new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Vocation as the Heart of Christian Epistemology, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 4 of 4

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Vocation as the Heart of Christian Epistemology in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: AlyssaB,

on 7/18/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

christianity,

disciple,

trusting,

apostle,

epistemology,

shalom,

Christian Epistemology,

John G. Stackhouse Jr.,

Vocation as the Heart of Christian Epistemology,

stackhouse,

thomas reid,

god—trusting,

infallible,

Books,

Religion,

Humanities,

Need to Know,

*Featured,

scottish enlightenment,

john stackhouse,

Add a tag

This is the final in a four-part series on Christian epistemology titled “Radical faith meets radical doubt: a Christian epistemology for skeptics” by John G. Stackhouse, Jr.

By John G. Stackhouse, Jr.

Do Christians need the kind of radical faith that Thomas Reid, in the Scottish Enlightenment, and Alvin Plantinga, in our own time, offer as the best response to the pervasive skepticism of modernity?

Christians traditionally aver that the Bible gives us infallible truth. But wise Christians also acknowledge that God never promises infallible interpretation to any Christian or group of Christians. The Bible is the Word of God, but any interpretation we render is, unavoidably, an interpretation we render. As such, it is limited by our limitations and flawed by our flaws.

What about the Holy Spirit, then? Doesn’t the very presence of God guarantee truth to the believer? Again, the indwelling of every believer by the Holy Spirit is a precious truth, and the assurance God gives us of his love and care and, yes, guidance thereby is a treasure indeed. But the gift of the Holy Spirit has never entailed that every Christian will score 100% on every math test—or on/in any other test in life, either. Wherever we go—even with the Spirit of God—there we inevitably are.

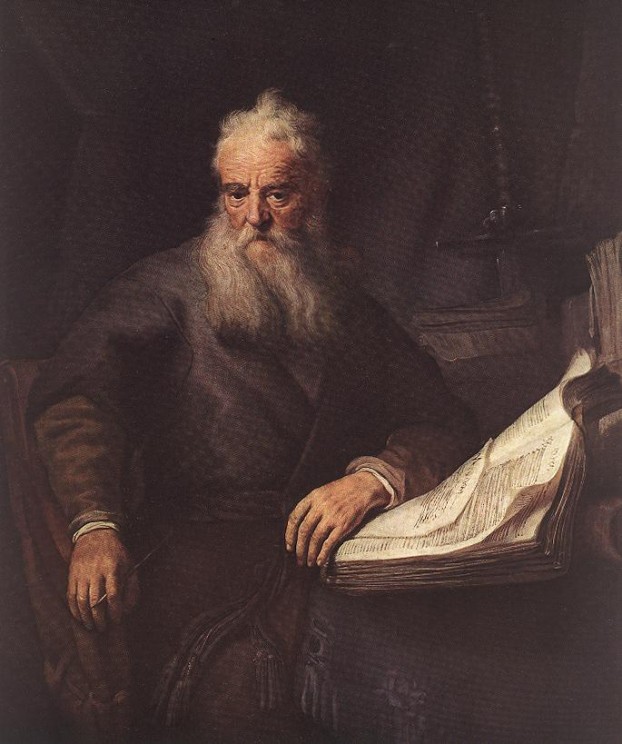

The Apostle Paul comes to our aid at this point and reminds us that we walk by faith, not by sight (II Cor. 5:7), perhaps more profoundly than we knew. We walk, trusting our senses, trusting our memories, trusting our worldviews, and—in the face of all this doubt about all these good, but fallible, gifts of God—trusting God.

The fundamental truth here is that God called humanity to “fill the earth and subdue it, to have dominion” (Gen. 1:28) and to thereby work with him to make the world all it can be. It follows from the fact of this basic commandment that human beings can trust God to give us at least enough knowledge of the world to care for it properly, even as we try faithfully to keep learning more about it so we can care for it better.

Similarly, God called the Christian Church to “make disciples of all nations” (Matt. 28:19), and to thereby work with God to help humanity become all we can be. It likewise follows that we Christians can trust God to give us at least enough knowledge of ourselves and our fellow human beings to disciple each other properly, even as we try faithfully to learn more about ourselves and God so we can disciple each other better.

More particularly, God calls particular groups of people and particular individuals to particular ways of making shalom and making disciples. Modern societies feature such diverse elements as the various parts and forms of the state, the family, businesses, schools, health care facilities, churches, missionary agencies, mass entertainment and news media, and so on. These various instances of shalom-making and disciple-making have particular ways of knowing, and particular bodies of knowledge, that are best suited to the fulfillment of their mission. Again, then, God can be trusted to provide these institutions and individuals distinctively what they need, including what they need epistemically, to fulfill their callings.

So we can and should rejoice in the gracious providence of God, who always supplies our needs in order for us to fulfill God’s call upon our lives. God gives us, as we pray, “our daily bread”—in metaphorical terms of knowledge as well as in literal terms of nourishment.

At the same time, the Bible’s depiction of human limitations squares nicely with the history of skeptical philosophy, and prompts us to be humble enough to realize how little we know, how little we know about the accuracy and completeness of what we think we know, and how much we have to trust God to guide, correct, and increase what we know according to God’s good purposes.

Do we know enough to get to work and make shalom? Yes, we do.

Do we know enough to bear witness to the gospel and make disciples? Yes, we do.

Do we need to claim certainty in order to fulfill the mission of God in these days? No, we don’t.

Certainty isn’t on offer. But confidence—con fide (with faith)—is.

That should be enough for the Christian to get through today with joy and effectiveness. And that’s all that matters (Matt. 6:34).

John G. Stackhouse Jr. is the Sangwoo Youtong Chee Professor of Theology and Culture at Regent College, Vancouver, Canada. He is the author of Need to Know: Vocation as the Heart of Christian Epistemology.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Radical faith answers radical doubt appeared first on OUPblog.

By: AlyssaB,

on 7/17/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

christianity,

reid,

Need to Know,

epistemology,

John G. Stackhouse Jr.,

john stackhouse,

Vocation as the Heart of Christian Epistemology,

stackhouse,

peak skepticism,

thomas reid,

hume—reid,

Religion,

Philosophy,

Humanities,

*Featured,

Christian Epistemology,

Books,

Add a tag

This is the third in a four-part series on Christian epistemology titled “Radical faith meets radical doubt: a Christian epistemology for skeptics” by John G. Stackhouse, Jr.

By John G. Stackhouse, Jr.

We are near, it seems, “peak skepticism.” We all know that the sweetest character in the movie we’re watching will turn out to be the serial killer. We all know that the stranger in the good suit and the great hair is up to something sinister. We all know that the honey-voiced therapist or the soothing guru or the brave leader of the heroic little NGO will turn out to be a fraud, embezzling here or seducing there.

“I read it on the Internet” became a rueful joke as quickly as there was an Internet. Politicians are all liars, priests are all pedophiles, professors are all blowhards: you can’t trust anyone or anything.

Notre Dame philosopher Alvin Plantinga shrugs off the contemporary storm of frightening doubt, however, with the robust common sense of his Frisian forebears:

Such Christian thinkers as Pascal, Kierkegaard, and Kuyper…recognize that there aren’t any certain foundations of the sort Descartes sought—or, if there are, they are exceedingly slim, and there is no way to transfer their certainty to our important non-foundational beliefs about material objects, the past, other persons, and the like. This is a stance that requires a certain epistemic hardihood: there is, indeed, such a thing as truth; the stakes are, indeed, very high (it matters greatly whether you believe the truth); but there is no way to be sure that you have the truth; there is no sure and certain method of attaining truth by starting from beliefs about which you can’t be mistaken and moving infallibly to the rest of your beliefs. Furthermore, many others reject what seems to you to be most important. This is life under uncertainty, life under epistemic risk and fallibility. I believe a thousand things, and many of them are things others—others of great acuity and seriousness—do not believe. Indeed, many of the beliefs that mean the most to me are of that sort. I realize I can be seriously, dreadfully, fatally wrong, and wrong about what it is enormously important to be right. That is simply the human condition: my response must be finally, “Here I stand; this is the way the world looks to me.”

In this attitude Plantinga follows in the cheerful train of Thomas Reid, the great Scottish Enlightenment philosopher. In his several epistemological books, Reid devotes a great deal of energy to demolishing what he sees to be a misguided approach to knowledge, which he terms the “Way of Ideas.” Unfortunately for standard-brand modern philosophy, and even for most of the rest of us non-philosophers, the Way of Ideas is not merely some odd little branch but the main trunk of epistemology from Descartes and Locke forward to Kant.

The Way of Ideas, roughly speaking, is the basic scheme of perception by which the things “out there” somehow cause us to have ideas of them in our minds, and thus we form appropriate beliefs about them. Reid contends, startlingly, that this scheme fails to illuminate what is actually happening. In fact, Reid pulverizes this scheme as simply incoherent—an understanding so basic that most of us take it for granted, even if we could not actually explain it. The “problem of the external world” remains intractable. We just don’t know how we reliably get “in here” (in our minds) what is “out there” (in the world).

Having set aside the Way of Ideas, Reid then stuns the reader again with this declaration: “I do not attempt to substitute any other theory in [its] place.” Reid asserts instead that it is a “mystery” how we form beliefs about the world that actually do seem to correspond to the world as it is. (Our beliefs do seem to have the virtue of helping us negotiate that world pretty well.)

The philosopher who has followed Reid to this point now might well be aghast. “What?” she might sputter. “You have destroyed the main scheme of modern Western epistemology only to say that you don’t have anything better to offer in its place? What kind of philosopher are you?”

“A Christian one,” Reid might reply. For Reid takes great comfort in trusting God for creating the world such that human beings seem eminently well equipped to apprehend and live in it. Reid encourages readers therefore to thank God for this provision, this “bounty of heaven,” and to obey God in confidence that God continues to provide the means (including the epistemic means) to do so. Furthermore, Reid affirms, any other position than grateful acceptance of the fact that we believe the way we do just because that is the way we are is not just intellectually untenable, but (almost biblically) foolish.

Thus Thomas Reid dispenses with modern hubris on the one side and postmodern despair on the other. To those who would say, “I am certain I now sit upon this chair,” Reid would reply, “Good luck proving that.” To those who would say, “You just think you’re sitting in a chair now, but in fact you could be anyone, anywhere, just imagining you are you sitting in a chair,” he would simply snort and perhaps chastise them for their ingratitude for the knowledge they have gained so effortlessly by the grace of God.

Having acknowledged the foolishness of claiming certainty, Reid places the burden of proof, then, where it belongs: on the radical skeptic who has to show why we should doubt what seems so immediately evident, rather than on the believer who has to show why one ought to believe what seems effortless to believe. Darkness, Reid writes, is heavy upon all epistemological investigations. We know through our own action that we are efficient causes of things; we know God is, too. More than this, however, we cannot say, since we cannot peer into the essences of things. Reid commends to us all sorts of inquiries, including scientific ones, but we will always be stymied at some level by the four-year-old’s incessant question: “Yes, but why?” Such explanations always come back to questions of efficient causation, and human reason simply cannot lay bare the way things are in themselves so as to see how things do cause each other to be this or that way.

Reid’s contemporary and countryman David Hume therefore was right on this score, Reid allows. But unlike Hume—very much unlike Hume—Reid is cheerful about us carrying on anyway with the practically reliable beliefs we generally do form, as God wants us to do. Far from being paralyzed by epistemological doubt, therefore, Reid offers all of us a thankful epistemology of trust and obedience.

But do Christians need to resort to such a breathtakingly bold response to the deep skepticism of our times? My last post offers an answer.

John G. Stackhouse Jr. is the Sangwoo Youtong Chee Professor of Theology and Culture at Regent College, Vancouver, Canada. He is the author of Need to Know: Vocation as the Heart of Christian Epistemology.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Approaching peak skepticism appeared first on OUPblog.

By: AlyssaB,

on 7/16/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Religion,

authority,

Memory,

christianity,

Humanities,

Need to Know,

*Featured,

epistemology,

certainty,

Christian Epistemology,

John G. Stackhouse Jr.,

john stackhouse,

Vocation as the Heart of Christian Epistemology,

exaggeration,

expert knowledge,

ioannidis,

stackhouse,

Books,

Add a tag

This is the second in a four-part series on Christian epistemology titled “Radical faith meets radical doubt: a Christian epistemology for skeptics” by John G. Stackhouse, Jr.

By John G. Stackhouse, Jr.

We might have reason to doubt some or even much of our day-to-day apprehension of things. We’re all in a hurry, all having to learn and discern and decide on the fly. Surely in the realm of medical research, however, the most important research we conduct, expert knowledge is sure and sound? David H. Freedman, in his disturbing book Wrong, introduces us to Dr. John Ioannidis. You’ll never sleep well again.

Ioannidis, an expert in expert medical studies, has impressive credentials. Graduating first in his class from the University of Athens Medical School, he completed a residency at Harvard in internal medicine and then took up a research and clinical appointment at Tufts in infectious diseases. While at Tufts, however, he began to notice that a wide range of medical treatment did not rest on solid scientific evidence. While next at the National Institutes of Health and Johns Hopkins University in the 1990s, Ioannidis stated that two-thirds of hundreds of medical studies he read in the scholarly literature were either fully refuted or pronounced “exaggerated” within a few years of their publication.

Ioannidis, an expert in expert medical studies, has impressive credentials. Graduating first in his class from the University of Athens Medical School, he completed a residency at Harvard in internal medicine and then took up a research and clinical appointment at Tufts in infectious diseases. While at Tufts, however, he began to notice that a wide range of medical treatment did not rest on solid scientific evidence. While next at the National Institutes of Health and Johns Hopkins University in the 1990s, Ioannidis stated that two-thirds of hundreds of medical studies he read in the scholarly literature were either fully refuted or pronounced “exaggerated” within a few years of their publication.

This seems troubling. Be more troubled, however, as Freedman continues:

[Ioannidis] had been examining only the less than one-tenth of one percent of published medical research that makes it [in]to the most prestigious medical journals.… Ioannidis did find one group of studies that more often than not remained unrefuted: randomized controlled studies… that appeared in top journals and that were cited in other researchers’ papers an extraordinary one thousand times or more. Such studies are extremely rare and represent the absolute tip of the tip of the pyramid of medical research. Yet one-fourth of even these studies were later refuted, and that rate might have been much higher were it not for the fact that no one had ever tried to confirm or refute nearly half of the rest.

To confirm your permanent insomnia, journalist Julian Sher examines the world of forensic science and finds many instances of wrongful convictions. He points to a 2009 study published in the Virginia Law Review that surveyed the cases of 137 convicted persons later exonerated by DNA evidence, and found that in more than half of the trials forensic experts gave invalid testimony, “including errors about shoe prints and hair samples.” That same year, the National Academy of Sciences published a book-length report warning that even fingerprint matches can be misleading and calling for a drastically improved approach to forensic science. So much, then, for people’s fates being determined by the clear, cold, infallible judgment of the scientific expert witness. (So much, also, for the entire CSI franchise…)

As the world begins to shimmer ever more before our eyes and the solid ground beneath our feet threatens to evanesce, along comes historian Alison Winter to offer an entire book about the questionable reliability of Memory. What we do not readily comprehend, what does not fit within our set of presuppositions, does not tend to register with us immediately and clearly, if at all, and therefore also not in our memory. Conversely, what we expect to experience, or afterward believe we must have experienced, gets written into our memories despite what may have actually happened.

Contrary, that is, to the popular notion that somewhere buried in our brains is a perfect recording of everything we have ever experienced, Winter shows through her study of the last century of memory research that our minds instead are constantly coding what we experience as “memorable,” “sort of memorable,” “not memorable” and the like, according to our understanding of the world and according to our valuing of this or that element of the world.

Furthermore, our memories are plastic, and remain vulnerable to addition, subtraction, deformation, reformation, confabulation, and other processes as our lives progress and as our beliefs change, rather than being fixed, veracious “imprints” of the external world upon our minds.

What, then, can we possibly trust in our quest for knowledge? If we cannot trust our own senses, reason, memory—or even those of the most expert experts in our society—are we simply lost in the blooming, buzzing confusion of an incomprehensible world?

In a word, yes. Yes, we are.

John G. Stackhouse Jr. is the Sangwoo Youtong Chee Professor of Theology and Culture at Regent College, Vancouver, Canada. He is the author of Need to Know: Vocation as the Heart of Christian Epistemology.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Laboratory technicians at work in medical plant with machinery and computers. © diego_cervo via iStockphoto.

The post Certainty and authority appeared first on OUPblog.

By: AlyssaB,

on 7/15/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Religion,

christianity,

Humanities,

Need to Know,

*Featured,

epistemology,

Christian Epistemology,

John G. Stackhouse Jr.,

john stackhouse,

Vocation as the Heart of Christian Epistemology,

Add a tag

This is the first in a four-part series on Christian epistemology titled “Radical faith meets radical doubt: a Christian epistemology for skeptics” by John G. Stackhouse, Jr.

By John G. Stackhouse, Jr.

Right now I’m bored. I can’t be wrong about that. I truly am yawningly, dazedly bored. Epistemologists assure me that about my mental states, such as this present one of stupefaction, I can claim certainty. More sharply, if I am feeling pain, then I am certainly feeling pain. It might be triggered by an injury, or the phenomenon of “phantom pain” after an amputation, or the probe of a neurosurgeon in my brain, but whatever the cause, “I am feeling pain” is a statement I can make with absolute certainty.

Alas, there are precious few such statements one can make. In this so-called Information Age, in which we have more access to more data than ever before, we also live in the age of Photoshop, scams, phishing, and the lot; in a post-Sixties cloud of unknowing in which we doubt the claims of any purported authority. Surrounded by a world of knowledge, we feel less and less able to trust any of it.

Radical doubt is hardly a new problem, of course. The ancient Chinese sage Zhuang-zi wondered if he was a man dreaming he was a butterfly, or possibly instead a butterfly dreaming he was a man. The Wachowski brothers (as they were at the time) brought us The Matrix, merely the most popular of cinematic head trips making us doubt the reality of our quotidian percepts—from Total Recall to Inception to, well, the remake of Total Recall.

Still from The Matrix, courtesy of Warner Bros. Entertainment.

In between, however, we had the robust confidence of the early Enlightenment and the Scientific Revolution. Here, at least, was a time when philosophers and scientists had the world by the tail and could confidently pronounce upon it.

Take John Locke, for example. Here, at least, we have someone who knows what he knows and sets the empiricist tradition of the Enlightenment firmly on its way to greater and greater knowledge of the world.

Except Locke, despite the textbooks, didn’t think that way about thinking. After two centuries of religious and political upheaval in Britain, in the late 1600s John Locke thought it was time to settle everyone down. The great political philosopher was also an epistemologist and epistemology came readily to the aid of his politics.

Instead of prosecuting politics with a fanatical certainty that could tolerate no alternatives, he advised his reader: bethink yourself as to just how certain you can claim to be. You will find that you are not nearly so entitled to certainty as you thought you were. In fact, legitimate certainty is rare and restricted to only one zone: one’s own mental states. You cannot be less than certain, since you cannot possibly be wrong, about what you are experiencing, whether joy or pain. (Sound familiar?) The common epistemic situation instead is to be more or less convinced by more or less convincing evidences and inferences.

The common practice to that point, to be sure, was to simply believe or not believe. Locke’s predecessors and contemporaries, he contended, had foolishly taken onboard all sorts of dubious and even pernicious ideas without submitting them to the scrutiny of critical reason. Worse, they then had elevated various versions of this mish-mash to the level of dogma, and proceeded to fight religious wars over them. In short, people had not governed their beliefs properly heretofore.

The proper attitude instead, Locke averred, is to proportion one’s assent in any given case to the strength of the evidences as adjudicated by Reason. One thus is in an epistemological position to grant that other people’s views may have at least some grounding. One might even learn something from particularly impressive alternatives. An attitude of tolerance for alternatives is thus in order, fanaticism should disappear, and political, ideological, and even religious pluralism can flourish.

Across the Channel, scientist and theologian Blaise Pascal likewise anticipated our postmodern doubts as he warned:

Man is nothing but a subject full of natural error that cannot be eradicated except through grace. Nothing shows him the truth, everything deceives him. The two principles of truth, reason and senses, are not only both not genuine, but are engaged in mutual deception. The senses deceive reason through false appearances, and, just as they trick the soul, they are tricked by it in their turn: it takes its revenge. The senses are disturbed by passions, which produce false impressions. They both compete in lies and deception.

Surely, though, we have come a long way since the seventeenth century? Surely we can have much firmer footing for our beliefs today, The Matrix notwithstanding?

One main reason for our lack of certainty is that our brains still process the world the way our ancestors did. It’s not a bad way to process the world. Quite the contrary, in fact: it is generally efficient and reliable. But it is a long way from providing us certainty about much of anything.

Nobel Prize-winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman sums up much of his career in his popular book Thinking, Fast and Slow. He suggests that we typically respond to the world in something very like a reflexive mode: apprehending, comprehending, and responding to what we encounter with as little intellectual effort as possible. We therefore “process” the world along well-worn intellectual pathways, habits of apprehension, comprehension, and response (Kahneman uses the term “heuristics”) that have served us well in the past and require little effort to traverse again.

Our natural resort to such habits, of course, helps us avoid traffic dangers smoothly, return a tennis serve accurately, and greet a stranger at a party politely. But our reliance on what Kahneman calls System 1 thinking means that we often miss opportunities to apprehend, comprehend, or respond to reality as well as we might—or ought. For on the dark side of System 1 thinking is convention, bias, even prejudice, the very opposites of insightful, creative, and independent thinking.

Indeed, System 1 thinking is “a machine for jumping to conclusions,” Kahneman says. It is an awfully useful machine—indeed, we could not survive, let alone thrive, without it. But its very speed, general reliability, and relative ease-of-use means that we tend always to resort to it unless we feel we simply have to slow down and think about things in a concentrated way. Then we employ System 2, the mode of complex calculations, critical re-examination of information, and the posing of creative alternatives. Even then, however, we use System 2 only as much and for as long as we feel we need to do so. We are, Kahneman concludes, basically lazy thinkers.

Stanford business professor Chip Heath and his Aspen Institute-consultant brother Dan confirm from abundant research that the ideas that make the most immediate and lasting impact on people generally have qualities that have nothing to do with their veracity: simplicity, unexpectedness, concreteness, a measure of credibility, emotional impact, and a vivid exemplifying narrative (Made to Stick). Thus contrary ideas that are more complex, banal, abstract, equally credible, dull, and bereft of a fascinating story cannot compete—even if they have the single quality that matters: truth.

One might assume that those we trust as authorities can rise above the habits of the mass. Journalist David H. Freedman will keep you awake at night, however, by his account (with the wonderful title, Wrong) of just how frequently experts have been wrong nonetheless.

That upsetting news is in my next post.

John G. Stackhouse Jr. is the Sangwoo Youtong Chee Professor of Theology and Culture at Regent College, Vancouver, Canada. He is the author of Need to Know: Vocation as the Heart of Christian Epistemology.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The butterfly and the matrix appeared first on OUPblog.

Ioannidis, an expert in expert medical studies, has impressive credentials. Graduating first in his class from the University of Athens Medical School, he completed a residency at Harvard in internal medicine and then took up a research and clinical appointment at Tufts in infectious diseases. While at Tufts, however, he began to notice that a wide range of medical treatment did not rest on solid scientific evidence. While next at the National Institutes of Health and Johns Hopkins University in the 1990s, Ioannidis stated that two-thirds of hundreds of medical studies he read in the scholarly literature were either fully refuted or pronounced “exaggerated” within a few years of their publication.

Ioannidis, an expert in expert medical studies, has impressive credentials. Graduating first in his class from the University of Athens Medical School, he completed a residency at Harvard in internal medicine and then took up a research and clinical appointment at Tufts in infectious diseases. While at Tufts, however, he began to notice that a wide range of medical treatment did not rest on solid scientific evidence. While next at the National Institutes of Health and Johns Hopkins University in the 1990s, Ioannidis stated that two-thirds of hundreds of medical studies he read in the scholarly literature were either fully refuted or pronounced “exaggerated” within a few years of their publication.