By Stephen Foster

Finishing a book is a burden lifted accompanied by a sense of loss. At least it is for some. Academic authors, stalked by the REF in Britain and assorted performance metrics in the United States, have little time these days for either emotion. For emeriti, however, there is still a moment for reflecting upon the newly completed work in context—what were it origins, what might it contribute, how does it fit in? The answer to this last query for an historian of colonial America with a collateral interest in Britain of the same period is “oddly.” Somehow the renascence of interest in the British Empire has managed to coincide with a decline in commitment in the American academy to the history of Great Britain itself. The paradox is more apparent than real, but dissolving it simply uncovers further paradoxes nested within each other like so many homunculi.

Begin with the obvious. If Britain is no longer the jumping off point for American history, then at least its Empire retains a residual interest thanks to a supra-national framework, (mostly inadvertent) multiculturalism, and numerous instances of (white) men behaving badly. The Imperial tail can wag the metropolitan dog. But why this loss of centrality in the first place? The answer is also supposed to be obvious. Dramatic changes, actual and projected, in the racial composition of late twentieth and early twenty-first century America require that greater attention be paid to the pasts of non-European cultures. Members of such cultures have in fact been in North America all along, particularly the indigenous populations of North America at the time of European colonization and the African populations transported there to do the heavy work of “settlement.” Both are underrepresented in the traditional narratives. There are glaring imbalances to be redressed and old debts to be settled retroactively. More Africa, therefore, more “indigeneity,” less “East Coast history,” less things British or European generally.

The all but official explanation has its merits, but as it now stands it has no good account of how exactly the respective changes in public consciousness and academic specialization are correlated. Mexico and people of Mexican origin, for example, certainly enjoy a heightened salience in the United States, but it rarely gets beyond what in the nineteenth century would have been called The Mexican Question (illegal immigration, drug wars, bilingualism). Far more people in America can identify David Cameron or Tony Blair than Enrique Peña Nieto or even Vincente Fox. As for the heroic period of modern Mexican history, its Revolution, it was far better known in the youth of the author of this blog (born 1942), when it was still within living memory, than it is at present. That conception was partial and romantic, just as the popular notion of the American Revolution was and is, but at least there was then a misconception to correct and an existing interest to build upon.

One could make very similar points about the lack of any great efflorescence in the study of the Indian Subcontinent or the stagnation of interest in Southeast Asia after the end of the Vietnam War despite the increasing visibility of individuals from both regions in contemporary America. Perhaps the greatest incongruity of all, however, is the state of historiography for the period when British and American history come closest to overlapping. In the public mind Gloriana still reigns: the exhibitions, fixed and traveling, on the four hundredth anniversary of the death of Elizabeth I drew large audiences, and Henry VIII (unlike Richard III or Macbeth) is one play of Shakespeare’s that will not be staged with a contemporary America setting. The colonies of early modern Britain are another matter. In recent years whole issues of the leading journal in the field of early American history have appeared without any articles that focus on the British mainland colonies, and one number on a transnational theme carries no article on either the mainland or a British colony other than Canada in the nineteenth century. Although no one cares to admit it, there is a growing cacophony in early American historiography over what is comprehended by early and American and, for that matter, history. The present dispensation (or lack thereof) in such areas as American Indian history and the history of slavery has seen real and on more than one occasion remarkable gains. These have come, however, at a cost. Early Americanists no longer have a coherent sense of what they should be talking about or—a matter of equal or greater significance–whom they should be addressing.

Historians need not be the purveyors of usable pasts to customers preoccupied with very narrow slices of the present. But for reasons of principle and prudence alike they are in no position to entirely ignore the predilections and preconceptions of educated publics who are not quite so educated as they would like them to be. In the world’s most perfect university an increase in interest in, say, Latin America would not have to be accompanied by a decrease in the study of European countries except in so far as they once possessed an India or a Haiti. In the current reality of rationed resources this ideal has to be tempered with a dose of “either/or,” considered compromises in which some portion of the past the general public holds dear gives way to what is not so well explored as it needs to be. Instead, there seems instead to be an implicit, unexamined indifference to an existing public that knows something, is eager to know more, and, therefore, can learn to know better. Should this situation continue, outside an ever more introverted Academy the variegated publics of the future may well have no past at all.

Stephen Foster is Distinguished Research Professor Emeritus (History), Northern Illinois University. His most recent publication is the edited volume British North America in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries (2013).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

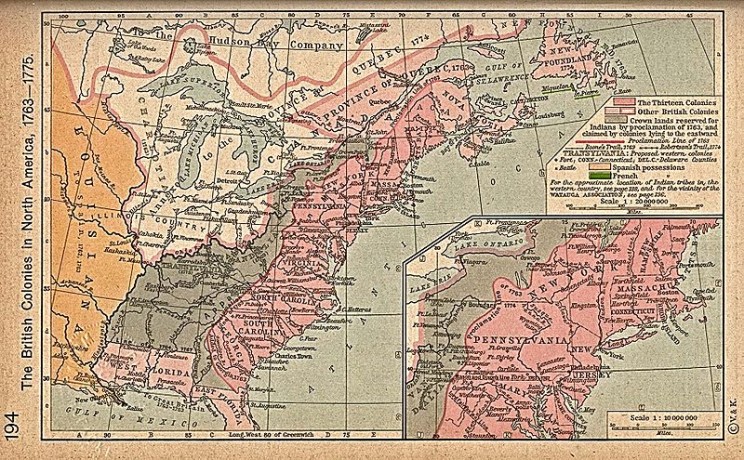

Image credit: The British Colonies 1763 to 1776. By William R. Shepherd, 1923. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Declaration of independence appeared first on OUPblog.