new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Virgil, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 7 of 7

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Virgil in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Hannah Charters,

on 10/12/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

horace,

Virgil,

ovid,

Ancient Rome,

*Featured,

catullus,

Classics & Archaeology,

Oxford Scholarly Editions Online,

Online products,

OSEO,

Quizzes & Polls,

Classical Latin,

latin poetry,

hannah charters,

Arts & Humanities,

OSEO classics,

Add a tag

The shadow of the Roman poets falls right across the entire western literary tradition: from Vergil’s Aeneid, about the fall of Troy, the wooden horse, and the founding of Rome; through the great love poets, Catullus, Propertius, and Tibullus; Ovid’s Metamorphoses, treasure-house of myth for the Renaissance and Shakespeare; to Horace’s Dulce et decorum est, echoing through the twentieth century. We all take it for granted … so now’s the time to check your working.

The post Can you get X out of X in our Latin poetry quiz? appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Eleanor Jackson,

on 6/18/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

History,

Literature,

Europe,

Vesuvius,

Virgil,

Naples,

Homer,

Odysseus,

siren,

*Featured,

Art & Architecture,

Classics & Archaeology,

romulus augustulus,

Arts & Humanities,

Claudio Buongiovanni,

Jessica Hughes,

Lucius Cocceius Auctus,

Parthenope,

Remembering Parthenope,

Saint Janarius,

The Reception of Classical Naples from Antiquity to the Present,

Tiberius Julius Tarsos,

Add a tag

The city that we now call Naples began life in the seventh century BC, when Euboean colonists from the town of Cumae founded a small settlement on the rocky headland of Pizzofalcone. This settlement was christened 'Parthenope' after the mythical siren whose corpse had supposedly been discovered there, but it soon became known as Palaepolis ('Old City'), after a Neapolis ('New City') was founded close by.

The post Six people who helped make ancient Naples great appeared first on OUPblog.

By: KatherineS,

on 11/8/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

reading list,

OWC,

Saint Augustine,

Oxford World's Classics,

cicero,

Virgil,

ovid,

*Featured,

Classics & Archaeology,

livy,

Lucretius,

Marcus Aurelius,

aeneid,

Tacitus,

Judith Luna,

Georgics,

metamorphoses,

Roman Literature,

The Rise of Rome,

Literature,

Add a tag

Roman literature often derived from Greek sources, but took Greek models and made them its own. It includes some of the best known classical authors such as Ovid and Virgil, as well as a Roman emperor who found time to write down his philosophical reflections.

Saint Augustine’s Confessions by Saint Augustine

Augustine was a gifted teacher who abandoned his secular career and eventually became bishop of Hippo. His Confessions are a remarkable record of his wrestlings to accept his faith, his struggles to overcome sexual desire and renounce marriage and ambition. His final moment of conversion in a Milan garden is deeply moving.

On Obligations by Cicero

The great Roman statesman Cicero lived at the center of power. He was an advocate and orator as well as philosopher, who met his death bravely at the hands of Mark Antony’s executioners. On Obligations was written after the assassination of Julius Caesar to provide principles of behavior for aspiring politicians. Exploring as it does the tensions between honorable conduct and expediency in public life, it should be recommended reading for all public servants.

The Rise of Rome by Livy

The Roman historian Livy wrote a massive history of Rome in 142 books, of which only 35 survive in their entirety. In the first five books, translated here, he covers the period from Rome’s beginnings to her first major defeat, by the Gauls, in 390 BC. Among the many stories he includes are Romulus and Remus, the rape of Lucretia, Horatius at the bridge, and Cincinnatus called from his farm to save the state.

On the Nature of the Universe by Lucretius

Lucretius lived during the collapse of the Roman republic, and his poem De rerum natura sets out to relieve men of a fear of death. He argues that the world and everything in it are governed by the laws of nature, not by the gods, and the soul cannot be punished after death because it is mortal, and dies with the body. The book is an astonishing mix of scientific treatise, moral tract, and wonderful poetry.

Meditations by Marcus Aurelius

Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius was probably on military campaign in Germany when he wrote his philosophical reflections in a private notebook. Drawing on Stoic teachings, particularly those of Epictetus, Marcus tried to summarize the principles by which he led his life, to help to make sense of death and to look for moral significance in the natural world. Intimate writings, they bring us close to the personality of the emperor, who is often disillusioned with his own status, and with human life in general.

Metamorphoses by Ovid

The Metamorphoses is a wonderful collection of legendary stories and myth, often involving transformation, beginning with the transformation of Chaos into an ordered universe. In witty and elegant verse Ovid narrates the stories of Echo and Narcissus, Pyramus and Thisbe, Perseus and Andromeda, the rape of Proserpine, Orpheus and Eurydice, and many more.

Agricola and Germany by Tacitus

Tacitus is perhaps best known for the Histories and the Annals, an account of life under emperors Tiberius, Claudius and Nero. The shorter Agricola and Germany consist of a life of his father-in-law, who completed the conquest of Britain, and an account of Rome’s most dangerous enemies, the Germans. They are fascinating accounts of the two countries and their people, the northern ‘barbarians’. Later, German nationalists attempted to appropriate Germania in support of National Socialist racial ideas.

Georgics by Virgil

The Georgics is a poem of celebration for the land and the farmer’s life. Virgil doesn’t romanticize, rather he describes the setbacks as well as the rewards of working the land, and provides memorable descriptions of vine and olive cultivation, raising crops, and bee-keeping. It is both a practical agricultural manual and allegory, and brings the ancient rural world vividly to life.

Aeneid by Virgil

The story of Aeneas’ seven-year journey from the ruins of Troy to Italy, where he becomes the founding ancestor of Rome, is a narrative on an epic scale. Not only do Aeneas and his companions have to contend with the natural elements, they are at the whim of the gods and goddesses who hamper and assist them. It tells of Aeneas’ love affair with Dido of Carthage and of Aeneas’ encounters with the Harpies and the Cumaean Sibyl, and his adventures in the Underworld.

Heading image: Roman Virgil Folio. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post A reading list of Roman classics appeared first on OUPblog.

By: PennyF,

on 11/6/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Literature,

Philosophy,

herodotus,

Caesar,

Plato,

cicero,

Virgil,

Infographics,

Sappho,

Homer,

*Featured,

Images & Slideshows,

Classics & Archaeology,

Arts & Humanities,

ancient authors,

Ancient Ideas for Modern Times,

ancient literature,

ancient philosophy,

Christopher Pelling,

Twelve Voices from Greece and Rome,

Add a tag

The ancient writers of Greece and Rome are familiar to many, but what do their voices really tell us about who they were and what they believed? In Twelve Voices from Greece and Rome, Christopher Pelling and Maria Wyke provide a vibrant and distinctive introduction to twelve of the greatest authors from ancient Greece and Rome, writers whose voices still resonate across the centuries. Below is an infographic that shows how each of the great classical authors would describe their voice today, if they could.

Download the infographic in pdf or jpeg.

Featured image credit: “Exterior of the Colosseum” by Diana Ringo. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Ancient voices for today [infographic] appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Kirsty,

on 5/26/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Literature,

classics,

Journals,

Russia,

Virgil,

Humanities,

*Featured,

oxford journals,

Classics & Archaeology,

classical literature,

roman poetry,

Classical Receptions Journal,

latin poetry,

russian translation of virgil,

the aeneid,

virgilian,

Add a tag

By Zara Martirosova Torlone

In 1979 one of the most prominent Russian classical scholars of the later part of the twentienth century, Mikhail Gasparov stated: “Virgil did not have much luck in Russia: they neither knew nor loved him . . .”. This lack of interest in Virgil on Russian soil Gasparov mostly blamed on the absence of canonical Russian translations of Virgil, especially the Aeneid. There have been several attempts at translating the Roman epic into Russian, four of them most notable and significant. In the 18th century Vasilii Petrov (1730-1778), the court poet of Catherine the Great was the first poet to undertake this monumental task. His translation, however, although highly praised by Catherine and the newly established Russian Academy, was ridiculed by the educated elite as a feeble shadow of the great Roman poem. Another attempt at translating the whole epic did not happen until late nineteenth century and was undertaken by a prominent Russian poet Afanasii Fet (1820-1892) who together with a Russian philosopher Vladimir Solov’ev (1853-1900) attempted to finally bring the Aeneid to the Russian reading public. While this translation was received much more favorably, it still did not acquire the desired canonical status. Valerii Briusov (1873-1924), one of the founders of Russian Symbolism and an accomplished translator, devoted most of his life to yet another translation of the Aeneid, but also fell short of the mark because the final version of his translation exhibited many ‘foreignizing’ tendencies replete with incomprehensible Latinisms, which rendered the text almost unreadable. Sergei Osherov (1931-1983), a Russian classical scholar, who undertook another translation during the era of ‘socialist realism’ took a more liberal approach to the Virgilian text, one that rendered it significanltly more readable by a wider audience but steered away from the poetic intricacies and complexity of the Latin text.

This is the situation Gasparov was referrring to when alluding the failure of Virgil to provoke interest in Russian reading public. And yet the importance of Virgil for the formation of Russian literary identity remained consistent as Russian writers partcipated in building their national literary canon.

Russian consciousness formed its connection to Rome and thus to Virgil through two venues: one was through the great but pagan Roman empire – that was the political claim that entailed imperial power and expansion. Another was via Byzantine Rome and the piety associated with its Orthodoxy. Even Catherine the Great who prided herself on her secularism and association with Voltaire and Montesquieu, had in mind the leadership of Russia as the religious and political ideal of a unified ecumenical Orthodoxy under which all the Orthodox East would be politically united.

Virgil came to be seen as the answer to both discourses and to encompass both the imperial rhetoric and the spiritual quest for a Russian Christian soul.

The eighteenth century Virgilian reception was mainly concerned with the imperial aspirations as the initial reaction to the text of the Aeneid in Russian literature. Antiokh Kantemir’s (1708-1744), Mikhailo Lomonosov’s (1711-1765), and Nikolai Kheraskov’s (1733-1807) failed attempts at a national heroic epic were encouraged by the Russian ruling family but failed to elicit any interest in the reading public. In the same way Vasilii Petrov’s first unfortunate translation of the Aeneid reflected the tendency to glorify and idealize the ruling monarch as a way to promote national pride but was found lacking in adequately reflecting the poetic genius of Virgil in Russian.

As Russian literary figures of the eighteenth century were experimenting with different approaches to a national epic, there emerged a quite influential and popular genre of travesitied epics. In opposition to the courtly attempts to glorify the house of the Romanovs through Virgilian reception, Nikolai Osipov wrote his burlesque Aeneid Turned Upside Down (1791-6) where following the European examples of French Paul Scarron and German Aloys Blumauer he made Aeneas speak the base language of the Russian everyday man and cast his adventures in a less than heroic light.

Epic, however, was not the only genre through which Russian literati tried to bringVirgil to Russia. As with the most European receptions of the Aeneid, the tragic pathos of Dido’s love and suicide attracted attention already in the eighteenth century at the same time with the epics. Iakov Kniazhnin’s ((1758-1815) play Dido (1769), which stands at the very beginnings of Russian mythological tragedy, offered his readers an unusual and politicized interpretation of Book 4 of the Aeneid combined with French and Italian influences on his Virgilian reception.

With Alexander Pushkin (1799-1837) Russian literature entered yet another stage of Virgilian reception. The courtly literature was long forgotten and so were the monumental attempts at epic grandeur. Pushkin refrained from any open allusion to or evocation of Virgil limiting them usually to a few passing jokes. Instead he penned his own diminutive epic of national pride, the Bronze Horseman in which he conteplated the same issues pondered by Virgil two thousand years earlier. At the center of his poem is the confrontation between the man and a state, individual happiness and civic duty, which Pushkin approaches in ways familiar to the readers of Virgil.

While the connection of Virgilian reception with Russia’s ‘messianic’ Orthodox mission manifested itself intermittently in secular court literature and even in Petrov’s translation, the specific and pointedly deliberate articulation of that mission occured in the literature at the beginning of the twentieth century and is represented by such formative thinkers as Vladimir Solov’ev (1853-1900), Viacheslav Ivanov (1866-1949), and Georgii Fedotov (1886-1951), who saw Virgil in messianic and prophetic light and as the source of answers for Russian spiritual quest both at home and abroad.

With Joseph Brodsky (1940-1996) the Russian Virgil entered the stage of post-modernism. Brodsky’s Virgilian allusions are numerous and persist in Brodsky’s poetics through its entire evolution. However, the monumental themes of either imperial pride or messianic mission become replaced in Brodsky by simpler, mundane, and even base themes. Brodsky reshaped Virgil’s Arcadia into a snow covered terrain and his Aeneas is a man tormented by the brutalizing price of his heroic destiny. As Brodsky reconfigured different episodes from the Virgilian texts through the lyric prism of human emotion, Virgil remained a constant presence both in his poetry and his essays as the poet moved with ease between ancient and modern, between emotion and detachment, between Russian and English, providing a remarkable closure to the Russian Virgil in the twentieth century.

Zara Martirosova Torlone is an Associate Professor of Classics and on the Core Faculty at the Havighurst Center for Russian and Post-Soviet Studies at Miami University (Ohio, USA). She received her B.A. from Moscow State University, Russia and her Ph.D. from Columbia University in New York. Her publications include Russia and the Classics: Poetry’s Foreign Muse (2009) and Vergil in Russia: National Identity and Classical Reception (2014). She has edited a special issue of Classical Receptions Journal, entitled ‘Classical Reception in Eastern and Central Europe’ to which she also contributed an essay on Joseph Brodsky’s reception of Virgil’s Eclogues.

Classical Receptions Journal covers all aspects of the reception of the texts and material culture of ancient Greece and Rome from antiquity to the present day. It aims to explore the relationships between transmission, interpretation, translation, transplantation, rewriting, redesigning and rethinking of Greek and Roman material in other contexts and cultures. It addresses the implications both for the receiving contexts and for the ancient, and compares different types of linguistic, textual and ideological interactions.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only classics and archaeology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Virgil in Russia appeared first on OUPblog.

By: LaurenH,

on 5/2/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Roman,

horace,

Latin,

Virgil,

Humanities,

J. C. McKeown,

*Featured,

Classics & Archaeology,

9/11 memorial,

aeneid,

Cabinet of Greek Curiosities,

Cabinet of Roman Curiosities,

Classical Latin,

national memorials,

Oxford Anthology of Roman Literature,

september 11 memorial,

classics,

Add a tag

By J. C. McKeown

The National September 11 Memorial Museum will be opened in a few weeks. On the otherwise starkly bare wall at the entrance is a 60-foot-long inscription in 15-inch letters made from steel salvaged from the twin towers: NO DAY SHALL ERASE YOU FROM THE MEMORY OF TIME. This noble sentiment is a quotation from Virgil’s Aeneid, one of mankind’s highest literary achievements, but its appropriateness has been questioned. In the context of the Aeneid, Virgil is commemorating a homosexual pair of warriors killed while making a bloody surprise attack on their sleeping enemies’ camp. Three years ago, an article in the New York Times suggested that “anyone troubling to take even a cursory glance at the quotation’s context will find the choice offers neither instruction nor solace.” But the museum was unmoved by such objections, and its director has recently defended the choice, asserting, perhaps rather cryptically, that the quotation characterizes the “museum’s overall commemorative context.”

It is unfortunate that this controversy has arisen, especially since so few people nowadays know about the context of the quote in the Aeneid. Those who lost family members or friends in the attacks should not have their thoughts and feelings distracted in this way. The sentiments expressed on national monuments aim to be strongly and unambiguously assertive of a view held by the whole community, but perhaps they are inherently vulnerable to controversial interpretations. Ideally, of course, such quotations should resonate more deeply than the meaning of the actual words, but would it not be best to accept the obviously sincere intentions of the museum’s committee and let the matter drop?

“It is sweet and fitting to die for one’s country” in classical Greek on a memorial honoring the dead in the First Balkan War. Credit: J.C. McKeown

Otherwise, where will it end? Should we hesitate about using dulce et decorum est pro patria mori (“It is sweet and fitting to die for one’s country”), a line by Horace, Virgil’s contemporary, found so often on war memorials? In the 1910s, it was inscribed at Arlington and at Sandhurst, the British military academy, and was even translated into classical Greek (mirabile dictu!) on a memorial honoring the dead in the First Balkan War.

Before the decade was out, however, in the most celebrated of all World War I poems, Wilfred Owen had described Horace’s line as “the old lie.” Horace’s own authority to voice such ideals may be questioned. He was writing a poem of national significance–it is one of his “Roman Odes”–but the very next line, “death pursues even the man who runs away,” might make us recall a different poem in which Horace rather flippantly admits that he had thrown away his shield and fled at the Battle of Philippi. These considerations may give us pause for thought, but the validity of dulce et decorum in a national context is not diminished.

Carpe diem is perhaps the most ubiquitous of all Latin tags, but few people are aware of its original use: Horace is trying to persuade a girl to sleep with him. In another quote from the same book of Odes, Horace assures us that a person who is integer vitae scelerisque purus (“He who lives an unblemished life and is not tainted with crime”) is under divine protection, but the poem is essentially trivial, for Horace’s guardian deity turns out to be Cupid, who keeps wolves at bay while he sings in the woods about his mistress; even so, the poem was sung for centuries at Swedish funerals.

The fundamental democratic principles of equality and unity encapsulated so precisely in e pluribus unum are surely not diminished by the possibility that it was inspired by a phrase from an inconsequential poem attributed to Virgil: color est e pluribus unus (“from being several, the color is one”), in a description of an old peasant grinding the various ingredients together to make a vegetable pâté for his breakfast.

We have difficulties enough with the nuances of our own language. How many of those who wear T-shirts emblazoned with The Road Not Taken regard Frost’s best known poem not so much as a declaration of their free spirit, but rather as “that cunning nugget of nihilism disguised as an anthem for nonconformity” (New Yorker, 10 February 2014)?

Even Virgil himself has been charged with quoting inappropriately. When Aeneas stammers to Dido’s ghost in the Underworld, invitus, regina, tuo de litore cessi (“unwillingly, O queen, I left your shore”), it is an undoubted echo of Catullus’s translation of an elegant Hellenistic court poem, in which a lock of Queen Berenice’s hair laments that it is now a constellation, no longer with the queen: invita, o regina, tuo de vertice cessi (“unwillingly, O queen, I left your head”). To quote the standard commentary on Virgil’s line: “modern susceptibilities are pained by Virgil’s presumed indifference to the incongruity so produced.”

Aeneas tells Dido the misfortunes of the Trojan city. Oil on canvas, 1815. Pierre-Narcisse Guérin, The Louvre. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

There is classical precedent for changing a memorial inscription. After the Greek victory over the Persians at Plataea in 479 BC, the Greek commander set up an inscription at Delphi: “Pausanias, leader of the Greeks, when he destroyed the army of the Persians, dedicated this memorial to Apollo.” He was ordered to remove it, and told he could put it up again when he had defeated the Persians single-handedly. Might that be the best solution to all this controversy? The task of re-writing the inscription might be given to Billy Collins, who was Poet Laureate at the time of the attacks. He would be sure to resist those who want to:

“tie the poem to a chair with rope

and torture a confession out of it.

They begin beating it with a hose

to find out what it really means.”

J. C. McKeown is Professor of Classics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, co-editor of the Oxford Anthology of Roman Literature, and author of A Cabinet of Greek Curiosities, A Cabinet of Roman Curiosities, and Classical Latin: An Introductory Course.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only classics and archaeology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The 9/11 memorial and the Aeneid: misappropriation or sincere sentiment? appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alice,

on 2/17/2012

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

digitization,

text,

Virgil,

antiquity,

Humanities,

tablets,

Social Sciences,

*Featured,

scholarly editions,

Andrew Zurcher,

Edmund Spenser,

Mantuan,

Marot,

Oxford Scholarly Editions Online,

Shepheardes Calender,

Theocritus,

thenot,

calender,

cuddie,

shepheardes,

eclogues,

Literature,

Education,

Add a tag

By Andrew Zurcher

The “Februarie” eclogue of Edmund Spenser’s pastoral collection, The Shepheardes Calender, was first published in 1579. It presents a conversation between two shepherds, a brash “Heardmans boye” called Cuddie and an old stick-in-the-mud named Thenot. The two of them meet on a cold winter day and get into an argument about age: Cuddie thinks Thenot is a wasted and weak-kneed whinger, while Thenot blames Cuddie for his heedless and slightly arrogant headstrongness. To support his position, Thenot tells a moralising tale about an ambitious young briar and a hoary oak. In his eagerness to flaunt his brave blooms full in the sun, the briar persuades a local husbandman to chop down the mossy tree; but the end of the tale turns bitter for the little plant when, deprived of the sheltering support of his onetime neighbour, he is utterly blown away in a heavy gale. Thenot is in the middle of applying the moral of his tale when Cuddie interrupts, and leaves in a huff – petulant and dismissive to the last. As the eclogue breaks off, the reader is caught in an old-fashioned and hackneyed dilemma: is it better to embrace the beautiful but rootless new, or cling to the solid, gnarled old?

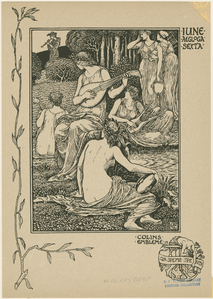

June Aegloga Sexta. Source: New York Public Library.

poses this gnarled horn of a problem in the middle of a printed book that, itself, has already begun to play in a very material way with the tensions between antiquity and

newfangleness. Spenser’s eclogues are conspicuously modeled on those of

Theocritus and

Virgil,

Marot and

Mantuan. The poems were first published elaborated with E.K.’s prefaces, his introductions (or “Arguments”) to each of the twelve

“aeglogae,” and his explanatory notes. These annotations are presented in a Roman type that contrasts visually with the black letter of Spenser’s poetry, framing it in a style that emulated early modern editions of Virgil’s eclogues, as well as the theological and legal texts that, in this humanist period, were often produced entirely engulfed in glosses and comments. Each of the eclogues is also accompanied by a woodcut, done in a rough style, and concludes with an “embleme” apiece for each of the eclogue’s interlocutors. These archaising features belie the novelty of Spenser’s project – the first complete set of original pastoral poems in English, and a collection that, in its allegorical engagement with the history of England’s recent and successive reformations, put this country and its fledgling literary culture on the map. Here at last was England’s Virgil, said Spenser himself. Just look at his book. But is it an old book, or a new book? Is it new-old, or old-new? What is the meaning of the new, if it be not interpreted by the old?

One of the most exciting aspects digitizing works such as in the Oxford Scholarly Editions Online (OSEO) project is