"You can't wait for inspiration. You have to go after it with a club." -Jack London![]()

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: The Food Network, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 26 - 50 of 91

Blog: TWO WRITING TEACHERS (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: writing, goals, writer's block, graphic organizer, character development, Add a tag

Blog: Utah Children's Writers (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: conflict, character development, agenda, POVs, Add a tag

Everybody has an agenda. We all have desires, hopes, and dreams. We all have principles. We all have goals, whether we formalize them or not. We all have a background and a historical perspective that shapes our actions and our outlook. In our interaction with others, we are at least somewhat aware that the person we are interacting has views and goals that may or may not be the same as ours.

Even the people we love, the people we support, and the people we usually agree with are individuals with their own way of thinking. Every interaction we have is colored by the perspectives and viewpoints of all people involved.

How often have you argued with somebody or watched two people argue when both sides are saying basically the same thing? That happens because we are all individuals and we each have our own agenda, and to some extent, we recognize that our agendas don't always agree, even when the points we are trying to make are the same.

So why should the characters in our stories be any different?

If you want your characters to ring true, they must each have their own world view, their own wants and needs, and their own goals. Their own agendas.

Characters on the same side take that position for their own reasons. Characters on opposite do the same thing. Your protagonist and antagonist might seem like enemies, and since your story is told from the POV of the protagonist (probably), the antagonist may seem evil. But from his point of view, he's probably taking his position as a matter of conscience, because he thinks it's the right thing to do. From the antagonist's point of view, and that of his followers, the protagonist is the bad guy.

But agendas are not limited to main characters. Every time a character appears in our story, even in the most minor of roles, we need to consider what that character wants. Maybe we don't need to create a detailed character analysis of our most minor characters, but we do need to know what each character hopes to achieve. Each character has a life outside the story, even if we don't know anything about it.

Too often, we write a character out of convenience, to fill a story need, without thinking about that character as a real person with hopes and dreams of her own. Usually, when we read and come across a character like that, we're unsatisfied. But still we write them.

Each person in your story world is there for a reason. Not just your reason, to fulfill a story need, but a reason of his or her own. Each character wants something out of his interaction with your other characters or your setting, or whatever he is there for. Even if the character is there solely to offer support to another character, he is offering support for his own, usually selfish, reasons. Even two characters who agree can have agendas that create conflict, and conflict creates story.

So remember that as you write. Every time a character is in a scene, consider why that character is there and what he or she hopes to get out of it. This is one of the most effective ways to turn characters into people.

Blog: A Year of Reading (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: character development, mentor text, Add a tag

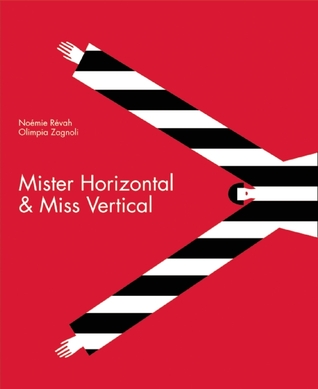

Mister Horizontal & Miss Vertical

by Noémie Révah

illustrations by Olimpia Zagnoli

translated from the French by Claudia Bedrick

Enchanted Lion Books, 2014

review copy provided by the publisher

Mister Horizontal and Miss Vertical couldn't be more different.

Can you guess who likes gliding, boating and "walking in the desert, with sand as far as the eye can see?" And who likes bungee jumping, rockets, and "New York, the city of sky scrapers?"

More than just a concept book about horizontal and vertical, this is a book about opposites, and a fabulous mentor text for writers of all age and experience who need to practice describing their characters in a variety of ways.

Blog: The Children's Book Review (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Fantasy: Supernatural Fiction, Writing Resources, Ages 9-12, Fairy Tales, Chapter Books, Fractured Fairy Tales, Character Development, Jen Calonita, Villians, Add a tag

What makes a villain a villain? I’ve always been a fascinated—and a little bit terrified—of villains, especially in fairytales. As a child, I couldn’t get enough of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs even if the old witch sent me diving into our couch cushions to hide my eyes.

Add a CommentBlog: Adventures in YA Publishing (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Story Structure, Character Development, Craft of Writing, Martina Boone, YA Fiction Giveaways, Add a tag

I turned in my draft of the sequel to Compulsion a couple of weeks ago, and we finally have a name for the book.

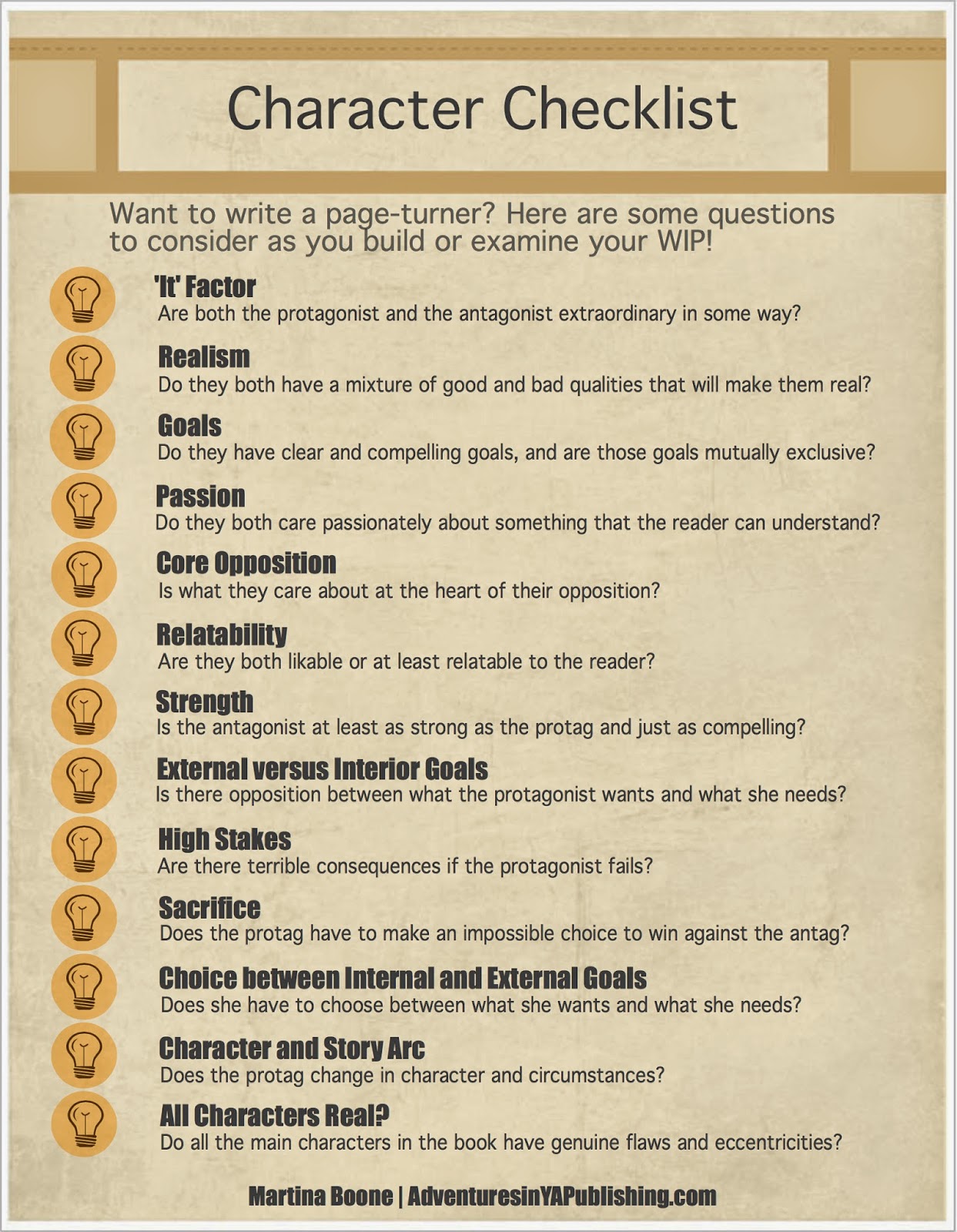

CHARACTER CHECKLIST INFOGRAPHIC

Hexed

Hexedby Michelle Krys

Hardcover

Delacorte Press

Released 6/10/2014

If high school is all about social status, Indigo Blackwood has it made. Sure, her quirky mom owns an occult shop, and a nerd just won’t stop trying to be her friend, but Indie is a popular cheerleader with a football-star boyfriend and a social circle powerful enough to ruin everyone at school. Who wouldn’t want to be her?

Then a guy dies right before her eyes. And the dusty old family Bible her mom is freakishly possessive of is stolen. But it’s when a frustratingly sexy stranger named Bishop enters Indie’s world that she learns her destiny involves a lot more than pom-poms and parties. If she doesn’t get the Bible back, every witch on the planet will die. And that’s seriously bad news for Indie, because according to Bishop, she’s a witch too.

Suddenly forced into a centuries-old war between witches and sorcerers, Indie’s about to uncover the many dark truths about her life—and a future unlike any she ever imagined on top of the cheer pyramid.

Author Question: What is your favorite thing about Hexed?

I love the humor. Indie’s sarcastic commentary and Bishop’s cheeky banter adds some levity to the novel that breaks up some of the heavier, darker paranormal elements of the book.

Purchase Hexed at Amazon

Purchase Hexed at IndieBound

View Hexed on Goodreads

Fill out the Rafflecopter to win, and don't forget to check the sidebar for more great giveaways!

Happy reading and writing, everyone!

Martina

a Rafflecopter giveaway

Blog: Adventures in YA Publishing (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Character Development, Craft of Writing, Martina Boone, Add a tag

Creating a character readers with whom readers connect is tricky. It takes more than creating a heroic or sexy character. It takes more than creating a well-rounded character with quirks and flaws. There are plenty of deep, fascinating characters with whom readers don't connect. Just as we take an instinctive like or dislike to real people, we also engage more with certain protagonists on the page.

|

| Caricature by J.J., SVG file by Gustavb |

- has something she loves.

- has something she fights for.

- is willing to sacrifice for something.

- has some special skill or ability.

- has some handicap or hardship that makes her an underdog.

- has a flaw that readers can relate to and forgive.

- operates from motivation the readers can see and understand.

- has wit, spunk, or a sense of humor.

But that's not the end of the story. Just sprinkling one or two of the above items into a story can make the plot and character feel cardboard and a bit cliche. Most of those "fixes" have been used so often they've led to a whole class of character called a Mary Sue, a figure so romanticized or perfect he or she doesn't come across as believable. Here, by the way, is THE definitive quiz on Mary Sues:

http://www.unc.edu/~jemarti/marysuetest/

Time for tougher questions.

Especially when it comes to the strong female protagonist that so many of us are trying to do justice to lately, how tough is too tough? How much vulnerability do we need to show? How much emotion does a character need to express, and how often? How many hard, confusing, or unlikeable decisions can she make?

As a point of discussion, let's take Katniss Everdeen. There is no question that the whole HUNGER GAMES trilogy is beyond successful, and Katniss is an unforgetable character. But she is one of the recent characters I've seen most often described as "unlikeable." Do you agree? Disagree?

THE HUNGER GAMES is dark and the books get progressively darker. It's tough to be inside that world, and even tougher to be inside Katniss's head. I know for me, I fell in love with Katniss when I saw her willingness to sacrifice for Prim, and she had me hooked with her tenderness to Rue. Her concern for Rue's family, too, made me love her, as did her self-doubt, her willingness to acknowledge and dislike her own questionable motives. I believed in Katniss, hook, line and bow string. In CATCHING FIRE, Katniss was just as real. But Prim was stronger. There was no Rue character. Her situation was much harder, more ambiguous. She was tougher. Did that make her less likeable? I've certainly read that people believe that was the case. What about her depression in MOCKINGJAY? Was that too much?

And here's a better question. Would we be having the same conversation about likeability if Katniss had been a male protagonist?

At the NoVA Teen Book Festival this year, Meagan Spooner mentioned that she got all kinds of hate mail about Lilac, the main female character in THESE BROKEN STARS. That book is wonderful. And Lilac is a terrific character with a huge character ARC. She begins as a spoiled and bitchy rich girl--but even in the darkest early moments of bitchiness, Meagan and her co-author, Amie Kaufman, were careful to lay the foundations that let readers see that there was more going on than met the eye. That was one of the the things that drew me into the book so quickly. Why was Lilac behaving the way she was toward Tarver? Why was she making herself behave that way toward him? Finding out kept me turning pages until I discovered the reason, and by that time, Lilac had already started her transformation into a character I could love.

I can't help wondering if there would have been any complaints at all if the shoe had been on the other foot. Had Tarver been the pampered, beautiful playboy and Lilac the intelligent and hardworking hero, would there have been any hate mail at all? I kind of doubt it, given that that's the cast of the majority of commercial fiction.

I'd love to hear your thoughts. Have you read THESE BROKEN STARS and THE HUNGER GAMES? Would character likeability have been a question at all if the genders of Lilac and Katniss had been reversed?

Blog: Anthony VanArsdale Illustration (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: gryphon warrior, character development, griffin, hero character, Add a tag

Blog: TWO WRITING TEACHERS (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: giveaway, character development, common core, interview, inspiration, Add a tag

Learn about Barry Lane's newest book, Force Field for Good and enter for the giveaway!![]()

Blog: Ingrid's Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Writing Process, Quotes, Quote of the Week, Voice, Character Development, Add a tag

Blog: Ingrid's Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Character Development, Writing Process, Quotes, Quote of the Week, Voice, Add a tag

Blog: TWO WRITING TEACHERS (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: books, character development, mentor texts, Add a tag

Soon-to-be-released The Meaning of Maggie by Megan Jean Sovern is a lovely book that offers plenty of opportunities to study high-level character development. ![]()

Blog: TWO WRITING TEACHERS (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: character development, writing workshop, Add a tag

Are you being your higher self? It's not always easy. Barry Lane and Colleen Mestdagh gave me a lesson in teaching this idea to my students through song, writing and conversation. ![]()

Blog: RabbleBoy (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

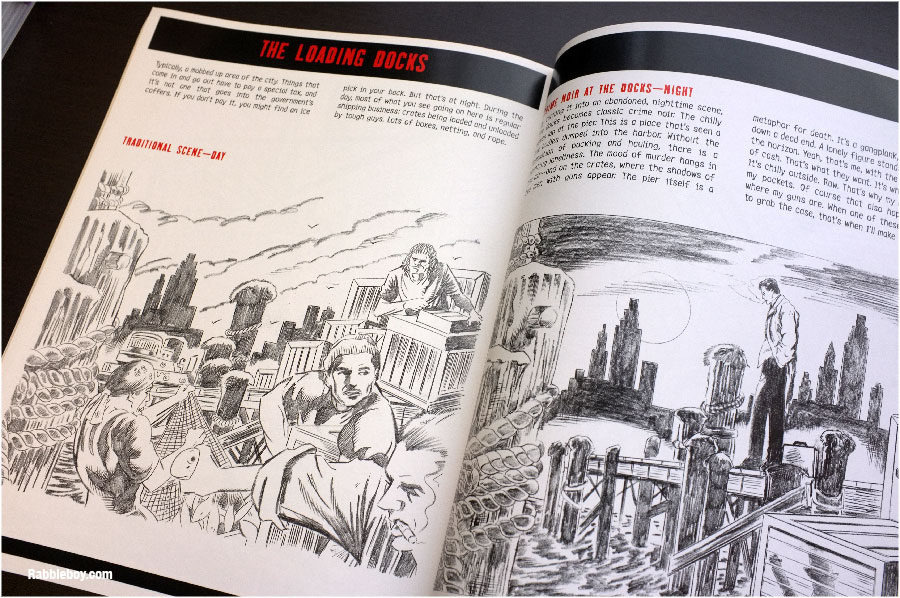

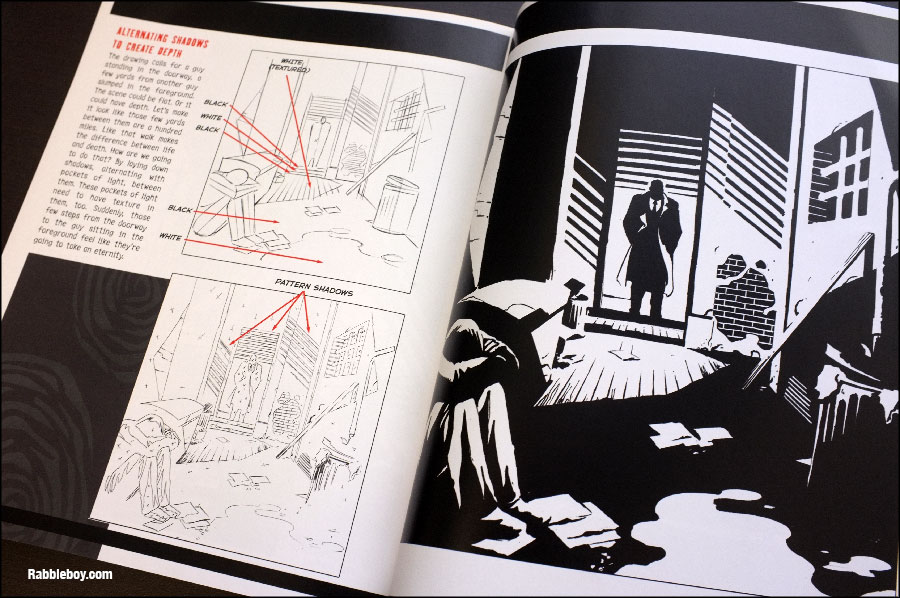

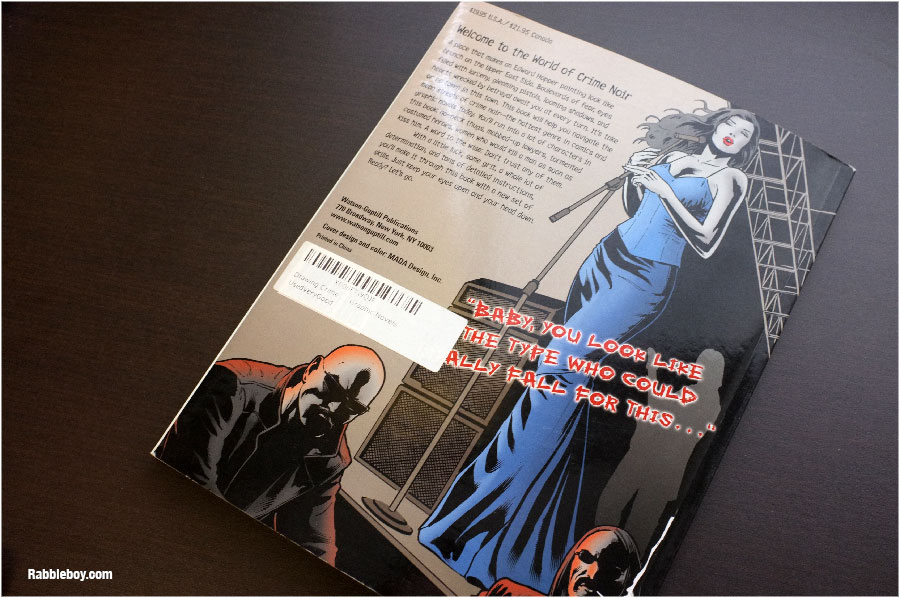

JacketFlap tags: Book Reviews, character design, character development, Frank Miller, Christopher Hart, maltese falcon, Sin City, crime noir, Graphic novel technique, illustrating crime, Illustrating noir style graphic novel, Perspective for graphic novel, Add a tag

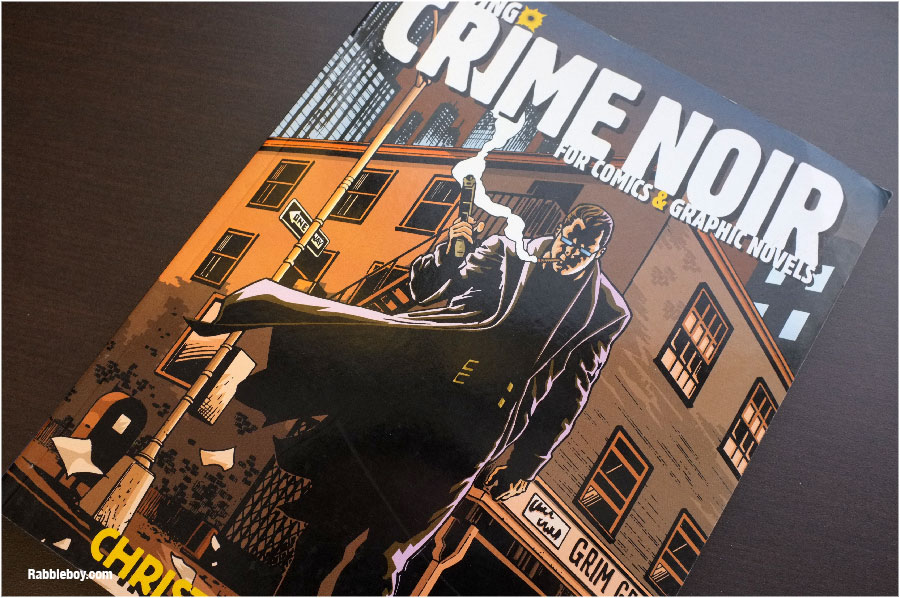

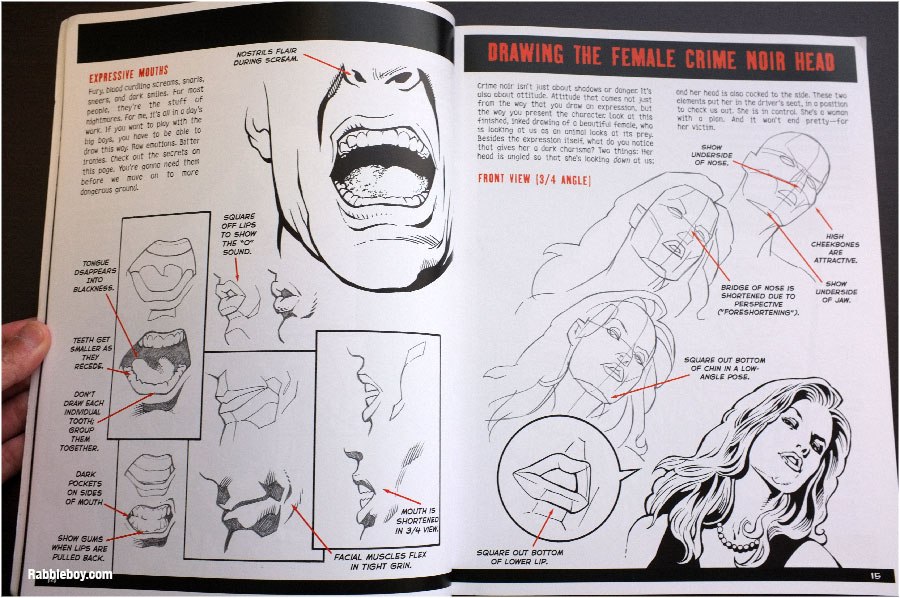

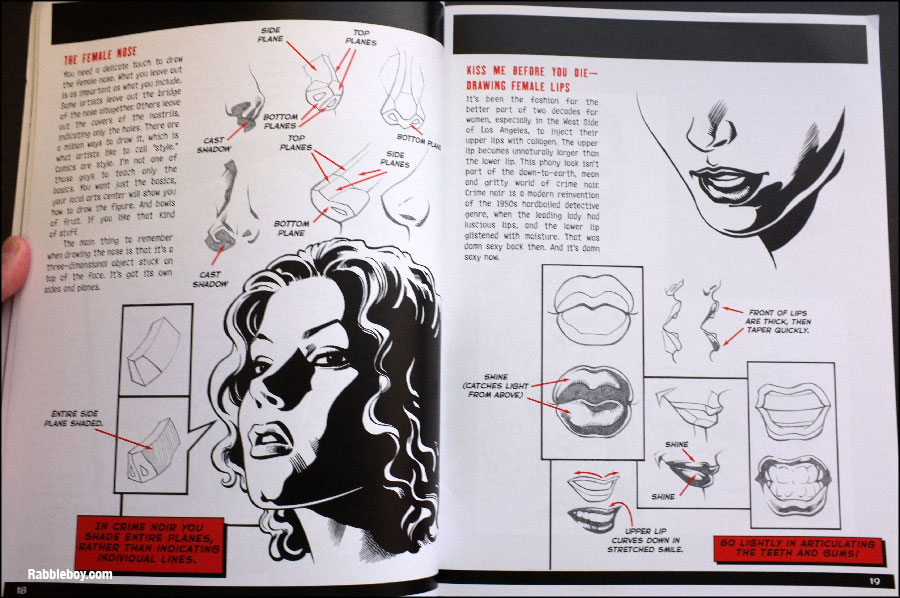

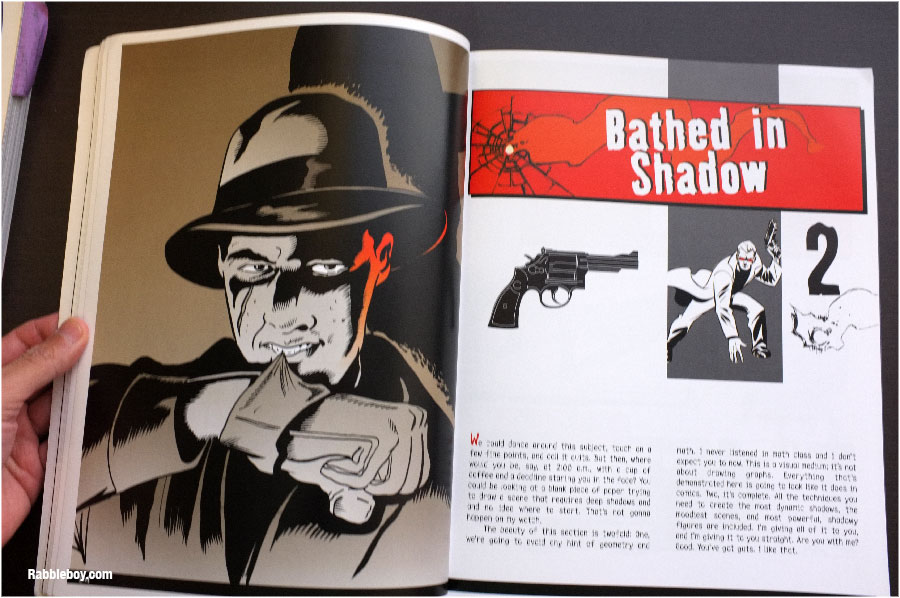

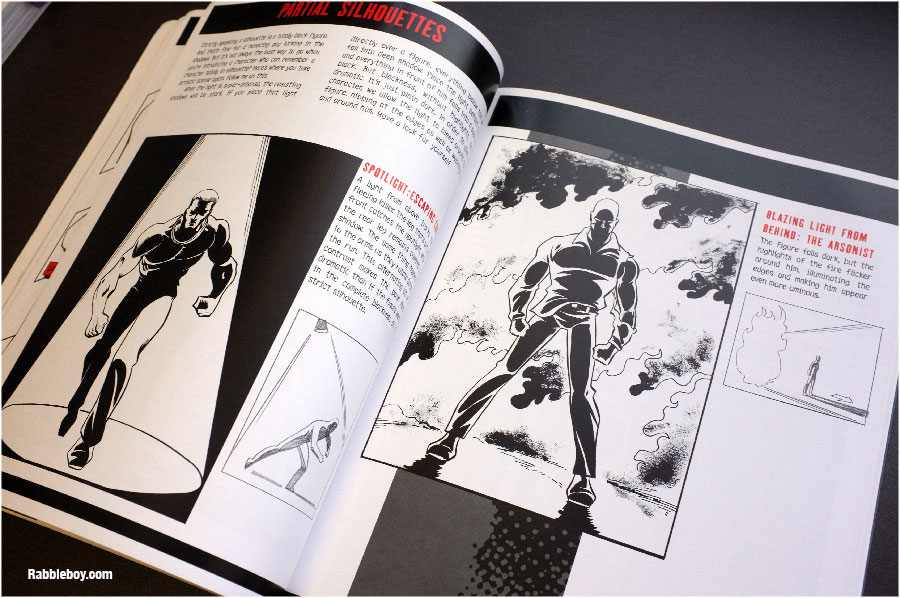

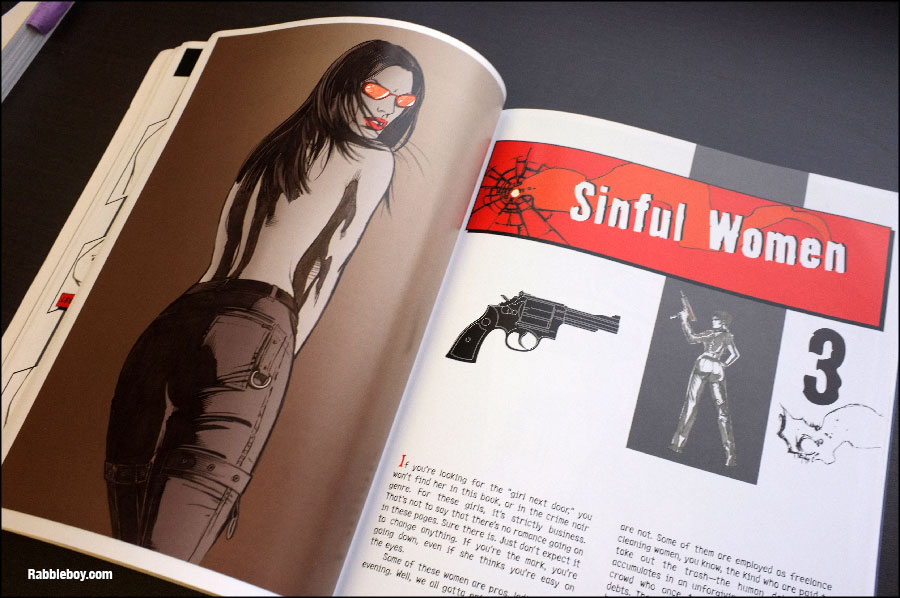

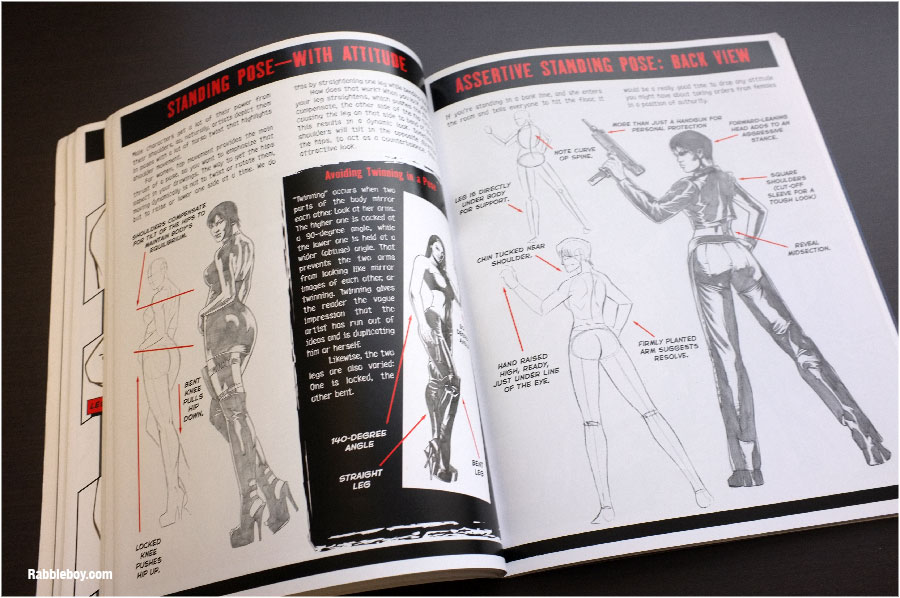

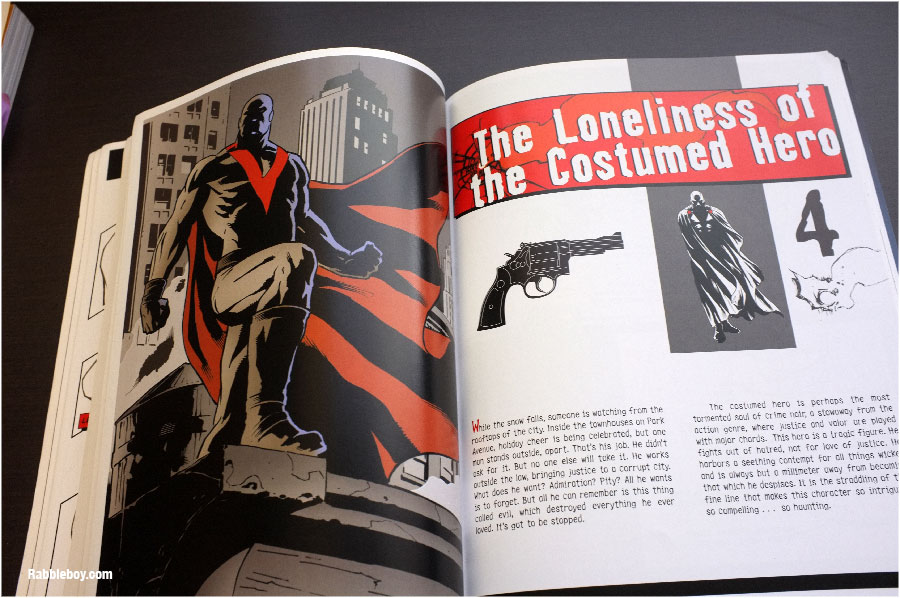

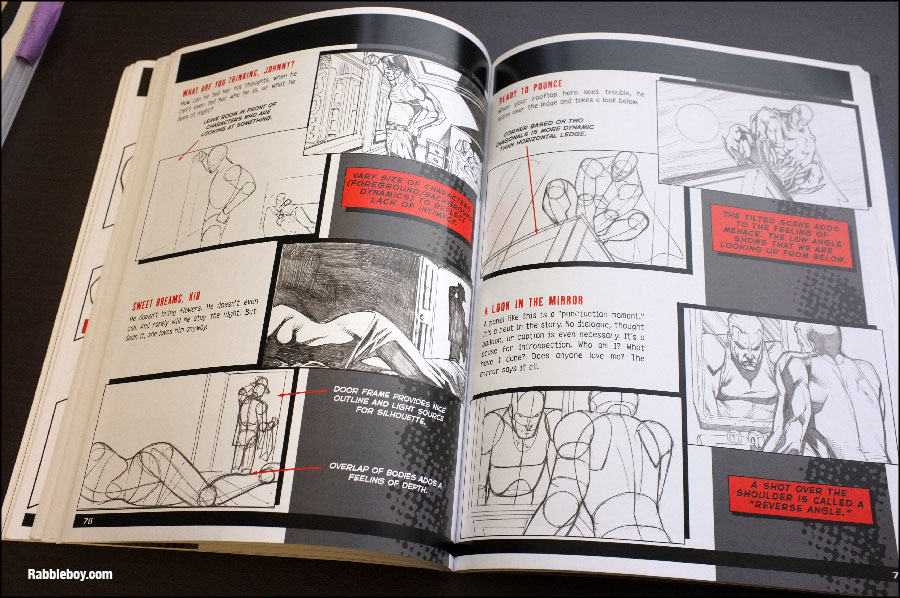

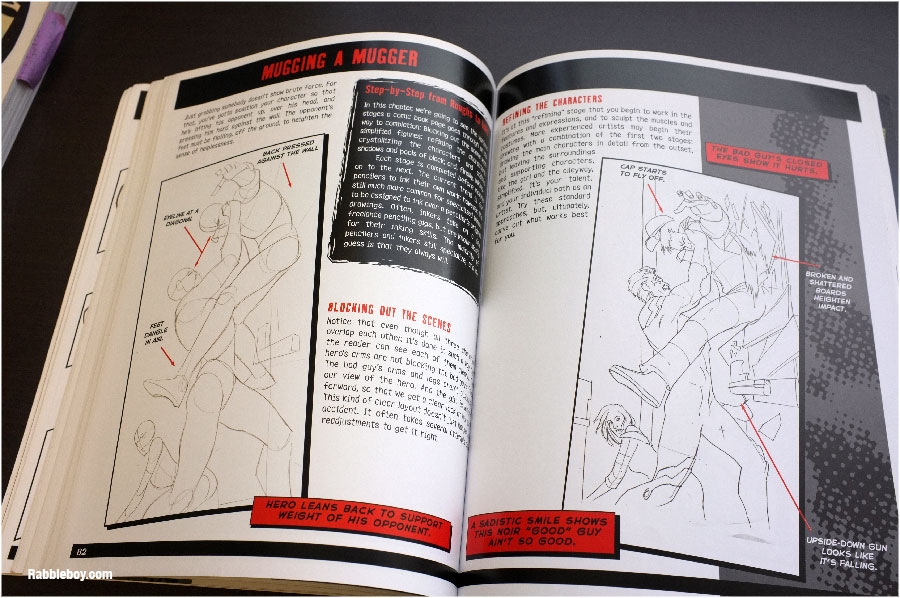

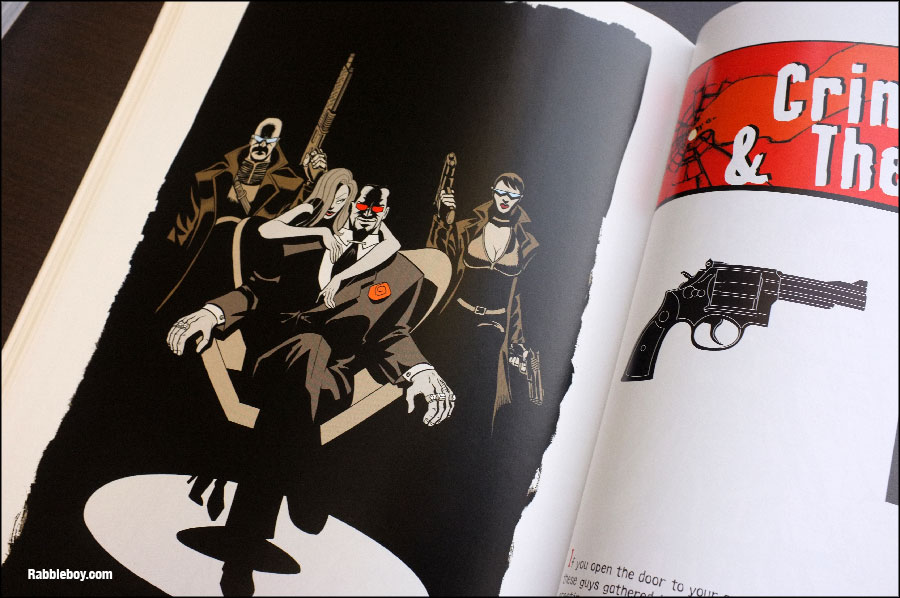

Crime Noir is the most sophisticated, exciting, and dangerous comic book genre around. It is the highly stylized, modern version of such classic 1950s films as “The Maltese Falcon” and “The Asphalt Jungle”. Modern crime noir is exploding in popularity with movies such as “Batman Begins” and graphic novels such as Frank Miller’s “Sin City”. This genre focuses on the mean streets of the city and its amoral characters. Picture windswept streets, deep shadowy figures, reckless woman, men without conscience, reluctant heroes, and boulevards of fear. It’s the desperation of ordinary men, and the loneliness of the action hero. “Drawing Crime Noir” teaches the aspiring artist how to use all of the latest techniques and principles to create the moody world of crime noir. Extensive instruction is offered in the use of shadows to create intense comic book moods and suspense. And there’s more: the costumes of noir – the trench coats and sunglasses of the nihilistic characters: the mobbed-up politicians on the take; and the hit men who keep order; the sexy women who would just as soon kill you as kiss you; techniques for creating dark, brooding, costumed action heroes; and how to turn an ordinary comic book scene into a crime noir scene and how to draw the weapons that the criminals use to make crime pay. Strong, cutting-edge imagery shows artists how to make crime pay. Superstar Christopher Hart explores a new genre. It is perfect for anyone interested in drawing for comic books or graphic

Support Rabbleboy and get this awesome book on Amazon Drawing Crime Noir: For Comics and Graphic Novels

Blog: Ingrid's Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Quotes, Quote of the Week, Character Development, Add a tag

Blog: Ingrid's Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Quotes, Quote of the Week, Character Development, Add a tag

Blog: Ingrid's Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Witches and Children's Literature, Magic, Fairy Tales, Witch, Writing Craft, Evil, Character Development, Witches, Add a tag

By Mary Pleiss

When I was a little girl, the witches I knew came from fairy tales. They were old, ugly, and mean–life ruiners who cast evil spells with no provocation. My young friends and I ran into the problem of the witch in our play. We didn’t want to meet a witch in a dark forest or a bright one, even if that forest was the pair of trees in our backyard. Certainly none of us wanted to be the witch. But we knew we had to have a witch. Witches made things happen, provided scary, shivery tension, and gave the good characters something to fight against and overcome.

When I was a little girl, the witches I knew came from fairy tales. They were old, ugly, and mean–life ruiners who cast evil spells with no provocation. My young friends and I ran into the problem of the witch in our play. We didn’t want to meet a witch in a dark forest or a bright one, even if that forest was the pair of trees in our backyard. Certainly none of us wanted to be the witch. But we knew we had to have a witch. Witches made things happen, provided scary, shivery tension, and gave the good characters something to fight against and overcome.

We often solved this problem by keeping the witch offscreen; we called out plot points detailing the unseen, unheard witch’s actions: “Now the witch is casting her spell. If you get to the swing set, you’re safe!” or, “You stepped into the witch’s clover patch–you’re trapped!” We could imagine the witch without casting her because we’d read stories and seen movies (mostly Disney movies and of course The Wizard of Oz). We knew witches well enough to weave them into our play without having to face the fact that we all had it in ourselves to be witches.

In sixth grade, I read Elizabeth George Speare’s The Witch of Blackbird Pond, and I started thinking about witches in a different way. What made the people of Wethersfield believe Hannah Tupper and Kit Tyler were witches, when any reader could see they weren’t magical or evil–just a little bit different? Why did their neighbors feel the need to banish or imprison them? If Hannah and Kit weren’t really evil, what did that say about the fairy tale witches I’d always feared and hated?

In sixth grade, I read Elizabeth George Speare’s The Witch of Blackbird Pond, and I started thinking about witches in a different way. What made the people of Wethersfield believe Hannah Tupper and Kit Tyler were witches, when any reader could see they weren’t magical or evil–just a little bit different? Why did their neighbors feel the need to banish or imprison them? If Hannah and Kit weren’t really evil, what did that say about the fairy tale witches I’d always feared and hated?

The witches in our fiction today are very different from those in fairy tales, and it turns out that even the Wicked Witch of the West has more complexity than I realized when I was growing up. I knew her from the movie, but reading the books as an adult, and learning more about the history of the Oz books in particular and witches–and those who were accused of witchcraft–in western culture has witches in a new light. L. Frank Baum was heavily influenced by his mother-in-law, Matilda Gage, who was an historian and feminist who promoted influential theories about women who were called witches in history. Baum had those theories in mind when he populated Oz with witches who were more dimensional than what had come before; they had backstories and motivations, and while some of them were evil, just as many were good.

Since Baum, of course, a number of children’s and YA writers have included witches–and women accused of witchcraft–in their stories. Whether bad, good, or somewhere in between, those witches have developed into characters with more depth and complexity than even Baum could have imagined. As societal attitudes about the roles of girls and women have evolved, fictional characterizations of witches have changed, and we can’t get away with taking the problematic witch offscreen or making her a one-dimensional villain. Now, when we write about witches, we work to make them as dimensional as all of our other characters, and our problem becomes the same as that we face with most other characters: how do we bring the witch to life?

Here are some suggestions and questions you can ask yourself if you’re including witchy characters in your fiction:

Consider doing some research into historical witches and witchcraft trials. You might find an angle or a detail no one’s ever written about before.

If your witches really do practice magic, is their power individual or communal, or some combination of both? Is magic learned or innate? Can you make witchcraft/magic a source of conflict, rather than a crutch that relieves it?

Does your character need to make choices about her “witchiness”—whether it’s to become a witch, to fully use or curtail her own power, or to educate herself about her power? Against or for whom she will use her power? Will she embrace her power right away, or resist it?

These are, of course, just a start to creating fully realized witch characters, but they’re a way to turn the witch into an integral part of your story, rather than a flat stereotype. Give your readers more to think about when you write witches, so that kids who play pretend will argue over who gets to be the witch, rather than relegating her to an offscreen ghost.

Mary Pleiss: Though some might say all the hours Mary Pleiss spent haunting the library and disappearing into book worlds hinted at her future in writing for middle grade and young adult readers, she confesses that at the time she just thought it was a good way to escape her noisy family (she loves them, really, but six siblings can be a bit much at times). She is a curriculum development specialist, teacher, and recent graduate of Vermont College of Fine Arts, with an MFA in Writing for Children and Young Adults.

Mary Pleiss: Though some might say all the hours Mary Pleiss spent haunting the library and disappearing into book worlds hinted at her future in writing for middle grade and young adult readers, she confesses that at the time she just thought it was a good way to escape her noisy family (she loves them, really, but six siblings can be a bit much at times). She is a curriculum development specialist, teacher, and recent graduate of Vermont College of Fine Arts, with an MFA in Writing for Children and Young Adults.

Follow Mary on Twitter: @MKPleiss

This blog post was brought to you as part of the March Dystropian Madness blog series.

Blog: Ingrid's Notes (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Witches and Children's Literature, Magic, Fairy Tales, Witch, Writing Craft, Evil, Character Development, Witches, Add a tag

By Mary Pleiss

When I was a little girl, the witches I knew came from fairy tales. They were old, ugly, and mean–life ruiners who cast evil spells with no provocation. My young friends and I ran into the problem of the witch in our play. We didn’t want to meet a witch in a dark forest or a bright one, even if that forest was the pair of trees in our backyard. Certainly none of us wanted to be the witch. But we knew we had to have a witch. Witches made things happen, provided scary, shivery tension, and gave the good characters something to fight against and overcome.

When I was a little girl, the witches I knew came from fairy tales. They were old, ugly, and mean–life ruiners who cast evil spells with no provocation. My young friends and I ran into the problem of the witch in our play. We didn’t want to meet a witch in a dark forest or a bright one, even if that forest was the pair of trees in our backyard. Certainly none of us wanted to be the witch. But we knew we had to have a witch. Witches made things happen, provided scary, shivery tension, and gave the good characters something to fight against and overcome.

We often solved this problem by keeping the witch offscreen; we called out plot points detailing the unseen, unheard witch’s actions: “Now the witch is casting her spell. If you get to the swing set, you’re safe!” or, “You stepped into the witch’s clover patch–you’re trapped!” We could imagine the witch without casting her because we’d read stories and seen movies (mostly Disney movies and of course The Wizard of Oz). We knew witches well enough to weave them into our play without having to face the fact that we all had it in ourselves to be witches.

In sixth grade, I read Elizabeth George Speare’s The Witch of Blackbird Pond, and I started thinking about witches in a different way. What made the people of Wethersfield believe Hannah Tupper and Kit Tyler were witches, when any reader could see they weren’t magical or evil–just a little bit different? Why did their neighbors feel the need to banish or imprison them? If Hannah and Kit weren’t really evil, what did that say about the fairy tale witches I’d always feared and hated?

In sixth grade, I read Elizabeth George Speare’s The Witch of Blackbird Pond, and I started thinking about witches in a different way. What made the people of Wethersfield believe Hannah Tupper and Kit Tyler were witches, when any reader could see they weren’t magical or evil–just a little bit different? Why did their neighbors feel the need to banish or imprison them? If Hannah and Kit weren’t really evil, what did that say about the fairy tale witches I’d always feared and hated?

The witches in our fiction today are very different from those in fairy tales, and it turns out that even the Wicked Witch of the West has more complexity than I realized when I was growing up. I knew her from the movie, but reading the books as an adult, and learning more about the history of the Oz books in particular and witches–and those who were accused of witchcraft–in western culture has witches in a new light. L. Frank Baum was heavily influenced by his mother-in-law, Matilda Gage, who was an historian and feminist who promoted influential theories about women who were called witches in history. Baum had those theories in mind when he populated Oz with witches who were more dimensional than what had come before; they had backstories and motivations, and while some of them were evil, just as many were good.

Since Baum, of course, a number of children’s and YA writers have included witches–and women accused of witchcraft–in their stories. Whether bad, good, or somewhere in between, those witches have developed into characters with more depth and complexity than even Baum could have imagined. As societal attitudes about the roles of girls and women have evolved, fictional characterizations of witches have changed, and we can’t get away with taking the problematic witch offscreen or making her a one-dimensional villain. Now, when we write about witches, we work to make them as dimensional as all of our other characters, and our problem becomes the same as that we face with most other characters: how do we bring the witch to life?

Here are some suggestions and questions you can ask yourself if you’re including witchy characters in your fiction:

Consider doing some research into historical witches and witchcraft trials. You might find an angle or a detail no one’s ever written about before.

If your witches really do practice magic, is their power individual or communal, or some combination of both? Is magic learned or innate? Can you make witchcraft/magic a source of conflict, rather than a crutch that relieves it?

Does your character need to make choices about her “witchiness”—whether it’s to become a witch, to fully use or curtail her own power, or to educate herself about her power? Against or for whom she will use her power? Will she embrace her power right away, or resist it?

These are, of course, just a start to creating fully realized witch characters, but they’re a way to turn the witch into an integral part of your story, rather than a flat stereotype. Give your readers more to think about when you write witches, so that kids who play pretend will argue over who gets to be the witch, rather than relegating her to an offscreen ghost.

Mary Pleiss: Though some might say all the hours Mary Pleiss spent haunting the library and disappearing into book worlds hinted at her future in writing for middle grade and young adult readers, she confesses that at the time she just thought it was a good way to escape her noisy family (she loves them, really, but six siblings can be a bit much at times). She is a curriculum development specialist, teacher, and recent graduate of Vermont College of Fine Arts, with an MFA in Writing for Children and Young Adults.

Mary Pleiss: Though some might say all the hours Mary Pleiss spent haunting the library and disappearing into book worlds hinted at her future in writing for middle grade and young adult readers, she confesses that at the time she just thought it was a good way to escape her noisy family (she loves them, really, but six siblings can be a bit much at times). She is a curriculum development specialist, teacher, and recent graduate of Vermont College of Fine Arts, with an MFA in Writing for Children and Young Adults.

Follow Mary on Twitter: @MKPleiss

This blog post was brought to you as part of the March Dystropian Madness blog series.

Blog: WOW! Women on Writing Blog (The Muffin) (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: character, character development, LuAnn Schindler, timeline of events, using a timeline, Add a tag

I've been reworking (okay, heavy editing and restructuring) of a book I've been working on for what seems like 10 years. (It's actually been that long. I'm a perfectionist. Sigh.) While reading, I noticed several elements seemed contradictory, especially when talking about time. A couple details seemed out of place, like the order was jumbled, causing confusion in the storyline.

It reminded me why, when I taught composition and even creative writing to high school students, I would use a timeline handout, like the one in the photo. In order for a story to be consistent, discrepancies in time (or setting or character growth) cannot be present.

Here's how it works:

- Make a timeline of events from the time period. I'm not talking within the story, I'm talking about a timeline of what was happening in the world during the time period include in your piece. When I wrote a one-act play for my students to perform for competition this year, which was based on 9/11, I wanted to include the number one song in the U.S., and within each vignette, I planned to feature a bit of pop culture. I made a timeline for how the events of that day unfolded and researched pop culture tidbits. It added a great sense of place to the plot.

- Make a timeline for a character. How does a specific character get from point A to point B? It doesn't matter if you're talking about specific movement, the timeline can show events that cause a change in personality or a moment that leads to character growth.

- Start plotting. I like to mesh the two timelines together and create a scene. It's a handy tool that shows where pacing needs to increase, action needs a jolt of energy, and characters need a healthy dose of conflict to create a stronger story.

Have you used a timeline to help define your storyline?

by LuAnn Schindler. Read more of her work at her website.

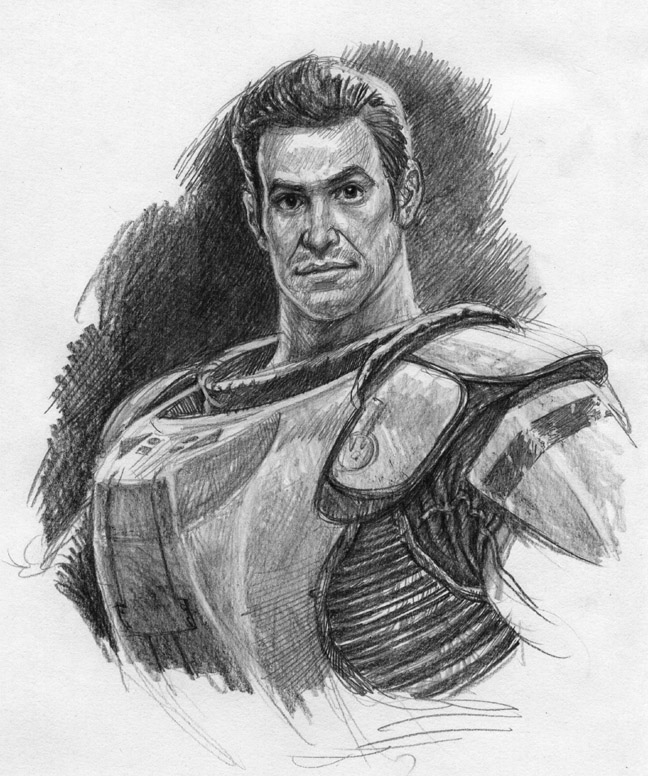

Blog: Anthony VanArsdale Illustration (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: character development, Add a tag

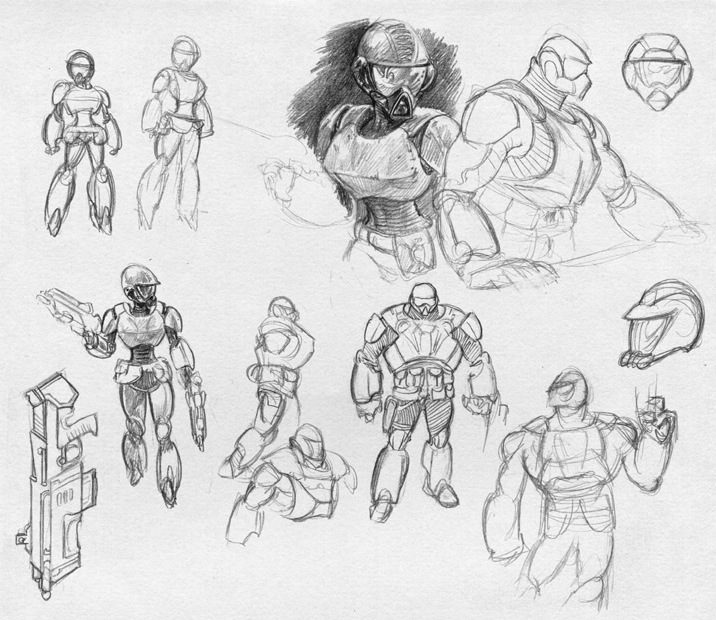

Here are a few character sketches for some generic heroes I'll be building (low polly) in the 3d program Blender. I've been playing with it the last few weeks and I've made some progress in the sculpting department. Still need a better grasp on rigging and some of the detail aspects of UV mapping.

Blog: Utah Children's Writers (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: character development, Writing, characters, Add a tag

By Julie Daines

Blog: WOW! Women on Writing Blog (The Muffin) (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: characterization, dream, character development, Elizabeth King Humphrey, Add a tag

|

| Would your character walk alone on a beach on a foggy day? Or is your character one who needs to be surrounded by friends on a sunny day? Either communicates your character to your reader. Credit: Flickr | kke227 |

Alongside a cast of various colleagues, a deceased superstar also made his appearance.

To say the least, it was very strange and I relayed the dream to a friend who knows the players, minus the superstar.

I expressed to her how believable and realistic it was as I gave her a rundown of the music that was playing and named these actors. I described what some of the people were doing and we laughed about how characteristic it was for Craig to refuse to participate in the dance that was taking place. In my dream, Craig would physically turn away from the others. As he does in real life. Another friend, Sue, insisted on organizing the merry band of my dream actors. She would wave her arms, as if trying to circulate the air, in an attempt to motivate these people. Trudy sat waiting for directions from others and would only participate if coaxed by another. Trudy stared at her hands in her lap, rarely glancing at others. (The names of these friends have been changed. It's the least I can do when they end up in my dreams!)

Finally, I can explain why I feel this dream felt so important to my writing. Just as with writing, you want to bring depth to your characters. But you also want to signal to your reader--often through small actions, personality traits that have an impact on the other actors. Craig, Sue, and Trudy provided that. It is those actions (or something similar) I may use for one of my characters.

The specific actions or certain behaviors of these real folks had crystallized in my dream. The dream, even as extravagant as it was, seeped realism to me because these simple actions or reactions. I couldn't see all their movements or hear what they were saying, but they communicated a lot of their personality through these small, repeated actions. And this dream will probably inform my future writing. What about your dreams?

When you are writing your story, what small action details do you add and subtly repeat to communicate a larger picture to your reader? And, out of curiosity, have you ever had a celebrity appear in your dreams? If so, who?

Elizabeth King Humphrey writes and edits, when she is not having strange dreams. She lives in coastal North Carolina.

Blog: Utah Children's Writers (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: character, character development, Add a tag

By Julie Daines

I've been reading several stories lately with struggling characters. And by struggling, I mean characters that are inconsistent and hard to believe.

If you are struggling to make your characters come across as real, believable, and engaging to readers, here is a little piece of advice that might help.

Establish what each character's motives are. What is the one thing that that character wants, and why? Once you figure that out, everything a character does should be to achieve that goal. Even if the choices they make aren't always the smartest, in the character's mind they should be to achieve that one, all important goal. This will keep your character consistent and believable.

Your main character's objective should be obvious to the reader in the first chapter.

Example: The Hunger Games

What one goal of Katniss's drives the story forward and is at the root of nearly everything she does? Her desire to protect her sister, Prim. She volunteers to go to the games in place of Prim, and she wants to win not just to survive, but so she can be there for Prim.

Example: The Forest of Hands and Teeth

What is it that Mary longs for? To see the ocean, and thus have a connection with her mother. This is what drives Mary out when the walls are breached and keeps her going. In my opinion, this comes across as a selfish motive, but at least it is consistent. And let's face it, teens often have selfish motives.

Example: The Lord of the Rings

What objective does Frodo have in his heart that keeps him going on his impossible quest? The Shire. He wants to get back home to the Shire, and he wants the Shire to be safe and uncorrupted by Sauron.

You have to find your character's Shire.

Blog: Utah Children's Writers (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Writing, characters, three, character development, taffy lovell, Add a tag

One of the hardest things to write is good characters, all of them. How many times have you read a book and only one or two or three characters have any life to them? The rest are just...there?

Do you have trouble filling out your characters?

Have you tried the Power of Three for your characters?

Try these ideas on ALL your characters:

Three wishes

Three fears

Three flaws

Three heroic qualities

Here are ones I did for my MC, Angelica:

Three wishes:

To be a normal girl

For her dad to not have to work so much

Get her sister out of an abusive relationship

Three fears:

She really is a serial killer

She will lose her family

She is a monster

Three flaws:

Set herself up to be unlovable so no one else dies

Distrustful

Chooses to be a wallflower

Three heroic qualities:

Loyal

Brave

Smart

Now your turn.

Choose one category and share with us in comments!

Or if that is too hard, tell us your favorite character.

Blog: Utah Children's Writers (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: character development, Richard Peck, facing bad experiences, writing difficult characters, Add a tag

Think about the experience you would have avoided if you could. We all have things in our lives that fit this description. What emotion is connected to that experience? What would you have done to avoid it if we had known it was coming? Who would you be now, if that experience had not existed in your life?

Blog: TWO WRITING TEACHERS (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: pop culture, character development, Add a tag

My husband and I spent ten hours watching “The Newsroom” this summer. We DVRed all of the episodes so we could watch them at our leisure. By episode four I was hooked by… Read More ![]()

View Next 25 Posts

Okay. I’m convicted now. I keep falling into the “I want this to sound beautiful” trap, rather than really examining how my character would describe her world. I’m not being honest about the character or with myself. So, thanks for this timely quote.