By Arthur P. Shimamura

This year’s academy award nominations of Argo, Lincoln, and Zero Dark Thirty, attest to our fascination of watching “true stories” depicted on the screen. We adopt a special set of expectations when we believe a movie is based on actual events, a sentiment the Coen Brothers parodied when they stated at the beginning of Fargo that “this is a true story,” even though it wasn’t. In the science fiction spoof, Galaxy Quest, aliens have intercepted a Star Trek-like TV show and believe the program to be a documentary of actual human warfare. As a result, they come to Earth to enlist Cmdr. Peter Quincy Taggart (Tim Allen), star of the TV show, to help fight the evil warlord Sarris (named after the film critic, Andrew Sarris), as they believe Taggart to be a true war hero rather than merely playing one on TV.

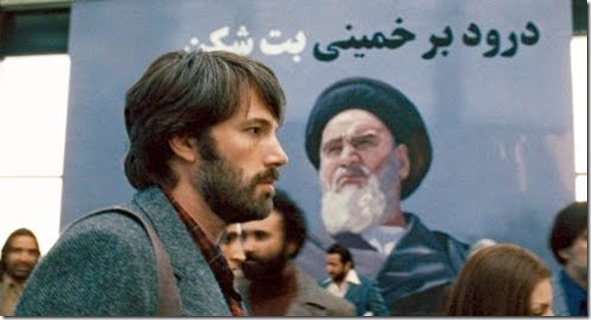

Ben Affleck in Argo. (c) 2012 Warner Bros.

Movies that are “based on a true story” blur the boundary between documentary and make-believe. We, much like the aliens in

Galaxy Quest, expect such movies to depict an authentic portrayal of actual events. The story of

Argo — about a CIA agent who helps individuals escape from Iran by having them pose as a film crew — would almost have to be based on actual events, otherwise no one would buy into such a preposterous plot! Interestingly, the climatic chase scene on the airport runway is completely fictional, though I think we forgive the filmmakers for some poetic license, particularly as the scene is so exciting. We are much less forgiving in the portrayal of torture in

Zero Dark Thirty, to the point where producer Mark Boal and director Kathryn Bigelow have been reprimanded by Senators Feinstein, Levin, and McCain for suggesting that torture was effective in the hunt for Osama bin Laden. Yet even documentaries distort the “truth” by slanting history through biased portrayals. Should movies “based on a true story” be viewed as completely accurate documents of history?

One psychological point is clear: our emotional involvement with a movie depends on the degree to which we expect or “appraise” the events to be real. Studies by Richard Lazarus and others have shown that physiological markers of emotion, such as skin conductance (i.e. sweaty palms), increase when subjects believe a film to depict an actual event. In one study, subjects watched a film clip depicting an industrial accident involving a power saw. Those who were told that they were watching footage of an actual accident (rather than actors re-enacting the event) exhibited heightened emotional responses. Thus, people watching the same movie may engage themselves differently depending on the degree to which they construe the events as realistic portrayals.

Even when we know we are watching a re-enactment, as with Argo, Lincoln, and Zero Dark Thirty, I suspect we become more emotionally attached when we believe we are witnessing actual events. We more readily empathize with characters and buy into the story. Of course, the authenticity of a movie depends not only on us having prior knowledge that a movie is based on actual events but also on how realistic the characters appear in their actions and predicaments. As wonderfully realistic and engaging as Argo, Lincoln, and Zero Dark Thirty were, in my opinion the most “realistic” movie among this year’s Academy Award nominees is the entirely fictitious Amour, in which the elderly Georges (Jean-Louis Trintignant) must care for his wife (Emmanuelle Riva), whose mental abilities are deteriorating from strokes. The superb acting and unusual editing (e.g. exceedingly long takes) amplify emotions and engage us as if we are watching a true and heart-wrenching story.

Arthur P. Shimamura is Professor of Psychology at the University of California, Berkeley and faculty member of the Helen Wills Neuroscience Institute. He studies the psychological and biological underpinnings of memory and movies. He was awarded a John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship in 2008 to study links between art, mind, and brain. He is co-editor of Aesthetic Science: Connecting Minds, Brains, and Experience (Shimamura & Palmer, ed., OUP, 2012), editor of the forthcoming Psychocinematics: Exploring Cognition at the Movies(ed., OUP, March 2013), and author of the forthcoming book, Experiencing Art: In the Brain of the Beholder (May 2013). Further musings can be found on his blog, Psychocinematics: Cognition at the Movies.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only television and film articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Image used for the purpose of illustrating the work in question.

The post Based on a “true” story: expecting reality in movies appeared first on OUPblog.

By Arthur P. Shimamura

Is it the sense of experiencing reality that makes movies so compelling? Technological advances in film, such as sound, color, widescreen, 3-D, and now high frame rate (HFR), have offered ever increasing semblances of realism on the screen. In The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey, we are introduced to the world of 48 frames per second (fps), which presents much sharper moving images than what we’ve seen in movies produced at the standard 24 fps. Yet many viewers, including myself, have come away with a less-than-satisfying experience as the sharp rendering of the characters portrayed is reminiscent of either old videotaped TV programs (soap operas, BBC productions) or recent CGI video games. What features of HFR create this new sensory experience and why does it appear so unsettlingly similar to the experience of watching a low budget TV program?

One factor that can be ruled out is the potential difference in flicker rate. Moving images are of course created by the rapid succession of still frames, and thus the flicker or on-and-off rate must be fast enough so that we do not perceive any change in illumination between frames. With early silent films, the flicker rate was less than 16 fps, and a noticeable flashing or flickering was apparent (hence the term “flicks” to refer to these early movies). Since the advent of sound, the standard has been 24 fps, though the flicker rate is increased with the use of a propeller-like shutter that spins rapidly in a movie projector so that a movie running at 24 fps actually presents each frame two or three times, thereby increasing the flicker rate to 48 or 72 fps. Thus, with respect to flicker rate we have always watched movies at HFR.

A still from The Hobbit film. (c) Warner Bros.

Two factors have motivated the current interest in HFR. The obvious one is that actions recorded at more rapid frame rates, such as a car chase shot at 48 fps vs 24 fps, would reduce by half the distance objects move across successive frames. With HFR we are presented shorter increments of movement, and our brains need not work as hard to extrapolate apparent motion across frames, which may result in a smoother sense of motion. I, however, do not think that it is this between-frame difference that is driving our sensory experience as we watch The Hobbit. A second, less known factor, is that the movie was shot at a faster shutter speed than movies shot at 24 fps. Filmmakers have a rule that states that the shutter speed at which each frame is shot should be half as long as the frame duration. Thus, most movies we’ve seen have been shot at 24 fps with a shutter speed of 1/48 sec for each frame. Those of you who have played with photography know that this shutter speed would produce rather blurry images when the camera is hand held. On a tripod, a movie filmed with this shutter speed would show fast moving objects (e.g., cars) with a noticeable blur. When movies filmed at 24 fps are shot with a faster shutter speed and less motion blur, actions appear jerky and unnatural.

The Hobbit was filmed with a shutter speed of 1/64 sec, which produced less motion blur and thus sharper images compared to movies shot at 24 fps. At the faster frame rate, the jerkiness associated with presenting sharp images at 24 fps is largely reduced, though I did notice that on some occasions large camera movements and fast movements of actors appeared stilted and unnatural. A psychological study by Kuroki and colleagues showed that in order to perceive naturalistic movements with sharp moving images (i.e., no motion blur) it is necessary to use frame rates of 250 fps or faster. Interestingly, the shutter speed used for The Hobbit closely matches that used for old videotaped TV programs, which were filmed at 30 fps with a shutter speed of 1/60 sec. I suspect that it is this close match in shutter speed (and thus similarity in image sharpness) that creates the impression of viewing a soap opera when we watch Bilbo Baggins and company.

In the future, after years of experiencing HFR movies, will we be able to appreciate the more realistic renderings garnered by this new technology? Will a younger generation without prior associations to videotaped TV programs be enamored by the sharper images? Time will tell, though I’m skeptical. HFR does offer a more realistic rendering than what we’ve previously encountered at the movies, and further advances may help to refine its use. Yet do we really want to have an entirely realistic portrayal? In most cases that would mean having the experience of sitting next to the director watching actors on a sound stage with artificial lighting, which is exactly the impression I had while watching Bilbo backlit by what was supposed to be moonlight. Instead, we may end up preferring a softer image which maintains the illusion of being engaged in an adventure with our favorite fictional characters and partaking in a wonderfully unexpected journey.

Arthur P. Shimamura is Professor of Psychology at the University of California, Berkeley and faculty member of the Helen Wills Neuroscience Institute. He studies the psychological and biological underpinnings of memory and movies. He was awarded a John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship in 2008 to study links between art, mind, and brain. He is co-editor of Aesthetic Science: Connecting Minds, Brains, and Experience (Shimamura & Palmer, ed., OUP, 2012), editor of the forthcoming Psychocinematics: Exploring Cognition at the Movies (ed., OUP, March 2013), and author of the forthcoming book, Experiencing Art: In the Brain of the Beholder (May 2013). Further musings can be found on his blog, http://psychocinematics.blogspot.com.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only television and film articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post HFR and The Hobbit: There and Back Again appeared first on OUPblog.