new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: german, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 25 of 30

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: german in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Lizzie Furey,

on 10/19/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

gothic,

Oxford Etymologist,

church,

German,

blessing,

word origins,

curse,

Greek,

etymology,

anatoly liberman,

Linguistics,

Anglo-Saxon,

cursing,

*Featured,

Word Origins And How We Know Them,

The Oxford Etymologist,

Old Enlgish,

Add a tag

Curse is a much more complicated concept than blessing, because there are numerous ways to wish someone bad luck. Oral tradition (“folklore”) has retained countless examples of imprecations. Someone might want a neighbor’s cow to stop giving milk or another neighbor’s wife to become barren.

The post Blessing and cursing part 2: curse appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Lizzie Furey,

on 9/7/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

language,

words,

Oxford Etymologist,

German,

word origins,

english,

House,

dwelling,

booth,

Linguistics,

Bauer,

*Featured,

shieling,

Add a tag

This post has been written in response to a query from our correspondent. An answer would have taken up the entire space of my next “gleanings,” and I decided not to wait a whole month.

The post Our habitat: booth appeared first on OUPblog.

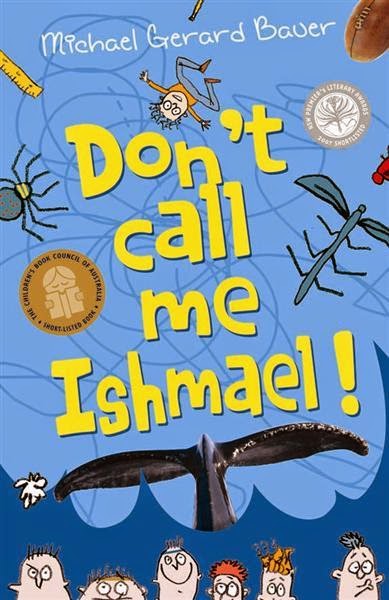

Don't Call Me IshmaelMichael Gerard Bauer

MG/YA

If the cold, dreary, dark days of January have blanketed you, this is just the right read.

Don't Call Me Ishmael is

Bud, not Buddy hilarious and set in Australia, where, currently, it is summer! So pull up a chair and toast your toes on the warmth and humor of this story.

Basic plot: Ishmael Leseur, a Year Nine student (that's down under for ninth grader), suffers from ILS, Ishmael Leseur Syndrome, which is Ishmael's name for his particular brand of adolescent/early teeanage agony. It's made up of a "crawl in a hole" embarrassing story why he parents named him after one of literature's most renowned protagonists, a bully who teases him about said name, a girl whom he is crazy for but who doesn't know he exists, and a group of misfit friends who are constantly getting themselves into embarrassment squared messes.

I discovered this book in, of all things, German (although the author is from and story set in Australia, so no worries, you can easily get it in English). My husband comes from ye olde country and we've raised our daughters bi-lingually, which has meant a lot of audiobooks "auf Deutsch". I chose this title for its length. Shameful, I know, but it was six hours long instead of the meager two so many middle grade German audible books come in at. So there you have it, random parameters (barrage young ears with as much second language as possible) unearthed a humor goldmine.

I wish I could say I know how Bauer does it, but I don't, which is why I've gotten the other two books in this series to get behind his humor trick. He is spot on with adolescent funny. My daughters and I laugh out loud in the car on the way to school every morning. Me, maybe more. The agony of teenagerdom maybe hits a little too close to home for barrel laughs for them. Theirs is more the "somebody else is going through this?!?" ha-ha-whew.

So there you have it. Pick up a copy of

Don't Call Me Ishmael and start 2015 off with a good laugh and an uproarious story. For more cheer in these bleak months, check out the reviews on

Barrie Summy's website (and pray that groundhog doesn't see his shadow!)

By: Sara Pinotti,

on 10/19/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Language,

old,

German,

english,

Dutch,

Linguistics,

Scandinavian,

Latin,

necromancy,

reconstruction,

*Featured,

linguistic,

george walkden,

linguistic necromancy: a guide for the uninitiated,

proto,

Add a tag

It’s fairly common knowledge that languages, like people, have families. English, for instance, is a member of the Germanic family, with sister languages including Dutch, German, and the Scandinavian languages. Germanic, in turn, is a branch of a larger family, Indo-European, whose other members include the Romance languages (French, Italian, Spanish, and more), Russian, Greek, and Persian.

Being part of a family of course means that you share a common ancestor. For the Romance languages, that mother language is Latin; with the spread and then fall of the Roman empire, Latin split into a number of distinct daughter languages. But what did the Germanic mother language look like? Here there’s a problem, because, although we know that language must have existed, we don’t have any direct record of it.

The earliest Old English written texts date from the 7th century AD, and the earliest Germanic text of any length is a 4th-century translation of the Bible into Gothic, a now-extinct Germanic language. Though impressively old, this text still dates from long after the breakup of the Germanic mother language into its daughters.

How does one go about recovering the features of a language that is dead and gone, and which has left no records of itself in spoken or written form? This is the subject matter of linguistic necromancy – or linguistic reconstruction, as it is more conventionally known.

The enterprise, dubbed “darkest of the dark arts” and “the only means to conjure up the ghosts of vanished centuries” in the epigraph to a chapter of Campbell’s historical linguistics textbook, really got off the ground in the 1900s due to a development of a toolkit of techniques known as the comparative method.

Crucial to the comparative method was a revolutionary empirical finding: the regularity of sound change. Though it has wide-reaching implications, the basic finding is simple to grasp. In a nutshell: it’s sounds that change, not words, and when they change, all words which include those sounds are affected.

Let’s take an example. Lots of English words beginning with a p sound have a German counterpart that begins with pf. Here are some of them:

- English path: German Pfad

- English pepper: German Pfeffer

- English pipe: German Pfeife

- English pan: German Pfanne

- English post: German Pfoste

If the forms of words simply changed at random, these systematic correspondences would be a miraculous coincidence. However, in the light of the regularity of sound change they make perfect sense. Specifically, at some point in the early history of German, the language sounded a lot more like (Old) English. But then the sound p underwent a change to pf at the beginning of words, and all words starting with p were affected.

There’s much more to be said about the regularity of sound change, since it underlies pretty much everything we know about language family groupings. (If you’re interested in finding out more, Guy Deutscher’s book The Unfolding of Language provides an accessible summary.) But for now let’s concentrate on its implications for necromantic purposes, which are immense.

If we want to invoke the words and sounds of a long-dead language like the mother language Proto-Germanic (the ‘proto-’ indicates that the language is reconstructed, rather than directly evidenced in texts), we just need to figure out what changes have happened to the sounds of the daughter languages, and to peel them back one by one like the layers of an onion. Eventually we’ll reach a point where all the daughter languages sound the same; and voilà, we’ve conjured up a proto-language.

There’s more to living languages than just sounds and words though. Living languages have syntax: a structure, a skeleton. By contrast, reconstructed protolanguages tend to look more like ghosts: hauntingly amorphous clouds of words and sounds. There are practical reasons why the reconstruction of proto-syntax has lagged behind. One is simply that our understanding of syntax, in general, has come a long way since the work of the reconstruction pioneers in the 19th century.

Another is that there is nothing quite like the regularity of syntactic change in syntax: how can we tell which syntactic structures correspond to each other across languages? These problems have led some to be sceptical about the possibility of syntactic reconstruction, or at any rate about its fruitfulness. Nevertheless, progress is being made. To take one example, English is a language that doesn’t like to leave out the subject of a sentence. We say “He speaks Swahili” or “It is raining”, not “Speaks Swahili” or “Is raining”. Though most of the modern Germanic languages behave the same, many other languages, like Italian and Japanese, have no such requirement; speakers can include or omit the subject of the sentence as the fancy takes them. Was Proto-Germanic like English, or like Italian or Japanese, in this respect? Doing a bit of necromancy based on the earliest Germanic written records suggests that Proto-Germanic was, like the latter, quite happy to omit the subject, at least under certain circumstances.Of course the issue is more complex than that – Italian and Japanese themselves differ with regard to the circumstances under which subjects can be omitted.

Slowly but surely, though, historical linguists are starting to add skeletons to the reanimated spectres of proto-languages.

The post Linguistic necromancy: a guide for the uninitiated appeared first on OUPblog.

An Order of Amelie, Hold the Fries Nina Schindler, translated from the German by Rob Barrett

An Order of Amelie, Hold the Fries Nina Schindler, translated from the German by Rob Barrett

You gotta love a book that references Leonard Cohen on the second page. With a big ol' picture of him, too.

Tim's a student who sees the woman of his dreams. He doesn't know her, but her address falls out of her bag, so he takes a risk and emails her. Only... it wasn't her email address. Amelie is NOT the girl of Tim's dreams, but her reply charms him, so he writes back and writes back, until she caves. It's a very sweet relationship the develops as Amelia tries to figure out what to do about her new feelings for Tim and some negative feelings with her very serious long-distance boyfriend.

Format wise, this one's much closer to Middle School is Worse than Meatloaf as we get a much better visual on the notes, flowers that are also sent, phones used in text messages (you actually tell the who's texting who because their phones are different.)

Interestingly, even though this is a German book, it takes place in Canada.

It's a short, sweet read that's a great use of the stuff format.

Book Provided by... my wallet

Links to Amazon are an affiliate link. You can help support Biblio File by purchasing any item (not just the one linked to!) through these links. Read my full disclosure statement.

By:

Melissa Wiley,

on 9/10/2012

Blog:

Here in the Bonny Glen

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Links,

author interviews,

Foreign Languages,

German,

Japanese,

Language Arts,

Assorted and Sundry,

Brave Writer,

Into the Thicklebit,

Add a tag

New Thicklebit: Tats for Tots.

New interview: Writing on the Sidewalk.

Foreign language app we are finding irresistible, with a deliciously mockable edge: Earworms. (I learned about it at GeekMom. Rose and Beanie are using the German; Jane, the Japanese. Rose likes it so much she ponied up her own funds for the Arabic.)

Other resources Jane is using to learn Japanese (answering Ellie‘s question from my learning notes blog): Pimsleur Approach audio program (check your library for these); Free Japanese Lessons; Learn Japanese Adventure (another free site).

I had such a fun time yesterday recording a Brave Writer podcast with Julie Bogart and her son. I’ll let you know when it goes live! The Prairie Thief is the October selection for Brave Writer’s Arrow program—a monthly digital language arts curriculum featuring a different work of fiction in each installment. Brave Writer is one of the first resources I ever gushed about on this blog, way back in 2005.  And as you’ll discover in the podcast, Julie Bogart was the blogger who inspired me to start Bonny Glen in the first place!

And as you’ll discover in the podcast, Julie Bogart was the blogger who inspired me to start Bonny Glen in the first place!

By: Alice,

on 2/15/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Oxford Etymologist,

German,

word origins,

english,

Pushkin,

Hebrew,

etymology,

anatoly liberman,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

balderdash,

The Tale of the Priest and His Workman Balda,

balda,

balder,

Add a tag

By Anatoly Liberman

Unlike hogwash or, for example, flapdoodle, the noun balderdash is a word of “uncertain” (some authorities even say of “unknown”) origin. However, what is “known” about it is probably sufficient for questioning the disparaging epithets. We can dismiss with a condescending smile all kinds of imaginative rubbish (balderdash?) proposed by those who believed that knowing one or two old languages is enough for discovering an etymology, but one such guess is curious. According to it, the English noun goes back to Hebrew Bal, allegedly contracted from Babel, and dabar. The “curiosity” consists in the fact that there is a German verb (aus)baldowern “to nose out a secret or some information” (aus- is a prefix), from the language of the underworld. It goes back to Yiddish, ultimately Hebrew, ba’al-dabar “the lord of the word or of the thing” (ba’al has nothing to do with Babel). Thus, a fanciful etymology suggested for one word in English fits a German word of similar structure.

An equally ingenious attempt to supply balderdash with divine ancestry takes us all the way to the north. Engl. jovial, from French, from Italian, from Latin, was coined with the sense “under the influence of the planet Jupiter” (which astrologists regarded as the source of happiness”; compare by Jove!). The name of the most beautiful Scandinavian god was Baldr, Anglicized as Balder. Inspired by those facts, a resourceful author wrote in 1826: “The vilest of prose and poetry is called balder-dash; now Balder was among the Scandinavians the presiding god of poetry and eloquence.” Poor Baldr (who, incidentally, had nothing to do with poetry and eloquence)! As though it was not enough to be murdered at the Assembly with the mistletoe… He also had to bear the responsibility for enriching the English language with the word balderdash, which surfaced only at the end of the sixteenth century, millennia after the heinous deed.

As often in such cases, it remains unclear whether the word under discussion is native or borrowed. Not surprisingly, Spanish baldon(e)ar “to insult” and Welsh baldorddus “tattling” have been cited as possible etymons of balderdash. The trouble with Celtic words is that, even when the connection looks good, we cannot always ascertain the direction of borrowing (for example, from English to Welsh or from Welsh to English?). The history of English etymology is full of the Celtomaniacs who traced hundreds of words to Irish Gaelic, and of passionate deniers, who refused to believe that any Celtic language had the power to influence English. Besides, as one should never tire of repeating, it is not enough to point to a similar-sounding word in a foreign language without reconstructing the path of penetration. When and in what circumstances could a Spanish verb become so popular in England that English speakers adopted it as their slang (and a noun into the bargain)?

Pushkin’s Balda watching the old devil’s grandson who is trying to carry a mare after Balda easily “carried” it between his legs (that is, simply rode it).

The Hebrew etymology of

balderdash is, of course, a bad joke, but it brings out the fact that in several languages words designating various undignified concepts begin with

bal(d)-. In Dutch we see

baldadig “wanton” (an adjective formed from the noun meaning “evil

The Helpful Elves by August Kopish, one of many classic children's book reprints given a fresh existence by the splendid Floris Books

'Based on a well-known poem by Kopisch (1799-1853) and illustrated in muted tones by Braun-Fock (1898-1973), the charm of this tale lies in the tiny elf tabs found at the top of each page. Together in a row, 10 elves are perched expectantly -- each made distinct with a different smile or a long white beard -- forming a miniature audience to watch readers. One can almost hear them gleefully giggling at the comeuppance they know is coming at the end. An enchanting, if abrupt, piece of German lore brought to a new audience. The lesson, curiosity killed the cat, rings true in all cultures.' -- KIRKUS

By:

admin,

on 10/31/2011

Blog:

Litland.com Reviews!

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

World War II,

wild west,

England,

classroom,

German,

Christian,

children's lit,

character education,

guns,

Vicar,

book club,

country,

west,

Britain,

Catholic,

virtue,

advanced reader interest,

Summer/vacation reading,

teachers/librarians,

character formation,

unwed mother,

homeschooling,

juvenile,

stamps,

tween,

teen,

primary,

United Kingdom,

Oliver Twist,

pregnancy,

horse,

justice,

road show,

parent,

prisoner,

morals,

reader,

teach,

orphan,

secondary,

review,

mysteries,

reading,

photos,

kids,

teaching,

ya,

teens,

children's books,

book reviews,

books,

family,

Uncategorized,

courage,

generosity,

friendship,

adventure,

book,

young adult,

ethics,

WWII,

book review,

Adults,

children's,

historical fiction,

art,

Mystery,

character,

woods,

cowboy,

homeschool,

Brit,

Add a tag

Bradley, Alan. (2010) The Weed That Strings the Hangman’s Bag. (The Flavia de Luce Series) Bantam, division of Random House. ISBN 978-0385343459. Litland recommends ages 14-100!

Publisher’s description: Flavia de Luce, a dangerously smart eleven-year-old with a passion for chemistry and a genius for solving murders, thinks that her days of crime-solving in the bucolic English hamlet of Bishop’s Lacey are over—until beloved puppeteer Rupert Porson has his own strings sizzled in an unfortunate rendezvous with electricity. But who’d do such a thing, and why? Does the madwoman who lives in Gibbet Wood know more than she’s letting on? What about Porson’s charming but erratic assistant? All clues point toward a suspicious death years earlier and a case the local constables can’t solve—without Flavia’s help. But in getting so close to who’s secretly pulling the strings of this dance of death, has our precocious heroine finally gotten in way over her head? (Bantam Books)

Our thoughts:

Flavia De Luce is back and in full force! Still precocious. Still brilliant. Still holding an unfortunate fascination with poisons…

As with the first book of the series, The Sweetness at the Bottom of the Pie, we begin with a seemingly urgent, if not sheer emergency, situation that once again turns out to be Flavia’s form of play. We also see the depth of her sister’s cruelty as they emotionally badger their little sister, and Flavia’s immediate plan for the most cruel of poisoned deaths as revenge. Readers will find themselves chuckling throughout the book!

And while the family does not present the best of role models (smile), our little heroine does demonstrate good character here and there as she progresses through this adventure. As explained in my first review on this series, the protagonist may be 11 but that doesn’t mean the book was written for 11-year olds :>) For readers who are parents, however (myself included), we shudder to wonder what might have happened if we had bought that chemistry kit for our own kids!

Alas, the story has much more to it than mere chemistry. The author’s writing style is incredibly rich and entertaining, with too many amusing moments to even give example of here. From page 1 the reader is engaged and intrigued, and our imagination is easily transported into the 1950’s Post WWII England village. In this edition of the series, we have more perspective of Flavia as filled in by what the neighbors know and think of her. Quite the manipulative character as she flits around Bishop’s Lacy on her mother’s old bike, Flavia may think she goes unnoticed but begins to learn not all are fooled…

The interesting treatment of perceptions around German prisoners of war from WWII add historical perspective, and Flavia’s critical view of villagers, such as the Vicar’s mean wife and their sad relationship, fill in character profiles with deep colors. Coupled with her attention to detail that helps her unveil the little white lies told by antagonists, not a word is wasted in this story.

I admit to being enviou

By: Lauren,

on 5/25/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

correct spelling,

english spelling,

first consonant shift,

odd spelling,

th sound,

the letter h,

theta,

“tea”,

Reference,

Oxford Etymologist,

Dictionaries,

German,

word origins,

etymology,

anatoly liberman,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

Add a tag

By Anatoly Liberman

Because of the frequency of the words the, this, that, these, those, them, their, there, then, and with, the letter h probably occurs in our texts more often than any other (for Shakespeare’s epoch thee and thou should have been added). But then of course we have think, three, though, through, thousand, and words with ch, sh, ph, and gh. Despite the prominence of h in written English its status is entirely undeserved, because it performs its most important historical task, namely to designate the sound in words like have, hire, home, and so forth only in word and morpheme initial position (the latter as in rehire, dehydrated, and the like).

The history of h is dramatic. Germanic experienced a change known as the First Consonant Shift (a big shock, as the capitalization above shows). When we compare Latin quod “what” (pronounced kwod) and its Old English cognate hwæt (the same meaning; pronounced with the vowel of Modern Engl. at), we see that Engl. h corresponds to Latin k. A series of such regular correspondences separates Germanic from its non-Germanic Indo-European “relatives,” and this is what the shift is all about. The k ~ h pair is only one of nearly a dozen. When the shifted k arose more than two thousand year ago, it had the sound value of ch in Scots loch, but then the weakening of Germanic consonants set in (linguists call this process lenition), and the guttural sound was one of its casualties: it stopped being guttural and became “mere breath,” as we now have in home and hell. Degraded to breath, or aspiration, h began to disappear. In no other Germanic language has the habit of dropping one’s h’s advanced as far as in English, but it can be observed in all its modern and medieval neighbors, especially in popular speech. For example, in the delightful Middle Dutch narrative poem about the arch-scoundrel Reineke Fox (the French call the beast Reynard) h is dropped on a scale unthinkable in Modern Dutch. Standard English frowns upon h-less words, but in a few cases they managed to assert themselves. For instance, the form preceding modern them was hem, and that is why we say tell’em: it is not th that has been shed, but h. However, what the sound h has lost in pronunciation, the letter h has more than regained on paper.

Each case—the introduction of ch, sh, and gh—deserves a special essay, but I will devote this post only to th. Today th designates a voiceless consonant (as in cloth) and a voiced one (as in clothe). Both sounds existed in Old English, though their occurrence and distribution were partly different from what we find in the modern language, and there were special letters for them—þ (voiceless) and ð (voiced). They go back to the form of two ancient runes. But from early on the Romance tradition became dominant in Germanic scriptoriums: in German, Dutch, and English we find the digraphs (that is, two-letter groups) dh and th. Dh did not stay anywhere, but th did and is ambiguous, for, at least theoretically, it could be used f

By: Lauren,

on 5/18/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

essex,

Oxford Etymologist,

Dictionaries,

German,

word origins,

onomatopoeia,

dictionary,

etymology,

anatoly liberman,

Scandinavian,

norwegian,

word history,

*Featured,

Lexicography & Language,

larrup,

lunker,

you big lunk,

lunker,

Add a tag

(The first word was larrup.)

By Anatoly Liberman

Lunker seems to be well-known in the United States and very little in British English. Mark Twain used lunkhead “blockhead.” Lunker surfaced in books later, but lunkhead must have been preceded by lunk, whatever it meant. In today’s American English, lunker has several unappetizing and gross connotations, and we will let them be: one cannot constantly deal with turd and genitals. Only two senses bear upon etymological discussion: “a very big object” and “big game fish.” From the meager facts at my disposal I am apt to conclude that “big fish” is secondary, so that the word hardly arose in the lingo of fishermen. Also, lunkhead probably alluded to someone with a big head “typical of an idiot,” as they used to say.

In dictionaries I was able to find only one conjecture on the origin of lunker. The Random House Unabridged Dictionary (RHD) suggested that it might be a blend of lump and hunk. Unless we know for certain that a word is a blend (cf. smog, brunch, motel, blog, gliberal, Eurasia, Tolstoevsky, and the like), it is impossible to prove that some lexical unit is the product of merger: for instance, squirm is perhaps a blend of squirt and worm but perhaps not. I suspect that RHD’s idea was suggested by The Century Dictionary, which, although it offers no derivation of lunkhead and does not list lunker, refers under lummox “an unwieldy, clumsy, stupid fellow” (“probably ultimately connected with lump”) to British dialectal lummakin “heavy; awkward.” Lump turned up first only in Middle English. It has numerous cognates in Dutch, German, and the Scandinavian languages and seems to have developed from the basic meaning “a shapeless mass.” No impassable barrier separates lunk- from lump-, for n and m constantly alternate in roots, and final -p and -k are also good partners (see the previous post). German Lumpen means “rag,” and a rag may be understood as a shapeless mass or something hanging loose. It is the semantics that complicates our search for the etymology of lunker: we need cognates that mean “a big thing,” and they refuse to appear. Lump does provide a clue to the history of lunker; by contrast, hump may be left out of the picture: we have enough trouble without it.

Joseph Wright included lunkered (not lunker!) in The English Dialect Dictionary, but without specifying his sources or saying, as he often did: “Not known to our informants.” His definition is curt: “(of hair) tangled; Lincolnshire.” He also cited several other similar northern (English and Scots) words, of which especially instructive are lunk “heave up and down (as a ship); walk with a quick uneven, rolling motion; limp” and lunkie “a hole left for the admission of animals.” Unlike larrup, discussed in the previous post, lunker did find its way into my database. A single citation occurs in The Essex Review for 1936. The Reverend W. J. Pressey quotes a 1622 entry in a diary: “Absent from Church, and for ‘lunkering’ a poor woman’s house in great Sampford, to the great fear and terror of the said poor woman.” He comments:

“This word is derived from the Scandinavian. ‘Lunkere

By: Lauren,

on 3/2/2011

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Food and Drink,

language,

beer,

Oxford Etymologist,

German,

alcohol,

word origins,

Greek,

etymology,

vodka,

arabic,

anatoly liberman,

drinking,

Scandinavian,

word history,

ale,

*Featured,

notes and queries,

Lexicography & Language,

black and tan,

hittite,

Add a tag

By Anatoly Liberman

The surprising thing about the runic alu (on which see the last January post), the probable etymon of ale, is its shortness. The protoform was a bit longer and had t after u, but the missing part contributed nothing to the word’s meaning. To show how unpredictable the name of a drink may be (before we get back to ale), I’ll quote a passage from Ralph Thomas’s letter to Notes and Queries for 1897 (Series 8, volume XII, p. 506). It is about the word fives, as in a pint of fives, which means “…‘four ale’ and ‘six ale’ mixed, that is, ale at fourpence a quart and sixpence a quart. Here is another: ‘Black and tan.’ This is stout and mild mixed. Again, ‘A glass of mother-in-law’ is old ale and bitter mixed.” Think of an etymologist who will try to decipher this gibberish in two thousand years! We are puzzled even a hundred years later.

Prior to becoming a drink endowed with religious significance, ale was presumably just a beverage, and its name must have been transparent to those who called it alu, but we observe it in wonder. On the other hand, some seemingly clear names of alcoholic drinks may also pose problems. Thus, Russian vodka, which originally designated a medicinal concoction of several herbs, consists of vod-, the diminutive suffix k, and the feminine ending a. Vod- means “water,” but vodka cannot be understood as “little water”! The ingenious conjectures on the development of this word, including an attempt to dissociate vodka from voda “water,” will not delay us here. The example only shows that some of the more obvious words belonging to the semantic sphere of ale may at times turn into stumbling blocks. More about the same subject next week.

Hypotheses on the etymology of ale go in several directions. According to one, ale is related to Greek aluein “to wander, to be distraught.” The Greek root alu- can be seen in hallucination, which came to English from Latin. The suggested connection looks tenuous, and one expects a Germanic cognate of such a widespread Germanic word. Also, it does not seem that intoxicating beverages are ever named for the deleterious effect they make. A similar etymology refers ale to a Hittite noun alwanzatar “witchcraft, magic, spell,” which in turn can be akin to Greek aluein. More likely, however, ale did not get its name in a religious context, and I would like to refer to the law I have formulated for myself: a word of obscure etymology should never be used to elucidate another obscure word. Hittite is an ancient Indo-European language once spoken in Asia Minor. It has been dead for millennia. Some Hittite and Germanic words are related, but alwanzatar is a technical term of unknown origin and thus should be left out of consideration in the present context. The most often cited etymology (it can be found in many dictionaries) ties ale to Latin alumen “alum,” with the root of both being allegedly alu- “bitter.” Apart from some serious phonetic difficulties this reconstruction entails, here too we would prefer to find related forms closer to home (though Latin-Germanic correspondences are much more numerous than those between Germanic and Hittite), and once again we face an opaque technical term, this time in Latin.

Equally far-fetched are the attempts to connect ale with Greek alke “defence” and Old Germanic alhs “temple.” The first connection might work if alke were not Greek. I am sorry

By: Emily Smith Pearce,

on 2/1/2011

Blog:

Emily Smith Pearce

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

children's literature,

Culture,

caricature,

cartoon,

Germany,

children's book,

German,

Inspirations,

Museum,

Lisbeth Zwerger,

expatriate,

Hannover,

max and Moritz,

Wilhelm Busch,

author,

Illustration,

Ronald Searle,

Art,

Add a tag

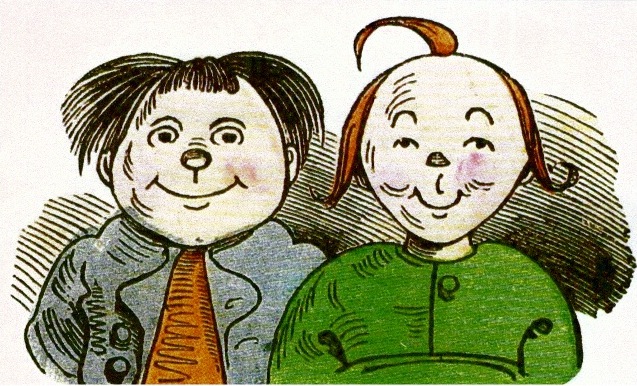

You know the Brothers Grimm, but maybe you haven’t heard of some other famous German brothers: Max and Moritz. They’re some of the most beloved characters in all of German literature.

Published in 1865, Max and Moritz is the story of two naughty brothers whose adventures range from mischievous to vicious. Their darkly comical story is told in a series of seven pranks, and in the end….well, let’s just say they don’t get away with their crimes. It’s not exactly a Disney fairy tale.

The subversive humor of the book and the boys’ flippancy toward adults represented a departure in the children’s literature of the time, which was strictly moralistic.

The book’s action-filled sequential line drawings are paired with relatively little text. It’s widely believed that Max and Moritz was the direct inspiration for the Katzenjammer Kids, the ”oldest American comic strip still in syndication and the longest-running ever.” (from Wikipedia)

The other day I made a date with myself to go to the Wilhelm Busch Museum here in Hannover. The creator of Max and Moritz, illustrator and poet Wilhelm Busch, lived in and around Hannover for several years of his life. The museum is located on the edge of the royal Herrenhauser Gartens. It’s my favorite kind of museum: small, intimate, a beautiful space with really strong exhibits. It houses some of the original Max and Moritz sketches—I love seeing the rough beginnings of things.

Here’s the museum below:

The museum also hosts temporary exhibits of illustration and caricature, and I was lucky enough to catch the show of Lisbeth Zwerger, famed Austrian illustrator. I’ve been a fan of her whimsical fairy tale illustrations for a long time, so it was really interesting to see them in person. Along with German and English editions of Max and Moritz, I couldn’t resist getting Zwerger’s Noah’s Ark, also in the original German—I guess it’ll be good for my language skills.

Also on display, and equally interesting, was a large retrospective show of influential British carticature artist Ronald Searle. I snapped a quick pic of this machine in the corner of the gallery:

What do you think it is? I’m guessing it’s a hygrometer to make sure the air doesn’t get too damp and damage the artwork, but I don’t know.

I can’t wait to get back to the museum for the next exhibits.

The Max and Moritz image above, which is in the public domain, was found at wikipedia. Information in this post com

The Princess Trap Kirsten Boie trans. David Henry Wilson

The Princess Trap Kirsten Boie trans. David Henry Wilson

I loved loved loved The Princess Plot and almost fell over in glee when I saw that there was a sequel! Because there didn't have to be one. There just is one.

After saving Scandia from a coup, Jenna and her mother are back in the royal family, but Jenna's not adjusting to life in the public eye very well. From being raised in a very over-protected sheltered home to having every move monitored by the paparazzi... ugh. To top it off, the girls are her exclusive boarding school are mean mean mean and particularly pick on the physical characteristics that show that Jenna's father was of Northern descent.

But when she runs away, she ends up running straight into the arms of old enemies who are once again plotting to rule Scandia.

Lots of intrigue and the reader is lucky enough to get every side to this story. The focus shifts quickly between all the different players. I loved how the ruling classes were engineering everything because they didn't want to give up any of their wealth and prestige to the North Scandians.

I also love that when the focus shifts so that we get every side, I mean every side-- we get to see what the adults are doing, too. I KNOW! Adults as valid characters in a children's* book! WHO WHUDDA THUNK?! Although, I could have done with some more Ylva. I needed to see some more of her to fully buy the ending.

This book-- both the story and the way it's told-- is more complex than things we usually see for tweens but I think that's awesome because I know tweens can handle it. I just love that Boie gives them the chance and that Chicken House gave it a chance to have it translated and brought over. I hope to see more of Boie's work in English (because I can't read German and am probably never going to learn how.)

I'm kinda pissed at the SLJ review of the original that says the plot is "often confusing." Just because not everything's spoon-fed to us it's confusing? The only problem with getting every side is that in the first book, the reader often knew what was going on waaaaaaaaaay before the characters did. While that's true in this book as well, there's enough action to in between when the characters are trying to figure out the evil plot that it's actually kinda helpful that the reader already knows what's up and I really didn't mind it at all (and that's something I usually mind!)

*This seems to be one of those books that some libraries have in J, some in YA. We have it in J, but we have a pretty high J/YA break. I think it's good for 5-8th grade-- perfect tween level.

Book Provided by... my local library

Links to Amazon are an affiliate link. You can help support Biblio File by purchasing any item (not just the one linked to!) through these links.

0 Comments on The Princess Trap as of 1/1/1900

The machine in the corner probably provides a record of humidity and temperature levels in the building.

GD Bob