By Anatoly Liberman

Last time I was writing my monthly gleanings in anticipation of the New Year. January 1 came and went, but good memories of many things remain. I would like to begin this set with saying how pleased and touched I was by our correspondents’ appreciation of my work, by their words of encouragement, and by their promise to go on reading the blog in the future. Writing weekly posts is a great pleasure. Knowing that one’s voice is not lost in the wilderness doubles and trebles this pleasure.

Week and Vikings.

After this introduction it is only natural to begin the first gleanings of 2013 with the noun week. Quite some time ago, I devoted a special post to it. Later the root of week turned up in the post on the origin of the word Viking, and it was Viking that made our correspondent return to week. My ideas on the etymology of week are not original. In the older Germanic languages, this noun did not mean “a succession of seven days.” The notion of such a unit goes back to the Romans and ultimately to the Jewish calendar. The Latin look-alike of Gothic wiko, Old Engl. wicu, and so forth was a feminine noun, whose nominative, if it existed, must have had the form vix. Since the phrase for “in the order of his course” (Luke I: 8) appears in Latin as in ordine vicis suae and in Gothic as in wikon kunjis seinis, some people (the great Icelandic scholar Guðbrandur Vigfússon among them) made the wrong conclusion that the Germanic word was borrowed from Latin. In English, the root of vix can be seen in vicar (an Anglo-French word derived from Latin vicarius “substitute, deputy”), vicarious, vicissitude, vice (as in Vice President), and others, while week is native. Its distant origin is disputed and need not delay us here. Rather probably, German Wechsel (from wehsal) “exchange” belongs here. Among the old cognates of week we find Old Icelandic vika, which also had the sense “sea mile,” and this is where Viking may come in. “Change, succession, recurrent period” and “sea mile” suggest that the oldest Vikings (in the beginning, far from being sea robbers and invaders) were called after “shift, a change of oarsmen.” But many other hypotheses pretend to explain the origin of Viking, and a few of them are not entirely implausible.

The present perfect.

More recently, while discussing suppletive forms, I mentioned in passing that the difference between tenses can become blurred and that for some people did you put the butter in the refrigerator? and have you put the butter in the refrigerator? mean practically the same. This remark inspired two predictable comments. The vagaries of the present perfect also turned up in one of my recent posts and also caused a ripple of excitement, especially among the native speakers of Swedish. As with week and Viking, I’ll repeat here only my basic explanation. In Germanic, the perfect tenses developed in the full light of history, and in British English a good deal seems to have changed since the days of Shakespeare, that is, the time when the first Europeans settled in the New World. To put it in a nutshell, there was much less of the present perfect in the sixteenth and the seventeenth century than in the nineteenth. In the use of this tense English, wherever it is spoken, went its own way. For instance, one can say in Icelandic (I’ll provide a verbatim translation): “We spent a delightful summer together in 1918, and at that time we have seen so many interesting places together!” The perfect foregrounds the event and makes it part of the present. In English, the present perfect cannot be used so. Only a vague reference to the days gone by will tolerate the present perfect, as in: “This has happened more than once in the past and is sure to happen again.” Therefore, I was surprised to see Cuthbert Bede (alias Edward Bradley) write in The Adventures of Mr Verdant Green: “Who knows? for dons are also mortals, and have been undergraduates once” (the beginning of Chapter 4). In my opinion, have been and once do not go together. If I am wrong, please correct me.

However, in my next pronouncement I am certainly right. British English has regularized the use of the present perfect: “I have just seen him,” “I have never read Fielding,” and so on. I mentioned in my original post that, when foreigners are taught the difference between the simple past (the so-called past indefinite) and the present perfect, they are usually shown a picture of a weeping or frightened child looking at the fragments on the floor and complaining to a grownup: “I have broken a plate!” American speakers are not bound by this usage: “I just saw him. He left,” “I never read Fielding and know no one who did,” while a child would cry: “Mother, I broke a plate!” A British mother may be really cross with the miscreant, whereas an American one may be mad at the child, but their reaction has nothing to do with grammar. Our British correspondent says that he makes a clear distinction between did you and have you put the butter in the refrigerator, while his American wife does not and prefers did you. This is exactly what could be expected. My British colleague, who has not changed his accent the tiniest bit after decades of living in Minneapolis and being married to an American, must have unconsciously modified his usage. I have been preoccupied with the perfect for years, and once, when we were discussing these things, he said, with reference to the present perfect, that during his recent stay in England, his interlocutor remarked drily: “You have lived in America too long.”

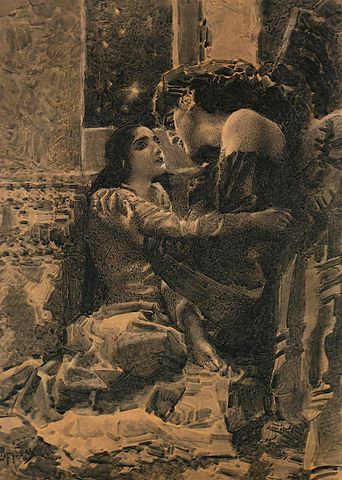

Blessedly cursed? Tamara and Demon. Ill to Lermontov’s poem by Mikhail Vrubel’, 1890. (Tretiakov gallery.) Demon and Tamara are the protagonists in the poem by Mikhail Lermontov (1814-1841). The poem is famous in Russia; there is an opera on its plot; several translations into English, including one by Anatoly Liberman, exist; and Vrubel’ was obsessed by this work.

In discussing suppletive forms (go/went, be/am/is/are, and others), I wrote that, although we have pairs like actor/actress and lion/lioness, we are not surprised that boy and girl are not derived from the same root. I should have used a more cautious formulation. First, I was asked about man and woman. Yes, it is true that woman goes back to wif-man, but, in Old English, man meant “person,” while “male” was the result of later specialization, just as in Middle High German man had the senses “man, warrior, vassal,” and “lover.” Wifman meant “female person.” The situation is more complicated with boys and girls. Romance speakers will immediately remember (as did our correspondent, a native speaker of Portuguese) Italian fanciullo (masculine) ~ fanciulla (feminine) and the like. In Latin, such pairs also existed (puellus and puella). But I don’t think that fanciulla and puella were formed from funciullo and puellus: they are rather parallel forms. But I am grateful for being reminded of such pairs; they certainly share the same root.

Lewis Carroll’s name.

I think the information provided by Stephen Goranson is sufficient to conclude that the Dodgson family pronounced their family name as Dodson, and this confirms my limited experience with the people called Dodgson and Hodgson.

PS. At my recent talk show on Minnesota Public Radio, which was devoted to overused words, I received a long list of nouns, adjectives, and verbs that our listeners hate. I will discuss them and answer more questions next Wednesday. But one question has been sitting on my desk for two months, and I cannot find any information on it. Here is the question: “I was wondering if you knew what the Latin and Italian translations would be of the term blessedly cursed? I know this is not a common phrase, but I would think that there would be a translation for it.” Latin is tough, but our correspondents from Italy may know the equivalent. Their help will be greatly appreciated.

To be continued.

Anatoly Liberman is the author of Word Origins…And How We Know Them as well as An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction. His column on word origins, The Oxford Etymologist, appears here, each Wednesday. Send your etymology question to him care of [email protected]; he’ll do his best to avoid responding with “origin unknown.”

Subscribe to Anatoly Liberman’s weekly etymology posts via email or RSS.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Monthly etymology gleanings for January 2013, part 1 appeared first on OUPblog.