new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: creative nonfiction, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 26 - 50 of 456

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: creative nonfiction in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

Biannual magazine Compose: A Journal of Simply Good Writing seeks submissions for their Spring 2016 issue. Accepts fiction, poetry, creative nonfiction, artwork, and feature articles and interviews about the craft of writing. Deadline: January 31, 2016. Guidelines.

First, let me give a big congratulations to Michelle H. who won the CWIM giveaway! I know you will enjoy it.

You know, it isn’t often that something truly innovative comes along in education or publishing.

But when it does, look out!

My post today is about one such unique project called

The Nonfiction Minute (NFM).

Check out the website at www.nonfictionminute.com

Each school day on The Nonfiction Minute website, a fascinating 400-word nonfiction article is published. Each article is written by one of two dozen award-winning nonfiction authors. The articles cover subjects that are as different as each author and include topics in history, sports, popular culture, space, math, government, music, and everything in-between. Related photographs accompany each article. NFM articles can be used to teach content, as well as reading and writing.

But, wait, there’s more.

Every Nonfiction Minute has an audio file of the author reading his or her own article. In this way, young readers or struggling readers can listen as they read along. This feature allows the NFM to work across all age groups from primary grades through adulthood.

But wait, there’s more.

The Nonfiction Minute is FREE! That’s right ladies and gents, FREE.

This revolutionary idea is produced by a group of nonfiction authors called Authors on Call, which is a subset of a larger group known as

iNK Think Tank.

Each article is written by a professional nonfiction author, then edited by a top-tier professional nonfiction editor, Jean Reynolds.

To be fair, I must declare my disclaimer: I am a member of iNK Think Tank, Authors on Call, and I write for The Nonfiction Minute. However, the few articles I’ve written are a small part of the 170 Nonfiction Minutes that will appear in the line-up this school year. I’m part of an ever-growing audience of NFM readers. Every day, the articles written by my fellow authors fascinate me. They capture the imagination of the reader with expertly crafted text in only 400 words.

Vicki Cobb, award-winning author and founder of iNK Think Tank says:

"The Nonfiction Minute illustrates a variety of voices. Authors are not homogeneous. Readers will get to know each author as they read the article then hear the author speak. This too is a learning experience as it demonstrates to students how various authors look at the facts and filter what to use. Kids will see there is a big difference between what they read in a textbook and what they read in The Nonfiction Minute."

This is the second school year for the NFM. Since the beginning there have been around 300,000 page views, from 90,000 unique visitors. Readership is growing fast as more teachers find out about the NFM. At present, there are around 1200 page views per day.

Responding to the needs of teachers who commented they would love to have advance notice of the coming week’s topics on the NFM, Authors on Call provided a way to do just that. Now teachers can receive an email on Thursday of the previous week that lists the article topics for the next week. This way, teachers have time to plan how they can incorporate NFM into their teaching plans. To sign up for advance notice, teachers simply sign up through the website to receive the email--which is, again, FREE.

Great teachers all across America are finding ways to use the NFM with their students. Here are two examples from teachers I know in Arkansas that demonstrate how one article can be used in a variety of ways. These two teachers used a recent NFM I wrote titled “The Near-Death Experience of Football.” The article deals with the deadly 1905 football season when America considered banning the game, and President Teddy Roosevelt called coaches to a meeting in hopes of saving football. The same article, two different teachers, two different age groups:

Melissa L., a media specialist in a tiny rural school, explained how she used this NFM with her 5th grade students:

"I have a big screen tv at the front of my library (got it before we began purchasing Smart Boards) which is connected to my computer. So I pull up the website at the beginning of each period along with any other peripheral webpages on info that I think may come into our discussion afterwards (for instance, this week I pulled up what the Ivy League Schools are on Wikipedia and we looked at their names and the years they were founded as well as Google images of football uniforms around the early 1900's - which led to a discussion of the dangers of even SIMPLE injuries in the days before "modern medicine."). I also pull up a tab with a page for the author that has an image of the books that he/she has written - to introduce the kids to that person before we begin the Nonfiction Minute. Then I turn up my audio and enlarge the words on my screen as big as I can so that at least the closest ones can read along (as I scroll) while the author reads aloud. When done I then close that screen and have the discussion with questions about what we just listened to and learned - and any peripheral discussion (as I just mentioned). In all it takes 5-10 minutes at the beginning of class."

The next example is from Cassandra S., an 8th grade English teacher:

"I'm using this article and another one like it to discuss Teddy Roosevelt's involvement with saving football (leading to a discussion and writing prompt about presidents exerting personal preferences into national policies) which will then lead us to discussing Andrew Jackson's controversial decisions upon election and again...accountability for presidents and their personal motives. (This second portion is to supplement my struggling readers in the American History class while focusing on argumentative writing in mine)."

What I love about the above samples is that each teacher used the same NFM and found creative, effective ways to use it that fit the needs of her students. Perhaps best of all, these amazing teachers guided their students in a way that encouraged them to use critical thinking skills.

Gone are the days when nonfiction equals boring. Finally, nonfiction texts are available that are fun, fascinating, and free. We the authors of The Nonfiction Minute hope great teachers around the country will use our work to promote a passion for learning.

So, spread the word about this truly innovative project.

Teachers and students will enjoy every minute.

Carla Killough McClafferty

<!--[if gte mso 9]>

Normal 0 false false false EN-US JA X-NONE <![endif]-->

Online literary magazine Cargo focuses on narrative and growth through travel and exploration. Seeks creative nonfiction, memoir, personal essay, poetry, book reviews, visual art, and photography. Prefers work that evokes a strong sense of character, setting, movement, and the internal journey — writing that asks us to slow down and consider our past for a moment. Deadline: Rolling. Guidelines.

As I write nonfiction books, I carefully consider sentence length and punctuation. Every sentence is crafted in a way that will support the pacing of my (true) story. Does sentence structure and punctuation affect the pacing of the story? Absolutely! How you write the text makes all the difference.

As an example, let’s consider the opening scene from my book,

Fourth Down and Inches:

Concussions and Football’s Make-or-Break Moment

I could have begun this book in countless ways. I chose to begin the book with a young man named Von Gammon because I believe it sets the scene for the whole book. I wanted to pull the reader in by giving them a glimpse into Von’s life. Once I decided to open the book with this young man, there were countless ways I could have written the scene.

Consider the following examples and choose which is more compelling:

EXAMPLE 1

Von Gammon lay down on the grass. He told his brother to stand on his hands. Von was strong and could prove it. He could lift his brother who was six feet six inches tall off the ground. Von was strong and skilled.

OR…

EXAMPLE 2

Von Gammon lay down on the grass and told his brother to stand on his hands. Von was strong, and he could prove it. Then he lifted his brother—all six feet and six inches of him—clear off the ground. And Von wasn’t just strong; he was skilled.

The second example is what appears in the published book. The first example communicates the same information, but doesn’t pull the reader into the story. The difference is in the sentence structure and punctuation.

Just a few sentences later, I write about the moment things changed for Von. Which of the following is more interesting?

EXAMPLE 1

When Von was a sophomore, he played in a football game that took place on October 30. He was on the University of George team and they were playing the University of Virginia. Von’s team was behind by seven points. The other team had control of the ball. Von was a defensive lineman. When the ball was snapped and the play began, the linemen hit each other. Von laid on the field after all the other players walked away.

OR…

EXAMPLE 2

On October 30 of Von’s sophomore year, the Georgia Bulldogs were battling the University of Virginia. They trailed by seven points, and Virginia had the ball. Von took his place on the defensive line. The center snapped the ball. A mass of offensive linemen lurched toward Von, and he met them with equal force.

The play ended in a stack of tangled bodies.

One by one, the Virginia players got up and walked away. Von didn’t.

The second example appears in the published book. Again it isn’t the information that is different; it is how the information is presented that is different.

Why did I begin

Fourth Down and Inches:

Concussions and Football's Make-or-Break Moment

with Von Gammon?

Because Von sustained a concussion and died a few hours later. His death caused many to wonder if football was too dangerous.

The year was 1897.

Carla Killough McClafferty

BOOK GIVEAWAY!

Win an autographed copy Baby Says “Moo!” by JoAnn Early Macken. For more details on the book and enter the book giveaway, see her blog entry on June 12, 2015. The giveaway runs through June 22. The winner will be announced on June 26.

As a researcher, one of the places that inspire me is the Library of Congress (LOC). The building itself is a national treasure, but the collections it holds are even more precious. No matter what you are interested in, chances are that the Library of Congress has some material that relates to it. It is a gold mine of primary source material for teachers, students, and writers.

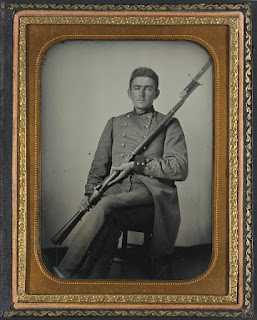

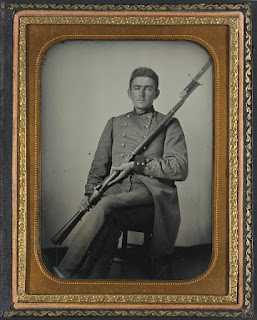

The LOC has a vast amount of material online, but let me give you an example of just one small slice of it. Let’s take photographs from the Civil War. When I look at this collection I see powerful, amazing images of people on both sides of the war. While I’m interested in photos of the famous people like Lincoln, Lee and Grant, I’m even more fascinated by images of average soldiers who are often unidentified. When I look at their faces, I wonder what they experienced and if they survived the war.

Photos of soldiers are not the only type of images in their collection; many are of women and children. This touching image of a young girl in a dark mourning dress holding a photo of her father, says a lot-silently.

This morning I found an unexpected collection at the LOC: eyewitness drawings of Civil War scenes. There are lots of battle scenes and landscapes, but the one that drew my eye was this sketch of a soldier. It makes me wonder who this man was and why the artist sketched his image. Was he a friend or brother? Was he a hero or a deserter?

Images like these can teach students a lot about history. And they can inspire both fiction and nonfiction writers.

Carla Killough McClafferty

http://www.loc.gov/

The last few posts from my fellow TeachingAuthors have been on poetry. Each of them has written eloquently on the topic. But trust me when I tell you that I have nothing worthwhile to contribute to the topic of poetry. So, I’ll share a topic with you that I do know about: research.

I enjoy sharing how to do research with students and teachers. I offer a variety of program options including several different types of sessions on brainstorming, research, and writing. I love to be invited into a school for a live author visit. But that isn’t always possible. In the last couple of years, I’ve done lots of Interactive Video Conferences as part of the Authors on Call group of inkthinktank.com.

During these video conferences, I’ve come up with ways to teach students from third grade through high school how to approach a research project. One method I use is to give them an easy way to remember the steps to plan their research using A, B, C, and D:

A

ALWAYS CHOOSE A TOPIC THAT INTERESTS YOU.

B

BRAINSTORM FOR IDEAS THAT WILL MAKE YOUR PAPER DIFFERENT FROM EVERY OTHER PAPER.

C

CHOOSE AN ANGLE FOR YOUR PAPER AND WRITE A ONE SENTENCE PLAN THAT BEGINS:

MY PAPER IS ABOUT . . .

D

DECIDE WHERE TO FIND THE RESEARCH INFORMATION THAT FITS THE ANGLE OF YOUR PAPER.

The earlier students learn good research skills, the better. Learning some tips and tricks like my ABCD plan will help. I hope it makes the whole process less daunting.

Carla Killough McClafferty

To find out more about booking an Interactive Video Conference with students or teachers:

Contact Carla Killough McClaffertyiNK THINK TANK Center for Interactive Learning and Collaboration (search for mcclafferty or inkthinktank)

Readers of

Handling the Truth: On the Writing of Memoir know that—while I greatly vary the way I teach, the books I share, and the writers I invite to the classroom—there is one consistent essay I assign early-ish in the teaching season. A 750-word response designed to shake out ideas, ideals, and possibilities.

This year My Spectaculars produced such extraordinarily charming and elucidating responses to the assignment that I decided (with my students' permission) to knit together elements so that we might always have a record of Us. I've called the piece "How to Write a Memoir. Or (The Expectations Virtues)" and shared it on Huffington Post.

The piece, which begins like this, can be found in its entirety

here. I call them My Spectaculars. Together, we read, we write. We rive our hearts. We leave faux at the door. We expect big things from one another, from the memoirists we read, from the memoirists who may be writing now, from those books of truth in progress.

But what do we mean by that word, expectation?

It's a question I require my University of Pennsylvania Creative Nonfiction students to answer. A conversation we very deliberately have. What do you expect of the writers you read, and what do you expect of yourselves?

This year, again, I have been chastened, made breathless, by the rigor and transparency of my most glorious clan. By Anthony, for example, who declares up front, no segue: ......

(Read on, I exhort you. Find out.)

There is a single student voice missing from this tapestry—my Sarah. You are going to be hearing from her next week or so, after a page or two of her brilliance is published and cross-linked here. Trust me, you will be changed by Sarah's words.

For now, I leave you my students. Read, and you'll call them Spectaculars, too.

By:

Carmela Martino and 5 other authors,

on 2/27/2015

Blog:

Teaching Authors

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Flip Float Fly: Seeds on the Move,

Marcie Flinchum Atkins,

Poetry Friday,

Nonfiction,

April Pulley Sayre,

Laura Purdie Salas,

creative nonfiction,

JoAnn Early Macken,

Lola Schaefer,

Fiona Bayrock,

Add a tag

In this series of Teaching Author posts, we’re discussing the areas of overlap between fiction and nonfiction. Today, I’m thinking about creative nonfiction.

What is Creative Nonfiction? According to Lee Gutkind (known as the “Father of Creative Nonfiction”), “The words ‘creative’ and ‘nonfiction’ describe the form. The word ‘creative’ refers to the use of literary craft, the techniques fiction writers, playwrights, and poets employ to present nonfiction—factually accurate prose about real people and events—in a compelling, vivid, dramatic manner. The goal is to make nonfiction stories read like fiction so that your readers are as enthralled by fact as they are by fantasy.”

One critical point about writing creative nonfiction is that creativity does not apply to the facts. Authors cannot invent dialog, combine characters, fiddle with time lines, or in any other way divert from the truth and still call it nonfiction. The creative part applies only to the way factual information is presented.

One way to present nonfiction in a compelling, vivid manner is to take advantage of the techniques of poetry. When I wrote the nonfiction picture book

Flip, Float, Fly: Seeds on the Move (gorgeously illustrated by

Pam Paparone), I made a conscious effort to use imagery, alliteration, repetition, and onomatopoeia while explaining how seeds get around. When she called with the good news, the editor called it a perfect blend of nonfiction and poetry. Yippee, right?

Fiona Bayrock’s

“Eleven Tips for Writing Successful Nonfiction for Kids” lists more helpful and age-appropriate methods for grabbing kids’ attention, starting with “Tap into your Ew!, Phew!, and Cool!”

Marcie Flinchum Atkins has compiled a helpful list of ten

Nonfiction Poetic Picture Books. She points out that these excellent books (including some by

Teaching Authors friends

April Pulley Sayre,

Laura Purdie Salas, and

Lola Schaefer) can be used in classrooms to teach good writing skills. We can all learn from such wonderful examples!

Heidi Mordhorst has this week’s Poetry Friday Roundup at

My Juicy Little Universe. Enjoy!

JoAnn Early Macken

By: Jessica Strawser,

on 2/24/2015

Blog:

Guide to Literary Agents

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

craft/technique,

Craft & Technique,

Marketing & Self-Promotion,

There Are No Rules Blog by the Editors of Writer's Digest,

personal writing,

jessica strawser,

WD Magazine,

Industry News & Trends,

General,

Getting Published,

memoir,

creative nonfiction,

narrative nonfiction,

What's New,

Add a tag

I had a dear friend who had a gift for telling stories about her day. She’d launch into one, and suddenly everyone around her would hush up and lean in, knowing that whatever followed would be pure entertainment. A story of encountering a deer on the highway would involve interludes from the deer’s point of view. Strangers who factored into her tales would get nicknames and imagined backstories of their own. She could make even the most mundane parts of her day—and everyone else’s—seem interesting. She didn’t aspire to be a writer, but she was a born storyteller.

I had a dear friend who had a gift for telling stories about her day. She’d launch into one, and suddenly everyone around her would hush up and lean in, knowing that whatever followed would be pure entertainment. A story of encountering a deer on the highway would involve interludes from the deer’s point of view. Strangers who factored into her tales would get nicknames and imagined backstories of their own. She could make even the most mundane parts of her day—and everyone else’s—seem interesting. She didn’t aspire to be a writer, but she was a born storyteller.

Why All Nonfiction Should Be Creative Nonfiction

The term creative nonfiction often brings to mind essays that read like poems, memoirs that read like novels, a lyrical way of interpreting the world around us. But the truth is that writing nonfiction—from blog posts to routine news reports to business guides—can (and should) be creative work. And the more creativity you bring to any piece, the better it’s likely to be received, whether your target reader is a friend, a website visitor, an editor or agent, or the public at large.

The March/April 2015 Writer’s Digest goes on sale today—and this issue delves into the creative sides of many types of nonfiction.

- Learn seven ways to take a creative approach to any nonfiction book—whether you wish to write a self-help title, a historical retelling, a how-to guide, or something else entirely.

- Get tips for finding the right voice for your essays, memoirs and other true-to-life works—and see how it’s that voice above all else that can make or break your writing.

- Delve into our introduction to the nonfiction children’s market—where writers can earn a steady income by opening kids’ eyes to the world around them.

- And find out what today’s literary agents and publishers are looking for in the increasingly popular narrative nonfiction genre—where books ranging from Rebecca Skloot’s The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks to Roxane Gay’s Bad Feminist to Susan Cain’s Quiet have been reinvigorating the bestseller lists.

Why Readers Love True Stories

“Narrative nonfiction has become more in-demand because it provides additional value; it’s entertaining and educational,” explains agent Laurie Abkemeier in our narrative nonfiction roundtable. “There are many forms of entertainment vying for our attention, and the ones that give us the highest return for our time and money investment are the ones that we gravitate toward.”

So give your readers that amazing return. The articles packed into this informative, diverse and boundary-pushing issue will show you how. Download the complete issue right now, order a print copy, or find it on your favorite newsstand through mid-April.

Jessica Strawser

Editor, Writer’s Digest Magazine

Follow me on Twitter @jessicastrawser

riverSedge is a journal of art and literature with an understanding of its place in the nation in south Texas on the border . Its name reflects our specific river edge with an openness to publish writers who use English, Tex-Mex, and Spanish and also the edges shared by all the best contemporary writing and art.

Submit here.

General Submissions/Contest Guidelines

Deadline to Submit is 3/1/15

$5 submission fee in all genres (except book reviews)

3 prizes of $300 will be awarded in poetry, prose, and art. All entries are eligible for contest prizes. Dramatic scripts and graphic literature will be judged as prose.

Multiple submissions are welcome in all genres. Each submission should be submitted as a separate entry. In other words, do not send two or more entries as one document.

Previously unpublished work only. Self-published work (in print and/or on the web) is not eligible.

Simultaneous submissions are welcome, but please notify us of acceptance elsewhere as soon as possible.

Submissions in English, Spanish and anything in between are welcome.

Current staff, faculty, and students affiliated with UT-Pan American, UT-Brownsville, or South Texas College are not eligible to submit original work to riverSedge.

Jabberwock Review invites submissions to:

THE NANCY D. HARGROVE EDITORS’ PRIZE FOR FICTION AND POETRY

DEADLINE: March 15, 2015

· Each winner (one for fiction and one for poetry) receives $500 and publication in Jabberwock Review.

· Entry Fee: $15, which includes a one-year subscription.

· Go to our website for more information and to submit using Submittable.

· We are also open for regular submissions in fiction, poetry, and creative nonfiction. Send us your best work!

The Quotable Lit is open for Issue 17: Atmosphere

Submissions open January 1, 2015 – March 1, 2015

“Green was the silence, wet was the light,the month of June trembled like a butterfly.”

― Pablo Neruda

General Guidelines:

We seek:

flash fiction (under 1,000 words) - 1 submission per reading period

short fiction (under 3,000 words) - 1 submission per reading period

creative nonfiction (under 3,000 words) - 1 submission per reading period

poetry - 1 submission of up to 3 poems per reading period

We accept only original unpublished work. We do accept simultaneous submissions, but ask that you notify us immediately should your work be accepted elsewhere.

Submissions link.

To ensure fairness, The Quotable has a blind submissions process. Remove all identifying information - name, email address, etc. - from your manuscripts. We will decline any manuscript that contains the author's information. Contact us with questions.

Upon acceptance, The Quotable acquires first serial publications rights, after which the copyright reverts to the author. All accepted work will be archived on the site for so long as the site manager(s) should deem appropriate.

The editors of The Quotable envision a world in which all artists are paid handsomely for the considerable efforts they make to enrich mankind. While we labor toward that utopia, however, the only payment we can offer is the esteem of seeing your name in print and your work appreciated

The Account: A Journal of Poetry, Prose, and Thought is reading submissions for a special Spring ’15 issue: “Graphic Works/Graphic Narratives.” We’re seeking graphic narratives, illuminated manuscripts, rebuses, illustrations evocative of stories, and poems that interact with the page as a visual landscape (such as concrete poems, erasures, and prose poems). Please submit work via Submittable by March 15th for consideration. The Account does not have a reading fee. However, we do require work to be paired with an “account” (of 150–500 words) that describes the thought, influences, and choices that make up your aesthetic as it pertains to the specific work you send us. account = history, sketch, marker, repository of influences

An account of a specific work traces its arc—through texts and world—while giving voice to the artist’s approach. We ask that if you choose to be satirical, you do so in service of the work you are submitting. We are most interested in how you are tracking the thought, influences, and choices that make up your aesthetic as it pertains to a specific work.

Please use Submittable to submit. We will not consider work without an account. We do read simultaneous submissions. You may still submit work under one of our general categories for a later issue.

General Information

Please review The Account: A Journal of Poetry, Prose, and Thought submission guidelines for poetry, fiction, and nonfiction. We will not consider work submitted without an account. Simultaneous submissions are welcome, but your work must be withdrawn immediately if it is no longer available. Authors retain their copyright and will receive a contract upon acceptance.

Criticism operates on a solicitation-only basis.

Art currently operates on a solicitation-only basis. However, if you are interested in sending us a work sample, CV, and query letter, you are welcome to email us:

poetryprosethoughtATgmailDOTcom (Change AT to @ and DOT to . )

The following is an excerpt from Word Painting Revised Edition by Rebecca McClanahan, available now!

The following is an excerpt from Word Painting Revised Edition by Rebecca McClanahan, available now!

The characters in our stories, songs, poems, and essays embody our writing. They are our words made flesh. Sometimes they even speak for us, carrying much of the burden of plot, theme, mood, idea, and emotion. But they do not exist until we describe them on the page. Until we anchor them with words, they drift, bodiless and ethereal. They weigh nothing; they have no voice. Once we’ve written the first words—“Belinda Beatrice,” perhaps, or “the dark-eyed salesman in the back of the room,” or simply “the girl”—our characters begin to take form. Soon they’ll be more than mere names. They’ll put on jeans or rubber hip boots, light thin cigarettes or thick cigars; they’ll stutter or shout, buy a townhouse on the Upper East Side or a studio in the Village; they’ll marry for life or survive a series of happy affairs; they’ll beat their children or embrace them. What they become, on the page, is up to us.

Here are 11 secrets to keep in mind as you breathe life into your characters through description.

1. Description that relies solely on physical attributes too often turns into what Janet Burroway calls the “all-points bulletin.”

It reads something like this: “My father is a tall, middle-aged man of average build. He has green eyes and brown hair and usually wears khakis and oxford shirts.”

This description is so mundane, it barely qualifies as an “all-points bulletin.” Can you imagine the police searching for this suspect? No identifying marks, no scars or tattoos, nothing to distinguish him. He appears as a cardboard cutout rather than as a living, breathing character. Yes, the details are accurate, but they don’t call forth vivid images. We can barely make out this character’s form; how can we be expected to remember him?

When we describe a character, factual information alone is not sufficient, no matter how accurate it might be. The details must appeal to our senses. Phrases that merely label (like tall, middle-aged, and average) bring no clear image to our minds. Since most people form their first impression of someone through visual clues, it makes sense to describe our characters using visual images. Green eyes is a beginning, but it doesn’t go far enough. Are they pale green or dark green? Even a simple adjective can strengthen a detail. If the adjective also suggests a metaphor—forest green, pea green, or emerald green—the reader not only begins to make associations (positive or negative) but also visualizes in her mind’s eye the vehicle of the metaphor—forest trees, peas, or glittering gems.

2. The problem with intensifying an image only by adjectives is that adjectives encourage cliché.

It’s hard to think of adjective descriptors that haven’t been overused: bulging or ropy muscles, clean-cut good looks, frizzy hair. If you use an adjective to describe a physical attribute, make sure that the phrase is not only accurate and sensory but also fresh. In her short story “Flowering Judas,” Katherine Anne Porter describes Braggioni’s singing voice as a “furry, mournful voice” that takes the high notes “in a prolonged painful squeal.” Often the easiest way to avoid an adjective-based cliché is to free the phrase entirely from its adjective modifier. For example, rather than describing her eyes merely as “hazel,” Emily Dickinson remarked that they were “the color of the sherry the guests leave in the glasses.”

3. Strengthen physical descriptions by making details more specific.

In my earlier “all-points bulletin” example, the description of the father’s hair might be improved with a detail such as “a military buzz-cut, prickly to the touch” or “the aging hippie’s last chance—a long ponytail striated with gray.” Either of these descriptions would paint a stronger picture than the bland phrase brown hair. In the same way, his oxford shirt could become “a white oxford button-down that he’d steam-pleated just minutes before” or “the same style of baby blue oxford he’d worn since prep school, rolled carelessly at the elbows.” These descriptions not only bring forth images, they also suggest the background and the personality of the father.

4. Select physical details carefully, choosing only those that create the strongest, most revealing impression.

One well-chosen physical trait, item of clothing, or idiosyncratic mannerism can reveal character more effectively than a dozen random images. This applies to characters in nonfiction as well as fiction. When I write about my grandmother, I usually focus on her strong, jutting chin—not only because it was her most dominant feature but also because it suggests her stubbornness and determination. When I write about Uncle Leland, I describe the wandering eye that gave him a perpetually distracted look, as if only his body was present. His spirit, it seemed, had already left on some journey he’d glimpsed peripherally, a place the rest of us were unable to see. As you describe real-life characters, zero in on distinguishing characteristics that reveal personality: gnarled, arthritic hands always busy at some task; a habit of covering her mouth each time a giggle rises up; a lopsided swagger as he makes his way to the horse barn; the scent of coconut suntan oil, cigarettes, and leather each time she sashays past your chair.

5. A character’s immediate surroundings can provide the backdrop for the sensory and significant details that shape the description of the character himself.

If your character doesn’t yet have a job, a hobby, a place to live, or a place to wander, you might need to supply these things. Once your character is situated comfortably, he may relax enough to reveal his secrets. On the other hand, you might purposely make your character uncomfortable—that is, put him in an environment where he definitely doesn’t fit, just to see how he’ll respond. Let’s say you’ve written several descriptions of an elderly woman working in the kitchen, yet she hasn’t begun to ripen into the three-dimensional character you know she could become. Try putting her at a gay bar on a Saturday night, or in a tattoo parlor, or (if you’re up for a little time travel) at Appomattox, serving her famous buttermilk biscuits to Grant and Lee.

6. In describing a character’s surroundings, you don’t have to limit yourself to a character’s present life.

Early environments shape fictional characters as well as flesh-and-blood people. In Flaubert’s description of Emma Bovary’s adolescent years in the convent, he foreshadows the woman she will become, a woman who moves through life in a romantic malaise, dreaming of faraway lands and loves. We learn about Madame Bovary through concrete, sensory descriptions of the place that formed her. In addition, Flaubert describes the book that held her attention during mass and the images that she particularly loved—a sick lamb, a pierced heart.

Living among those white-faced women with their rosaries and copper crosses, never getting away from the stuffy schoolroom atmosphere, she gradually succumbed to the mystic languor exhaled by the perfumes of the altar, the coolness of the holy-water fonts and the radiance of the tapers. Instead of following the Mass, she used to gaze at the azure-bordered religious drawings in her book. She loved the sick lamb, the Sacred Heart pierced with sharp arrows, and poor Jesus falling beneath His cross.

7. Characters reveal their inner lives—their preoccupations, values, lifestyles, likes and dislikes, fears and aspirations—by the objects that fill their hands, houses, offices, cars, suitcases, grocery carts, and dreams.

In the opening scenes of the film The Big Chill, we’re introduced to the main characters by watching them unpack the bags they’ve brought for a weekend trip to a mutual friend’s funeral. One character has packed enough pills to stock a drugstore; another has packed a calculator; still another, several packages of condoms. Before a word is spoken—even before we know anyone’s name—we catch glimpses of the characters’ lives through the objects that define them.

What items would your character pack for a weekend away? What would she use for luggage? A leather valise with a gold monogram on the handle? An old accordion case with decals from every theme park she’s visited? A duffel bag? Make a list of everything your character would pack: a “Save the Whales” T-shirt; a white cotton nursing bra, size 36D; a breast pump; a Mickey Mouse alarm clock; a photograph of her husband rocking a child to sleep; a can of Mace; three Hershey bars.

8. Description doesn’t have to be direct to be effective.

Techniques abound for describing a character indirectly, for instance, through the objects that fill her world. Create a grocery list for your character—or two or three, depending on who’s coming for dinner. Show us the character’s credit card bill or the itemized deductions on her income tax forms. Let your character host a garage sale and watch her squirm while neighbors and strangers rifle through her stuff. Which items is she practically giving away? What has she overpriced, secretly hoping no one will buy it? Write your character’s Last Will and Testament. Which niece gets the Steinway? Who gets the lake cottage—the stepson or the daughter? If your main characters are divorcing, how will they divide their assets? Which one will fight hardest to keep the dog?

9. To make characters believable to readers, set them in motion.

The earlier “all-points bulletin” description of the father failed not only because the details were mundane and the prose stilted; it also suffered from lack of movement. To enlarge the description, imagine that same father in a particular setting—not just in the house but also sitting in the brown recliner. Then, because setting implies time as well as place, choose a particular time in which to place him. The time may be bound by the clock (six o’clock, sunrise, early afternoon) or bound only by the father’s personal history (after the divorce, the day he lost his job, two weeks before his sixtieth birthday).

Then set the father in motion. Again, be as specific as possible. “Reading the newspaper” is a start, but it does little more than label a generic activity. In order for readers to enter the fictional dream, the activity must be shown. Often this means breaking a large, generic activity into smaller, more particular parts: “scowling at the Dow Jones averages,” perhaps, or “skimming the used-car ads” or “wiping his ink-stained fingers on the monogrammed handkerchief.” Besides providing visual images for the reader, specific and representative actions also suggest the personality of the character, his habits and desires, and even the emotional life hidden beneath the physical details.

10. Verbs are the foot soldiers of action-based description.

However, we don’t need to confine our use of verbs to the actions a character performs. Well-placed verbs can sharpen almost any physical description of a character. In the following passage from Marilynne Robinson’s novel Housekeeping, verbs enliven the description even when the grandmother isn’t in motion.

… in the last years she continued to settle and began to shrink. Her mouth bowed forward and her brow sloped back, and her skull shone pink and speckled within a mere haze of hair, which hovered about her head like the remembered shape of an altered thing. She looked as if the nimbus of humanity were fading away and she were turning monkey. Tendrils grew from her eyebrows and coarse white hairs sprouted on her lip and chin. When she put on an old dress the bosom hung empty and the hem swept the floor. Old hats fell down over her eyes. Sometimes she put her hand over her mouth and laughed, her eyes closed and her shoulder shaking.

Notice the strong verbs Robinson uses throughout the description. The mouth “bowed” forward; the brow “sloped” back; the hair “hovered,” then “sprouted”; the hem “swept” the floor; hats “fell” down over her eyes. Even when the grandmother’s body is at rest, the description pulses with activity. And when the grandmother finally does move—putting a hand over her mouth, closing her eyes, laughing until her shoulders shake—we visualize her in our mind’s eye because the actions are concrete and specific. They are what the playwright David Mamet calls “actable actions.” Opening a window is an actable action, as is slamming a door. “Coming to terms with himself” or “understanding that he’s been wrong all along” are not actable actions. This distinction between nonactable and actable actions echoes our earlier distinction between showing and telling. For the most part, a character’s movements must be rendered concretely—that is, shown—before the reader can participate in the fictional dream.

Actable actions are important elements in many fiction and nonfiction scenes that include dialogue. In some cases, actions, along with environmental clues, are even more important to character development than the words the characters speak. Writers of effective dialogue include pauses, voice inflections, repetitions, gestures, and other details to suggest the psychological and emotional subtext of a scene. Journalists and other nonfiction writers do the same. Let’s say you’ve just interviewed your cousin about his military service during the Vietnam War. You have a transcript of the interview, based on audio or video recordings, but you also took notes about what else was going on in that room. As you write, include nonverbal clues as well as your cousin’s actual words. When you asked him about his tour of duty, did he look out the window, light another cigarette, and change the subject? Was it a stormy afternoon? What song was playing on the radio? If his ancient dog was asleep on your cousin’s lap, did he stroke the dog as he spoke? When the phone rang, did your cousin ignore it or jump up to answer it, looking relieved for the interruption? Including details such as these will deepen your character description.

11. We don’t always have to use concrete, sensory details to describe our characters, and we aren’t limited to describing actable actions.

The novels of Milan Kundera use little outward description of characters or their actions. Kundera is more concerned with a character’s interior landscape, with what he calls a character’s “existential problem,” than with sensory description of person or action. In The Unbearable Lightness of Being, Tomas’s body is not described at all, since the idea of body does not constitute Tomas’s internal dilemma. Teresa’s body is described in physical, concrete terms (though not with the degree of detail most novelists would employ) only because her body represents one of her existential preoccupations. For Kundera, a novel is more a meditation on ideas and the private world of the mind than a realistic depiction of characters. Reading Kundera, I always feel that I’m living inside the characters rather than watching them move, bodily, through the world.

With writers like Kundera, we learn about characters through the themes and obsessions of their inner lives, their “existential problems” as depicted primarily through dreams, visions, memories, and thoughts. Other writers probe characters’ inner lives through what characters see through their eyes. A writer who describes what a character sees also reveals, in part, a character’s inner drama. In The Madness of a Seduced Woman, Susan Fromberg Schaeffer describes a farm through the eyes of the novel’s main character, Agnes, who has just fallen in love and is anticipating her first sexual encounter, which she simultaneously longs for and fears.

… and I saw how the smooth, white curve of the snow as it lay on the ground was like the curve of a woman’s body, and I saw how the farm was like the body of a woman which lay down under the sun and under the freezing snow and perpetually and relentlessly produced uncountable swarms of living things, all born with mouths open and cries rising from them into the air, long-boned muzzles opening … as if they would swallow the world whole …

Later in the book, when Agnes’s sexual relationship has led to pregnancy, then to a life-threatening abortion, she describes the farm in quite different terms.

It was August, high summer, but there was something definite and curiously insubstantial in the air. … In the fields near me, the cattle were untroubled, their jaws grinding the last of the grass, their large, fat tongues drinking the clear brook water. But there was something in the air, a sad note the weather played upon the instrument of the bone-stretched skin. … In October, the leaves would be off the trees; the fallen leaves would be beaten flat by heavy rains and the first fall of snow. The bony ledges of the earth would begin to show, the earth’s skeleton shedding its unnecessary flesh.

By describing the farm through Agnes’s eyes, Schaeffer not only shows us Agnes’s inner landscape—her ongoing obsession with sex and pregnancy—but also demonstrates a turning point in Agnes’s view of sexuality. In the first passage, which depicts a farm in winter, Agnes sees images of beginnings and births. The earth is curved and full like a woman’s fleshy body. In the second scene, described as occurring in “high summer,” images of death prevail. Agnes’s mind jumps ahead to autumn, to dying leaves and heavy rains, a time when the earth, no longer curved in a womanly shape, is little more than a skeleton, having shed the flesh it no longer needs.

The Antioch University Los Angeles Creative Writing MFA program's bimonthly publication, Amuse-Bouche, is accepting submissions for its upcoming issues. Poetry, Fiction, Creative Nonfiction, YA, Translation, and Visual Art submissions are all welcome.

Visit Lunch Ticket's website for submission guidelines (please read guidelines CAREFULLY before submitting).

Deadline: January 31st, 2015.

By: Jeanne Lyet Gassman,

on 1/7/2015

Blog:

Jeanne's Writing Desk

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Book News,

Fiction,

Essays,

Nonfiction,

Mystery,

YA Fiction,

Submissions,

Creative Nonfiction,

Narrative Nonfiction,

Short Story Collections,

Add a tag

Ashland Creek Press Seeks Work on Environment & Animal Protection

Deadline: Year-Round

Ashland Creek Press is currently accepting submissions of book-length fiction and nonfiction on the themes of the environment, animal protection, ecology, and wildlife—above all, we’re looking for exceptional, well-written, engaging stories.

We are open to many genres (young adult, mystery, literary fiction) as long as the stories are relevant to the themes listed above.

Submissions MUST be made online using the service Submittable. Visit our website for complete details.

Ice Cube Press is inviting submissions for Fracture: Essays, Poems, and Stories on Fracking in America. We are looking for new prose and poetry that speaks to the complexity of fracking, conveys a sense of place, and includes personal experience.

No fee to submit. Deadline June 1. Visit the publisher's website for guidelines:.

Proximity: A Quarterly Collection of True Stories

For Proximity's sixth issue, editor Towles Kintz is looking for new essays and multimedia (true stories in all forms!) on the theme AT THE TABLE.

"Our world is filled with tables – not just dinner tables or operating tables, but closing tables and sacrament tables, tables covered with flour and yeast, crayons, wood shavings, or blueprints. Send us your most empowering, heartbreaking, celebratory, curious, funny, delicious stories with any table as its centerpiece, and we will rejoice."

Submissions link.

Deadline: January 15, 2015

the museum of americana is happy to announce that we are open to submissions for our Spring issue, which will be a special music-themed issue, from now until January 15th, 2015.

We seek writers who explore and/or repurposes the cultural history of America’s music, especially jazz, country, blues, and rock n’ roll, into fiction, nonfiction, poetry, art, photography, and of course songs. For general guidelines, visit our Submissions page.

Small Po[r]tions is accepting submissions for Issue 4! We publish work that minimizes, blurs, or exaggerates distinctions between genres and hope to offer a shared space for experimental creative fiction and nonfiction, lyrical fiction, poetry, and multimedia pieces. Small Po[r]tions issues have a print component with a focus on book arts and an online component featuring selections from the print issue along with media work. You can view work from our previous issues at our website. Print copies are available on our website as well.

Please submit up to 1000 words or one multimedia work to:

submissionsATsmallportionsjournalDOTcom (Change AT to @ and DOT to . )

by January 18th to be considered for publication in Issue 4.

For additional information, visit our website

or find us on Twitter

or on Facebook

Direct questions to:

editorsATsmallportionsjournalDOTcom (Change AT to @ and DOT to . )

We look forward to reading/viewing your work!

Small Po[r]tions Editorial Board

Arc-24, the literary journal of The Israel Association of Writers in English (IAWE) is open for submission to writing within the theme: Israel.

In 1980 the first editor of our journal, the poet Riva Rubin, named the journal “arc.” Like the deep blue sky arced over the land of Israel, open and encompassing all who live there regardless of religion, politics, gender or age, like the arc of a bridge linking Israel to the English speaking world, arc has been a home to the writers in English who live in Israel.

For arc-24, that policy is changing. We are now open to writers from all over the world, regardless of who you are or where you live so long as the writer has a connection to Israel. The theme of the journal, arc-24 is “Israel.” Entries should fit the topic of Israel, focusing on writing inspired or informed by your personal experiences, observations, and/or cultural and historical events that cover any of the ways Israel has affected you. In your cover letter, please let us know about your connection to Israel.

We welcome submissions of original, unpublished works of poetry, fiction (either short stories or stand alone sections of a longer work), flash fiction, and creative nonfiction to be considered for publication. Surprise us; inspire us. We would especially like to see more short fiction for the journal.

Any work submitted, even if critical of Israel or her policies, should be written in a thoughtful manner. Any pieces submitted which contain hatred or violence will be discarded immediately.

The close date for submissions is January 30, 2015.

· We accept only these file formats for writing: doc, docx, rtf, txt and pdf.

· All submissions should be in font Times New Roman and 11 point.

· All submissions must be made via Submittable, no exceptions.

· We do accept simultaneous submissions. However, kindly drop us a message if your work is accepted elsewhere.

· We seek previously unpublished (including online) work only.

· For poetry, send a selection of 3-5 poems contained within a single document. For fiction and essays please keep to a maximum limit of 6 pages, no more than 1200 words.

· All submission must be received on or before January 30, 2015.

· Payment for publication is one copy of the journal.

The Journal's Non/Fiction Collection Prize

The Ohio State University Press, The OSU MFA Program in Creative Writing, and The Journal are happy to announce that we are now accepting submissions for our annual Non/Fiction Collection Prize (formerly The Short Fiction Prize)! Submit unpublished book-length manuscripts of short prose.

Each year, The Journal selects one manuscript for publication by The Ohio State University Press. In addition to publication under a standard book contract, the winning author receives a cash prize of $1,500.

We will be accepting submissions for the prize from now until February 14th. Further information about the prize is below. Best of luck!

Entries of original prose must be between 150-350 double-spaced pages in 12-point font. All submissions must include a $20.00 nonrefundable handling fee.

Submit an unpublished manuscript of short stories or essays; two or more novellas or novella-length essays; a combination of one or more novellas/novella-length essays and short stories/essays; a combination of stories and essays. Novellas or novella-length nonfiction are only accepted as part of a larger work.

All manuscripts will be judged anonymously. The author's name must not appear anywhere on the manuscript.

Prior publication of your manuscript as a whole in any format (including electronic or self-published) makes it ineligible. Individual stories, novellas or essays that have been previously published may be included in the manuscript, but these must be identified in the acknowledgments page. Translations are not eligible.

Authors may submit more than one manuscript to the competition as long as one manuscript or a portion thereof does not duplicate material submitted in another manuscript and a separate entry fee is paid. If a manuscript is accepted for publication elsewhere, it must be withdrawn from consideration.

The Ohio State University employees, former employees, current OSU MFA students, and those who have been OSU MFA students within the last ten years are not eligible for the award.

See the full guidelines and a list of past winners here.

Submit online through Submittable.

Literature for a Cause anthology

The Literature for a Cause program at the Miami University regional campuses is seeking submissions of provocative literary fiction, creative nonfiction, poetry, and art work for a chapbook anthology focusing on perspectives on mental illness. A portion of the proceeds from the sale of this book will be donated to local nonprofits in the mental health field.

With this anthology, the editors hope to inspire discussion and education in the classroom and among broader audiences about mental illness and its related issues. Specifically, the editors seek compelling creative work that addresses mental illness from a variety of perspectives, including patients, doctors and other professionals, and friends, family, or other witnesses. They are especially interested in work that moves beyond self-expression or the purely inspirational, and that can foster meaningful dialogue by exploring mental illness and related issues from unique or underrepresented angles. Questions driving the creative might include how mental illness is conceptualized and understood, and its impact on ways of thinking, speaking, and interacting in everyday life.

Please submit a cover letter and work in ONE of the following categories:

--Poetry: 3-5 poems, traditional or untraditional, any length, (though shorter is better).

--Art: 3-5 pieces of two-dimensional art, black and white preferred but not required.

--Fiction: one story, double-spaced, 12 point font, 4,000 words maximum.

--Creative nonfiction: one essay, double-spaced, 12 point font, 4,000 word maximum.

The editors prefer unpublished work, but will accept previously published work provided the author owns the rights to the work. Please notify the editors where each piece was originally published in your cover letter.

Email written submissions in a single .doc, .docx, or .rtf attachment, and visual submissions as separate .jpg or .png attachments to:

melbyeeATmiamiohDOTedu (Change AT to @ and DOT to . )

To avoid having your work automatically deleted by an email spam filter, write “L4AC” followed by your last name in the subject line. Deadline for submissions is March 6, 2015.

Writers, use some of your free time this holiday season to give us the gift of reading and considering your work! Prairie Schooner is always on the lookout for poetry, fiction, essays, and reviews. Click here to visit our Submittable page.

The Prairie Schooner blog is currently looking for special submissions on the theme of Women and the Global Imagination to be featured online in January and February. Deadline for submissions is January 15. Click here for more info.

Finally, if you've been working on a fiction or poetry manuscript, get it ready, because the Prairie Schooner Book Prize begins accepting submissions on January 15, 2015. Winners receive $3,000 and publication through the University of Nebraska Press. Click here for all the details.

Deadline: April 13, 2015

For an upcoming issue, Creative Nonfiction is seeking new essays about THE WEATHER. We're not just making idle chit-chat; the weather affects us all, and talking about the weather is a fundamental human experience. Now, as we confront our changing climate, talking about the weather may be more important than ever.

Send us your true stories—personal, historical, reported—about fog, drought, flooding, tornado-chasing, blizzards, hurricanes, hail the size of golfballs, or whatever's happening where you are. We're looking for well-crafted essays that will change the way we see the world around us.

Essays must be vivid and dramatic; they should combine a strong and compelling narrative with an informative or reflective element and reach beyond a strictly personal experience for some universal or deeper meaning. We're looking for well-written prose, rich with detail and a distinctive voice; all essays must tell true stories and be factually accurate.

A note about fact-checking: Essays accepted for publication in Creative Nonfiction undergo a rigorous fact-checking process. To the extent your essay draws on research and/or reportage (and it should, at least to some degree), CNF editors will ask you to send documentation of your sources and to help with the fact-checking process. We do not require that citations be submitted with essays, but you may find it helpful to keep a file of your essay that includes footnotes and/or a bibliography.

Creative Nonfiction editors will award $1,000 for Best Essay and $500 for runner-up. All essays will be considered for publication in a special "Weather" issue of the magazine.

Guidelines: Essays must be previously unpublished and no longer than 4,000 words. There is a $20 reading fee, or $25 to include a 4-issue subscription to Creative Nonfiction (US addresses only). If you're already a subscriber, you may use this option to extend your current subscription or give your new subscription as a gift. Multiple entries are welcome ($20/essay) as are entries from outside the United States (though due to shipping costs we cannot offer the subscription deal). All proceeds will go to prize pools and printing costs.

You may submit essays online or by regular mail:

By regular mail

Postmark deadline April 13, 2015.

Please send manuscript, accompanied by cover letter with complete contact information including the title of the essay and word count; SASE or email for response; and payment to:

Creative Nonfiction

Attn: WEATHER

5501 Walnut Street, Suite 202

Pittsburgh, PA 15232

Online

Deadline to upload files: 11:59 pm EST April 13, 2015

To submit, please go here.

View Next 25 Posts

I had a dear friend who had a gift for telling stories about her day. She’d launch into one, and suddenly everyone around her would hush up and lean in, knowing that whatever followed would be pure entertainment. A story of encountering a deer on the highway would involve interludes from the deer’s point of view. Strangers who factored into her tales would get nicknames and imagined backstories of their own. She could make even the most mundane parts of her day—and everyone else’s—seem interesting. She didn’t aspire to be a writer, but she was a born storyteller.

I had a dear friend who had a gift for telling stories about her day. She’d launch into one, and suddenly everyone around her would hush up and lean in, knowing that whatever followed would be pure entertainment. A story of encountering a deer on the highway would involve interludes from the deer’s point of view. Strangers who factored into her tales would get nicknames and imagined backstories of their own. She could make even the most mundane parts of her day—and everyone else’s—seem interesting. She didn’t aspire to be a writer, but she was a born storyteller.