What are the optimal conditions for commercializing technology breakthroughs? How can we develop a common framework among universities, government, and businesses for generating fundamentally fresh insights? How can the government maximize the public’s return on research and development investments? Innovation is a important topic in both the public and the private sectors, yet no one can agree the best path forward for it. We present a brief excerpt from Organized Innovation: A Blueprint for Renewing America’s Prosperity by Steven C. Currall, Ed Frauenheim, Sara Jansen Perry, and Emily M. Hunter.

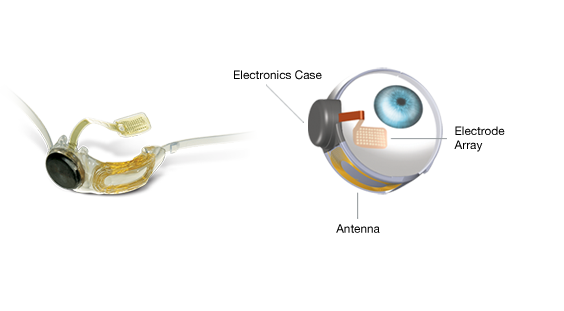

Professor Mark Humayun and his colleagues have created a small device with a big story to tell. It is an artificial retina, whose electronics sit in a canister smaller than a dime, and that literally allows the blind to see. The device also reflects a new approach to innovation that can help America find its way to a more hopeful, prosperous future.

During the late 1980s, Humayun was in medical school preparing to be a neurosurgeon. But his grandmother’s loss of vision put him on a quest to create technology that would help people see again. He switched his focus to ophthalmology, earned his MD, and imagined an implant to send digital images to the optic nerve. But when he asked biomedical engineers to help him develop such a device, he found they spoke a different language.

“I remember trying to tell them I wanted to pass a current to stimulate the retina. I wanted to excite neurons in a blind person’s eyes. They looked at me and said, ‘What?’” he recalls. “I couldn’t communicate what I wanted.” So Humayun did something that remains rare among American researchers: he crossed over into a different discipline. He earned a doctorate in biomedical engineering at the University of North Carolina.

By 1992 Humayun and his team of fellow researchers, then at Johns Hopkins University, had a rudimentary prototype of an artificial retina. But they still had a long ways to go. In 2001, Humayun and his key collaborators moved to the University of Southern California to continue their work on the retinal prosthesis. Humayun also helped form a start-up company, Second Sight, which aimed to commercialize the implant. And in 2003 Humayun and his colleagues won a National Science Foundation (NSF) grant to launch a research center to pursue retinal prostheses and other potential medical implants.

The Argus II artificial retina can restore a form of sight to patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Image courtesy of Second Sight Medical Products.

That center—the Biomimetic MicroElectronic Systems program—is part of a broader National Science Foundation initiative called the Engineering Research Center (ERC) program. The ERC program embodies government research funding as well as principles of planning, teamwork, and smart management. And it has quietly achieved remarkable success, returning to the US economy more than tenfold the $1 billion invested in it between 1985 and 2009.

The USC-based ERC prompted researchers to put their basic research projects on a path toward commercial prototypes. It also cultivated connections between academics and private- sector executives, as well as between researchers of different disciplines. And it provided funding for ten years—much longer than the typical academic grant.

During Humayun’s leadership of the ERC, his team hit several milestones. Most visibly, the artificial retina won approval from regulators in Europe and the Food and Drug Administration in the United States, and began changing people’s lives. The BBC broadcast a segment of a once-blind grandmother playing basketball—and making shots—with her grandson. The video went viral.

As Humayun and his team expand into other applications of artificial implants, the possibilities resemble science fiction—for example, improving short-term memory loss, headaches, and depression. In short, Humayun and his ERC team remind us that America can achieve fundamental technology breakthroughs—the sort that improve lives, launch new industries and create good jobs.

But we must improve our innovation efforts. Global competition has intensified in recent years, as other nations have ramped up their technology commercialization capabilities. At the same time, the U.S. innovation ecosystem has devolved into an unorganized, suboptimal approach. An “innovation gap” has emerged in recent decades, where U.S. universities focus on basic research and industry concentrates on incremental product development. This book aims to give U.S. leaders a blueprint for closing that gap and improving our ability to compete.

Based on the successes of the Biomimetic MicroElectronic Systems center and other ERCs, we have developed a framework we call Organized Innovation. Organized Innovation is a systematic method for leading the translation of scientific discoveries into societal benefits through commercialization. At its core is the idea that we can, to a much greater extent than generally thought possible, organize the conditions for technology breakthroughs that lead to new products, companies, and world-leading industries.

Organized Innovation consists of three pillars, or “three Cs”:

- Channeled Curiosity refers to the marriage of curiosity-driven research and strategic planning.

- Boundary-Breaking Collaboration refers to a radical dismantling of traditional research and academic silos to spur collective creativity and problem solving.

- Orchestrated Commercialization means coaxing the different players, including researchers, entrepreneurs, financial investors, and corporations so that they make innovations real for global use.

If we can recognize the importance of Organized Innovation, we are confident the United States can restore its vision as a technology leader, revitalize its economy and employment levels, and help to resolve pressing global problems. We are confident, in other words, that America can produce many more big breakthroughs like the small device created by Mark Humayun and his colleagues.

Steven C. Currall is Dean and Professor at the Graduate School of Management at University of California, Davis; Ed Frauenheim is Content & Curation Specialist for the Great Place to Work Institute; Sara Jansen Perry is Assistant Professor of Management at the University of Houston-Downtown; and Emily Hunter is Assistant Professor at the Hankamer School of Business at Baylor University. They are the co-authors of Organized Innovation: A Blueprint for Renewing America’s Prosperity, published by Oxford University Press.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only business and economics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Restoring our innovation “vision” appeared first on OUPblog.