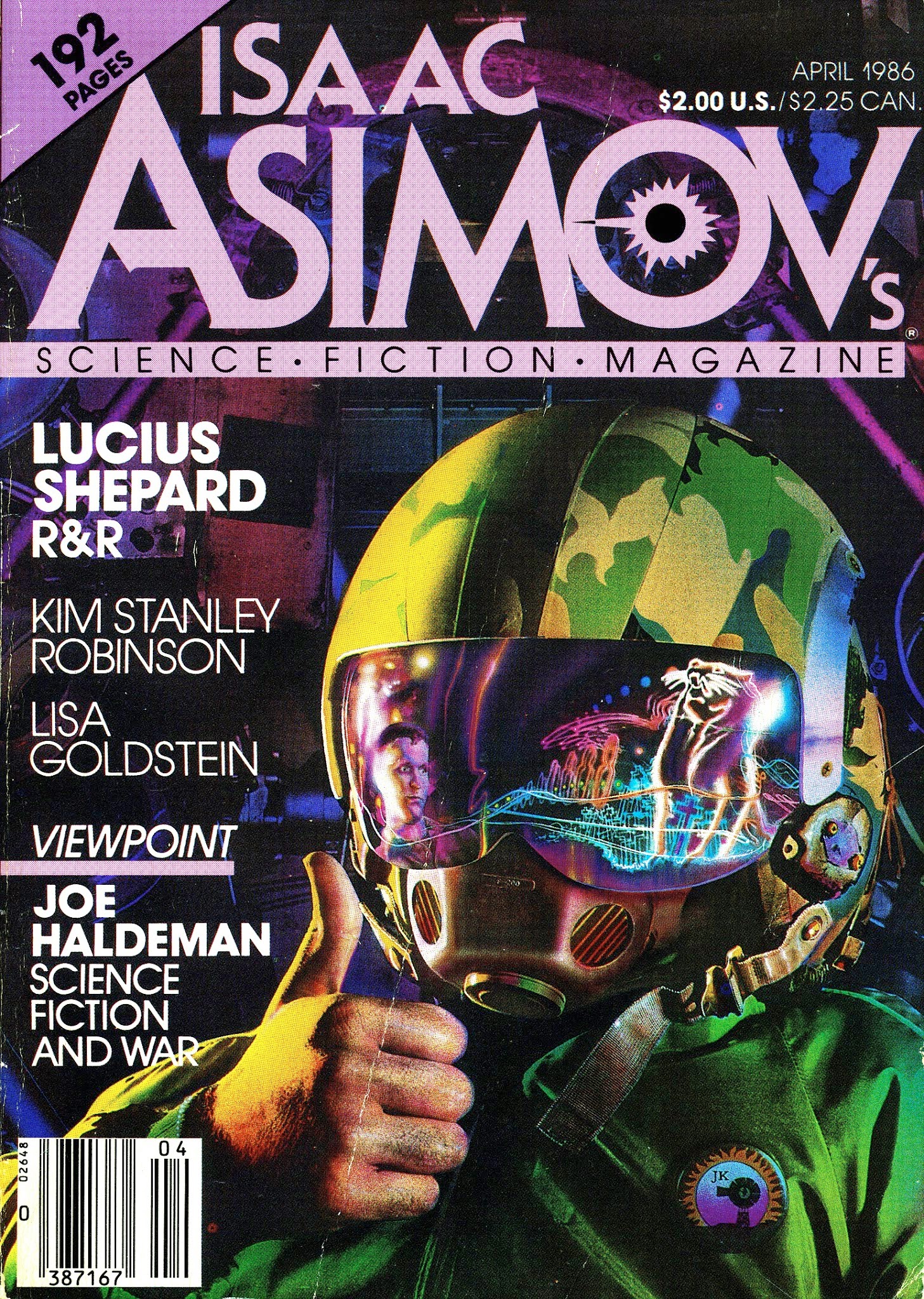

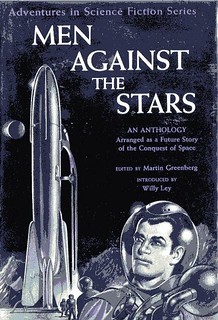

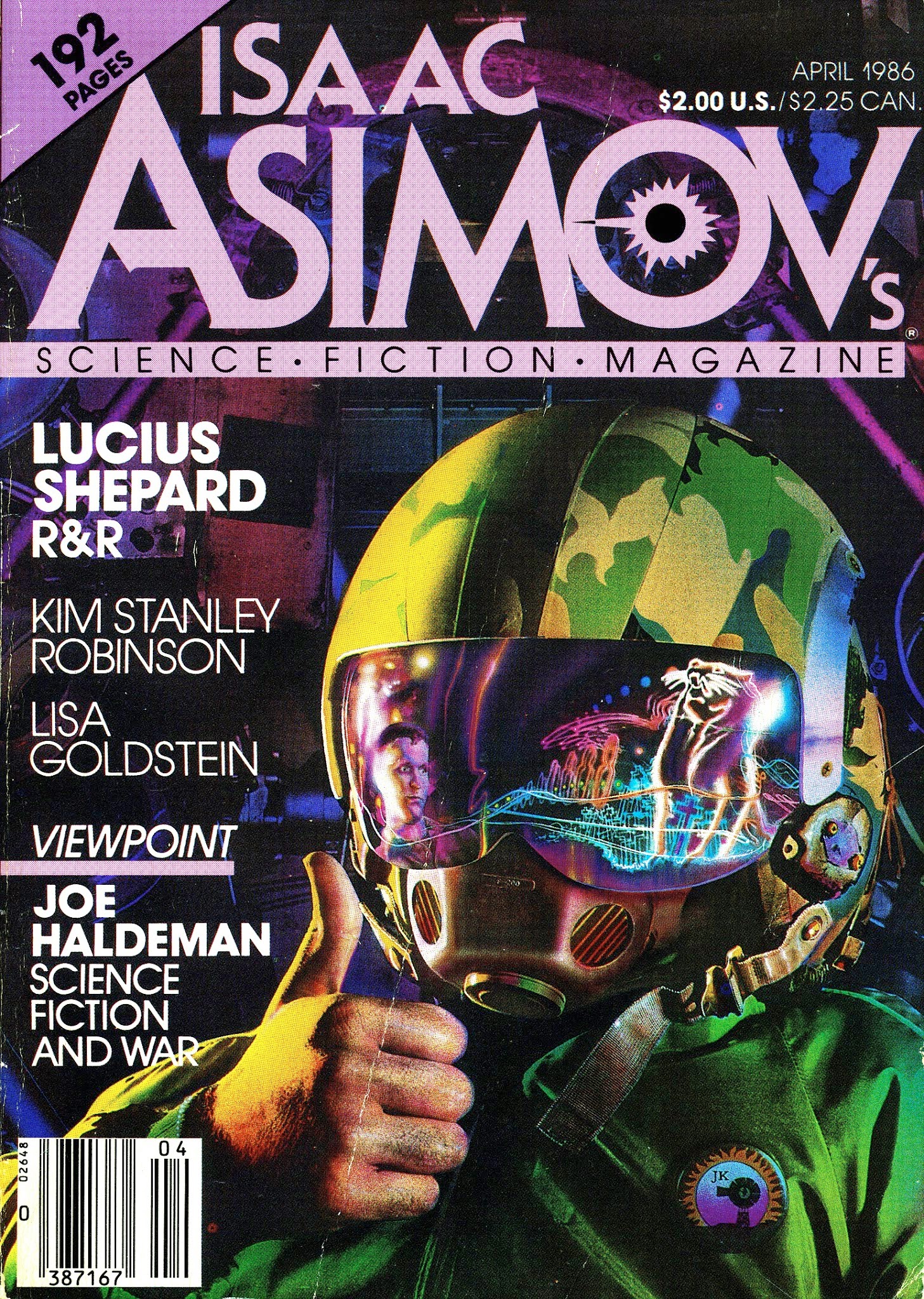

SM: Anyway, that went on until 1960, when I picked up my first adult SF book, an anthology of stories from Astounding called Men Against the Stars, edited by Martin Greenberg, on a holiday in Guernsey. That was quite a life-changing event, as I then spent at least the first half of the 1960s just devouring enormous quantities of SF paperbacks – people like A.E. Van Vogt, Leigh Brackett, Jack Vance, Kenneth Bulmer, New Worlds in the John Carnell era, before it was edited by Mike Moorcock – and although I don’t read a great deal of SF these days, my tastes are still very much influenced by that ‘50s and ‘60s space adventure material. To start with, paperbacks were 2/6d each, and my pocket money was 2/- per week – but by some miracle (or more likely the kindness of my mum) I managed to get a book every week.

SM: Anyway, that went on until 1960, when I picked up my first adult SF book, an anthology of stories from Astounding called Men Against the Stars, edited by Martin Greenberg, on a holiday in Guernsey. That was quite a life-changing event, as I then spent at least the first half of the 1960s just devouring enormous quantities of SF paperbacks – people like A.E. Van Vogt, Leigh Brackett, Jack Vance, Kenneth Bulmer, New Worlds in the John Carnell era, before it was edited by Mike Moorcock – and although I don’t read a great deal of SF these days, my tastes are still very much influenced by that ‘50s and ‘60s space adventure material. To start with, paperbacks were 2/6d each, and my pocket money was 2/- per week – but by some miracle (or more likely the kindness of my mum) I managed to get a book every week.  That was pretty much the start of a collecting mania that these days has filled the entire house with books, though now very little of that’s SF. Just as an aside, back then ‘science fiction’ was always abbreviated as ‘SF’, and anyone who said ‘sci-fi’ was considered a hopeless know-nothing. I suspect that as SF has become more mainstream, the media have enforced a more pronounceable abbreviation, but to someone of my age, ‘sci-fi’ (or worse, ‘syfy’) still grates hideously.

That was pretty much the start of a collecting mania that these days has filled the entire house with books, though now very little of that’s SF. Just as an aside, back then ‘science fiction’ was always abbreviated as ‘SF’, and anyone who said ‘sci-fi’ was considered a hopeless know-nothing. I suspect that as SF has become more mainstream, the media have enforced a more pronounceable abbreviation, but to someone of my age, ‘sci-fi’ (or worse, ‘syfy’) still grates hideously.

Still, getting back to my education. I next went, in 1960, to the Roan School, a boys’ grammar school in Greenwich which, even if it was a bus ride away, was still fairly close at hand. I mainly chose it because they played football rather than rugby, which I didn’t fancy at all – mind you, I never actually wanted to play sport anyway. Still, with a greater interest in the past, these days, I’m actually quite pleased that I went to a school with 400 years of history. Influenced by my space and SF background, I ended up in the science stream, took my GCE O Levels a year early, and then embarked on the first year of A levels in biology, chemistry and physics. By then, of course, I’d discovered that what really interested me about science fiction was actually the fiction, not the science – and I was thoroughly fed up with school anyway – so as soon as I was 16 (barely), I was away [so, probably 1965 - PÓM].  Of course, what little qualification I had was in science subjects, so I ended up working in a laboratory at Rank, Hovis, MacDougall, the flour makers, in Deptford. By the time I’d been there a week, I realised I hated it, but I didn’t know what else to do, so I just retreated further into fantasy – which by then included comics.

Of course, what little qualification I had was in science subjects, so I ended up working in a laboratory at Rank, Hovis, MacDougall, the flour makers, in Deptford. By the time I’d been there a week, I realised I hated it, but I didn’t know what else to do, so I just retreated further into fantasy – which by then included comics.

PÓM: What exactly were you doing at the flour factory?

SM: I was working in the quality control laboratory, attached to the actual mill. We’d get in samples of grain and flour, which needed half a dozen different tests, though I can only remember a couple of them. One was ‘moistures’, where you’d weigh out a certain quantity of the flour into a small, close-topped tin. Then you’d bake a batch of tins in an oven for a couple of hours and weigh them again, and from the difference in the weight you’d work out a percentage for the moisture in the sample that had been driven off in the baking.  The other was ‘proteins’ which entailed boiling the samples in flasks full of sulphuric acid (but I don’t quite remember the details). You’d spend a week working on one test, then move on to another the next, so you weren’t doing the same thing all the time, but it was all very routine. You see why I wanted to get out of there. About the only good thing about it was that they had a games room where you could spend your lunch hour playing snooker or table tennis. And there was a pub a few yards away…

The other was ‘proteins’ which entailed boiling the samples in flasks full of sulphuric acid (but I don’t quite remember the details). You’d spend a week working on one test, then move on to another the next, so you weren’t doing the same thing all the time, but it was all very routine. You see why I wanted to get out of there. About the only good thing about it was that they had a games room where you could spend your lunch hour playing snooker or table tennis. And there was a pub a few yards away…

PÓM: Do you ever regret leaving school so early?

SM: What’s the point of regret? I made a decision almost 50 years ago and there’s no going back to change it. Seriously, though, there was nothing they could have taught me at school that would have helped me in a career as a comic-strip writer. When I was at Odhams I did a day-release course in journalism for several months, and that was completely useless to me as well. On the last day of the course  I presented the lecturer with a copy of my fanzine, Aspect #2, fully typeset and with a colour cover, with professional artists and writers, and he said ‘Why didn’t you show this to us before?’ The answer being, first, that I already knew all the relevant stuff he’d been trying to teach me and, second, I just didn’t want to, as I’d been bored rigid all the way through the course. I think it might just have been a way of showing my contempt for the course that I’d wasted so much time on.

I presented the lecturer with a copy of my fanzine, Aspect #2, fully typeset and with a colour cover, with professional artists and writers, and he said ‘Why didn’t you show this to us before?’ The answer being, first, that I already knew all the relevant stuff he’d been trying to teach me and, second, I just didn’t want to, as I’d been bored rigid all the way through the course. I think it might just have been a way of showing my contempt for the course that I’d wasted so much time on.

Of course there are times when, considering my non-fiction research interests in the classical and oriental worlds, I think it would perhaps have been useful to have gone to university and learned Greek, Latin or Chinese properly, but hindsight is a wonderful thing. And knowing how much I hated school, I doubt I would have had any better time at university. Or that either of those things would have helped me make a living.

PÓM: Now, I wanted to ask you about comics. What comics were you reading at this stage?

SM: As a very young kid I read Robin, the junior companion to Eagle, and then I think I probably had the same line’s Swift, before working my way up to Eagle itself. I seem to recall reading DC Thomson’s The Beezer for a while when it first started (I was probably seduced by the free gifts given away at its launch) and as I said, I then grew into the Eagle, which was my main boyhood comic. I may have read some other stuff, but I don’t recall reading any of the major boys’ adventure comics like Lion or Tiger. I have vague memories of reading the odd copy of Marvelman and Young Marvelman, probably borrowed from other kids at school, but I wasn’t really into comics at primary school. Too busy reading The Boys’ Book of Space!

SM: As a very young kid I read Robin, the junior companion to Eagle, and then I think I probably had the same line’s Swift, before working my way up to Eagle itself. I seem to recall reading DC Thomson’s The Beezer for a while when it first started (I was probably seduced by the free gifts given away at its launch) and as I said, I then grew into the Eagle, which was my main boyhood comic. I may have read some other stuff, but I don’t recall reading any of the major boys’ adventure comics like Lion or Tiger. I have vague memories of reading the odd copy of Marvelman and Young Marvelman, probably borrowed from other kids at school, but I wasn’t really into comics at primary school. Too busy reading The Boys’ Book of Space!

PÓM: Had American comics started to become readily available, and were you reading them?

SM: No. I think American comics weren’t imported into this country before 1960, by which time I was at grammar school and reading ‘grown up’ SF. The first American comic I saw was a copy of Mystery in Space, which my mum (knowing my tastes) bought to cheer me up while I was in bed with some minor illness. I liked it (and Adam Strange has always retained a special place in my affections as a result) but, again, the bug didn’t really bite at the time.

SM: No. I think American comics weren’t imported into this country before 1960, by which time I was at grammar school and reading ‘grown up’ SF. The first American comic I saw was a copy of Mystery in Space, which my mum (knowing my tastes) bought to cheer me up while I was in bed with some minor illness. I liked it (and Adam Strange has always retained a special place in my affections as a result) but, again, the bug didn’t really bite at the time.

PÓM: You were part of the very first wave of British comics fandom, I believe. How did that come about, and how did you become involved in it?

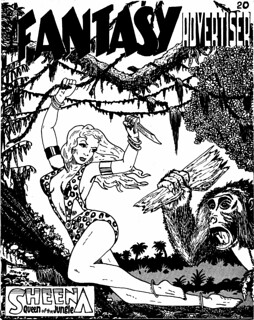

SM: Well, first I was involved with British SF fandom, which was long established – from before World War II, I believe. I think it was about 1964 (maybe 1963) that I joined the British Science Fiction Association (BSFA), probably as a result of seeing an advert in something like New Worlds. At the time there was quite a thriving London ‘scene’, particularly Friday evening meetings at the flat of a woman called Ella Parker, who lived in Kilburn, which I started attending regularly. I made a few contacts there and, while it might be too much to say I got to ‘know’ them, I at least got the chance to meet and hang out with authors like Mike Moorcock, John Brunner, Kenneth Bulmer and E.C. Tubb; and sometimes to share the tube back to Charing Cross with the charming John Carnell. Big thrills for a 15-year-old kid – though obviously I was too young to really make a connection with the professional writers.