By Anatoly Liberman

A Happy New Year to our readers and correspondents! Questions, comments, and friendly corrections have been a source of inspiration to this blog throughout 2012, as they have been since its inception. Quite a few posts appeared in response to the questions I received through OUP and privately (by email). As before, the most exciting themes have been smut and spelling. If I wanted to become truly popular, I should have stayed with sex, formerly unprintable words, and the tough-through-though gang. But being of a serious disposition, I resist the lures of popularity. It is enough for me to see that, when I open the page “Oxford Etymologist,” the top post invites the user to ponder the origin of fart. And indeed, several of my “friends and acquaintance” (see the previous gleanings) have told me that they enjoy my blog, but invariably added: “I have read your post on fart. Very funny.” I remember that after dozens of newspapers reprinted the fart essay, I promised a continuation on shit. Perhaps I will keep my promise in 2013. But other ever-green questions also warm the cockles of my heart, especially in winter. For instance, I never tire of answering why flammable means the same as inflammable. Why really? And now to business.

Folk etymology. “How much of the popular knowledge of language depends on folk etymology?” I think the question should be narrowed down to: “How often do popular ideas of language depend on folk etymology?” People are fond of offering seemingly obvious explanations of word origins. Sometimes their ideas change a well-established word. Shamefaced, to give just one example, developed from shame-fast (as though restrained by shame). Some mistakes are so pervasive that one day the wrong forms may share the fate of shame-fast. Such is, for example, protruberance, by association with protrude. Despite what the OED says, it seems more probable that miniscule developed from minuscule only because the names of mini-things begin with mini-. Incidentally, from a historical point of view, even miniature has nothing to do with the picture’s small size. Most people would probably say that massacre has the root mass- (“mass killing”), but the two words are not connected. Anyone can expand this list.

Sound symbolism. A correspondent has read my book on word origins and came across a section on words beginning with gr-, such as Grendel and grim. Since they often refer to terror and cruelty (at best they designate gruff and grouchy people), he wonders how the word grace belongs here. It does not. Sound symbolism is a real force in language. One can cite any number of words with initial gl- for things glistening and gleaming, with fl- when flying, flitting, and flowing are meant, as well as unpleasant sl-words like slimy and sleazy. But green, flannel, and slogan will show that at best we have a limited tendency rather than a rule. Besides, many sound symbolic associations are language-specific. So somebody who has a daughter called Grace need not worry.

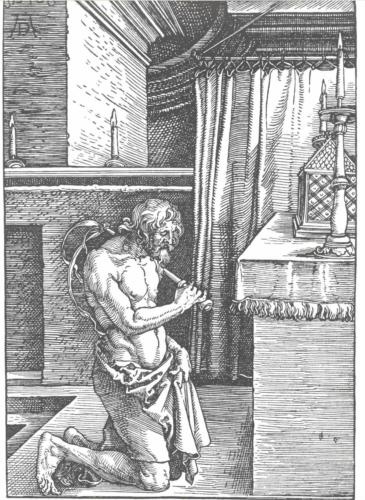

Grendel attacking Three Graces.

Engl. galoot and Catalan golut. More than four years ago, I wrote a triumphant post on the origin of Engl. galoot. The reason for triumph was that I was the first to discover the word’s derivation (a memorable event in the life of an etymologist). Just this month one of our correspondents discovered that post and asked about its possible connection with Catalan golut “glutton; wolverine.” This, I am sure, is a coincidence. In the Romance languages, we find words representing two shapes of the same root, namely gl- and gl- with a vowel between g and l. They inherited this situation from Latin: compare gluttire “to swallow” and gola “throat.” English borrowed from Old French and later from Latin several words representing both forms of the root, as seen in glut ~ glutton and gullet. As for the sense “wolverine” (the name of a proverbially voracious animal, Gulo luscus), it has also been recorded in English. By contrast, Engl. galoot has not been derived from the gl- root, with or without a vowel in the middle. It goes back to Dutch, while the Dutch took it over from Italian galeot(t)o “sailor” (which is akin to galley).

Judgement versus judgment. This is an old chestnut. Both spellings have been around for a long time. Acknowledgment and abridgment belong with judgment. Since the inner form of all those word is unambiguous, the variants without e cause no trouble. The widespread opinion that judgment is American, while judgement is British should be repeated with some caution, because the “American” spelling was at one time well-known in the UK. However, it is true that modern American editors and spellcheckers require the e-less variant. I would prefer (though my preference is of absolutely no importance in this case) judgement, that is, judge + ment. The deletion of e produces an extra rule, and we have enough of silly spelling rules already. Another confusing case with -dg- is the names Dodgson and Hodgson. Those bearers of the two names whom I knew pronounced them Dodson and Hodson respectively, but, strangely, many dictionaries give only the variant with -dge-. Is it known how Lewis Carroll, the author of Alice in Wonderland, pronounced his name?

Zigzag and Egypt. The tobacco company called its products Zig-Zag after the “zigzag” alternating process it used, though it may have knowingly used the reference to the ancient town Zig-a-Zag (I have no idea). Anyway, the English word does not have its roots in the Egyptian place name.

Lark. I was delighted to discover that someone had followed my advice and listened to Glinka-Balakirev’s variations. It is true that la-la-la does not at all resemble the lark’s trill, and this argument has been used against those who suggested an onomatopoeic origin of the bird’s name. But, as long as the bird is small, la seems to be a universal syllable in human language representing chirping, warbling, twittering, trilling, and every other sound in the avian kingdom. It was also a pleasure to learn that specialists in Frisian occasionally read my blog. I know the many Frisian cognates of lark thanks to Århammar’s detailed article on this subject (see lark in my bibliography of English etymology).

Bumper. I was unable to find an image of the label used on the bottles of brazen-face beer. My question to someone who has seen the label: “Was there a picture of a saucy mug on it?” (The pun on mug is unintentional.) I am also grateful for the reference to the Gentleman’s Magazine. My database contains several hundred citations from that periodical, but not the one to which Stephen Goranson, a much better sleuth that I am, pointed. This publication was so useful for my etymological bibliography that I asked an extremely careful volunteer to look through the entire set of Lady’s Magazine and of about a dozen other magazines with the word lady in the title. They were a great disappointment: only fashion, cooking, knitting, and all kinds of household work. Women did write letters about words to Notes and Queries, obviously a much more prestigious outlet. However, we picked up a few crumbs even from those sources. The word bomber-nickel puzzled me. I immediately thought of pumpernickel but could not find any connection between the bread and the vessel discussed in the entry I cited. I still see no connection. As for pumpernickel, I am well aware of its origin and discussed it in detail in the entry pimp in my dictionary (pimp, pump, pomp-, pumper-, pamper, and so forth).

Again. It was instructive to see the statistics about the use of the pronunciation again versus agen and to read the ditty in which again has a diphthong multiple times. If I remember correctly, Byron, Shelley, Wordsworth, and others rhymed again only with words like slain, though one never knows to what extent they exploited the so-called rhyme to the eye. Most probably, they did pronounce a diphthong in again.

Scots versus English, as seen in 1760 (continued from the previous gleanings).

- Sc. fresh weather ~ Engl. open weather

- Sc. tender ~ Engl. fickly

- Sc. in the long run ~ Engl. at long run

- Sc. with child to a man ~ Engl. with child by a man (To be continued.)

Happy holidays! We’ll meet again in 2013.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears here, each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears here, each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: (1) Lucas Cranach the Elder’s The Three Graces, 1531. The Louvre via Wikimedia Commons. (2) An illustration of the ogre Grendel from Beowulf by Henrietta Elizabeth Marshall in J. R. Skelton’s Stories of Beowulf (1908) via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Monthly etymology gleanings for December 2012 appeared first on OUPblog.

By Anatoly Liberman

This is a story of again; gain will be added as an afterthought. Throughout the first half of the twentieth century, dictionaries informed their users that again is pronounced with a diphthong, that is, with the same vowel as in the name of the letter A. (I am adding this explanation, because native speakers of English with no knowledge of phonetics seldom realize that the vowel in day, take, main consists of two parts: the nucleus and a glide; the formulation that, for example, a in bait is the “long counterpart of short a” in bat makes matters even worse.) Some people still rhyme again with fain, feign, fane. However, most rhyme it with Ben, den, ten; all the recent British and American dictionaries agree on this point.

The history of the adverb again is surprisingly checkered. In Modern English, the use of the digraphs ai, ay, and ei for short e is, as undergraduate students like to put it, not “very unique”: compare said, says, and heifer. But that does not make the puzzle easier, because says and said stand out as abnormal even in English, in which one can sometimes feel uncertain of how to spell the shortest words. Clearly, the spelling, irrational from today’s point of view, goes back to the pronunciation of old, but tracing the fortunes of each freak is no easy matter. This holds especially for heifer, but again too poses many difficulties.

Only the origin of again is clear. Among its cognates we find German entgegen “opposite” and Old Icelandic í gegn “against.” In the English word, the prefix a- goes back to the preposition on. Old Engl. ongean meant “in the opposite direction” and “back,” not “once more.” The oldest sense of -gain has been preserved in gainsay, literally “speak against.” The Germanic root of -gean and -gegn must have been gag-; its meaning need not occupy our attention, The vowel ea in ongean was long, which means that it consisted of two halves, each of which could be stressed, depending on the word’s place in the sentence, intonation, and emphasis. There was a time when in words of such structure stress shifted from e to a, though it is not clear whether the attested modern dialectal form agan owes its vowel to eá, from éa.

As far back as in Old English, the letter given here as g in ongean designated the sound we now hear in yes, you, and yonder. The interplay of g and y is common in the West Germanic languages. Those who have been exposed to the Berlin dialect know that, for instance, Gegend “area” sounds like yeyend there. In Middle High German, legt “lays” and trägt “carries” were spelled leit and treit. Old Engl. g- also changed to y- before i- and e-, and the modern forms yield and yearn bear witness to that change (their German cognates begin with g-: gelten and begehren). There would have been many more English words like those two but for the Viking raids. In the language of the Scandinavians, g remained “hard,” and that is why Modern Engl. get has not merged in pronunciation with yet. Also, give is a phonetic borrowing from the north, whether directly from the invading Danes or from the northern English dialects in which g- withstood “softening” to y-.

In Middle English, the most common form of again was ayen, still with a long vowel. To an unschooled observer the phonetic history of every well-documented language looks like an endless exercise in futility, a conspiracy invented for obfuscating beginning students. Long vowels become short and some time later undergo secondary lengthening, only to lose the hard-gained length a century or two later. Monophthongs turn into diphthongs, while diphthongs become monophthongs and occupy the slots vacated by their former neighbors. Wouldn’t it have been more natural for them to stay put and avoid playing lobster quadrille? Language is a self-regulating mechanism, and many changes only look erratic, but others are accounted for by the fact that sounds, like people, succumb to contradictory rules: from one point of view it may be expedient for a vowel to lengthen, but from another it would be better if it remained short or became long and then returned to its initial state. Phonetic system is like a modern democracy, which faces chaos and in trying to overcome it produces even greater chaos. There is no end to this process. In the history of again we observe how the original diphthong became a long monophthong, shortened, lengthened, and diphthongized. The coexistence of two modern pronunciations of again reflects those changes. Says and said exhibit partly the same picture, but only the short variants have survived.

AYENBITE OF INWYT

Somewhat unexpectedly,

again is not pronounced

ayen. In the fourteenth century, the Kentish English for “pricks (or rather “bite”) of conscience” was

ayenbite of inwyt, as we know from the title of moralizing prose written in 1340 (compare

backbiting).

Ayen-bite is a

morpheme by morpheme translation of Old French

re-mors “re

morse,” literally “biting with ever-increasing ‘

mordancy’.” But by the seventeenth century the forms with

ag- superseded those with

ay-. As usual in such cases, suspicion falls on northern English or Scandinavian speakers. The reason why in this word the southern and central consonant gave way to northern

g- has never been explained.

Against surfaced as an adverb: Middle Engl. ageines is agein followed by an adverbial suffix. Its final -t is, to use a scholarly term, excrescent. This “parasitic” sound has also made its way after s into amidst, whilst, amongst, and a few others. A well-known vulgarism is acrossed. A similar change affected Old Engl. betweohs ~ betwyx ~ betwux: betwix became betwixt(e), and the idiom betwixt and between is still alive.

In distinction from again, gain (noun and verb) has an easily recoverable past. It is a borrowing of Old French gain (masculine; feminine gagne); the verb was gaigner (Modern French gagner). But the ancient word came to Romance from the Germanic verb for “hunt” and acquired the senses “cultivate land” and “earn.” It follows that gain in gainsay, in which again appears without its old prefix, and gain, as in gainful occupation, are distinct words, and only chance turned them into homophones and allowed them to meet in Modern English. Such is the story of gain1 and gain2. It is more complicated than what one could expect from a blog posted in late December, but nothing venture, nothing win, as the British say, or nothing ventured, nothing gained, as they say in America.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears here, each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears here, each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

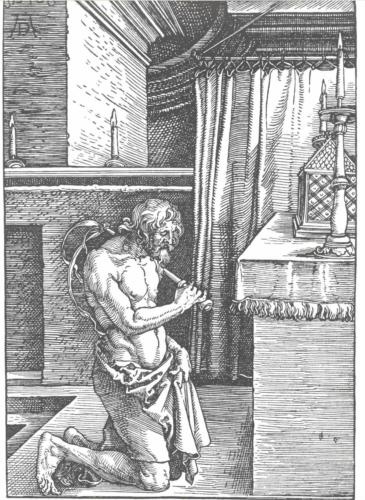

Image credit: King David does repentance Why don’t ‘gain’ and ‘again’ rhyme? appeared first on OUPblog.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE WORDS AGAIN AND AGAINST,

WITH AMIDST, ACROSSED, AND WHILST BEING THROWN IN FOR GOOD MEASURE

By Anatoly Liberman

There are two questions here. First, why does again rhyme with den, fen, ten rather than gain? Second, where did -t in against come from? I’ll begin with against.

Old English had a ramified system of endings. The most common ending of the genitive was -s, which also occurred as a suffix of adverbs, or in words that, by definition, had no case forms at all (adverbs are not declined!). It is easy to detect the traces of the adverbial -s in such modern words as always, (must) needs, and nowadays, and its obscure origin will not interest us here. Some adverbs ending in -s were used with the preposition to before them, for example, togegnes “against” (read both g’s as y) and tomiddes “amid.” They competed with similar and synonymous adverbs having no endings: ongegn and onmiddan. As a result, the hybrid forms emerged with -s at the end and a “wrong” prefix: ageines and amides. Initial a- in them is the continuation of on-; hence our modern forms against and amidst. So far, everything is clear. The tricky part is final t.

Obviously, this -t has no justification in the early history of either against or amidst. According to the usual explanation, both words so often preceded the definite article the that -sth- was simplified (“assimilated”) to st. This explanation is plausible. By way of analogy, it may be added that a similar process has been postulated for the verb hoist. It surfaced in English texts in the 16th century in the form hoise, and all its native predecessors and cognates elsewhere in Germanic look like it. Perhaps the infinitive was changed under the influence of the preterit and the past participle (as in the now proverbial to be hoist with one’s own petard), but, not inconceivably, in the phrase hoise the flag the same process occurred as in ageines the/amides the. (I have seen the conjecture that -st goes back to the superlative degree of adjectives. This reconstruction is fanciful.)

However, t also developed in words that did not always precede the definite article. Thus, earnest “pledge money,” a noun with a long an intricate history, was first attested in the form erles. Here the influence of the all-important adjective earnest, from Old Engl. earnost, should not be ruled out. Tapestry is another borrowing from French (tapisserie; compare Engl. on the tapis, literally, “on the table cloth,” a calque of French sur la tapis: tapis and tapestry are of course related). The inserted t in tapestry is called a parasitic sound that developed between s and r—not much of an explanation, even though it is possibly true. Whilst is from whiles, which, like against, had no historical -t. Both words seem to have developed along similar lines, but the troublesome consonant may be �

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears here, each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”