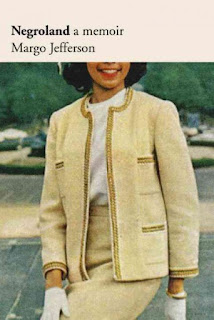

Negroland: a memoir by Margo Jefferson 2015

Pantheon/Knopf Doubleday

IQ "Average American women were killed like this [by men in crimes of passion] every day. But we weren't raised to be average women; we were raised to be better than most women of either race. White women, our mothers reminded us pointedly, could afford more of these casualties. There were more of them, weren't there? There were always more white people. There were so few of us, and it had cost so much to construct us. Why were we dying?" 168

There is so much to unpack here, so many quotes I want to discuss, which I will do later on in the review but if you only want to read one paragraph I'll try to make this one tidy.

One sentence review: There is something new to focus on with every reading and like all great works of literature there is something for everyone, the writing is flowery but I mean that in the best way possible.

I fell in love with the life of Margo Jefferson and the history of the Black American elite (think Our Kind of People). I would say I'm on the periphery of the Negroland world so much of what Jefferson describes is vaguely familiar to me but obviously I am not a product of the '50s and '60s so that was all new to me. I appreciated Jefferson's honesty that she finds it difficult to be 100% vulnerable, I imagine that is part of why she chooses to focus so much on the historical. But at least she doesn't pretend that she will bare her soul, but she still manages to go pretty damn far for someone who believes it is easier to write about the sad/racist things. Jefferson eloquently explores the black body, class, Chicago, gender, mental illness and race from when she was a child into adulthood with a touch of dry humor here and there. Jefferson is the epitome of the cool aunt and I want to just sit at her feet everyday and learn (I was fortunate to hear her speak at U of C and it was magical, her voice is heavenly and she's FUNNY).

I understand complaints that the narrative is disjointed but Jefferson always manages to bring her tangents back to the main point. It is not simply random ramblings the author indulges in, each seemingly random thought serves a purpose that connects to the central theme of the chapter/passage. Jefferson does not owe us anything, yes she chose to write a memoir but she also chose to write a social history. She explores some of her flaws and manages to avoid what she so feared; "I think it's too easy to recount unhappy memories when you write about yourself. You bask in your own innocence. You revere your grief. You arrange your angers at their most becoming angles. I don't want this kind of indulgence to dominate my memories" (6). For someone raised to be twice as good and only show off to the benefit of the Black race, Jefferson thankfully manages to let us in on far more than I expected when it comes to the Black elite.

Jefferson comes at my life when she says, "At times I'm impatient with younger blacks who insist they were or would have been better off in black schools, at least from pre-K through middle school. They had, or would have had, a stronger racial and social identity, an identity cleansed of suspicion, subterfuge, confusion, euphemism, presumption, patronization, and disdain. I have no grounds for comparison. The only schools I ever went to were white schools with small numbers of Negroes" (119). I too attended majority white schools and have often wondered if I would have had an easier time identifying with other Black students in college (and even high school) if I had gone to majority Black schools instead of remaining on the periphery. She goes on to explain her impatience because she felt that for the first few years of school she was able to live her life unaware of race and I would agree, there were only a few incidents but mostly I felt free. So she's right, it's a trade off and ultimately we all end up in the same white world. I still think I should have gone to an HBCU just to see what it's like, to force myself to confront my own privilege but I managed to do that at my PWI and there's no point in worrying about it anymore. It's this matter-of-fact tone Jefferson uses throughout the book that I adored, she largely avoids sentimentality. Although she somehow manages to fondly look back at Jack & Jill which makes me sad that I don't share the same happy memories of the group and based on conversations with a few others on Twitter I am not alone in that (someone should research the history of Jack & Jill and explain why it has become so awful although I have my own theory).

Much has already been said about how candidly Jefferson discusses depression, an aspect of mental health that was not discussed in the Black community. Thus I do not wish to dwell on the topic since writers far more articulate than I have mentioned it in their reviews, but I appreciate her talking about it and I know what she means. Slowly but surely the 'strong Black woman' facade is being allowed to crack and we are all the better for it. I wish she had delved a bit into Black women and eating disorders because she mentions how much she loved Ballet and the ideal beauty standards of the Black elite (no big butts or noses for example) but maybe this is not something she witnesses personally. Jefferson mentions that when Thurgood Marshall and Audrey Hepburn died around the same time, she and her friend felt guilty for caring more about Hepburn's death because of all she symbolized for them. At first I raised my eyebrows at this sign of racial disloyalty but she notes what Hepburn meant to her; "And the longing to suffer nothing at all, to be rewarded, decorated, festooned for one's charms and looks, one's piquant daring, one's winning idiosyncrasies: Audrey Hepburn in Funny Face and Breakfast at Tiffany's. Equality in America for a bourgeois black girl meant equal opportunity to be playful and winsome. Indulged" (200). And I understood exactly what she meant. It's why I cling to Beyonce, Carmen Jones (and Dorothy Dandridge by extension), Janelle Monae etc etc. I can't think of a Black manic pixie dream girl but I'd love to have a Black girl play one, to be able to complain about a character we have long been denied.

On Black men & women; "But the boys ruled. We were just aspiring adornments, and how could it be otherwise? The Negro man was at the center of the culture's race obsessions. The Negro woman was on the shabby fringes. She had moments if she was in show business, of course; we craved the erotic command of Tina Turner, the arch insolence of Diana Ross, the melismatic authenticity of Aretha. But in life, when a Good Negro Girl attached herself to a ghetto boy hoping to go street and compensate for her bourgeois privilege, if she didn't get killed with or by him, she usually lived to become a socially disdained, financially disabled black woman destined to produce at least one baby she would have to care for alone. What was the matter with us? Were we plagued by some monstrous need, some vestigial longing to plunge back into the abyss Negros had been consigned to for centuries? Was this some variant of survivor guilt? No, that phrase is too generic. I'd call it the guilty confusion of those who were raised to defiantly accept their entitlement. To be more than survivors, to be victors who knew that victory was as much a threat as failure, and could be turned against them at any moment" (169). Jefferson embraces feminism and pushes back on the constraints of Black womanhood.

I've already picked this book up and re-read random passages which is rare for me so soon after finishing it the first time (this is what happens when you have a towering TBR pile). I took an African American Autobiography class in college and I really hope this book gets added to the syllabus. It combines so many topics of interest to me, acknowledges so many greats in Black history, exposes some secrets of the Black upper class (passing, brown paper bag test) while combining history and memoir, absolutely captivating. I instinctively knew I would need to buy this book (ended up getting it autographed) and I am so glad I did. The cover is phenomenal.

0 Comments on Negroland as of 1/1/1900

Add a Comment