new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: 2014 middle grade fiction, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 9 of 9

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: 2014 middle grade fiction in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 7/25/2014

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Best Books of 2014,

Reviews 2014,

2014 reviews,

2014 middle grade fiction,

2015 Newbery contender,

2014 historical fiction,

Reviews,

historical fiction,

Scholastic,

Best Books,

Christopher Paul Curtis,

middle grade historical fiction,

Add a tag

The Madman of Piney Woods

The Madman of Piney Woods

By Christopher Paul Curtis

Scholastic

ISBN: 978-0-545-63376-5

$16.99

Ages 9-12

On shelves September 30th

No author hits it out of the park every time. No matter how talented or clever a writer might be, if their heart isn’t in a project it shows. In the case of Christopher Paul Curtis, when he loves what he’s writing the sheets of paper on which he types practically set on fire. When he doesn’t? It’s like reading mold. There’s life there, but no energy. Now in the case of his Newbery Honor book Elijah of Buxton, Curtis was doing gangbuster work. His blend of history and humor is unparalleled and you need only look to Elijah to see Curtis at his best. With that in mind I approached the companion novel to Elijah titled The Madman of Piney Woods with some trepidation. A good companion book will add to the magic of the original. A poor one, detract. I needn’t have worried. While I wouldn’t quite put Madman on the same level as Elijah, what Curtis does here, with his theme of fear and what it can do to a human soul, is as profound and thought provoking as anything he’s written in the past. There is ample fodder here for young brains. The fact that it’s a hoot to read as well is just the icing on the cake.

Two boys. Two lives. It’s 1901, forty years after the events in Elijah of Buxton and Benji Alston has only one dream: To be the world’s greatest reporter. He even gets an apprenticeship on a real paper, though he finds there’s more to writing stories than he initially thought. Meanwhile Alvin Stockard, nicknamed Red, is determined to be a scientist. That is, when he’s not dodging the blows of his bitter Irish granny, Mother O’Toole. When the two boys meet they have a lot in common, in spite of the fact that Benji’s black and Red’s Irish. They’ve also had separate encounters with the legendary Madman of Piney Woods. Is the man an ex-slave or a convict or part lion? The truth is more complicated than that, and when the Madman is in trouble these two boys come to his aid and learn what it truly means to face fear.

Let’s be plainspoken about what this book really is. Curtis has mastered the art of the Tom Sawyerish novel. Sometimes it feels like books containing mischievous boys have fallen out of favor. Thank goodness for Christopher Paul Curtis then. What we have here is a good old-fashioned 1901 buddy comedy. Two boys getting into and out of scrapes. Wreaking havoc. Revenging themselves on their enemies / siblings (or at least Benji does). It’s downright Mark Twainish (if that’s a term). Much of the charm comes from the fact that Curtis knows from funny. Benji’s a wry-hearted bigheaded, egotistical, lovable imp. He can be canny and completely wrong-headed within the space of just a few sentences. Red, in contrast, is book smart with a more regulation-sized ego but as gullible as they come. Put Red and Benji together and it’s little wonder they’re friends. They compliment one another’s faults. With Elijah of Buxton I felt no need to know more about Elijah and Cooter’s adventures. With Madman I wouldn’t mind following Benji and Red’s exploits for a little bit longer.

One of the characteristics of Curtis’s writing that sets him apart from the historical fiction pack is his humor. Making the past funny is a trick. Pranks help. An egotistical character getting their comeuppance helps too. In fact, at one point Curtis perfectly defines the miracle of funny writing. Benji is pondering words and wordplay and the magic of certain letter combinations. Says he, “How is it possible that one person can use only words to make another person laugh?” How indeed. The remarkable thing isn’t that Curtis is funny, though. Rather, it’s the fact that he knows how to balance tone so well. The book will garner honest belly laughs on one page, then manage to wrench real emotion out of you the next. The best funny authors are adept at this switch. The worst leave you feeling queasy. And Curtis never, not ever, gives a reader a queasy feeling.

Normally I have a problem with books where characters act out-of-step with the times without any outside influence. For example, I once read a Civil War middle grade novel that shall remain nameless where a girl, without anyone in her life offering her any guidance, independently came up with the idea that “corsets restrict the mind”. Ugh. Anachronisms make me itch. With that in mind, I watched Red very carefully in this book. Here you have a boy effectively raised by a racist grandmother who is almost wholly without so much as a racist thought in his little ginger noggin. How do we account for this? Thankfully, Red’s father gives us an “out”, as it were. A good man who struggles with the amount of influence his mother-in-law may or may not have over her redheaded grandchild, Mr. Stockard is the just force in his son’s life that guides his good nature.

The preferred writing style of Christopher Paul Curtis that can be found in most of his novels is also found here. It initially appears deceptively simple. There will be a series of seemingly unrelated stories with familiar characters. Little interstitial moments will resonate with larger themes, but the book won’t feel like it’s going anywhere. Then, in the third act, BLAMMO! Curtis will hit you with everything he’s got. Murder, desperation, the works. He’s done it so often you can set your watch by it, but it still works, man. Now to be fair, when Curtis wrote Elijah of Buxton he sort of peaked. It’s hard to compete with the desperation that filled Elijah’s encounter with an enslaved family near the end. In Madman Curtis doesn’t even attempt to top it. In fact, he comes to his book’s climax from another angle entirely. There is some desperation (and not a little blood) but even so this is a more thoughtful third act. If Elijah asked the reader to feel, Madman asks the reader to think. Nothing wrong with that. It just doesn’t sock you in the gut quite as hard.

For me, it all comes down to the quotable sentences. And fortunately, in this book the writing is just chock full of wonderful lines. Things like, “An object in motion tends to stay in motion, and the same can be said of many an argument.” Or later, when talking about Red’s nickname, “It would be hard for even as good a debater as Spencer or the Holmely boy to disprove that a cardinal and a beet hadn’t been married and given birth to this boy. Then baptized him in a tub of red ink.” And I may have to conjure up this line in terms of discipline and kids: “You can lead a horse to water but you can’t make it drink, but you can sure make him stand there looking at the water for a long time.” Finally, on funerals: “Maybe it’s just me, but I always found it a little hard to celebrate when one of the folks in the room is dead.”

He also creates little moments that stay with you. Kissing a reflection only to have your lips stick to it. A girl’s teeth so rotted that her father has to turn his head when she kisses him to avoid the stench (kisses are treacherous things in Curtis novels). In this book I’ll probably long remember the boy who purposefully gets into fights to give himself a reason for the injuries wrought by his drunken father. And there’s even a moment near the end when the Madman’s identity is clarified that is a great example of Curtis playing with his audience. Before he gives anything away he makes it clear that the Madman could be one of two beloved characters from Elijah of Buxton. It’s agony waiting for him to clarify who exactly is who.

Character is king in the world of Mr. Curtis. A writer who manages to construct fully three-dimensional people out of mere words is one to watch. In this book, Curtis has the difficult task of making complete and whole a character through the eyes of two different-year-old boys. And when you consider that they’re working from the starting point of thinking that the guy’s insane, it’s going to be a tough slog to convince the reader otherwise. That said, once you get into the head of the “Madman” you get a profound sense not of his insanity but of his gentleness. His very existence reminded me of similar loners in literature like Boys of Blur by N.D. Wilson or The House of Dies Drear by Virginia Hamilton, but unlike the men in those books this guy had a heart and a mind and a very distinctive past. And fears. Terrible, awful fears.

It’s that fear that gives Madman its true purpose. Red’s grandmother, Mother O’Toole, shares with the Madman a horrific past. They’re very different horrors (one based in sheer mind-blowing violence and the other in death, betrayal, and disgust) but the effects are the same. Out of these moments both people are suffering a kind of PTSD. This makes them two sides of the same coin. Equally wracked by horrible memories, they chose to handle those memories in different ways. The Madman gives up society but retains his soul. Mother O’Toole, in contrast, retains her sanity but gives up her soul. Yet by the end of the book the supposed Madman has returned to society and reconnected with his friends while the Irishwoman is last seen with her hair down (a classic madwoman trope as old as Shakespeare himself) scrubbing dishes until she bleeds to rid them of any trace of the race she hates so much. They have effectively switched places.

Much of what The Madman of Piney Woods does is ask what fear does to people. The Madman speaks eloquently of all too human monsters and what they can do to a man. Meanwhile Grandmother has suffered as well but it’s made her bitter and angry. When Red asks, “Doesn’t it seem only logical that if a person has been through all of the grief she has, they’d have nothing but compassion for anyone else who’s been through the same?” His father responds that “given enough time, fear is the great killer of the human spirit.” In her case it has taken her spirit and “has so horribly scarred it, condensing and strengthening and dishing out the same hatred that it has experienced.” But for some the opposite is true, hence the Madman. Two humans who have seen the worst of humanity. Two different reactions. And as with Elijah, where Curtis tackled slavery not through a slave but through a slave’s freeborn child, we hear about these things through kids who are “close enough to hear the echoes of the screams in [the adults’] nightmarish memories.” Certainly it rubs off onto the younger characters in different ways. In one chapter Benji wonders why the original settlers of Buxton, all ex-slaves, can’t just relax. Fear has shaped them so distinctly that he figures a town of “nervous old people” has raised him. Adversity can either build or destroy character, Curtis says. This book is the story of precisely that.

Don’t be surprised if, after finishing this book, you find yourself reaching for your copy of Elijah of Buxton so as to remember some of these characters when they were young. Reaching deep, Curtis puts soul into the pages of its companion novel. In my more dreamy-eyed moments I fantasize about Curtis continuing the stories of Buxton every 40 years until he gets to the present day. It could be his equivalent of Louise Erdrich’s Birchbark House chronicles. Imagine if we shot forward another 40 years to 1941 and encountered a grown Benji and Red with their own families and fears. I doubt Curtis is planning on going that route, but whether or not this is the end of Buxton’s tales or just the beginning, The Madman of Piney Woods will leave child readers questioning what true trauma can do to a soul, and what they would do if it happened to them. Heady stuff. Funny stuff. Smart stuff. Good stuff. Better get your hands on this stuff.

On shelves September 30th.

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

First Sentence: “The old soldiers say you never hear the bullet that kills you.”

Like This? Then Try:

Notes on the Cover: As many of us are aware, in the past historical novels starring African-American boys have often consisted of silhouettes or dull brown sepia-toned tomes. Christopher Paul Curtis’s books tend to be the exception to the rule, and this is clearly the most lively of his covers so far. Two boys running in period clothing through the titular “piney woods”? That kind of thing is rare as a peacock these days. It’s still a little brown, but maybe I can sell it on the authors name and the fact that the books look like they’re running to/from trouble. All in all, I like it.

Professional Reviews:

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 7/8/2014

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reviews,

Lisa Graff,

Penguin,

realistic fiction,

Best Books,

Philomel,

middle grade realistic fiction,

Best Books of 2014,

Reviews 2014,

2014 reviews,

2014 middle grade fiction,

2014 realistic fiction,

Add a tag

Absolutely Almost

Absolutely Almost

By Lisa Graff

Philomel (an imprint of Penguin)

$16.99

ISBN: 978-0-399-16405-7

Ages 9-12

On shelves now.

In the stage musical of Matilda, lyricist Tim Minchin begins the show with the following lines about the state of children today: “Specialness is de rigueur. / Above average is average. Go fig-ueur! / Is it some modern miracle of calculus / That such frequent miracles don’t render each one un-miraculous?” This song ran on a bit of a loop through my cranium as I read Lisa Graff latest middle grade novel Absolutely Almost. For parents, how well your child does reflects right back on you. Your child is a genius? Congratulations! You must be a genius for raising a genius. Your child is above average? Kudos to you. Wait, your child is average? Uh-oh. For some parents nothing in the world could be more embarrassing. We all want our kids to do well in school, but where do you distinguish between their happiness and how hard you’re allowed to push them to do their best? Do you take kindness into account when you’re adding up all their other sterling qualities? Maybe the wonder of Absolutely Almost is that it’s willing to give us an almost unheard of hero. Albie is not extraordinary in any possible way and he would like you to be okay with that. The question then is whether or not child readers will let him.

Things aren’t easy for Albie. He’s not what you’d call much of a natural at anything. Reading and writing is tough. Math’s a headache. He’s not the world’s greatest artist and he’s not going to win any awards for his wit. That said, Albie’s a great kid. If you want someone kind and compassionate, he’s your man. When he finds himself with a new babysitter, a girl named Calista who loves art, he’s initially skeptical. She soon wins him over, though, and good thing too since there are a lot of confusing things going on in his life. One day he’s popular and another he’s not. He’s been kicked out of his old school thanks to his grades. Then there’s the fact that his best friend is part of a reality show . . . well, things aren’t easy for Albie. But sometimes, when you’re not the best at anything, you can make it up to people by simply being the best kind of person.

Average people are tough. They don’t naturally lend themselves to great works of literature generally unless they’re a villain or the butt of a joke. Lots of heroes are billed as “average heroes” but how average are they really? Put another way, would they ever miscalculate a tip? Our fantasy books are full to overflowing of average kids finding out that they’re extraordinary (Percy Jackson, Harry Potter, Meg Murry, etc.). Now imagine that the book kept them ordinary. Where do you go from there? Credit where credit is due to Lisa Graff then. The literary challenge of retaining a protagonist’s everyday humdrum status is intimidating. Graff wrestles with the idea and works it to her advantage. For example, the big momentous moment in this book is when it turns out that Albie doesn’t have dyslexia and just isn’t good at reading. I’ve never seen that in a book for kids before, and it was welcome. It made it clear what kind of book we’re dealing with.

As a librarian who has read a LOT of children’s books starring “average” kids, I kept waiting for that moment when Albie discovered he had a ridiculously strong talent for, say, ukulele or poker or something. It never came. It never came and I was left realizing that it was possible that it never would. Kids are told all the time that someday they’ll find that thing that’ll make them unique. Well what if they don’t? What happens then? Absolutely Almost is willing to tell them the truth. There’s a wonderful passage where Calista and Albie are discussing the fact that he may never find something he’s good at. Calista advises, “Find something you’d want to keep doing forever… even if you stink at it. And then, if you’re lucky, with lots of practice, then one day you won’t stink so much.” Albie points out, correctly, that he might still stink at it and what then? Says Calista, “Then won’t you be glad you found something you love?”

Mind you, average heroes run a big risk. Absolutely Almost places the reader in a difficult position. More than one kid is going to find themselves angry with Albie for being dense. But the whole point of the book is that he’s just not the sharpest pencil in the box. Does that make the reader sympathetic then to his plight or a bully by proxy? It’s the age-old problem of handing the reader the same information as the hero but allowing them to understand more than that hero. If you’re smarter than the person you’re reading about, does that make you angry or understanding? I suppose it depends on the reader and the extent to which they can relate to Albie’s problem. Still, I would love to sit in on a kid book discussion group as they talked about Albie. Seems to me there will be a couple children who find their frustration with his averageness infuriating. The phrase “Choose Kind” has been used to encourage kids not to bully kids that look different than you. I’d be interested in a campaign that gave as much credence to encouraging kids not to bully those other children that aren’t as smart as they are.

I’ve followed the literary career of Lisa Graff for years and have always enjoyed her books. But with Absolutely Almost I really feel like she’s done her best work. The book does an excellent job of showing without telling. For example, Albie discusses at one point how good he is at noticing things then relates a teacher’s comment that, “if you had any skill at language, you might’ve made a very fine writer.” Graff then simply has Albie follow up that statement with a simple “That’s what she said.” You’re left wondering if he picked up on the inherent insult (or was it just a truth?) in that. Almost in direct contrast, in a rare moment of insight, his dad says something about Albie that’s surprising in its accuracy. “I think the hard thing for you, Albie… is not going to be getting what you want in life, but figuring out what that is.” I love a book that has the wherewithal to present these different sides of a single person. Such writing belies the idea that what Graff is doing here is simple.

Reading the book as a parent, I could see how my experience with Absolutely Almost was different from that of a kid reader. Take the character of Calista, for example. She’s a very sympathetic babysitter for Albie who does a lot of good for him, offering support when no one else understands. Yet she’s also just a college kid with a poorly defined sense of when to make the right and wrong choice. Spoiler Alert on the rest of this paragraph. When Albie’s suffering terribly she takes him out of school to go to the zoo and then fails to tell his parents about this executive decision on her part. A couple chapters later Albie’s mom finds out about the outing and Calista’s gone from their lives. The mom concludes that she can’t have a babysitter who lies to her and that is 100% correct. A kid reader is going to be angry with the mom, but parents, teachers, and librarians are going to be aware that this is one of those unpopular but necessary moves a parent has to face all the time. It’s part of being an adult. Sorry, kids. Calista was great, but she was also way too close to being a manic pixie dream babysitter. And trust me when I say you don’t want to have a manic pixie dream babysitter watching your children.

Remember the picture book Leo the Late Bloomer where a little tiger cub is no good at anything and then one day, somewhat magically, he’s good at EVERYTHING? Absolutely Almost is the anti-Leo the Late Bloomer. In a sense, the point of Graff’s novel is that oftentimes kindness outweighs intelligence. I remember a friend of mine in college once commenting that he would much rather that people be kind than witty. At the time this struck me as an incredible idea. I’d always gravitated towards people with a quick wit, so the idea of preferring kindness seemed revolutionary. I’m older now, but the idea hasn’t gone away. Nor is it unique to adulthood. Albie’s journey doesn’t reach some neat and tidy little conclusion by this story’s end, but it does reach a satisfying finish. Life is not going to be easy for Albie, but thanks to the lessons learned here, you’re confident that he’s gonna make it through. Let’s hope other average kids out there at least take heart from that. A hard book to write. An easy book to read.

On shelves now.

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

Other Blog Reviews:

Professional Reviews:

Other Reviews: BookPage

Interviews:

- Lisa speaks with BookPage about the creation of the book.

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 6/4/2014

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reviews,

reissues,

realistic fiction,

multicultural fiction,

abrams,

Amulet Books,

middle grade realistic fiction,

multicultural middle grade,

Tom Angleburger,

Reviews 2014,

2014 reviews,

2014 middle grade fiction,

2014 realistic fiction,

Add a tag

Here’s something I’ve never done before. For years I’ve been waiting for the moment when a book I loved and reviewed dipped out of print only to come back again. Since I’ve only been doing this gig since 2006 I wasn’t sure what that first book would be. Then, this year, I got my answer. Back in October of 2007 I reviewed a book by a newcomer going by the moniker of Sam Riddleberger. The book? The Qwikpick Adventure Society. I absolutely adored it, floored by some of the new things it was doing. Years passed and no one paid the book the appropriate amount of attention it deserved. Then Mr. Riddleberger decided to publish under his real name, Tom Angleberger, and next thing you know he’s written a little book by the name of The Strange Case of Origami Yoda and the world was never the same. What with his earlier efforts out of print and his name so incredibly bankable, I had high hopes that this might not be the last we’d seen of Mr. Riddleberger/Angleberger. Then this year, behold! Do mine eyes deceive me? No! It’s back! New cover, new title, old book.

So for today’s Flashback Wednesday we’re going to reprint that old review I did of the book . . . slightly modified. There are a couple mentions in the original review of things published “this year” that had to be updated. I’m going to keep the parts about the rarity of trailer park kids that aren’t abused, though in the comments of my original review Genevieve mentioned that The Higher Power of Lucky could be considered another alternative. Fair enough.

Enjoy!

As a children’s book reviewer there is one fact that you must keep at the forefront of your mind at all times: You are not a kid. Not usually anyway. And because you are not a kid, you are not going to read a book the way a kid does. I keep talking in my reviews about how your own personal prejudices affect your interpretation of the book in front of you, and it’s bloody true. I mean, take scatological humor in all its myriad forms. When I read How to Eat Fried Worms as an adult, I didn’t actually expect the hero to eat worms (let alone 30+ of them). And when I read Out of Patience by Brian Meehl I really enjoyed it until the moment when the local fertilizer plant became… well, you’d have to read the book to grasp the full horror of the situation. Actually, Out of Patience was the title I kept thinking of as I got deeper and deeper into The Qwikpick Papers. Both books are funny and smart and both involve gross quantities of waste to an extent you might never expect. I am an adult. I have a hard time with poop. Poop aside (and that’s saying something) there’s a lot of great stuff going on in this book. It’s definitely a keeper, though it may need to win over its primary purchasing audience, adults.

As a children’s book reviewer there is one fact that you must keep at the forefront of your mind at all times: You are not a kid. Not usually anyway. And because you are not a kid, you are not going to read a book the way a kid does. I keep talking in my reviews about how your own personal prejudices affect your interpretation of the book in front of you, and it’s bloody true. I mean, take scatological humor in all its myriad forms. When I read How to Eat Fried Worms as an adult, I didn’t actually expect the hero to eat worms (let alone 30+ of them). And when I read Out of Patience by Brian Meehl I really enjoyed it until the moment when the local fertilizer plant became… well, you’d have to read the book to grasp the full horror of the situation. Actually, Out of Patience was the title I kept thinking of as I got deeper and deeper into The Qwikpick Papers. Both books are funny and smart and both involve gross quantities of waste to an extent you might never expect. I am an adult. I have a hard time with poop. Poop aside (and that’s saying something) there’s a lot of great stuff going on in this book. It’s definitely a keeper, though it may need to win over its primary purchasing audience, adults.

Lyle Hertzog is going to level with you right from the start. In this story he and his friends, “didn’t stop a smuggling ring or get mixed up with the mob or stop an ancient evil from rising up and spreading black terror across Crickenburg.” Nope. This is the story of Lyle, Dave, and Marilla and their club’s first adventure. The kids say that they’re The Qwikpick Adventure Society because they meet regularly in the break room of the local Qwikpick convenience store where Lyle’s parents work. When it occurs to the three that they’ll all be available to hang out on Christmas Day, they decide to do something extraordinary. Something unprecedented. And when Marilla discovers that the local “antiquated sludge fountain” at the Crickenburg sewer plant is about to be replaced, they know exactly what to do. They must see the poop fountain before it is gone. The result is a small adventure that is exciting, frightening, and very very pungent.

Someone once told me that this book reminded them of Stand By Me, “except no dead bodies and no Wil Wheaton.” They may be on to something there. Author Tom Angleberger works the relationships between the kids nicely. It’s a little hard to get into the heads of all the characters considering that we’re seeing everything through Lyle’s point of view, but the author does what he can. As for the “sludge fountain” itself, kids looking for gross moments will not be disappointed. You might be able to sell it to their parents with the argument that it’s actually rather informative and factual on this point (though I suggest that you play up the relationship aspect instead).

There are few kid-appropriate taboo topics out there, but if I was going to suggest one I might say it was the issue of class. Oh, you’ll get plenty of books where a kid lives a miserable life in a trailer park and gets teased by the rich/middle class kids in their class about it, sure. Now name all the books you can think of where the main characters live in a trailer park and that’s just their life. Or have parents that work in a convenience store and there isn’t any alcohol abuse, physical abuse, emotional abuse, etc. I swear, a kid who actually lived in a trailer park these days who tried to find a book containing kids like themselves would have to assume that abuse was the norm rather than the exception. So when I saw that both Lyle and Marilla lived in a trailer park and it wasn’t a big deal, that was huge for me. Also, sometimes a book with kids of different religions or ethnicities will make a big deal about the fact. Here, Lyle’s Christian, Dave’s Jewish, and Marilla’s a Jehovah’s Witness and not white but not identified as anything in particular. Quick! Name all the Jehovah’s Witnesses you’ve encountered in children’s books where the story wasn’t ALL about being a Jehovah’s Witness! Riddleburger is making people just people. What a concept.

I’ve been talking a lot this year about books that don’t slot neatly into categories. The kinds of books that mix genres and styles. The Qwikpick Papers will be classed as fiction, no question about it, but its prolific use of photographs certainly separates it from the pack. For example, there’s a moment when the kids are trying to figure out what to do for Christmas. One of them suggests opening a fifty-gallon drum of banana puree that’s been sitting behind an empty Kroger store and there, lo and behold, is an actual honest-to-goodness photograph of a rusty, decaying, very real banana puree barrel. I don’t know whether to hope that Mr. Angleberger took the picture years ago and was just itching for a chance to get to use it, or that he created the barrel himself for the sole purpose of including a photo of it in his book. I also enjoyed the hand-drawn portions. The comic strip All-Zombie Marching Band deserves mention in and of itself (though technically William Nicholson’s The Wind Singer did it too).

I say that the poop, the sheer amount of it, will turn off a lot of adults. At the same time though there are plenty of moments that will lure the grown-ups back in again. Particularly librarians. Particularly librarians that have ever attempted an origami craft with a bunch of kids. For these brave men and women Lyle’s line about the process of doing an unfamiliar animal will ring true. “You follow the instructions through like thirty-four steps and all of a sudden there’s this funky zigzag arrow and on the next page it has turned from a lump of paper into a horse with wings.” YES! Exactly! Thank you!

All in all, I’m a fan. The characters ring true, the dialogue is snappy, the unique format will lure in reluctant readers, and talk about a title custom made for booktalking! There’s not a kid alive today who wouldn’t want to read the book when confronted with the plot. It has ups. It has downs. It has a great sense of place and a whole lot of poop. Take all angles into consideration when considering this book. On my part, I like it and that is that.

On shelves now.

Like This? Then Try:

Other Blog Reviews of the Original:

Professional Reviews of the Original: Kirkus

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 6/2/2014

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Reviews,

middle grade fiction,

Best Books,

Jacqueline Woodson,

verse novels,

multicultural fiction,

middle grade historical fiction,

fictional memoirs,

multicultural middle grade,

New York books,

middle grade verse novels,

Best Books of 2014,

Reviews 2014,

2014 reviews,

2014 middle grade fiction,

2015 Newbery contender,

2014 historical fiction,

Add a tag

brown girl dreaming

brown girl dreaming

By Jacqueline Woodson

Nancy Paulsen Books (an imprint of Penguin)

$16.99

ISBN: 978- 0399252518

Ages 9-12

On shelves August 28th

What does a memoir owe its readers? For that matter, what does a fictionalized memoir written with a child audience in mind owe its readers? Kids come into public libraries every day asking for biographies and autobiographies. They’re assigned them with the teacher’s intent, one assumes, of placing them in the shoes of those people who found their way, or their voice, or their purpose in life. Maybe there’s a hope that by reading about such people the kids will see that life has purpose. That even the most high and lofty historical celebrity started out small. Yet to my mind, a memoir is of little use to child readers if it doesn’t spend a significant fraction of its time talking about the subject when they themselves were young. To pick up brown girl dreaming by Jacqueline Woodson is to pick up the world’s best example of precisely how to write a fictionalized memoir. Sharp when it needs to be sharp, funny when it needs to be funny, and a book that can relate to so many other works of children’s literature, Woodson takes her own life and lays it out in such a way that child readers will both relate to it and interpret it through the lens of history itself. It may be history, but this is one character that will give kids the understanding that nothing in life is a given. Sometimes, as hokey as it sounds, it really does come down to your dreams.

Her father wanted to name her “Jack” after himself. Never mind that today, let alone 1963 Columbus, Ohio, you wouldn’t dream of naming a baby girl that way. Maybe her mother writing “Jacqueline” on her birth certificate was one of the hundreds of reasons her parents would eventually split apart. Or maybe it was her mother’s yearning for her childhood home in South Carolina that did it. Whatever the case, when Jackie was one-years-old her mother took her and her two older siblings to the South to live with their grandparents once and for all. Though it was segregated and times were violent, Jackie loved the place. Even when her mother left town to look for work in New York City, she kept on loving it. Later, her mother picked up her family and moved them to Brooklyn and Jackie had to learn the ways of city living versus country living. What’s more, with her talented older siblings and adorable baby brother, she needed to find out what made her special. Told in gentle verse and memory, Jacqueline Woodson expertly recounts her own story and her own journey against a backdrop of America’s civil rights movement. This is the birth of a writer told from a child’s perspective.

You might ask why we are referring to this book as a work of historical fiction, when clearly the memoir is based in fact. Recently I was reading a piece in The New Yorker on the novelist Edward St. Aubyn. St. Aubyn found the best way to recount his own childhood was through the lens of fiction. Says the man, “I wanted the freedom and the sublimatory power of writing a novel . . . And I wanted to write in the tradition which had impressed me the most.” Certainly there’s a much greater focus on what it means to be a work of nonfiction for kids in this day and age. Where in the past something like the Childhood of Famous Americans series could get away with murder, pondering what one famous person thought or felt at a given time, these days we hold children’s nonfiction to a much higher standard. Books like Vaunda Micheaux Nelson’s No Crystal Stair, for example, must be called “fiction” for all that they are based on real people and real events. Woodson’s personal memoir is, for all intents and purposes, strictly factual but because there are times when she uses dialogue to flesh out the characters and scenes the book ends up in the fiction section of the library and bookstore. Like St. Aubyn, Woodson is most comfortable when she has the most freedom as an author, not to be hemmed in by a strict structural analysis of what did or did not occur in the past. She has, in a sense then, mastered the art of the fictionalized memoir in a children’s book format.

Because of course in fiction you can give your life a form and a function. You can look back and give it purpose, something nonfiction can do but with significantly less freedom. There is a moment in Jackie’s story when you get a distinct sense of her life turning a corner. In the section “grown folks’ stories” she recounts hearing the tales of the old people then telling them back to her sister and brother in the night. “Retelling each story. / Making up what I didn’t understand / or missed when voices dropped too low . . . / Then I let the stories live / inside my head, again and again / until the real world fades back / into cricket lullabies / and my own dreams.” If ever you wanted a “birth of a writer” sequence in a book, this would be it.

At its heart, that’s really what brown girl dreaming is about. It’s the story of a girl finding her voice and her purpose. If there’s a theme to children’s literature this year it is in the relationship between stories and lies. Jonathan Auxier’s The Night Gardener and Margi Preus’s West of the Moon both spend a great deal of time examining the relationship between the two. Now brown girl dreaming joins with them. When Jackie’s mother tells her daughter that “If you lie . . . one day you’ll steal” the child cannot reconcile the two. “It’s hard to understand how one leads to the other, / how stories could ever / make us criminals.” It’s her mother that equates storytelling with lying, even as her uncle encourages her to keep making up stories. As it is, I can think of no better explanation of how writers work then the central conundrum Jackie is forced to face on her own. “It’s hard to understand / the way my brain works – so different / from everybody around me. / How each new story / I’m told becomes a thing / that happens, / in some other way / to me . . . !”

The choice to make the book a verse novel made sense in the context of Ms. Woodson’s other novels. Verse novels are at their best when they justify their form. A verse novel that’s written in verse simply because it’s the easiest way to tell a long story in a simple format often isn’t worth the paper it’s printed on. Fortunately, in the case of Ms. Woodson the choice makes infinite sense. Young Jackie is enamored of words and their meanings. The book isn’t told in the first person, but when we consider that she is both subject and author then it’s natural to suspect that the verse best shows the lens through which Jackie, the child, sees the world.

It doesn’t hurt matters any that the descriptive passages have the distinct feeling of poems to them. Individual lines are lovely in and of themselves, of course. Lines like “the heat of summer / could melt the mouth / so southerners stayed quiet.” Or later a bit of reflection on the Bible. “Even Salome intrigues us, her wish for a man’s head / on a platter – who could want this and live / to tell the story of that wanting?” But full-page written portions really do have the feel of poems. Like you could pluck them out of the book and display them and they’d stand on their own, out of context. The section labeled “ribbons” for example felt like pure poetry, even as it relayed facts. As Woodson writes, “When we hang them on the line to dry, we hope / they’ll blow away in the night breeze / but they don’t. Come morning, they’re right where / we left them / gently moving in the cool air, eager to anchor us / to childhood.” And so we get a beautiful mixing of verse and truth and fiction and memoir at once.

It was while reading the book that I got the distinct sense that this was far more than a personal story. The best memoirs, fictionalized or otherwise, are the ones that go beyond their immediate subjects and speak to something greater than themselves. Ostensibly, brown girl dreaming is just the tale of one girl’s journey from the South to the North and how her perceptions of race and self changed during that time. But the deeper you get into the book the more you realize that what you are reading is a kind of touchstone for other children’s books about the African-American experience in America. Turn to page eight and a reference to the Woodsons connections to Thomas Woodson of Chillicothe leads you directly to Jefferson’s Sons by Kimberly Brubaker Bradley. Page 32 and the trip from North to South and the deep and abiding love for the place evokes The Watsons Go to Birmingham – 1963. Page 259 and the appearance of The Jackson Five and their Afros relates beautifully to Rita Williams-Garcia’s P.S. Be Eleven. Page 297 and a reference to slaves in New York City conjures up Chains by Laurie Halse Anderson. Even Jackie’s friend Maria has a story that ties in nicely to Sonia Manzano’s The Revolution of Evelyn Serrano. I even saw threads from Woodson’s past connect to her own books. Her difficulty reading but love of words conjures up Locomotion. Visiting her uncle in jail makes me think of Visiting Day as well as After Tupac and D Foster. And, of course, her personal history brings to mind her Newbery Honor winning picture book Show Way (which, should you wish to do brown girl dreaming in a book club, would make an ideal companion piece).

It’s not just other books either. Writers are advised to write what they know and that their family stories are their history. But when Woodson writes her history she’s broadening her scope. Under her watch her family’s history is America’s history. Woodson’s book manages to tie-in so many moments in African-American history that kids should know about. Segregation, marches, Jesse Jackson, Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X. One thing I really appreciated about the book was that it also looked at aspects of some African-American life that I’ve just never seen represented in children’s literature before. Can you honestly name me any other books for kids where the children are Jehovah’s Witnesses? Aside from Tom Angleberger’s The Qwikpick Papers I’m drawing a blank.

The flaws? Well it gets off to a slow start. The first pages didn’t immediately grab me, and I have to hope that if there are any kids out there who read the same way that I do, with my immature 10-year-old brain, that they’ll stick with it. Once the family moves to the South everything definitely picks up. The only other objection I had was that I wanted to know so much more about Jackie’s family after the story had ended. In her Author’s Note she mentions meeting her father again years later. What were the circumstances behind that meeting? Why did it happen? And what did Dell and Hope and Roman go on to do with their lives? Clearly a sequel needs to happen. I don’t think I’m alone in thinking this.

I’m just going to get grandiose on you here and say that reading this is basically akin to reading a young person’s version of Song of Solomon. It’s America and its racial history. It’s deeply personal, recounting the journey of one girl towards her eventual vocation and voice. It’s a fictionalized memoir that nonetheless tells greater truths than most of our nonfiction works for kids. It is, to put it plainly, a small work of art. Everyone who reads it will get something different out of it. Everyone who reads it will remember some small detail that spoke to them personally. It’s the book adults will wish they’d read as kids. It’s the book that hundreds of thousands of kids will read and continue to read for decades upon decades upon decades. It’s Woodson’s history and our own. It is amazing.

On shelves August 28th.

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

Other Reviews: Richie’s Picks

Misc: A look at the book and an interview with Ms. Woodson from Publishers Weekly.

Videos: In this opening keynote from SLJ’s Day of Dialog in 2014, Ms. Woodson talks about the path to this book.

Jacqueline Woodson keynote | SLJ Day of Dialog 2014 from School Library Journal on Vimeo.

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 5/14/2014

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

abrams,

Amulet Books,

middle grade historical fiction,

Margi Preus,

Best Books of 2014,

Reviews 2014,

2014 reviews,

2014 middle grade fiction,

2015 Newbery contender,

2014 historical fiction,

Reviews,

middle grade fiction,

historical fiction,

Best Books,

Add a tag

West of the Moon

West of the Moon

By Margi Preus

Amulet Books (an imprint of Abrams)

$16.95

ISBN: 978-1-4197-0896-1

Ages 10 and up

On shelves now.

These are dark times for children’s literature. Pick up a book for the 9-12 year-old set and you just don’t know what you’re going to find. Whether it’s the murderous foliage of The Night Gardener, the implications of Nightingale’s Nest, or the serious subject matter of The Red Pencil, 2014 is probably best described as the year everything went dark. Don’t expect West of the Moon to lighten the mood any either. Like those books I just mentioned, it’s amazing. Dark and resilient with a core theme that simply cannot be ignored. Yet for all that Preus has tapped into a bit of harsh reality with her title that may give pause to all but the stoutest hearts. Fortunately, she tempers this reality with an artist’s license. With folktales and beautifully written prose. With a deep sisterly bond, and a serious consideration of what is right and what wrong and what is necessary in desperate circumstances. I don’t expect everyone to read this book and instantly love it, but I do expect people to read it. Slow to start, smart when it continues, and unlike anything you’ve ever really read before.

“Now I know how much I’m worth: not as much as Jesus, who I’m told was sold for thirty pieces of silver. I am worth two silver coins and a haunch of goat.” That’s Astri, discussing the fact that her aunt and uncle have just essentially sold her to Svaalberd, the local goat herder. Though she is loathe to go, she knows that she has little choice in the matter, and must leave her little sister behind with her foul relatives. Svaalberd turns out to be even fouler, however, and as she plans her escape Astri hits up on the idea of leaving Norway and going to America. With time and opportunity she makes good her plans, taking little sister Greta with her, protecting the both of them, and making difficult choices every step of the way.

I’ll just give away the game right from the start and confess to you that I’m a big time fan of this book. It’s sort of a brilliant combination of realism with folktales and writing that just cuts to the heart thanks to a heroine who is not entirely commendable (a rarity in this day and age). But I also experienced a very personal reaction to the book that as much to do with Preus’s extensive Author’s Note as anything else. You see, my own great-great-grandfather immigrated to America around the same time as Ms. Preus’s great-great-grandparents (the people who provided much of the inspiration for this book). I’ve always rather loved knowing about this fellow since most of the immigrants in my family disappeared into the past without so much as a blip. This guy we actually have photographs of. Why he left had as much to do with his abusive father as anything else, but I never really understood the true impetus behind leaving an entire country. Then I read the Author’s Note and learned about this “America fever” that spread through Norway and enticed people to leave and move to the States. It gives my own family history a bit of context I’ve always lacked and for that I thank Ms. Preus profusely.

On top of that, she provides a bit of context to the immigrant historical experience that we almost never see. We always hear about immigrants coming to America but have we ever seen a true accounting of how much food and staples they were told to bring for the boat trip? I sure as heck hadn’t! You can study Ellis Island all the livelong day but until you read about the 24 pounds of meat and the small keg of kerring folks were asked to bring, you don’t really understand what they were up against.

It should surprise no one when I say that Preus is also just a beautiful writer. I mean, she is a Newbery Honor winner after all. Still, I feel I was unprepared for the book’s great use of symbolism. Take, for example, the fact that the name of the girl that gives Astri such a hard time is “Grace”. And then there’s the fact that Preus does such interesting things with the narrative. For example she’ll mention a spell she observed Svaalberd reciting and then follow that fact up with a quick, “I’ll thank you to keep that to yourself.” You’re never quite certain whom she is addressing. The reader, obviously, but anyone else? In her Author’s Note Ms. Preus mentions that much of the book was inspired, sometimes directly, by her great-great-grandmother Linka’s diary. Knowing this, the book takes on the feel of a kind of confessional. I don’t know whom exactly Astri is confessing to, but it feels right. Plus, it turns out that she has a LOT to confess.

As characters go, Astri is a bit of a remarkable protagonist. Have you read Harriet the Spy recently? See, back in the day authors weren’t afraid to write unsympathetic main characters. People that you rooted for, but didn’t particularly like. But recent children’s literature shies away from that type. Our protagonists are inevitably stouthearted and true and if they do have flaws then they work through them in a healthy all-American kind of way. Astri’s different. When she recounts her flaws they take on the feeling of a folktale (“I’ve stolen the gold and hacked off the fingers and snitched the soap and swiped the wedding food. I’ve lied to my own little sister and left Spinning Girl behind, and now I’m stealing the horse, saddle, and bridle from the farm boy who never did anything wrong except display a bit of greed.”) But hey, she’s honest! This section is then followed with thoughts on what makes a person bad. Does desperation counteract sin? How do you gauge individual sins?

If I’ve noted any kind of a theme in my middle grade children’s literature this year (aside from the darkness I alluded to in the opening paragraph) it’s a fascination with the relationship between lies and stories. Jonathan Auxier explored this idea to some extent in The Night Gardener, as did Jacqueline Woodson in Brown Girl Dreaming. Here, Preus returns to the notion of where stories stop and lies begin again and again. Says she at some point, “soon I’ve run out of golden thread with which to spin my pretty stories and I’m left with just the thin thread of truth.” Astri is constantly telling stories to Gerta, sometimes to coax her into something, sometimes to comfort her. But in her greatest hour of soul searching she wonders, “Is it a worse sin to lie to my sweet sister than to steal from a cruel master?” And where does lying start when storytelling ends? There are no easy answers to be found here. Just excellent questions.

So let’s talk attempted sexual assault in a work of children’s literature. Oh, it’s hardly uncommon. How many of us remember the reason that Julie in Julie of the Wolves ran away to join a furry pack? In the case of West of the Moon the attempt could be read any number of ways. Adults, for example, will know precisely what is going on. But kids? When Astri sees her bed for the first time she takes the precaution of grabbing the nearest knife and sticking it under her pillow. No fool she, and the act turns out to be a good piece of forethought since later in the book the goatman does indeed throw her onto her bed. She comes close to cutting his jugular and the incident passes (though he says quite clearly, “Come summer, we will go down to the church and have the parson marry us. Then I’ll take you to my bed.”). Reading the section it’s matter-of-fact. A realistic threat that comes and goes and will strike a chord with some readers instantly and others not at all. There will be kids that read the section and go to their parents or teachers (or even librarians) looking for some clarification, so adults who hand this to younger readers should be ready for uncomfortable questions. Is it inappropriate for kids? That is going to depend entirely on the kid. For some 9 and 10-year-olds there’s nothing here to raise an eyebrow. Astri hardly does. Later she hates the goatman far more for baby lambicide than any attempted rape. For others, they’ll not care for the content. Kids are great self-censors, though. They know what they can handle. I wouldn’t be worried on that score.

If we’re going to get to the heart of the matter, this book is about grace and forgiveness. It’s about how even victims (or maybe especially victims) are capable of terrible terrible things. It’s about making amends with the world and finding a way to forgive yourself and to move on. Astri is, as I’ve said before, not a saintly character. She steals and tricks good people for her own reasons and she leaves it to the reader to decide if she is worth forgiving. This is an ideal book discussion title, particularly when you weave in a discussion of the folktales, the notion of stories vs. lies, and the real world history. It’s not an easy book and it requires a little something extra on the part of the reader, but for those kids that demand a bit of a challenge and a book that’ll make ‘em stop and think for half a moment, you can’t do better. Remarkable.

On shelves now.

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

- The Sea of Trolls by Nancy Farmer – Few can weave folktales into text as well as Farmer, so naturally when I saw what Preus was doing here I thought of this epic series.

- The Carnivorous Carnival by Lemony Snicket – Because if anyone understands how to bring up the notion of whether or not sinking to the level of the bad guys makes YOU a bad guy, it’s Snicket. And this was the first book in A Series of Unfortunate Events to come up with the notion.

- The Night Gardener by Jonathan Auxier – These two books wouldn’t have a lot in common were it not for the fact that Auxier delves into the relationship between lies and stories as deeply as Preus and with similar conclusions.

Other Blog Reviews:

Professional Reviews:

Interviews: KUMD spoke with Ms. Preus about her books and her work on this one in particular here.

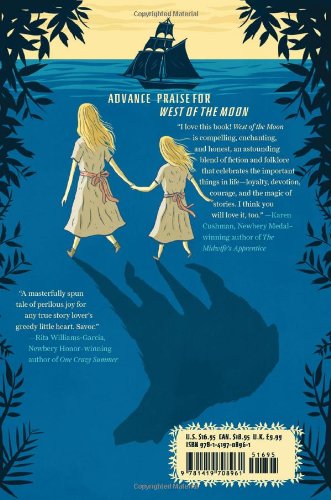

Book Jacket: Oo! In case you didn’t get to see the back cover . . .

Misc: For a look behind-the-scenes of the book check out this article Award-winning Duluth author pulls from folk tales, ancestral diary for newest novel from the Duluth News Tribune.

Videos: And here’s the book trailer!

West of the Moon / Margi Preus Book Trailer from Joellyn Rock on Vimeo.

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 3/31/2014

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Penguin,

Best Books,

Dial Books for Young Readers,

middle grade historical fiction,

Gary Blackwood,

Best Books of 2014,

Reviews 2014,

2014 reviews,

2014 middle grade fiction,

2015 Newbery contender,

2014 historical fiction,

Reviews,

middle grade fiction,

historical fiction,

Add a tag

Curiosity

Curiosity

By Gary Blackwood

Dial (an imprint of Penguin Young Readers Group)

$16.99

ISBN: 978-0-8037-3924-6

Ages 9-12

On shelves April 10th

Blackwood’s back, baby! And not a minute too soon. Back in 1998, the author released The Shakespeare Stealer which would soon thereafter become his best-known work. A clever blending of historical fiction and adventure, the book allowed teachers the chance to hone Shakespeare down to a kid-friendly level. Since its publication Mr. Blackwood has kept busy, writing speculative fiction and, most recently, works of nonfiction for kids. Then there was a bit of a lull in his writing and the foolish amongst us (myself included) forgot about him. There will be no forgetting Mr. Blackwood anytime now though. Not after you read his latest work Curiosity. Throwing in everything from P.T. Barnum and phrenology to hunchbacks, Edgar Allan Poe, automatons, chess prodigies, murder, terrible fires, and legless men, Blackwood produces a tour de force to be reckoned with. In the press materials for this book, Penguin calls it “Gary Blackwood’s triumphant return to middle grade fiction.” They’re not wrong. The man’s about to acquire a whole new generation of fans and enthusiasts.

Fear for the children of novels that describe their childhoods as pampered or coddled. No good can come of that. Born weak with a slight deformity of the spine, Rufus lives a lovely life with his father, a well-respected Methodist minister in early 19th century Philadelphia. That’s all before his father writes a kind of predecessor to The Origin of the Species and through a series of misadventures is thrown into debtor’s prison. Fortunately (perhaps) Rufus is a bit of a chess prodigy and his talents get him a job with a man by the name of Johann Nepomuk Maelzel. Maelzel owns an automaton called The Turk that is supposed to be able to play chess against anyone and win. With Rufus safely ensconced inside, The Turk is poised to become a massive moneymaker. But forces are at work to reveal The Turk’s secrets and if that information gets out, Rufus’s life might not be worth that of the pawns he plays.

Making the past seem relevant and accessible is hard enough when you’re writing a book for adults. Imagine the additional difficulty children’s authors find themselves in. Your word count is limited else you lose your audience. That means you need to engage in some serious (not to mention judicious and meticulous) wordplay. Blackwood’s a pro, though. His 1835 world is capable of capturing you with its life and vitality without boring you in the process. At one point Rufus describes seeing Richmond, VA for the first time and you are THERE, man. From the Flying Gigs to the mockingbirds to the James River itself. I was also relieved to find that Blackwood does make mention of the African-Americans living in Richmond and Philly at the time this novel takes place. Many are the works of historical fiction by white people about white people that conveniently forget this little fact.

Add onto that the difficulty that comes with making the past interesting and accurate and relevant all at once. I read more historical fiction for kids than a human being should, and while it’s all often very well meaning, interesting? Not usually an option. I’m certain folks will look at how Blackwood piles on the crazy elements here (see: previous statement about the book containing everything from phrenology to P.T. Barnum) and will assume that this is just a cheap play for thrills. Not so. It’s the man’s writing that actually holds your focus. I mean, look at that first line: “Out of all the books in the world, I wonder what made you choose this one.” Heck, that’s just a drop in the bucket. Check out these little gems:

“If my cosseted childhood hadn’t taught me how to relate to other people, neither had it taught em to fear them.”

“I was like some perverse species of prisoner who felt free only when he was locked inside a tiny cell.”

“Maelzel was not the sort of creator imagined by the Deists, who fashions a sort of clockwork universe and winds it up, then sits back and watches it go and never interferes. He was more like my father’s idea of the creator: constantly tinkering with his creations, looking for ways to make them run more smoothly and perform more cleverly – the kind who makes it possible for new species to develop.”

As for the writing of the story itself, Blackwood keeps the reader guessing and then fills the tale with loads of historical details. The historical accuracy is such that Blackwood even allows himself little throwaway references, confident that confused kids will look them up themselves. For example, at one point Rufus compares himself to “Varney the Vampire climbing into his coffin.” This would be a penny dreadful that circulated roundabout this time (is there any more terrifying name than “Varney” after all?). In another instance a blazing fire is met with two “rival hose” companies battling one another “for the right to hook up to the nearest fireplug.” There is a feeling that for a book to be literary it has to be dull. Blackwood dispels the notion, and one has to stand amazed when they realize that somehow he managed to make a story about a kid trapped in a small dark space for hours at a time riveting.

Another one of the more remarkable accomplishments of the book is that it honestly makes you want to learn more about the game of chess. A good author can get a kid interested in any subject, of course. I think back on The Cardturner by Louis Sachar, which dared to talk up the game of Bridge. And honestly, chess isn’t a hard sell. The #1 nonfiction request I get from my fellow children’s librarians (and the request I simply cannot fulfill fast enough) is for more chess books for kids. At least in the big cities, chess is a way of life for some children. One hopes that we’ll be able to extend their interest beyond the immediate game itself and onto a book where a kid like themselves has all the markings of true genius.

It isn’t perfect, of course. In terms of characterization, of all the people in this book Rufus is perhaps the least interesting. You willingly follow him, of course. Just because he doesn’t sparkle on the page like some of the other characters doesn’t mean you don’t respond to the little guy. One such example might be when his first crush doesn’t go as planned. But he’s a touchstone for the other characters around him. Then there’s the other problem of Rufus being continually rescued by the same person in the same manner (I won’t go into the details) more than once. It makes for a weird repeated beat. The shock of the first incident is actually watered down by the non-surprise of the second. Rufus becomes oddly passive in his own life, rarely doing anything to change the course of his fate (he falls unconscious and wakes up rescued more than once,) a fact that may contribute to the fact that he’s so unmemorable on the page.

But that aside, it’s hard not to be entranced by what Blackwood has come up with here. Automatons sort of came to the public’s attention when Brian Selznick wrote The Invention of Hugo Cabret. Blackwood takes it all a step further merging man and machine, questioning what we owe to one another and, to a certain extent, where the power really lies. Rufus finds his sense of self and bravery by becoming invisible. At the same time, he’s so innocent to the ways of the world that becoming visible comes with the danger of having your heart broken in a multitude of different ways. In an era where kids spend untold gobs of time in front of the screens of computers, finding themselves through a newer technology, Blackwood’s story has never been timelier. Smart and interesting, fun and strange, this is one piece of little known history worthy of your attention. Check and mate.

On shelves April 10th.

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

First Line: “Out of all the books in the world, I wonder what made you choose this one.”

Notes on the Cover: And now let us praise fabulous cover artists. Particularly those creating covers that make more sense after you’ve finished the book. The glimpse of Rufus’s eye in the “O” of the title didn’t do much more than vaguely remind me of the spine of the The Invention of Hugo Cabret at first (an apt comparison in more than one way). After closer examination, however, I realized that it was Rufus in the cabinet below. The unnerving view of The Turk and the shadowy Mr. Hyde-ish man in the far back all combine to give this book a look of both historical fervor and intrigue. And look how that single red (red?) pawn is lit. It’s probably not actually a red pawn but a white one, but something about the image looks reddish. Blood red, if you will. Boy, that’s a good jacket.

Professional Reviews: A star from Kirkus

Misc:

- Care to read Edgar Allan Poe’s actual article for The Messenger about The Turk? Do so here.

- A fun BBC piece on the implication of The Turk then, now, and for our children. It appears to have been written by one “Adam Gopnik”. We’ll just assume it’s a different Adam than the one behind A Tale Dark & Grimm.

Videos: Want to see the real Turk in action? This video makes for fascinating watching.

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 3/12/2014

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Jonathan Auxier,

Best Books of 2014,

Reviews 2014,

2014 reviews,

2014 middle grade fiction,

2015 Newbery contender,

2014 fantasy,

middle grade historical fantasy,

Reviews,

middle grade fantasy,

Best Books,

abrams,

Amulet Books,

Patrick Arrasmith,

historical fantasy,

Add a tag

The Night Gardener

The Night Gardener

By Jonathan Auxier

Illustrated by Patrick Arrasmith

Amulet Books (an imprint of Abrams)

$16.95

ISBN: 978-1-4197-1144-2

Ages 10 and up

On shelves May 20th

For whatever reason, 2014 is a dark year in children’s middle grade fiction. I speak from experience. Fantasy in particular has been steeped in a kind of thoughtful darkness, from The Glass Sentence and The Thickety to The Riverman and Twelve Minutes to Midnight with varying levels of success. And though none would contest the fact that they are creepy, only Jonathan Auxier’s The Night Gardener has had the chutzpah to actually write, “A Scary Story” on its title pages as a kind of thoughtful dare. A relatively new middle grade author, still young in the field, reading this book it’s hard to reconcile it with Auxier’s previous novel Peter Nimble and His Fantastic Eyes. It is almost as if Mr. Auxier took his whimsy, pulled out a long sharp stick, and stabbed it repeatedly in the heart and left it to die in the snow so as to give us a sublimely horrific little novel. Long story short this novel is Little Shop of Horrors meets The Secret Garden. I hope I’m not giving too much away by saying that. Even if I am, I regret nothing. Here we have a book that ostensibly gives us an old-fashioned tale worthy of Edgar Allan Poe, but that steeps it in a serious and thought provoking discussion of the roles of both lies and stories when you’re facing difficulties in your life. Madcap brilliant.

Molly and Kip are driving a fish cart, pulled by a horse named Galileo, to their deaths. That’s what everyone’s been telling them anyway. Living without parents, Molly sees herself as her brother’s guardian and is intent upon finding a safe place for the both of them. When she’s hired to work as a servant at the mysterious Windsor estate she thinks the job might be too good to be true. Indeed, the place (located deep in something called “the sour woods”) is a decrepit old mansion falling apart at the seams. The locals avoid it and advise the kids to do so too. Things are even stranger inside. The people who live in the hollow home appear to be both pale and drawn. And it isn’t long before both Molly and Kip discover the mysterious night gardener, who enters the house unbidden every evening, tending to a tree that seems to have a life of its own. A tree that can grant you your heart’s desire if you would like. And all it wants in return? Nothing you’d ever miss. Just a piece of your soul.

For a time, the book this most reminded me of was M.P. Kozlowsky’s little known Juniper Berry, a title that could rival this one in terms of creepiness. Both books involve trees and wishes and souls tied into unlawful bargains with dark sources. There the similarities end, though. Auxier has crafted with undeniable care a book that dares to ask whether or not the things we wish for are the things best for us in the end. His storytelling works in large part too because he gives us a unique situation. Here we have two characters that are desperately trying to stay in an awful, dangerous situation by any means necessary. You sympathize with Molly’s dilemma at the start, but even though you’re fairly certain there’s something awful lurking beneath the surface of the manor, you find yourself rooting for her, really hoping that she gets the job of working there. It’s a strange sensation, this dual hope to both save the heroine and plunge her into deeper danger.

What really made The Night Gardener stand out for me, however, was that the point of the book (insofar as I could tell) was to establish storytelling vs. lies. At one point Molly thinks seriously about what the difference between the two might be. “Both lies and stories involved saying things that weren’t true, but somehow the lies inside the stories felt true.” She eventually comes to the conclusion that lies hurt people and stories help them, a statement that is met with agreement on the part of an old storyteller named Hester who follows the words up with, “But helps them to do what?” These thoughts are continued later when Molly considers further and says, “A story helps folks face the world, even when it frightens ‘em. And a lie does the opposite. It helps you hide.” Nuff said.

As I mentioned before, Auxier’s previous novel Peter Nimble and His Fantastic Eyes was his original chapter book debut. As a devotee of Peter Pan and books of that ilk, it felt like more of an homage at times that a book that stood on its own two feet. In the case of The Night Gardener no such confusion remains. Auxier’s writing has grown some chest hair and put on some muscles. Consider, for example, a moment when Molly has woken up out of a bad dream to find a dead leaf in her hair. “Molly held it up against the window, letting the moonlight shine through its brittle skin. Tiny twisted veins branched out from the center stem – a tree inside a tree.” I love the simplicity of that. Particularly when you take into account the fact that the tree that created the leaf may not have been your usual benign sapling.

In the back of the book in his Author’s Note Auxier acknowledges his many influences when writing this. Everything from Ray Bradbury’s Something Wicked This Way Comes to The Sketch-Book of Geoffrey Crayon Gent. by Washington Irving to Frances Hodgson Burnett’s simple only on the surface The Secret Garden. All these made sense to me (though I’m not familiar with the Irving yet) but I wondered if there were other ties out there as well. For example, the character of Hester, an old storyteller and junk woman, reminded me of nothing so much as the junk woman character in the Jim Henson film Labyrinth. A character that in that film also straddles the line between lies and stories and how lying to yourself only does you harm. Coincidence or influence? Only Mr. Auxier knows for sure.

If I am to have any kind of a problem with the book then perhaps it is with the Irish brogue. Not, I should say, that any American child is even going to notice it. Rather, it’ll be adults like myself that can’t help but see it and find it, ever so briefly, takes us out of the story. I don’t find it a huge impediment, but rather a pebble sized stumbling block, barely standing in the way of my full enjoyment of the piece.

In Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, J.K. Rowling offers some very good advice on dealing with uncertain magical beings. “Never trust anything that can think for itself if you can’t see where it keeps its brain.” Would that our heroes in this book had been handed such advice early in life, but then I guess we wouldn’t have much of a story to go on, now would we? In the end, the book raises as many questions as it answers. Do we, as humans, have an innate fear of becoming beholden to the plants we tend? Was the villain of the piece’s greatest crime to wish away death? Maybe the Peter Pan influence still lingers in Mr. Auxier’s pen, but comes out in unexpected ways. This is the kind of book that would happen if Captain Hook, a man most afraid of the ticking of a clock, took up horticulture instead of piracy. But the questions about why we lie to ourselves and why we find comfort in stories are without a doubt the sections that push this book from mere Hammer horror to horror that makes you stop and think, even as you run like mad to escape the psychopaths on your heels. Smart and terrifying by turns, hand this book to the kid who supped of Coraline and came back to you demanding more. Sweet creepy stuff.

On shelves May 20th.

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

Professional Reviews: A star from Kirkus

By:

Betsy Bird,

on 2/28/2014

Blog:

A Fuse #8 Production

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Nikki Loftin,

Best Books of 2014,

Reviews 2014,

2014 reviews,

2014 middle grade fiction,

2015 Newbery contender,

middle grade magical realism,

Reviews,

middle grade fiction,

Penguin,

Best Books,

Razorbill,

magical realism,

Add a tag

Nightingale’s Nest

Nightingale’s Nest

By Nikki Loftin

Razorbill (an imprint of Penguin)

$16.99

ISNB: 978-1-59514-546-8

Ages 10-14

On shelves now.

Magical realism in children’s novels is a rarity. It’s not unheard of, but when children’s authors want fantasy, they write fantasy. When they want reality, they write reality. A potentially uncomfortable mix of the two is harder to pull off. Ambiguity is not unheard of in books for youth, but it’s darned hard to write. Why go through all that trouble? For that reason alone we don’t tend to see it in children’s books. Kids like concrete concepts. Good guys vs. bad guys. This is real vs. this is a dream. But a clever author, one who respects the intelligence of their young audience, can upset expectations without sacrificing their story. When author Nikki Loftin decided to adapt Hans Christian Andersen’s tale The Nightingale into a middle grade contemporary novel, she made a conscious decision to make the book a work of magical realism. A calculated risk, Loftin’s gambit pays off. Nightingale’s Nest is a painful but ultimately emotionally resonant tale of sacrifice and song. A remarkably competent book, stronger for its one-of-a-kind choices.

It doesn’t seem right that a twelve-year-old boy would carry around a guilt as deep and profound as Little John’s. But when you feel personally responsible for the death of your little sister, it’s hard to let go of those feelings. It doesn’t help matters any that John has to spend the summer helping his dad clear brush for the richest man in town, a guy so extravagant, the local residents just call him The Emperor. It’s on one of these jobs that John comes to meet and get to know The Emperor’s next door neighbor, Gayle. About the age of his own sister when she died, Gayle’s a foster kid who prefers sitting in trees in her own self-made nest to any other activity. But as the two become close friends, John notices odd things about the girl. When she sings it’s like nothing you’ve ever heard before, and she even appears to possibly have the ability to heal people with her voice. It doesn’t take long before The Emperor becomes aware of the treasure in his midst. He wants Gayle’s one of a kind voice, and he’ll do anything to have it. The question is, what does John think is more important: His family’s livelihood or the full-throated song of one little girl?

How long did it take me to realize I was reading a middle grade adaptation of a Hans Christian Andersen short story? Let me first tell you that when I read a book I try not to read even so much as a plot description beforehand so that the novel will stay fresh and clear in my mind. With that understanding, it’s probably not the worst thing in the world that it took a 35-year-old woman thirty-nine pages before she caught on to what she was reading. Still, I have the nasty suspicion that many a savvy kid would have picked up on the theme before I did. As it stands, we’ve seen Andersen adapted into middle grade novels for kids before. Breadcrumbs, for example, is a take on his story The Snow Queen as well as some of his other, stranger tales. They say that he wrote The Nightingale for the singer Jenny Lind, with whom he was in love. All I know is that in the original tale the story concentrates on the wonders of the natural world vs. the mechanical one. In this book, Loftin goes in a slightly different direction. It isn’t an over-reliance on technology that’s the problem here. It’s an inability to view our fellow human beings as just that. Human beings. Come to think of it, maybe that’s what Andersen was going for in the first place.

It was the writing, of course, that struck my attention first. Loftin gives the book beautiful sequences filled with equally beautiful sentences. There’s a section near the end that tells a tale of a tree that fails to keep hold of a downy chick, but is redeemed by saving another bird in a storm. This section says succinctly everything you need to know about this book. I can already see the children’s book and discussion groups around the country that will get a kick out of picking apart this parable. It’s not a hard one to interpret, but you wouldn’t want it to be.