new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: 2016 middle grade historical fiction, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 6 of 6

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: 2016 middle grade historical fiction in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 11/13/2016

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

middle grade historical fantasy,

Kate Saunders,

Best Books of 2016,

2016 imports,

2016 reviews,

Reviews 2016,

2016 middle grade fantasy,

2016 middle grade historical fiction,

Reviews,

middle grade fantasy,

Random House,

Best Books,

Delacorte Press,

WWI,

middle grade historical fiction,

Add a tag

Five Children on the Western Front

Five Children on the Western Front

By Kate Saunders

Delacorte Press (an imprint of Random House)

$16.99

ISBN: 978-0-553-49793-9

Ages 9-12

On shelves now

Anytime someone writes a new prequel or sequel to an old children’s literary classic, the first question you have to ask is, “Was this necessary?” And nine times out of ten, the answer is a resounding no. No, we need no further adventures in the 100-Acre Woods. No, there’s very little reason to speculate on precisely what happened to Anne before she got to Green Gables. But once in a while an author gets it right. If they’re good they’ll offer food for thought, as when Jacqueline Kelly wrote, Return to the Willows (the sequel to The Wind in the Willows) and Geraldine McCaughrean wrote Peter Pan in Scarlet. And if they’re particularly talented, then they’ll do the series one better. They’ll go and make it smart and pertinent and real and wonderful. They may even improve upon the original. The idea that someone would write a sequel to Five Children and It (and to a lesser extent The Phoenix and the Carpet and The Story of the Amulet) is well-nigh short of ridiculous. I mean, you could do it, sure, but why? What’s the point? Well, as author Kate Saunders says of Nesbit’s classic, “Bookish nerd that I was, it didn’t take me long to work out that two of E. Nesbit’s fictional boys were of exactly the right ages to end up being killed in the trenches…” The trenches of WWI, that is. Suddenly we’ve an author who dares to meld the light-hearted fantasy of Nesbit’s classic with the sheer gut-wrenching horror of The War to End All Wars. The crazy thing is, she not only pulls it off but she creates a great novel in the process. One that deserves to be shelved alongside Nesbit’s original for all time.

Once upon a time, five children found a Psammead, or sand fairy, in their back garden. Nine years later, he came back. A lot has happened since this magical, and incredibly grumpy, friend was in the children’s lives. The world stands poised on the brink of WWI. The older children (Cyril, Anthea, Robert, and Jane) have all become teenagers, while the younger kids (Lamb and newcomer Polly) are the perfect age to better get to know the old creature’s heart. As turns out, he has none, or very little to speak of. Long ago, in ancient times, he was worshipped as a god. Now the chickens have come home to roost and he must repent for his past sins or find himself stuck in a world without his magic anymore. And the children? No magic will save them from what’s about to come.

A sequel to a book published more than a hundred years ago is a bit more of a challenge than writing one published, say, fifty. The language is archaic, the ideas outdated, and then there’s the whole racism problem. But even worse is the fact that often you’ll find character development in classic titles isn’t what it is today. On the one hand that can be freeing. The author is allowed to read into someone else’s characters and present them with the necessary complexity they weren’t originally allowed. But it can hem you in as well. These aren’t really your characters, after all. Clever then of Ms. Saunders to age the Lamb and give him a younger sister. The older children are all adolescents or young adults and, by sheer necessity, dull by dint of age. Even so, Saunders does a good job of fleshing them out enough that you begin to get a little sick in the stomach wondering who will live and who will die.

This naturally begs the question of whether or not you would have to read Five Children and It to enjoy this book. I think I did read it a long time ago but all I could really recall was that there were a bunch of kids, the Psammead granted wishes, the book helped inspire the work of Edgar Eager, and the youngest child was called “The Lamb”. Saunders tries to play the book both ways then. She puts in enough details from the previous books in the series to gratify the Nesbit fans of the world (few though they might be) while also catching the reader up on everything that came before in a bright, brisk manner. You do read the book feeling like not knowing Five Children and It is a big gaping gap in your knowledge, but that feeling passes as you get deeper and deeper into the book.

One particular element that Ms. Saunders struggles with the most is the character of the Psammead. To take any magical creature from a 1902 classic and to give him hopes and fears and motivations above and beyond that of a mere literary device is a bit of a risk. As I’ve mentioned, I’ve not read “Five Children and It” in a number of years so I can’t recall if the Psammead was always a deposed god from ancient times or if that was entirely a product from the brain of Ms. Saunders. Interestingly, the author makes a very strong attempt at equating the atrocities of the Psammead’s past (which are always told in retrospect and are never seen firsthand) with the atrocities being committed as part of the war. For example, at one point the Psammead is taken to the future to speak at length with the deposed Kaiser, and the two find they have a lot in common. It is probably the sole element of the book that didn’t quite work for me then. Some of the Psammead’s past acts are quite horrific, and he seems pretty adamantly disinclined to indulge in any serious self-examination. Therefore his conversion at the end of the book didn’t feel quite earned. It’s foolish to wish a 250 page children’s novel to be longer, but I believe just one additional chapter or two could have gone a long way towards making the sand fairy’s change of heart more realistic. Or, at the very least, comprehensible.

When Ms. Saunders figured out the Cyril and Robert were bound for the trenches, she had a heavy task set before her. On the one hand, she was obligated to write with very much the same light-hearted tone of the original series. On the other hand, the looming shadow of WWI couldn’t be downplayed. The solution was to experience the war in much the same way as the characters. They joke about how short their time in the battle will be, and then as the book goes along the darkness creeps into everyday life. One of the best moments, however, comes right at the beginning. The children, young in the previous book, take a trip from 1905 to 1930, visit with their friend the professor, and return back to their current year. Anthea then makes an off-handed comment that when she looked at the photos on the wall she saw plenty of ladies who looked like young versions of their mother but she couldn’t find the boys. It simply says after that, “Far away in 1930, in his empty room, the old professor was crying.”

So do kids need to have read Five Children and It to enjoy this book? I don’t think so, honestly. Saunders recaps the originals pretty well, and I can’t help but have high hopes for the fact that it may even encourage some kids to seek out the originals. I do meet kids from time to time that are on the lookout for historical fantasies, and this certainly fits the bill. Ditto kids with an interest in WWI and (though this will be less common as the years go by) kids who love Downton Abbey. It would be remarkably good for them. Confronting issues of class, disillusion, meaningless war, and empathy, the book transcends its source material and is all the better for it. A beautiful little risk that paid off swimmingly in the end. Make an effort to seek it out.

On shelves now.

Source: Final copy sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

Other Blog Reviews: educating alice

Professional Reviews:

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 9/26/2016

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reviews,

Best Books,

Candlewick,

middle grade historical fiction,

Anne Nesbet,

Best Books of 2016,

2016 reviews,

Reviews 2016,

2016 middle grade fiction,

2017 Newbery contenders,

2016 middle grade historical fiction,

Add a tag

Cloud and Wallfish

Cloud and Wallfish

By Anne Nesbet

Candlewick Press

$16.99

ISBN: 978-0-7636-8803-5

Ages 9-12

On shelves now

Historical fiction is boring. Right? That’s the common wisdom on the matter, certainly. Take two characters (interesting), give them a problem (interesting), and set them in the past (BOOOOOORING!). And to be fair, there are a LOT of dull-as-dishwater works of historical fiction out there. Books where a kid has to wade through knee-deep descriptions, dates, facts, and superfluous details. But there is pushback against this kind of thinking. Laurie Halse Anderson, for example, likes to call her books (Chains, Forge, Ashes, etc.) “historical thrillers”. People are setting their books in unique historical time periods. And finally (and perhaps most importantly) we’re seeing a lot more works of historical fiction that are truly fun to read. Books like The War That Saved My Life by Kimberly Brubaker Bradley, or One Crazy Summer by Rita Williams-Garcia, or My Near-Death Adventures by Alison DeCamp, or ALL of Louise Erdrich’s titles for kids. Better add Cloud and Wallfish by Anne Nesbet to that list as well. Doing what I can only characterize as the impossible, Nesbet somehow manages to bring East Germany in 1989 to full-blown, fascinating life. Maybe you wouldn’t want to live there, but it’s certainly worth a trip.

His name is Noah. Was Noah. It’s like this, one minute you’re just living your life, normal as you please, and the next your parents have informed you that your name is a lie, your birth date is wrong, and you’re moving to East Berlin. The year is 1989 and as Noah (now Jonah)’s father would say, there’s a definite smell of history in the air. His mother has moved the family to this new city as part of her research into education and stuttering (an impediment that Noah shares) for six months. But finding himself unable to attend school in a world so unlike the one he just left, the boy is lonely. That’s why he’s so grateful when the girl below his apartment, Claudia, befriends him. But there are secrets surrounding these new friends. How did Claudia’s parents recently die? Why are Noah’s parents being so mysterious? And what is going on in Germany? With an Iron Curtain shuddering on its foundations, Noah’s not just going to smell that history in the air. He’s going to live it, and he’s going to get a friend out of the bargain as well.

It was a bit of a risk on Nesbet’s part to begin the book by introducing us to Noah’s parents right off the bat as weirdly suspicious people. It may take Noah half a book to create a mental file on his mom, but those of us not related to the woman are starting our own much sooner. Say, from the minute we meet her. It was very interesting to watch his parents upend their son’s world and then win back his trust by dint of their location as well as their charm and evident love. It almost reads like a dare from one author to another. “I bet you can’t make a reader deeply distrust a character’s parents right from the start, then make you trust them again, then leave them sort of lost in a moral sea of gray, but still likable!” Challenge accepted!

Spoiler Alert on This Paragraph (feel free to skip it if you like surprises): Noah’s mom is probably the most interesting parent you’ll encounter in a children’s book in a long time. By the time the book is over you know several things. 1. She definitely loves Noah. 2. She’s also using his disability to further her undercover activities, just as he fears. 3. She incredibly frightening. The kind of person you wouldn’t want to cross. She and her husband are utterly charming but you get the distinct feeling that Noah’s preternatural ability to put the puzzle pieces of his life together is as much nature as it is nurture. Coming to the end of the book you see that Noah has sent Claudia postcards over the years from places all over the world. Never Virginia. One could read that a lot of different ways but I read it as his mother dragging him along with her from country to country. There may never be a “home” for Noah now. But she loves him, right? I foresee a lot of really interesting bookclub discussions about the ending of this book, to say nothing about how we should view his parents.

As I mentioned before, historical fiction that’s actually interesting can be difficult to create. And since 1989 is clear-cut historical fiction (this is the second time a character from the past shared my birth year in a children’s book . . . *shudder*) Nesbet utilizes several expository techniques to keep young readers (and, let’s face it, a lot of adult readers) updated on what precisely is going on. From page ten onward a series of “Secret Files” boxes will pop up within the text to give readers the low-down. These are written in a catchy, engaging style directly to the reader, suggesting that they are from the point of view of an omniscient narrator who knows the past, the future, and the innermost thoughts of the characters. So in addition to the story, which wraps you in lies and half-truths right from the start to get you interested, you have these little boxes of explanation, giving you information the characters often do not have. Some of these Secret Files are more interesting than others, but as with the Moby Dick portions in Louis Sachar’s The Cardturner, readers can choose to skip them if they so desire. They should be wary, though. A lot of pertinent information is sequestered in these little boxes. I wouldn’t cut out one of them for all the wide wide world.

Another way Nesbet keeps everything interesting is with her attention to detail. The author that knows the minutia of their fictional world is an author who can convince readers that it exists. Nesbet does this by including lots of tiny details few Americans have ever known. The pirated version of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz that was disseminated for years throughout the German Democratic Republic? I had no idea. The listing of television programs available there? Very funny (did I mention the book is funny too?). Even the food you could get in the grocery store and the smell of the coal-choked air feels authentic.

Of course, you can load your book down with cute boxes and details all day and still lose a reader if they don’t relate to the characters. Noah could easily be reduced to one of those blank slate narrators who go through a book without a clear cut personality. I’m happy to report that this isn’t the case here. And I appreciated the Claudia was never a straight victim or one of those characters that appears impervious to the pain in her life. Similarly, Noah is a stutterer but the book never throws the two-dimensional bully in his path. His challenges are all very strange and unique to his location. I was also impressed by how Nesbet dealt with Claudia’s German (she makes up words or comes up with some Noah has never heard of and so Nesbet has the unenviable job of making that clear on the page). By the same token, Noah has a severe stutter, but having read the whole book I’m pretty sure Nesbet only spells the stutter out on the page once. For every other time we’re told about it after the fact or as it is happening.

I’ve said all this without, somehow, mentioning how lovely Nesbet’s writing is. The degree to which she’s willing to go deep into her material, plucking out the elements that will resonate the most with her young readers, is masterful. Consider a section that explains what it feels like to play the role of yourself in your own life. “This is true even for people who aren’t crossing borders or dealing with police. Many people in middle school, for instance, are pretending to be who they actually are. A lot of bad acting is involved.” Descriptions are delicious as well. When Claudia comes over for dinner after hearing about the death of her parents Nesbet writes, “Underneath the bristles, Noah could tell, lurked a squishy heap of misery.”

There’s little room for nuance in Nesbet’s Berlin, that’s for sure. The East Berliners we meet are either frightened, in charge, or actively rebelling. In her Author’s Note, Nesbet writes about her time in the German Democratic Republic in early 1989, noting where a lot of the details of the book came from. She also mentions the wonderful friends she had there at that time. Noah, by the very plot in which he finds himself, would not be able to meet these wonderful people. As such, he has a black-and-white view of life in East Berlin. And it’s interesting to note that when his classmates talk up the wonders of their society, he never wonders if anything they tell him is true. Is everyone employed? At what price? There is good and bad and if there is nuance it is mostly found in the characters like Noah’s mother. Nesbet herself leaves readers with some very wise words in her Author’s Note when she says to child readers, “Truth and fiction are tangled together in everything human beings do and in every story they tell. Whenever a book claims to be telling the truth, it is wise (as Noah’s mother says at one point) to keep asking questions.” I would have liked a little more gray in the story, but I can hardly think of a better lesson to impart to children in our current day and age.

In many way, the book this reminded me of the most was Katherine Paterson’s Bridge to Terabithia. Think about it. A boy desperate for a friend meets an out-of-the-box kind of girl. They invent a fantasyland together that’s across a distinct border (in this book Claudia imagines it’s just beyond the Wall). Paterson’s book was a meditation on friendship, just like Nesbet’s. Yet there is so much more going on here. There are serious thoughts about surveillance (something kids have to think about a lot more today), fear, revolution, loyalty, and more than all this, what you have to do to keep yourself sane in a world where things are going mad. Alice Through the Looking Glass is referenced repeatedly, and not by accident. Noah has found himself in a world where the rules he grew up with have changed. As a result he must cling to what he knows to be true. Fortunately, he has a smart author to help him along the way. Anne Nesbet always calls Noah by his own name, even when her characters don’t. He is always Noah to us and to himself. That he finds himself in one of the most interesting and readable historical novels written for kids is no small thing. Nesbet outdoes herself. Kids are the beneficiaries.

On shelves now.

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

Professional Reviews:

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 9/4/2016

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reviews,

historical fiction,

Louise Erdrich,

funny books,

Harper Collins,

Best Books,

middle grade historical fiction,

Best Books of 2016,

2016 reviews,

Reviews 2016,

2016 middle grade historical fiction,

2016 funny books,

Add a tag

Makoons

Makoons

By Louise Erdrich

Harper Collins

$16.99

ISBN: 9780060577933

Ages 7-12

On shelves now

They say these days you can’t sell a novel for kids anymore without the book having some kind of “sequel potential”. That’s not really true, but there are a heck of a lot of series titles out there for the 7 to 12-year-old set, that’s for sure. New series books for children are by their very definition sort of odd for kids, though. If you’re an adult and you discover a new series, waiting a year or two for the next book to come out is a drop in the bucket. Years fly by for grown-ups. The wait may be mildly painful but it’s not going to crush you. But series for kids? That’s another matter entirely. Two years go by and the child has suddenly become an entirely different person. They may have switched their loyalties from realistic historical fiction to fantasy or science fiction or (heaven help us) romance even! It almost makes more sense just to hand them series that have already completed their runs, so that they can speed through them without breaking the spell. Almost makes more sense . . . but not quite. Not so long as there are series like “The Birchbark House Series” by Louise Erdrich. It is quite possibly the only historical fiction series currently underway for kids that has lasted as long as seventeen years and showing no sign of slowing down until it reaches its conclusion four books from now, Erdrich proves time and time again that she’s capable of ensnaring new readers and engaging older ones without relying on magic, mysteries, or post-apocalyptic mayhem. And if she manages to grind under her heel a couple stereotypes about what a book about American Indians in the past is “supposed” to be (boring/serious/depressing) so much the better.

Chickadee is back, and not a second too soon. Had he been returned to his twin brother from his kidnapping any later, it’s possible that Makoons would have died of the fever that has taken hold of his body. As it is, Chickadee nurses his brother back to health, but not before Makoons acquires terrifying visions of what is to come. Still, there’s no time to dwell on that. The buffalo are on the move and his family and tribe are dedicated to sustaining themselves for the winter ahead. There are surprises along the way as well. A boasting braggart by the name of Gichi Noodin has joined the hunt, and his posturing and preening are as amusing to watch as his mistakes are vast. The tough as nails Two Strike has acquired a baby lamb and for reasons of her own is intent on raising it. And the twin brothers adopt a baby buffalo of their own, though they must protect it against continual harm. All the while the world is changing for Makoons and his family. Soon the buffalo will leave, more settlers will displace them, and three members of the family will leave, never to return. Fortunately, family sustains, and while the future may be bleak, the present has a lot of laughter and satisfaction waiting at the end of the day.

While I have read every single book in this series since it began (and I don’t tend to follow any other series out there, except possibly Lockwood & Co.) I don’t reread previous books when a new one comes out. I don’t have to. Neither, I would argue, would your kids. Each entry in this series stands on its own two feet. Erdrich doesn’t spend inordinate amounts of time catching the reader up, but you still understand what’s going on. And you just love these characters. The books are about family, but with Makoons I really felt the storyline was more about making your own family than the family you’re born into. At the beginning of this book Makoons offers the dire prediction that he and his brother will be able to save their family members, but not all of them. Yet by the story’s end, no matter what’s happened, the family has technically only decreased by two people, because of the addition of another.

Erdrich has never been afraid of filling her books with a goodly smattering of death, dismemberment, and blood. I say that, but these do not feel like bloody books in the least. They have a gentleness about them that is remarkable. Because we are dealing with a tribe of American Indians (Ojibwe, specifically) in 1866, you expect this book to be like all the other ones out there. Is there a way to tell this story without lingering on the harm caused by the American government to Makoons, his brother, and his people? Makoons and his family always seem to be outrunning the worst of the American government’s forces, but they can’t run forever. Still, I think it’s important that the books concentrate far more on their daily lives and loves and sorrows, only mentioning the bloodthirsty white settlers on occasion and when appropriate. It’s almost as if the reader is being treated in the same way as Makoons and his brother. We’re getting some of the picture but we’re being spared its full bloody horror. That is not to say that this is a whitewashed narrative. It isn’t at all. But it’s nice that every book about American Indians of the past isn’t exactly the same. They’re allowed to be silly and to have jokes and fun moments too.

That humor begs a question of course. Question: When is it okay to laugh at a character in a middle grade novel these days? It’s not a simple question. With a high concentration on books that promote kindness rather than bullying, laughing at any character, even a bad guy, is a tricky proposition. And that goes double if the person you’re laughing at is technically on your side. Thank goodness for self-delusion. As long as a character refuses to be honest with him or herself, the reader is invited to ridicule them alongside the other characters. It may not be nice, but in the world of children’s literature it’s allowed. So meet Gichi Noodin, a pompous jackass of a man. This is the kind of guy who could give Narcissus lessons in self-esteem. He’s utterly in love with his own good looks, skills, you name it. For this reason he’s the Falstaff of the book (without the melancholy). He serves a very specific purpose in the book as the reader watches his rise, his fall, and his redemption. It’s not very often that the butt of a book’s jokes is given a chance to redeem himself, but Gichi Noodin does precisely that. That storyline is a small part of the book, smaller even than the tale of Two Strike’s lamb, but I loved the larger repercussions. Even the butt of the joke can save the day, given the chance.

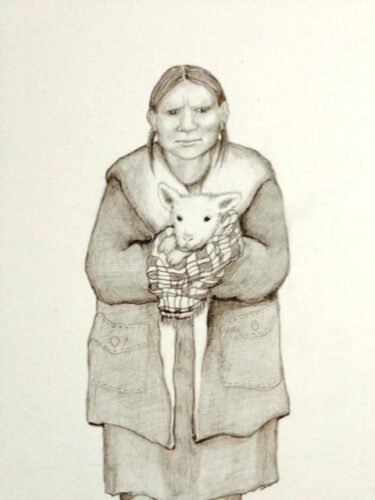

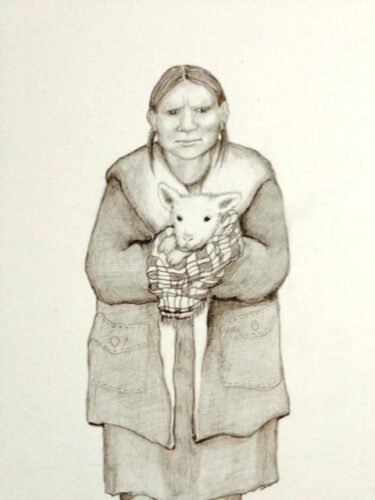

As with all her other books Erdrich does a E.L. Konigsburg and illustrates her own books (and she can even do horses – HORSES!). Her style is, as ever, reminiscent of Garth Williams’ with soft graphite pencil renderings of characters and scenes. These are spotted throughout the chapters regularly, and combined with the simplicity of the writing they make the book completely appropriate bedtime reading for younger ages. The map at the beginning is particularly keen since it not only highlights the locations in each part of the story but also hints at future storylines to come. Of these pictures the sole flaw is the book jacket. You see the cover of this book is a touch on the misleading side since at no point in this story does Makoons ever attempt to feed any baby bears (a terrible idea, namesake or no). Best to warn literal minded kids from the start that that scene is not happening. Then again, this appears to be a scene from the first book in the series, The Birchbark House, where Makoons’ mother Omakayas feeds baby bears as a girl. Not sure why they chose to put it on the cover this book but it at least explains where it came from.

As with all her other books Erdrich does a E.L. Konigsburg and illustrates her own books (and she can even do horses – HORSES!). Her style is, as ever, reminiscent of Garth Williams’ with soft graphite pencil renderings of characters and scenes. These are spotted throughout the chapters regularly, and combined with the simplicity of the writing they make the book completely appropriate bedtime reading for younger ages. The map at the beginning is particularly keen since it not only highlights the locations in each part of the story but also hints at future storylines to come. Of these pictures the sole flaw is the book jacket. You see the cover of this book is a touch on the misleading side since at no point in this story does Makoons ever attempt to feed any baby bears (a terrible idea, namesake or no). Best to warn literal minded kids from the start that that scene is not happening. Then again, this appears to be a scene from the first book in the series, The Birchbark House, where Makoons’ mother Omakayas feeds baby bears as a girl. Not sure why they chose to put it on the cover this book but it at least explains where it came from.

It is interesting that the name of this book is Makoons since Chickadee shares as much of the spotlight, if not a little more so, than his sickly brother. That said, it is Makoons who has the vision of the future, Makoons who offers the haunting prediction at the story’s start, and Makoons who stares darkly into an unknown void at the end, alone in the misery he knows is certain to come. Makoons is the Cassandra of this story, his predictions never believed until they are too late. And yet, this isn’t a sad or depressing book. The hope that emanates off the pages survives the buffalos’ sad departure, the sickness that takes two beloved characters, and the knowledge that the only thing this family can count on in the future is change. But they have each other and they are bound together tightly. Even Pinch, that trickster of previous books, is acquiring an odd wisdom and knowledge of his own that may serve the family well into the future. Folks often recommend these books as progressive alternatives to Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House books, but that’s doing them a disservice. Each one of these titles stands entirely on its own, in a world of its own making. This isn’t some sad copy of Wilder’s style but a wholly original series of its own making. The kid who starts down the road with this family is going to want to go with them until the end. Even if it takes another seventeen years. Even if they end up reading the last few books to their own children. Whatever it takes, we’re all in this together, readers, characters, and author. Godspeed, Louise Erdrich.

For ages 7-12

Source: Final copy sent from publisher for review.

Professional Reviews:

Other Blog Reviews: BookPage

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 7/6/2016

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reviews,

middle grade fiction,

Best Books,

Dutton Children's Books,

middle grade historical fiction,

Adam Gidwitz,

Penguin Random House,

Hatem Aly,

Best Books of 2016,

2016 reviews,

Reviews 2016,

2016 middle grade fiction,

2016 middle grade historical fiction,

Add a tag

The Inquisitor’s Tale or, The Three Magical Children and Their Holy Dog

The Inquisitor’s Tale or, The Three Magical Children and Their Holy Dog

By Adam Gidwitz

Illuminated by Hatem Aly

Dutton Children’s Books (an imprint of Penguin Random House)

$17.99

ISBN: 978-0-525-42616-5

Ages 9 and up

On shelves September 27th

God’s hot this year.

To be fair, God has had some fairly strong supporters for quite some time. So if I’m going to clarify that statement a tad, God’s hot in children’s literature this year. Even then, that sentence is pretty vague. Here in America there are loads of Christian book publishers out there, systematically putting out title after title after title each and every year about God, to say nothing of publishers of other religions as well. Their production hasn’t increased hugely in 2016, so why the blanket statement? A final clarification, then: God is hot in children’s books from major non-Christian publishers this year. Ahhhh. That’s better. Indeed, in a year when serious literary consideration is being heaped upon books like John Hendrix’s Miracle Man, in walks Adam Gidwitz and his game changing The Inquisitor’s Tale. Now I have read my fair share of middle grade novels for kids, and I tell you straight out that I have never read a book like this. It’s weird, and unfamiliar, and religious, and irreligious, and more fun than it has any right to be. Quite simply, Gidwitz found himself a holy dog, added in a couple proto-saints, and voila! A book that’s part superhero story, part quixotic holy quest, and part Canterbury Tales with just a whiff of intrusive narration for spice. In short, nothing you’ve encountered in all your livelong days. Bon appétit.

The dog was dead to begin with. A greyhound with a golden muzzle that was martyred in defense of a helpless baby. As various pub goers gather in the year 1242 to catch a glimpse of the king, they start telling stories about this dog that came back from the dead, its vision-prone mistress (a peasant girl named Jeanne), a young monk blessed with inhuman strength (William, son of a lord and a North African woman), and a young Jewish boy with healing capabilities (Jacob). These three very different kids have joined together in the midst of a country in upheaval. Some see them as saints, some as the devil incarnate, and before this tale is told, the King of France himself will seek their very heads. An extensive Author’s Note and Annotated Bibliography appear at the end.

If you are familiar with Mr. Gidwitz’s previous foray into middle grade literature (the Grimm series) then you know he has a penchant for giving the child reader what it wants. Which is to say, blood. Lots of it. In his previous books he took his cue from the Grimm brothers and their blood-soaked tales. Here his focus is squarely on the Middle Ages (he would thank you not to call them “The Dark Ages”), a time period that did not lack for gore. The carnage doesn’t really begin in earnest until William starts (literally) busting heads, and even then the book feels far less sanguine than Gidwitz’s other efforts. I mean, sure, dogs die and folks are burned alive, but that’s pretty tame by Adam’s previous standards. Of course, what he lacks in disembowelments he makes up for with old stand-bys like vomit and farts. Few can match the man’s acuity for disgusting descriptions. He is a master of the explicit and kids just eat that up. Not literally of course. That would be gross. As a side note, he has probably included the word “ass” more times in this book than all the works of J.M. Barrie and Roald Dahl combined. I suspect that if this book is ever challenged in schools or libraries it won’t be for the copious entrails or discussions about God, but rather because at one point the word “ass” (as it refers to a donkey) appears three times in quick, unapologetic succession. And yes, it’s hilarious when it does.

So let’s talk religious persecution, religious fundamentalism, and religious tolerance. As I write this review in 2016 and politicians bandy hate speech about without so much as a blink, I can’t think of a book written for kids more timely than this. Last year I asked a question of my readers: Can a historical children’s book contain protagonists with prejudices consistent with their time period? Mr. Gidwitz seeks to answer that question himself. His three heroes are not shining examples of religious tolerance born of no outside influence. When they escape together they find that they are VERY uncomfortable in one another’s presence. Mind you, I found William far more tolerant of Jacob than I expected (though he does admittedly condemn Judaism once in the text). His dislike of women is an interesting example of someone rejecting some but not all of the childhood lessons he learned as a monk. Yet all three kids fear one another as unknown elements and it takes time and a mutually agreed upon goal to get them from companionship to real friendship.

As I mentioned at the start of this review, religion doesn’t usually get much notice in middle grade books for kids from major publishers these days. And you certainly won’t find discussions about the differences between Christianity and Judaism, as when the knight Marmeluc tries to determine precisely what it is to be Jewish. What I appreciated about this book was how Gidwitz distinguished between the kind of Christianity practiced by the peasants versus the kind practiced by the educated and rich. The peasants have no problem worshipping dogs as saints and even the local priest has a wife that everyone knows he technically isn’t supposed to have. The educated and rich then move to stamp out these localized beliefs which, let’s face it, harken back to the people’s ancestors’ paganism.

Race also comes up a bit, with William’s heritage playing a part now and then, but the real focus is reserved for the history of Christian/Jewish interactions. Indeed, in his wildly extensive Author’s Note at the end, Gidwitz makes note of the fact that race relations in Medieval Europe were very different then than today. Since it preceded the transatlantic slave trade, skin color was rare and contemporary racism remains, “the modern world’s special invention.” There will probably still be objections to the black character having the strength superpower rather than the visions or healing, but he’s also the best educated and intelligent of the three. I don’t think you can ignore that fact.

As for the writing itself, that’s what you’re paying your money for at the end of the day. Gidwitz is on fire here, making medieval history feel fresh and current. For example, when the Jongleur says that some knights are, “rich boys who’ve been to the wars . . . Not proper at all. But still rich,” that’s a character note slid slyly into the storytelling. Other lines pop out at you too. Here are some of my other favorites:

• About that Jongleur, “… he looks like the kind of child who has seen too much of life, who’s seen more than most adults. His eyes are both sharp and dead at the same time. As if he won’t miss anything, because he’s seen it all already.”

• “Jeanne’s mother’s gaze lingered on her daughter another moment, like an innkeeper waiting for the last drop of ale from the barrel tap.”

• “The lord and lady welcomed the knights warmly. Well, the lady did. Lord Bertulf just sat in his chair behind the table, like a stick of butter slowly melting.”

• “Inside her, grand castles of comprehension, models of the world as she had understood it, shivered.”

• And Gidwitz may also be the only author for children who can write a sentence that begins, “But these marginalia contradicted the text…” and get away with it.

Mind you, Gidwitz paints himself into a pretty little corner fairly early on. To rest this story almost entirely on the telling of tales in a pub, you need someone who doesn’t just know the facts of one moment or the next but who could claim to know our heroes’ interior life. So each teller comes to mention each child’s thoughts and feelings in the course of their tale. The nun in the book bears the brunt of this sin, and rather than just let that go Gidwitz continually has characters saying things like, “I want to know if I’m sitting at a table filled with wizards and mind readers.” I’m not sure if I like the degree to which Gidwitz keeps bringing this objection up, or if it detracts from the reading. What I do know is that he sort of cheats with the nun. She’s the book’s deux ex machina (or, possibly the diaboli ex machina) acting partly as an impossibility and partly as an ode to the author’s love of silver haired librarians and teachers out there with “sparkling eyes, and a knowing smile.”

Since a large portion of the story is taken up with saving books as objects, it fits that this book itself should be outfitted with all the beauties of its kind. If we drill down to the very mechanics of the book, we find ourselves admiring the subtleties of fonts. Every time a tale switches between the present day and the story being told, the font changes as well. But to do it justice, the story has been illuminated (after a fashion) by artist Hatem Aly. I have not had the opportunity to see the bulk of his work on this story. I do feel that the cover illustration of William is insufficiently gargantuan, but that’s the kind of thing they can correct in the paperback edition anyway.

Fairy tales and tales of saints. The two have far more in common than either would like to admit. Seen in that light, Gidwitz’s transition from pure unadulterated Grimm to, say, Lives of the Improbable Saints and Legends of the Improbable Saints is relatively logical. Yet here we have a man who has found a way to tie-in stories about religious figures to the anti-Semitism that is still with us to this day. At the end of his Author’s Note, Gidwitz mentions that as he finished this book, more than one hundred and forty people were killed in Paris by terrorists. He writes of Medieval Europe, “It was a time when people were redefining how they lived with the ‘other,’ with people who were different from them.” The echoes reverberate today. Says Gidwitz, “I can think of nothing sane to say about this except this book.” Sermonizers, take note.

On shelves September 27th.

Like This? Then Try:

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 5/5/2016

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reviews,

middle grade fiction,

Penguin,

Best Books,

Dutton Children's Books,

middle grade historical fiction,

bully books,

Penguin Random House,

Best Books of 2016,

Reviews 2016,

2016 middle grade fiction,

2016 middle grade historical fiction,

Lauren Wolk,

Add a tag

Wolf Hollow

Wolf Hollow

By Lauren Wolk

Dutton Children’s Books (an imprint of Penguin Random House)

$16.99

ISBN: 978-1101994825

Ages 10 and up

On shelves now.

I am not what you might call a very brave reader. This is probably why I primarily consume children’s literature. I might puff myself up with a defense that lists the many fine aspects of this particular type of writing and believe it too, but sometimes when you catch me in a weak moment I might confess that another reason I like reading books for kids is that the content is so very “safe” in comparison to books for adults. Disturbing elements are kept at a minimum. There’s always a undercurrent of hope running through the book, promising that maybe we don’t live in a cold, cruel, calculating universe that cares for us not one jot. Even so, that doesn’t mean that I don’t sometimes have difficulty with books written for, oh say, 10-year-olds. I do. I’m not proud of it, but I do. So when I flipped to the back of Wolf Hollow mid-way through reading it, I want to tell you that I did so not because I wanted to spoil the ending for myself but because I honestly couldn’t turn another page until I knew precisely how everything was going to fall out. In her debut children’s book, Lauren Wolk dives head first into difficult material. A compelling author, the book is making the assumption that child readers will want to see what happens to its characters, even when the foreshadowing is so thick you’d need a knife to cut through it. Even when the ending may not be the happy one everyone expects. And you know what? The book might be right.

It is fair to say that if Betty Glengarry hadn’t moved to western Pennsylvania in the autumn of 1943 then Annabelle would not have needed to become a liar later. Betty looks the part of the blond, blue-eyed innocent, but that exterior hides a nasty spirit. Within days of her arrival she’s threatened Annabelle and said in no uncertain terms that unless she’s brought something special she’ll take it out on the girl’s little brothers. Annabelle is saved from Betty’s threats by Toby, a war veteran with issues of his own. That’s when Betty begins a more concentrated campaign of pain. Rocks are thrown. Accusations made. There’s an incident that comes close to beheading someone. And then, when things look particularly bad, Annabelle disappears. And so does Toby. Now Annabelle finds herself trying to figure out what is right, what is wrong, and whether lies can ever lead people to the truth.

Right off the bat I’m going to tell you that this is a spoiler-rific review. I’ve puzzled it over but I can’t for the life of me figure out how I’d be able to discuss what Wolk’s doing here without giving away large chunks o’ plot. So if you’re the kind of reader who prefers to be surprised, walk on.

All gone? Okay. Let’s get to it.

First and foremost, let’s talk about why this book was rough going for me. I understand that “Wolf Hollow” is going to be categorized and tagged as a “bully book” for years to come, and I get that. But Betty, the villain of the piece, isn’t your average mean girl. I hesitate to use the word “sadistic” but there’s this cold undercurrent to her that makes for a particularly chilling read. Now the interesting thing is that Annabelle has a stronger spine than, say, I would in her situation. Like any good baddie, Betty identifies the girl’s weak spot pretty quickly (Annabelle’s younger brothers) and exploits it as soon as she is able. Even so, Annabelle does a good job of holding her own. It’s when Betty escalates the threat (and I do mean escalates) that you begin to wonder why the younger girl is so adamant to keep her parents in the dark about everything. If there is any weak spot in the novel, it’s a weak spot that a lot of books for middle grade titles share. Like any good author, Wolk can’t have Annabelle tattle to her parents because otherwise the book’s momentum would take a nose dive. Fortunately this situation doesn’t last very long and when Annabelle does at last confide in her very loving parents Betty adds manipulation to her bag of tricks. It got to the point where I honestly had to flip to the back of the book to see what would happen to everyone and that is a move I NEVER do. But there’s something about Betty, man. I think it might have something to do with how good she is at playing to folks’ preexisting prejudices.

Originally author Lauren Wolk wrote this as a novel for adults. When it was adapted into a book for kids she didn’t dumb it down or change the language in a significant manner. This accounts for some of the lines you’ll encounter in the story that bear a stronger import than some books for kids. Upon finding the footsteps of Betty in the turf, Annabelle remarks that they “were deep and sharp and suggested that she was more freighted than she could possibly be.” Of Toby, “He smelled a lot like the woods in thaw or a dog that’s been out in the rain. Strong, but not really dirty.” Maybe best of all, when Annabelle must help her mother create a salve for Betty’s poison ivy, “Together, we began a brew to soothe the hurt I’d prayed for.”

I shall restrain myself from describing to you fully how elated I was when I realized the correlation between Betty down in the well and the wolves that were trapped in the hollow so very long ago. Betty is a wolf. A duplicitous, scheming, nasty girl with a sadistic streak a mile wide. The kind of girl who would be more than willing to slit the throat of an innocent boy for sport. She’s a lone wolf, though she does find a mate/co-conspirator of sorts. Early in the book, Wolk foreshadows all of this. In a conversation with her grandfather, Annabelle asks if, when you raised it right, a wolf could become a dog. “A wolf is not a dog and never will be . . . no matter how you raise it.” Of course you might call Toby a lone wolf as well. He doesn’t seek out the company of other people and, like a wolf, he’s shot down for looking like a threat.

What Wolk manages to do is play with the reader’s desire for righteous justice. Sure Annabelle feels conflicted about Betty’s fate in the will but will young readers? There is no doubt in my mind that young readers in bookclubs everywhere will have a hard time feeling as bad for the antagonist’s fate as Annabelle does. Even at death’s door, the girl manages the twist the knife into Toby one last time. I can easily see kids in bookclub’s saying, “Sure, it must be awful to be impaled in a well for days on end . . . . buuuut . . . .” Wolk may have done too good a job delving deep into Betty’s dark side. It almost becomes a question of grace. We’re not even talking about forgiveness here. Can you just feel bad about what’s happened to the girl, even if it hasn’t changed her personality and even if she’s still awful? Wolk might have discussed after Betty’s death the details of her family situation, but she chooses not to. She isn’t making it easy for us. Betty lives and dies a terrible human being, yet oddly we’re the ones left with the consequences of that.

In talking with other people about the book, some have commented about what it a relief it was that Betty didn’t turn into a sweet little angel after her accident. This is true, but there is also no time. There will never be any redemption for Betty Glengarry. We don’t learn any specific details about her unhappy home life or what it was that turned her into the pint-sized monster she is. And her death comes in that quiet, unexpected way that so many deaths do come to us. Out of the blue and with a whisper. For all that she spent time in the well, she lies until her very last breath about how she got there. It’s like the novel Atonement with its young liar, but without the actual atoning.

Wolk says she wrote this book and based much of it on her own family’s stories. Her memories provided a great deal of the information because, as she says, even the simplest life on a Pennsylvanian farm can yield stories, all thanks to a child’s perspective. There will be people who compare it to To Kill a Mockingbird but to my mind it bears more in common with The Crucible. So much of the book examines how we judge as a society and how that judgment can grow out of hand (the fact that both this book and Miller’s play pivot on the false testimony of young girls is not insignificant). Now I’ll tell you the real reason I flipped to the back of the book early. With Wolf Hollow Wolk threatens child readers with injustice. As you read, there is a very great chance that Betty’s lies will carry the day and that she’ll never be held accountable for her actions. It doesn’t work out that way, though the ending isn’t what you’d call triumphant for Annabelle either. It’s all complicated, but it was that unknowing midway through the book that made me need to see where everything was going. In this book there are pieces to pick apart about lying, truth, the greater good, minority vs. majority opinions, the price of honesty and more. For that reason, I think it very likely it’ll find itself in good standing for a long time to come. A book unafraid to be uneasy.

On shelves now.

Source: Thanks to Penguin Random House for passing on the galley.

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 4/13/2016

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reviews,

middle grade fiction,

Best Books,

Candlewick,

Kate DiCamillo,

middle grade historical fiction,

middle grade realistic fiction,

Best Books of 2016,

2016 reviews,

Reviews 2016,

2016 middle grade fiction,

2017 Newbery contenders,

2016 middle grade historical fiction,

Add a tag

Raymie Nightingale

Raymie Nightingale

By Kate DiCamillo

Candlewick Press

$16.99

ISBN: 978-0-7636-8117-3

Ages 9-12

On shelves now

My relationship to Kate DiCamillo’s books is one built entirely on meaning. Which is to say, the less emotional and meaningful they are, the better I like ‘em. Spaghetti loving horses and girls that live in tree houses? Right up my alley! China rabbits and mice with excessive earlobes? Not my cup of tea. It’s good as a reviewer to know your own shortcomings and I just sort of figured that I’d avoid DiCamillo books when they looked deep and insightful. And when the cover for Raymie Nightingale was released it was easily summarized in one word: Meaningful. A girl, seen from behind, stands ankle-deep in water holding a single baton. Still, I’ve had a good run of luck with DiCamillo as of late and I was willing to push it. I polled my friends who had read the book. The poor souls had to answer the impossible question, “Will I like it?” but they shouldered the burden bravely. Yes, they said. I would like it. I read it. And you know what? I do like it! It is, without a doubt, one of the saddest books I’ve ever read, but I like it a lot. I like the wordplay, the characters, and the setting. I like what the book has to say about friendship and being honest with yourself and others. I like the ending very very much indeed (it has a killer climax that I feel like I should have seen coming, but didn’t). I do think it’s a different kind of DiCamillo book than folks are used to. It’s her style, no bones about it, but coming from a deeper place than her books have in the past. In any case, it’s a keeper. Meaning plus pep.

Maybe it isn’t much of a plan, but don’t tell Raymie that. So far she thinks she has it all figured out. Since her father skipped town with that dental hygienist, things haven’t been right in Raymie’s world. The best thing to do would be to get her father back, so she comes up with what surely must be a sure-fire plan. She’ll just learn how to throw a baton, enter the Little Miss Central Florida Tire competition, win, and when her father sees her picture in the paper he’ll come on home and all will be well. Trouble (or deliverance) comes in the form of Louisiana and Beverly, the two other girls who are taking this class with Ida Nee (the baton-twirling instructor). Unexpectedly, the three girls become friends and set about to solve one another’s problems. Whether it’s retrieving library books from scary nursing home rooms, saving cats, or even lives, these three rancheros have each other’s backs just when they need them most.

DiCamillo has grown as an author over the years. So much so that when she begins Raymie Nightingale she dives right into the story. She’s trusting her child readers to not only stick with what she’s putting down, but to decipher it as well. As a result, some of them are going to experience some confusion right at the tale’s beginning. A strange girl seemingly faints, moaning about betrayal in front of a high-strung baton instructor. Our heroine stands impressed and almost envious. Then we learn about Raymie’s father and the whole enterprise takes a little while to coalesce. It’s a gutsy choice. I suspect that debut authors in general would eschew beginning their books in this way. A pity, since it grabs your attention by an act of simple befuddlement.

Initial befuddlement isn’t enough to keep you going, though. You need a hook to sustain you. And in a book like this, you find that the characters are what stay with you the longest. Raymie in particular. It isn’t just about identification. The kid reading this book is going to impress on Raymie like baby birds impress on sock puppet mamas. She’s like Fone Bone in Jeff Smith’s series. She’s simultaneously a mere outline of a character and a fully fleshed out human being. Still, she’s an avatar for readers. We see things through her rather than with her. And sure, her name is also the title, but names are almost always titles for Kate DiCamillo (exceptions being The Magician’s Elephant, The Tiger Rising, and that Christmas picture book, of course). If you’re anything like me, you’re willing to follow the characters into absurdity and back. When Beverly says of her mother that, “Now she’s just someone who works in the Belknap Tower gift shop selling canned sunshine and rubber alligators” you go with it. You don’t even blink. The setting is almost a character as well. I suspect DiCamillo’s been away from Florida too long. Not in her travels, but in her books. Children’s authors that willingly choose to set their books in the Sunshine State do so for very personal reasons. DiCamillo’s Florida is vastly different from that of Carl Hiaasen’s, for example. It’s a Florida where class exists and is something that permeates everything. Few authors dare to consider lower or lower middle classes, but it’s one of the things I’ve always respected about DiCamillo in general.

Whenever I write a review for a book I play around with the different paragraphs. Should I mention that the book is sad at the beginning of the review or at the end? Where do I put my theory about historical fiction? Should character development be after the plot description paragraph or further in? But when it comes to those written lines I really liked in a book, that kind of stuff shouldn’t have to wait. For example, I adore the lines, “There was something scary about watching an adult sleep. It was as if no one at all were in charge of the world.” DiCamillo excels in the most peculiar of details. One particular favorite was the small paper cups with red riddles on their sides. The Elephantes got them for free because they were misprinted without answers. It’s my secret hope that when DiCamillo does school visits for this book she’ll ask the kids in the audience what the answer to the riddle, “What has three legs, no arms, and reads the paper all day long?” might be. It’s her version of “Why is a raven like a writing desk?”

Now let us discuss a genre: Historical fiction. One question. Why? Not “Why does it exist?” but rather “Why should any novel for kids be historical?” The easy answer is that when you write historical fiction you have built in, legitimate drama. The waters rise during Hurricane Katrina or San Francisco’s on fire. But this idea doesn’t apply to small, quiet novels like Raymie Nightingale. Set in the summer of 1975, there are only the barest of nods to the time period. Sometimes authors do this when the book is semi-autobiographical, as with Jenni Holm’s Sunny Side Up. Since this novel is set in Central Florida and DiCamillo grew up there, there’s a chance that she’s using the setting to draw inspiration for the tale. The third reason authors sometimes set books in the past is that it frees them up from the restrictions of the internet and cell phone (a.k.a. guaranteed plot killers). Yet nothing that happens in Raymie Nightingale requires that cell phones remain a thing of the past. The internet is different. Would that all novels could do away with it. Still, in the end I’m not sure that this book necessarily had to be historical. It’s perfectly fine. A decent time period to exist in. Just not particularly required one way or another.

Obviously the book this feels like at first is Because of Winn-Dixie. Girl from a single parent home finds friendship and (later rather than sooner, in the case of Raymie Nightingale) an incredibly ugly dog. But what surprised me about Raymie was that this really felt more like Winn-Dixie drenched in sadness. Sadness is important to DiCamillo. As an author, she’s best able to draw out her characters and their wants if there’s something lost inside of them that needs to be found. In this case, it’s Raymie’s father, the schmuck who took off with his dental hygienist. Of course all the characters are sad in different ways here. About the time you run across the sinkhole (the saddest of all watery bodies) on page 235 you’re used to it.

Sure, there are parts of the book I could live without. The parts about Raymie’s soul are superfluous. The storyline of Isabelle and the nursing home isn’t really resolved. On the flip side, there are lots of other elements within these pages that strike me as fascinating, like for example why the only men in the book are Raymie’s absent father, an absent swimming coach, a librarian, and a janitor. Now when I was a child I avoided sad children’s books like the plague. You know what won the Newbery in the year that I was born? Bridge to Terabithia. And to this day I eschew them at all costs. But though this book is awash in personal tragedies, it’s not a downer. It’s tightly written and full of droll lines and, yes I admit it. It’s meaningful. But the meaning you cull from this book is going to be different for every single reader. Whip smart and infinitely readable, this is DiCamillo at her best. Time to give it a go, folks.

On shelves now.

Source: Final copy sent from publisher for review.

Song to Listen to With This Book: King of the Road

Alternative Song: I Wanna Hold Your Hand

Like This? Then Try:

Five Children on the Western Front

Five Children on the Western Front

Read this aloud to my 4th graders last year with great success. I did so because one child had read Five Children and It and pestered me to read this one aloud so I did. But none of the others had nor did they have any desire to after I read this one. This year one of my fourth graders read it and loved it. She did take Five Children and It to read afterwards, but seems to have lost steam with it. So I think this works just fine without familiarity with the earlier books. I suggest giving it to those who like The War That Saved My Life.

Just read this (I’d loved the earlier books as a child). I thought the author did a terrific job, balancing the lightness and fantasy of the story with the waste and bleakness of war–handling it in a deft way for the age group. Definitely worth reading.