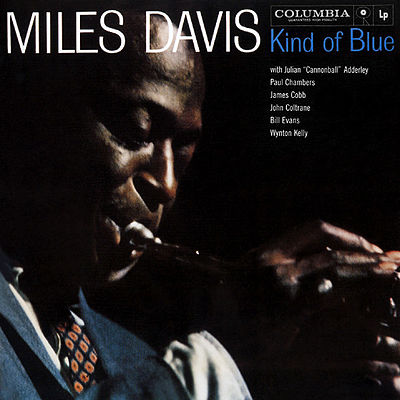

What is a classic album? Not a classical album – a classic album. One definition would be a recording that is both of superb quality and of enduring significance. I would suggest that Miles Davis’s 1959 recording Kind of Blue is indubitably a classic. It presents music making of the highest order, and it has influenced — and continues to influence — jazz to this day.

There were several important records released in 1959, but no event or recording matches the importance of the release of the new Miles Davis album Kind of Blue on 17 August 1959. There were people waiting in line at record stores to buy it on the day it appeared. It sold very well from its first day, and it has sold increasingly well ever since. It is the best-selling jazz album in the Columbia Records catalogue, and at the end of the twentieth century it was voted one of the ten best albums ever produced.

But popularity or commercial success do not correlate with musical worth, and it is in the music on the recording that we find both quality and significance. From the very first notes we know we are hearing something new. Piano and bass draw in the listener into a new world of sound: contemplative, dreamy and yet intense.

The pianist here is Bill Evans, who was new to Davis’s band and a vital contributor to the whole project. Evans played spaciously and had an advanced harmonic sense. His sound was floating and open. The lighter sound and less crowded manner were more akin to the understated way in which Davis himself played. “He plays the piano the way it should be played,” said Davis about Bill Evans. And although Davis’s speech was often sprinkled with blunt Anglo-Saxon expressions, he waxed poetic about Evans’s playing: “Bill had this quiet fire. . . . [T]he sound he got was like crystal notes or sparkling water cascading down from some clear waterfall.” The admiration was mutual. Evans thought of Davis and the other musicians in his band as “superhumans.”

Evans makes his mark throughout the album, though Wynton Kelly substitutes for him on the bluesier and somewhat more traditional second track “Freddie Freeloader.”

Musicians refer to the special sound on Kind of Blue as “modal.” And the term “modal jazz” is often found in writings about jazz styles and jazz history. What exactly is modal jazz? There are two characteristic features that set this style apart. The first is the use of scales that are different from the standard major and minor ones. So the first secret of the special sound on this album is the use of unusual scales. But the second characteristic is even more noticeable, and that is the way the music is grounded on long passages of unchanging harmony. “So What” is an AABA form in which all the A sections are based on a single harmony and the B sections on a different harmony a half step higher.

A [D harmony]

A [D harmony]

B [Eb harmony]

A [D harmony]

Unusual scales are most clearly heard on “All Blues.”

And for hypnotic and meditative, you can’t do better than “Flamenco Sketches,” the last track, which brings the modal conception to its most developed point. It is based upon five scales or modes, and each musician improvises in turn upon all five in order. A clear analysis of this track is given in Mark Gridley’s excellent jazz textbook Jazz Styles.)

An aside here:

It is possible — even likely — that the titles of these two tracks are reversed. In my Musical Quarterly article (link below), I suggest that “Flamenco Sketches” is the correct title for the strumming medium-tempo music on the track that is now known as “All Blues” and that “All Blues” is the correct title for the last, very slow, track on the album. I also show how the mixup occurred in 1959, just as the album was released.

Perhaps the most beautiful piece on the album is the Evans composition “Blue in Green,” for which Coltrane fashions his greatest and most moving solo. Of the five tracks on the album, four are quite long, ranging from nine to eleven and a half minutes, and they are placed two before and two after “Blue in Green.” Regarding the program as a whole, therefore, one sees “Blue in Green” as the small capstone of a musical arch. But “Blue in Green” itself is in arch form, with a palindromic arrangement of the solos. The capstone of this arch upon an arch is the thirty seconds or so of Coltrane’s solo.

Saxophone (Coltrane)

Piano Piano

Trumpet Trumpet

Piano Piano

“Blue in Green”

“Freddie Freeloader” “All Blues”

“So What” “Flamenco Sketches”

Kind of Blue

The great strength of Kind of Blue lies in the consistency of its inspiration and the palpable excitement of its musicians. “See,” wrote Davis in his autobiography, “If you put a musician in a place where he has to do something different from what he does all the time . . . that’s where great art and music happens.”

The post Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue appeared first on OUPblog.