By Anatoly Liberman

Last week I wrote about Henry Bradley’s role in making the OED what it is: a mine of information, an incomparable authority on the English language, and a source of inspiration to lexicographers all over the world. New words appear by the hundred, new methods of research develop, and many attitudes have changed in the realm of etymology since the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth century, but nothing said in the great dictionary has become useless, even though numerous conjectures and formulations have to be revised.

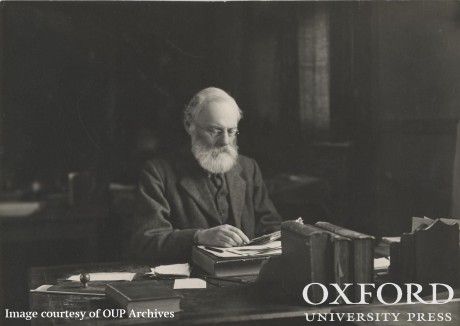

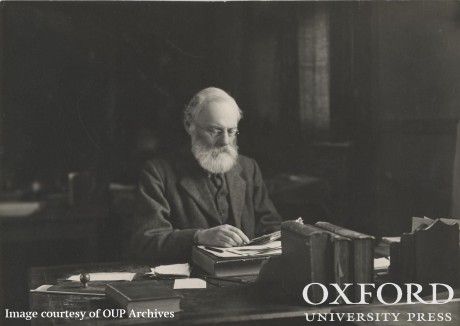

Unfortunately, the world knows little about those who did all the work. It will probably not be an exaggeration to say that before Katharine Maud Elisabeth Murray wrote a book on her grandfather (1977) and gave it the wonderful title Caught in the Web of Words, few people outside the profession had any notion of who James A. H. Murray, the OED’s senior editor, was. Samuel Johnson’s definition of a lexicographer as a harmless drudge has been trodden to death by authors who live on borrowed wit. Alas, very often the only way to honor a distinguished “drudge” is to publish a short obituary, usually forgotten on the same day. As I mentioned last time, Bradley had better luck: a posthumous volume of his collected works appeared in 1928. I was happy to see his archival picture in my post. Many eminent scholars of that epoch were photographed in the same position, so that they look like venerable old twins, writing desk, glasses, beard and all. Yet this picture is different from the one reproduced in the 1928 book.

How harmless lexicographers are I cannot tell. It seems that, with regard to character, this profession, like any other, is, to use the most popular word of our time, diverse. In any case, lexicographers do not only shuffle index cards and sit at computers, trying to disentangle themselves from the web of words: they have opinions about many things, not related directly to the art of dictionary making. For example, both Bradley and Skeat had non-trivial ideas about spelling reform. Today I will summarize Bradley’s views. Skeat’s turn will come round next Wednesday. To begin with, Bradley, who made his thoughts public in 1913, was an opponent of Simplified Spelling, but he addressed only one side of the reform, namely the proposal that phonetic spelling should be adopted. In making his position clear, he advanced several perfectly valid arguments but overlooked perhaps the most important aspect of the problem.

In one respect, Bradley was decades ahead of his time. He insisted that the written form of Modern English and of any language using letters, far from being a mechanical transcript of oral speech, has a life of its own. This is perfectly true. Much later, the members of the Prague Linguistic Circle, a great school of European structuralism, made the same point. Bradley wrote: “Among peoples in which many persons write and read much more than they speak and hear, the written language tends to develop more or less independently of the spoken language.” He referred with admiration to the epoch of ideographic writing, when characters were pictures. Even today, he stated, we never read letter by letter, but grasp whole words. So we do, and for this reason we tend to overlook typos. Bradley did not object to many English words being ideograms, or images that have to be memorized and remain independent of the sounds of which they consist. Many scholarly words are familiar to us only from books; they are hardly ever pronounced, so may they preserve their familiar form, he said.

Bradley made his attitude clear: English spelling is an heir to an age-long tradition and should be reformed with care. Sounds, he added, change, and, “when change of pronunciation had made a spoken word ambiguous, the retention of the old unequivocal written form is a great practical convenience. It makes the written language, so far, a better instrument of expression than the spoken language.” Sometimes he was forcing open doors, but in his days there was no theory of orthography, and his point is well taken. Indeed, modern spelling has several (though hardly equally important) functions. For example, it may connect related words, in violation of the phonetic principle. Thus, k- in know ~ knowledge is a nuisance (I was almost tempted to write knuisance), but it should probably be retained by reformers because k- is pronounced in acknowledge (however, I am afraid that aknowledge would be quite enough).

It may be convenient that in some situations we bow to the ideographic principle and have write, wright ~ Wright, and rite. The recent invention of phishing is characteristic: it designates fishing for customers in muddy waters, fishing with an evil flourish (phlourish?). Bradley did not cite rite and its kin, but referred to hole and whole, son and sun, night and knight among numerous other homophones, which are not homographs. (Homophones sound alike; homographs are spelled alike.) He quoted the line Nor burnt the grange, no buss’d the milking-maid (buss means “kiss”) and remarked that Tennyson would not have agreed to write bust for bus’t; hence the virtue of the apostrophe. When words are spelled differently, we are apt to ascribe different meanings to them. This is again correct. Bradley recalled the case of grey versus gray (see my post on this word): many people, especially artists, when asked about their thoughts on those adjectives, replied that they associate gray and grey with different colors.

Bradley agreed that the spelling of some words should be changed. He admitted that it may be useful to teach children some variant of phonetic spelling before introducing them to letters, for this would make them aware of the sounds they pronounce. But phonetic spelling as the aim of a sweeping reform was unacceptable to him. I am all for simplifying English spelling, but I think Bradley was right—not so much for theoretical as for practical reasons. The English speaking world will never agree to a revolution, and promoting a hopeless cause is a waste of time. But the most interesting aspect of Bradley’s attack on the reform is his general attitude. He addressed only the needs of those who had already mastered the intricacies of English spelling. Obviously, to someone who learned that choir is quire and a playwright is not a playwrite, even though this person writes plays, any change will be an irritation. But the advocates of the reform have the uneducated in mind. They and Bradley speak at cross-purposes.

Strangely, only one aspect of English spelling worried Bradley: the existence of many words like bow as in make a low bow and bow in bow and arrow. This situation, he thought, had to be changed, even though he could not offer any advice. In his opinion, words that sounded differently had to be spelled differently. “The task of rectifying these anomalies, and of making the many readjustments with their correction will render necessary, will require great ingenuity and thought.” Consequently, homophones may be spelled differently (right, write, wright, Wright, rite), but homographs should be homophones (for this reason, bow1 and bow2, read and its past read, etc. need different visual representations).

The rest of Bradley’s argumentation against the reformers is traditional (English speakers pronounce words differently: for example, lord and laud are not homophones with 90% of English speakers, and so forth) and need not be discussed here, but we will return to it in connection with Skeat’s passionate defense of the reform.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Theodore Roosevelt cartoon via Almanac of Theodore Roosevelt.

The post Henry Bradley on spelling reform appeared first on OUPblog.

By Anatoly Liberman

At one time I intended to write a series of posts about the scholars who made significant contributions to English etymology but whose names are little known to the general public. Not that any etymologists can vie with politicians, actors, or athletes when it comes to funding and fame, but some of them wrote books and dictionaries and for a while stayed in the public eye. Ernest Weekley authored not only an etymological dictionary (a full and a concise version) but also multiple books on English words that were read and praised widely in the twenties and thirties of the twentieth century. Walter Skeat dominated the etymological scene for decades, and his “Concise Dictionary” graced many a desk on both sides of the Atlantic. James Murray attained glory as the editor of the Oxford English Dictionary. (Curiously, for a long time people, at least in England, used to say that words should be looked up “in Murray,” as we now say “in Skeat” or “in Webster.” Not a trace of this usage is left. “Murray” yielded to the anonymous NED [New English Dictionary] and then to OED, with or without the definite article).

Those tireless researchers deserved the recognition they had. But there also were people who formed a circle of correspondents united by their devotion to some journal: Athenaeum, The Academy, and their likes. Most typically, the same subscribers used to send letters to Notes and Queries year in, year out. As a rule, they are only names to me and probably to most of our contemporaries, but the members of that “club” often knew one another or at least knew who the writers were, and being visible in Notes and Queries amounted to a thin slice of international fame. Having run (for the sake of my bibliography of English etymology) through the entire set of that periodical twice, I learned to appreciate the correspondents’ dedication to scholarship and their erudition. I learned a good deal about their way of life, their libraries, and their antiquarian interests, but not enough to write an entertaining essay devoted to any one of them. That is why my series died after the first effort, a post on Dr. Frank Chance (Dr. means “medical doctor” here), and I still hope that one day Oxford University Press will publish a collection of his excellent short articles on English and French subjects.

To be sure, Henry Bradley is not an obscure figure, but even in his lifetime he was never in the limelight. And yet for many years he was second in command at the OED and, when Murray died, replaced him as NO. 1. In principle, the OED, conceived as a historical dictionary, did not have to provide etymologies. But the Philological Society always wanted origins to be part of the entries. Hensleigh Wedgwood was at one time considered as a prospective Etymologist-in-Chief, but it soon became clear that he would not do: his blind commitment to onomatopoeia and indifference to the latest achievements of historical linguistics disqualified him almost by definition despite his diligence and ingenuity. Skeat may not have aspired for that role. In any case, James Murray decided to do the work himself. That he turned out to be such an astute etymologist was a piece of luck.

Beginning with 1884, Bradley became an active participant in the dictionary. According to Bridges, in January 1888 he sent in the first instalment of his independent editing (531 slips). In the same year he was acknowledged as Joint Editor, responsible for his own sections, in 1896 he moved to Oxford, and from 1915, after the death of Murray in July of that year, he served as Senior Editor. In 1928 Clarendon Press published The Collected Papers of Henry Bradley, With a Memoir by Robert Bridges, and it is from this memoir that I have all the dates. About the move to Oxford, Bridges wrote: “He definitely entered into bondage and sold himself to slave henceforth for the Dictionary.” (How many people still remember the poetry of Robert Bridges?)

James Murray was a jealous man. He might have preferred to go on without a senior assistant, but even he was unable to do all the editing alone. It could not be predicted that Bradley would trace the history of words, inherited and borrowed, so extremely well. Once again luck was on the side of the great dictionary. In 1923, when Bradley died, not much was left to do. Even today, despite a mass of new information, the appearance of indispensable dictionaries and databases (to say nothing of the wonders of technology), as well as the publication of countless works on archeology, every branch of Indo-European, and the structure of the protolanguage and proto-society, the original etymologies in the OED more often than not need revision rather than refutation. This fact testifies to Murray’s and Bradley’s talent and to the reliability of the method they used.

Bradley joined the ictionary after Murray read his review of the first installments of the OED (The Academy, February 16, pp. 105-106, and March 1, pp. 141-142; I am grateful to the OED’s Peter Gilliver for checking and correcting the chronology). Bridges wrote about that review: “…its immediate publication revealed to Dr. Murray a critic who could give him points.” But today, 140 years later, one wonders what impressed Murray so much in Bradley’s remarks and what points “the critic” could give him. Bradley did not conceal his admiration for what he had seen, suggested a few corrections, and expressed the hope that “the work [would] be carried to its conclusion in a manner worthy of this brilliant commencement.” It can be doubted that Murray melted at the sight of the compliments: with two exceptions, everybody praised the first fascicles, and those who did not wrote mean-spirited reports. More probably, he sensed in Bradley someone who had a thorough understanding of his ideas and a knowledgeable potential ally (Bradley’s pre-1883 articles were neither numerous nor earth shattering). If such was the case, he guessed well.

Finding word origins was only one small (even if the trickiest) part of the editors’ duties, but my subject is limited to this single aspect of their activities. The title of Bradley’s posthumous volume, The Collected Papers, should not be mistaken for The Complete Works. Nor was such a full collection needed, though some omissions cause regret. Like Murray, Bradley wrote many short notes (especially often to The Academy, of which long before his move to Oxford he was editor for a year). My database contains sixty-five titles under his name. Here are some of them: “Two Mistakes in Littré’s French Dictionary,” “Obscure Words in Middle English,” “The Etymology of the Word god,” “Dialect and Etymology” (the latter in the Transactions of the Yorkshire Dialect Society; Bradley was born in Manchester, so not in Yorkshire), numerous reviews and equally numerous reports, some of whose titles evoke today unexpected associations, as, for example, “F-words in NED” (the secretive year of 1896, when the F-word could not be included!).

Bradley had edited and revised the only full Middle English dictionary then in use. The modest reference to “obscure words” gives no idea of how well he knew that language. And among The Collected Papers the reader will find, among others, his contributions on Beowulf and “slang” to the Encyclopaedia Britannica, ten essays on place names (one of his favorite subjects), and a whole section of literary studies. Those deal with Old and Middle English, and in several cases his opinion became definitive. Bradley’s tone was usually firm (he made no bones about disagreeing with his colleagues) but courteous. Although he sometimes chose to pity an indefensible opinion, the vituperative spirit of nineteenth-century British journalism did not rub off on him. Nor was he loath to admit that his conclusions might be wrong. Temperamentally, he must have been the very opposite of Murray.

One of Bradley’s papers is of special interest to us, and it was perhaps the most influential one he ever wrote. It deals with the chances of reforming English spelling. I will devote a post to it next week.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Image courtesy of OUP Archives.

The post Unsung heroes of English etymology: Henry Bradley (1845-1923) appeared first on OUPblog.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears on the OUPblog each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.” Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology articles via email or RSS.