new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: vcfa, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 25 of 48

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: vcfa in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By

Melanie Fishbanefor

Cynthia Leitich Smith's

CynsationsConfession. I have a difficult time celebrating my success. When it comes to my accomplishments there is a little voice in my head that suggests, as the

Kirsty MacColl song goes, “You Just Haven’t Earned It Yet Baby.”

Perhaps it is also because my path to publication is a bit unconventional. I couldn’t believe it when I was approached by Lynne Missen of Penguin Canada (now Penguin Random House of Canada) with the possibility of writing a YA novel about my favourite author,

L.M. Montgomery.

I hadn’t finished my MFA yet at

Vermont College of Fine Arts, I didn’t have an agent (and still don’t), and was still deep in another book that had a mind of its own.

|

| Melanie delivers her graduate lecture at VCFA |

What had Lynne seen in my writing that made her think I could do this? Sure, I had been lecturing on L.M. Montgomery at conferences, and had wanted to write historical fiction for kids ever since I learned it was a thing you could do…but there had to be other, way more established authors, who could do this better than I.

Lynne asked me to put together a proposal with an outline and a few sample chapters that would demonstrate my vision for the novel. Three months later, I sent a ten-page proposal and the first forty pages and waited. And waited.

After about a month or so (see, didn’t wait all that long!) I was asked to revise those chapters; I suspect to see how well I took editorial feedback. I went home and worked on the revisions, seeking to prove to Lynne that she hadn’t put her faith in the wrong person, and to myself that this was possible. About a month after that I sent her the revisions. And waited.

After about a month or so (see patience is a practice!) I was given an offer. As I didn’t have an agent, and I think too new to understand that I could have found one to help me negotiate the deal, I hired an entertainment lawyer, who helped me navigate all of those non-writerly things that can make us uncomfortable.

Over the next four and a half years I devoted myself to the book.

I also learned how to trust the process and see the editor as a partner who wanted what was best for me and the book. Lynne allowed me to explore characters and scenes that ended up on the proverbial cutting room floor, but also asked the right (sometimes annoying) questions, encouraging me to go deeper, find Maud’s character, as well as craft the world in which she would live.

I kept wondering if I was taking too long writing the book, but Lynne assured me that we wanted it to be the best book it could be. So, I trusted her and kept writing.

When the ARC of

Maud: A Novel Inspired by the Life of L.M. Montgomery, arrived on my doorstep a few months ago, there was a little postcard from Lynne congratulating me. And while I couldn’t quite believe that this was my success, I trusted (again) she knew something I didn’t.

Wrapping it in a plastic bag and then a padded computer case (because it was my only copy) I carried it around with me, showing it to people, and stepping into the idea that this was something to be celebrated. That whatever our path to publication is, honor it, hold it close, and then set it free.

By

Cynthia Leitich Smithfor

CynsationsJenn Bishop is the first-time author of

The Distance To Home (Knopf, 2016). From the promotional copy:

Last summer, Quinnen was the star pitcher of her baseball team, the Panthers. They were headed for the championship, and her loudest supporter at every game was her best friend and older sister, Haley.

This summer, everything is different. Haley’s death, at the end of last summer, has left Quinnen and her parents reeling. Without Haley in the stands, Quinnen doesn’t want to play baseball. It seems like nothing can fill the Haley-sized hole in her world. The one glimmer of happiness comes from the Bandits, the local minor-league baseball team. For the first time, Quinnen and her family are hosting one of the players for the season. Without Haley, Quinnen’s not sure it will be any fun, but soon she befriends a few players. With their help, can she make peace with the past and return to the pitcher’s mound?

Was there one writing workshop or conference that led to an "ah-ha!" moment in your craft? What happened, and how did it help you? After querying two projects and having plenty of full requests but no offers, I felt stuck in that place I'm sure many other writers have found themselves in. You're so close, but still not there yet.

There's something holding you back, but no one has been able to articulate it. And since you're the writer, you don't have the capacity to objectively evaluate your own finished product. Of course the story works for you; you wrote it!

It was at this point in my writer's journey—after feeling frustrated with being so close and still not there yet, that I applied to

Vermont College of Fine Art's MFA program in Writing for Children and Young Adults.

The ah-ha moment for me came during the first residency, and was followed by many ah-ha moments in the subsequent ones.

In workshop, each time we met, two writers had their work critiqued by the group. You might think my ah-ha moment came during my own critique, but as I remember, it came from looking closely at the work of my peers.

Suddenly, it started to click—what all those agents had been trying to tell me, but which I had failed to see. I wasn't letting the reader along on the journey with the character, not entirely.

You see, on the surface there was nothing wrong with my writing. Like so many English lit majors, I knew how to write at the sentence level. But what I didn't know—what I was only just beginning to learn—was how to tell a story. Maybe still that language is not perfectly precise.

What I was failing to do was let the reader in on the journey of the story. I was trapping the reader outside of it; it wasn't a lived, breathed experience for them.

I could see this difference as I read my peers' work. Some of us were still in the same stage as me; perfectly suitable writing, but not a lived experience. And others, with interiority and voice, had allowed the reader to become an active participant in the story.

Later in the program,

Rebecca Stead came as a visiting writer and lectured on this participant quality. She spoke of how writing is providing the 2+2 of the equation, and letting the reader put that together to make four.

Like so many beginning writers, I was always writing out the full equation. Not letting the reader to inhabit the story and do the work.

This revelation was one that shook the big picture. It didn't allow for an easy or quick fix. What it meant was that I had to start all over in my thinking of how to tell a story, what to share with the reader and how.

Like so many things in writing, it was just the beginning.

As a contemporary fiction writer, how did you deal with the pervasiveness of rapidly changing technologies? Did you worry about dating your manuscript? Did you worry about it seeming inauthentic if you didn't address these factors? Why or why not? Coming from a librarian background, I tend to have the long haul in mind. The truth is most books will have longer shelf lives in libraries than they ever will in a bookstore. Who wouldn't want their book to be serendipitously discovered by a teen three, five, ten years after it was published?

As a teen librarian, I assessed the teen fiction collection annually, having to—gulp—discard the books that were no longer circulating to make room for new books.

In truth, some books don't have a long shelf life because they are so technology-obsessed that they date themselves within a few years.

As a middle grade writer, I have it a little easier than YA authors, with technology being not quite as big a part of a ten-year-old's life. That said, there are certain technologies that don't seem to be going away, and it's not in my interest to avoid anything my characters would be using in real life.

In The Distance To Home, text messaging plays a key role in the plot. While I'm a little wary of using branded applications, like Facebook and Twitter, whose purposes and uses have evolved quite a bit in the past five years, it's important at the end of the day to be true to your reader's world.

Anytime you avoid their reality, you risk the chance of a reader feeling jolted out of the story by something that feels inaccurate or false.

|

| This revision kitty always rests on freshly printed manuscripts. |

By

M.T. Andersonfor

Cynthia Leitich Smith's

CynsationsThe Vermont children’s book community had an incredible treat on Oct. 7 at the Stowe Cinema 3Plex in Stowe, Vermont:

We all descended on a movie theater in Stowe where

Katherine Paterson had opted to hold the premiere of the film adaptation of her National Book Award-winning middle-grade masterpiece,

"The Great Gilly Hopkins" from Lionsgate. It was a formal champagne and popcorn kind of event.

(Begging a question: What Would Gilly Do? Somehow I see Mountain Dew hitting the screen during the touching scenes.)

Several generations of Patersons were there, including Katherine’s sons David (who wrote the screenplay) and John (who produced).

It’s a wonderful movie, with a cast that includes

Glenn Close,

Octavia Spencer,

Kathy Bates, and, in a delicious little cameo, Katherine herself. Fans of the book will be delighted to see how much of the original dialogue has been lovingly retained – one of the benefits of having the author’s son as screenwriter.

Afterwards, Katherine admitted that Kathy Bates will now play Maime Trotter permanently in her head, and I think many of us would agree. The way she inhabited that iconic character was flawless and deeply moving.

The screening was followed by a panel with Katherine, David, and John talking about the genesis of both the book and the movie. They reminisced about the two children whose stay with the Paterson family in the late seventies led more or less to Katherine’s conception of the novel – and to her vision of Gilly’s rage at her situation. And they talked about how they’d maneuvered the project through Hollywood, trying to keep the story intact.

At the same time, they spoke frankly about why certain details differed from the book to the movie … the swapping of the case-worker’s gender, for example. (It would be a fun class discussion to have!)

It was a real delight to see the movie and then, immediately, hear these three talk about it. The evening was organized by

Vermont College of the Fine Arts as a benefit for

Tatum’s Totes, a charity which provides emergency bags filled with clothes, blankets, and toys for foster kids in transit.

By the way,, the movie is apparently available for streaming online at all the usual venues (iTunes, Amazon), if it’s not showing at your local theater. Though that service doesn’t come with as many Patersons.

By

Cynthia Leitich Smithfor

Cynsations I'm honored to announce that

Gayleen Rabakukk has been chosen as the summer-fall 2016 Cynsations intern. Thanks to all who applied!

Here's more from Gayleen:

By

Gayleen Rabakukkfor

Cynthia Leitich Smith's

Cynsations“You mean you both just sit there and write? On different things? And don’t talk?”

“Yes,” I tell my non-writing friends.

I realize how odd that may sound. There was a time when I would have thought it was strange, too. For many years, I’d done all my writing alone. I’d published lots of newspaper and magazine articles, exploring topics ranging from exotic pets to forensic science.

Eventually, I felt the pull to make something that would last longer than the weeks a magazine article is around, so I tried my hand at adult mysteries, (one of my favorite genres) and eventually young adult novels.

Looking for help with the transition from journalist to novelist, I became active with the

Oklahoma Writers Federation, Inc. (OWFI), volunteering at their annual conference and serving on the board as a grant writer. After a few rejections, I decided instead of guessing what “narrative voice” and “connecting with the character” meant, I would go back to school and really learn how to write for children and young adults.

|

| Sharon |

I applied to

Vermont College of Fine Arts, doubting that this Oklahoma journalist would be accepted.

When I got a call from

Sharon Darrow one afternoon welcoming me to the program, I couldn’t believe it!

My initial residency was filled with firsts: first time in New England, first time my nostrils froze, and the first time I really had deep, serious conversations about writing.

|

| Rita & Gayleen |

I ended up in a small workshop led by

Tim Wynne-Jones where I learned about objective correlatives and adding layers of meaning to your writing. I learned so much I thought my head would explode.

That feeling continued, to varying degrees, throughout my four semesters. The more I learned, the more I realized I didn’t know.

Each semester I had a new advisor.

Jane Kurtz,

Cynthia Leitich Smith,

Rita Williams-Garcia and

Franny Billingsley taught me how to write, how to read, and how to apply what I learned to my own work.

I squeezed writing and reading children's literature into every spare moment I could find: audio books during my daily commute, writing on lunch breaks and in the evenings, reading on the treadmill. Fortunately, my youngest learned how to cook, otherwise my family might have starved while I was a grad student.

After graduation, I tried to stay on track, but the writing demands of my day job had increased and I didn’t have as much time for children's books.

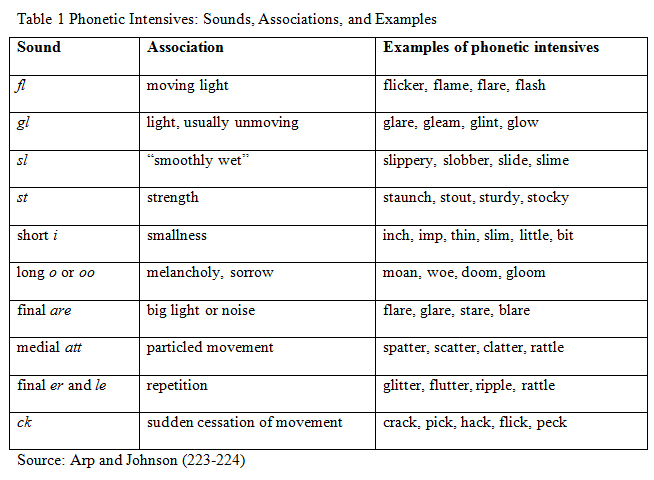

The Supreme Court of Oklahoma wanted me to write a book about the art collection at the Oklahoma Judicial Center. It would definitely be published, and in a format that would be around for a long time. This was what I had set out to do so many years ago: create work that would last longer than a magazine article.

Almost immediately after that project ended, another one came along: the

Oklahoma County Medical Society was looking for a writer to document their history. Once again, it was a book that would definitely be published, with guaranteed monetary compensation.

It wasn’t children's literature, but it would prove that I could generate steady income as a writer (at least during that year-long project.)

I learned so much writing those books: from research techniques to the dynamics of working with a collaborator, yet something was missing. I wanted to recapture that sense of camaraderie I’d felt in Vermont.

Most of my writing efforts up to that time had been solitary. Sure, I had writer friends and occasionally exchanged manuscripts with several of them.

I paid my membership fees to OWFI and

SCBWI, but I had never really embraced the idea of being part of the “writing community.”

After all, I told myself, writing is a solitary pursuit – I’m the one putting words on the page, no one can really help me with that. Vermont was a magical Brigadoon: like-minded writers all gathered on a hilltop for a fortnight. That sort of thing just didn’t happen in the real world.

|

| Meredith & Gayleen |

Then a geographical shift led me to a paradigm shift. Last July, my family and I moved to Austin, Texas and I quit my day job. This put me in close proximity to

Meredith Davis, a fellow VCFA classmate and other alums. The first time she suggested we get together to write, I was a little skeptical, but I gave it a shot. I said “yes” and apparently, that’s all it took for me to realize the benefits of writing in a community.

Now these group writing times take precedent on my weekly calendar. Sometimes it’s just Meredith and me meeting at a coffee shop, other times it’s an organized potluck retreat with half a dozen writers. At the end of the day, it’s still just me putting those words on the page, but I’m learning that spending time with other children's writers provides a creative energy that recharges my batteries and keeps me coming back to the page, day after day – long after I’ve left the coffee shop.

It’s enormously increased my productivity: in the last year, I’ve worked through two complete revisions of a middle grade steampunk manuscript, drafted a new middle grade mystery, started a new historical manuscript and finished a nonfiction picture book.

In an effort to draw others into this awesome community, I recently began co-moderating the middle grade book club for our

SCBWI chapter. Our goal is “reading for writing,” so we analyze and discuss character motivations, plot and point of view in depth. It all takes place on Facebook, which means I get to work it into my schedule wherever it fits, instead of trying to make it to a meeting at a certain time.

There are several book club members I’ve never met in person, but we’re connected through our book discussions, and I continue to grow in both my knowledge and passion for children’s literature.

Some days I’m still trying to figure out how to connect with readers, but I’ve learned a lot about the importance of connecting with a community. Writing discussions aren’t just reserved for snowy hilltops, they can happen in coffee shops, libraries and even on Facebook.

You just have to say "yes."

By

Louise Hawesfor Cynthia Leitich Smith's

CynsationsFrom the promotional copy of

The Language of Stars by

Louise Hawes (McElderry, 2016):

Sarah is forced to take a summer poetry class as penance for trashing the home of a famous poet in this fresh novel about finding your own voice.

Sarah’s had her happy ending: she’s at the party of the year with the most popular boy in school. But when that boy turns out to be a troublemaker who decided to throw a party at a cottage museum dedicated to renowned poet Rufus Baylor, everything changes. By the end of the party, the whole cottage is trashed—curtains up in flames, walls damaged, mementos smashed—and when the partygoers are caught, they’re all sentenced to take a summer class studying Rufus Baylor’s poetry…with Baylor as their teacher.

For Sarah, Baylor is a revelation. Unlike her mother, who is obsessed with keeping up appearances, and her estranged father, for whom she can’t do anything right, Rufus Baylor listens to what she has to say, and appreciates her ear for language. Through his classes, Sarah starts to see her relationships and the world in a new light—and finds that maybe her happy ending is really only part of a much more interesting beginning.

The Language of Stars is a gorgeous celebration of poetry, language, and love. What was your initial inspiration for The Language of Stars?In 2008, I stumbled on a newspaper article about a group of Vermont teenagers who'd been caught throwing a party in the historically preserved summer home of

Robert Frost. They'd vandalized and set fire to the place, but few of them were over eighteen.

A resourceful judge, who couldn't send them to jail, sentenced them to something some of them may have enjoyed even less—they had to take a course in Frost's poetry!

As soon as I read this, my writer's "what-if" machinery kicked in: what if, I asked myself, the poet in question weren't Robert Frost, but an equally famous, Pulitzer-prize winning, world-renowned Southern poet, someone who made his home in North Carolina, where I live? What if, unlike Frost, who'd been dead for decades when the vandalism happened, my fictional southern bard was still alive when young party-goers destroyed his house? And what if he decided to teach those kids himself? What if one of those students was a young girl who showed a natural ear for poetry?

What was the timeline between spark and publication, and what were the major events along the way?It was a

long gestation period! First, I needed to find my narrator, who turned out to be sixteen-year old Sarah Wheeler, a character who came to me almost immediately, but whose voice and interior life took me months of free writing to uncover.

Next, I read all the biographies on Robert Frost and everything he ever wrote (including some pretty awful plays modeled on seventeenth-century court masques!). After that, free writes helped me hear the voice of Rufus Baylor, my book's poet, who shares some life experiences, artistic convictions, and teaching approaches with Frost, but whose personality and poems are all his own.

Next, it was time to write a draft, submit it to my agent,

Ginger Knowlton at Curtis Brown Ltd. in New York, and then tighten and re-think major aspects of the book. (No, great agents don't line edit; but yes, they do ask crucial questions about readership and story!)

When it was time to submit, I found out the hard way that a YA novel in which an octogenarian is a major character is not an easy sell! I also learned to treasure the judgement and eye of the brilliant editor (Karen Wojtoyla at Margaret McElderry) who trusted my book enough to acquire it and to ask me to rewrite it. Again?!

Grand total?

Seven years from inspiration to completion! Which may be why, in comparison, the year between signing and publication seems to have flown by!

What were the major challenges (research, craft, emotional, logistical) in bringing the book to life? |

| Sarah Bernhardt's Hamlet |

You've named the usual suspects, Cyn. Research and craft, as well as sustaining emotional and artistic investment through so many years, most of them without a contract—all of it was far from easy. But the thing I found most difficult and at the same time most rewarding, was combining the three formats I wanted the novel to include.

First, Stars is written mostly in prose; it's not a novel in verse. Second, of course, it also features poetry. I mean, hello? Most of the major characters in the book have chosen to study poetry rather than do hard time!

Lastly, because my narrator, Sarah, is a wannabe actress whose role model is

Sarah Bernhardt, and because she and her mentor, Rufus, hear the whole world talk, talk, talking to them, I've also included play scripts that feature an on-going dialogue between things and people.

In the vibrant and highly auditory place Rufus and Sarah inhabit, grills sputter, furniture squeaks, sand crabs burrow, seagulls squeal—not just as background noise, but as active, contributing participants. Fun? Yes. But challenging to write!

Talk to us about your audition to read the audio edition of the book for Brookstone.I have a theater background, so I asked my agent to write an author audition into the audio contract for Stars. After all, I reasoned, I had been a national finalist in the

National Academy of Dramatic Arts competition; I had endured NYC audition rounds, portfolio in hand; and colleagues and students at the

Vermont College of Fine Arts had listened attentively to my readings from each draft of Stars. Who was better suited to bring the audio book to life?

A lot of people, it turns out! Blackstone Audio required a short five-minute sample—a cinch, right? It took me days to come up with that recording, but it took the company's studio director exactly three hours to respond to my emailed mp3.

What he told me, kindly but firmly, was that audio listeners have well-developed tastes and high expectations, the least of which is that a teenage narrator's voice will sound as if she's between the ages of 14 and 20. To soften the blow, and because I did have prior recording experience, he asked if I would help him select our reader from among their final candidates.

Here's the humble pie part: the part where I tell you that any one of their top ten voice actors were about 900 billion times better qualified to read my book than I was!! Yes, I got to make the final call:

Katie Schorr is a full-time actor, an all-round stage talent, and gives one of the most nuanced, sensitive readings I've ever listened to on audio. I can hardly wait for everyone to hear it!

What's new and next in your writing life?A lot! Current works in progress include The Gospel of Salomé, YA historical fiction about the young woman the new testament credits with having danced off the head of John the Baptist; Love's Labor, an adult novel about an aging playwright; and Big Rig, a brand new middle-grade novel.

In addition to working on my own projects, I'm also cooking up another

Four Sisters Playshop with my three sisters—a painter, a musician, and a film-maker. We'll be exploring a new theme in August 2017: Death, Cradle of Creativity. We hope to share writing, movement, music, sculpture and painting with participants, and in the process destroy a lot of stereotypes about death and aging!

By

Skila Brownfor

Cynthia Leitich Smith's

CynsationsSkila Brown is the author of verse novels Caminar and To Stay Alive, as well as the picture book Slickety Quick: Poems About Sharks, all with Candlewick Press. She received an M.F.A. from Vermont College of Fine Arts. She grew up in Kentucky and Tennessee and now lives in Indiana where she writes books for readers of all ages.We all reach a point when writing doesn’t feel very fun. Maybe because we’ve read too many rejection letters. Or maybe because we’ve revised so much we can’t recognize our story. Or maybe because we’re under a deadline and the pressure to finish takes away all the enjoyment.

|

| October, 2016 |

But remember why we started doing this? It wasn’t because we wanted to get rich quick. (Ha!) Or because it was the only job we could do. Or because anyone was making us write. It was because it was fun.

The art of creating story was fun. We became writers because we like telling stories—we like making up details, researching history and narrating events. All of that was fun.

Six years ago, I got serious about becoming a writer and applied to an MFA program. When I got a call from the admissions office saying, “Hey – we’re doing this intensive picture book semester and we have room for one more student. Would you like to try it?”

I thought, That could be fun. And I soon found myself immersed.

Six months of reading almost nothing but picture books. Dozens of picture books. Hundreds of picture books. Rhyming ones, silly ones, concept books, fairy tales. Biographies, bedtime stories, wordless books and—poetry.

The thing about sitting down at the library and reading through a knee-high stack of poetry books is that after reading a dozen, two dozen, I started to see really fast what makes a certain one good. I really liked the ones that were centered around a theme, with varied types of poetry and bonus little nonfiction facts sprinkled on top.

I should try to do that, I thought. Being enrolled in a class that expected me to produce many picture book drafts in a short period of time didn’t let me dwell on whether it was a good idea or not. It just demanded that I try it out. That I play with it.

And I did. It was fun to research shark breeds and learn about sharks I’d never heard of before. (Hello, cookie-cutter shark!)

I spent a lot of time on YouTube watching sharks swim and thinking about their rhythm and shape and how that would feed into a poem. It was fun to learn new stuff. And it was really fun to try my hand at writing all different types of poems.

To challenge myself to make sure the next one didn’t rhyme or the next one was a concrete poem or the next one was a haiku. Not all of the experimenting worked. But every bit of it was fun.

As writers we need to remember what drew us to this field to begin with and do whatever we can to find the fun again. Here are 4 quick ways you can find the fun in writing this week:

- Be a spy. Go outside and find an animal or a plant and just sit and watch it for 10 minutes, writing down whatever comes to mind. See if you can take that and shape it into a poem when the time is up.

- Play a game. Find a Mad Libs. Caption a funny photo.

- Have fun with first lines. Opening sentences can be really fun to make up. Write a list of ten of them and then send the list out to your critique group. Let them vote on one that you’ll turn into a short story.

- Write something that is completely out of your comfort zone. If you normally write YA contemporary, try writing a scene of a middle grade historical novel. Write the end of a story. Write in second person. Do something new and fresh that shakes it up a little in your routine.

It’s worth it to take a break from the WIP and play a little. Remembering what’s fun about writing will improve your energy level on your current project.

But that’s not why you should do it. You should do it because it’s

fun.

Cynsational NotesSkila's new book,

Slickety Quick: Poems About Sharks, was illustrated by Bob Kolar (Candlewick, 2016). From the promotional copy:

Fourteen shark species, from the utterly terrifying to the surprisingly docile, glide through the pages of this vibrantly illustrated, poetic picture book.These concrete poems about a selection of sharks will tickle the fins of many an aspiring marine biologist. —Booklist

All in all, it’s a book that ought to leave many readers fascinated—and perhaps a little unsettled—by the diversity of sharks that exist beneath the waves. —

Publishers Weekly

By Cynsations Readers

By Cynsations Readers

for Cynthia Leitich Smith's Cynsations

Over the past couple of weeks, children's-yA author Cynthia Leitich Smith put out a call for questions from readers on Cynsations and Twitter. Here are those she elected to tackle and her responses. A few questions were condensed for space and/or clarity.

See also a previous Cynsations reader-interview post from November 2010. Cyn Note: It's interesting how the question topics shifted, both with my career growth and changes in publishing. Back then, readers were most interested in the future of the picture book market and online author marketing.

Craft

What’s the one piece of advice you think would most benefit children’s-YA writers?

Read model books across age levels, genres, and formats. For example, a novelist who studies picture books will benefit in terms of innovation, economy and lyricism of language.

Writing across formats has its benefits, too. No, you won't be as narrowly branded. But you will have more options within age-defined markets that rise and fall with birth rates. You will acquire transferable skills, and, incidentally, you'll be a more marketable public speaker and writing teacher.

Are you in a critique group? Do you think they’re important?

Not right now, but I have been in the past.

These days, I carry a full formal teaching load. Each year I also tend to lead one additional manuscript-driven workshop and offer critiques at a couple of conferences. That leaves no time for regular group meetings or the preparation that goes into them—my loss.

For me, participation offered insights (by receiving

and giving feedback) as well as mutual support related both to craft and career.

From a more global perspective, considerations include: whether the group is hard-working, social or both; the range of experience and expertise; the compatibility of productivity levels; and the personality mix.

The right combination of those ingredients can enhance the writing life and fuel success. A wrong one can be a serious detriment. If you need to make a change, do it with kindness. But do it.

What can an MFA in writing for kids do for me?First, my perspective is rooted in my experience as a faculty member in the low-residency

Writing for Children and Young Adults program at Vermont College of Fine Arts.

|

| With Kathi at the Illumine Gala |

You don’t

need an MFA to write well or to successfully publish books for young readers.

I don’t have an MFA. My education includes a bachelor’s in

journalism from the University of Kansas and a

J.D. from The University of Michigan Law School. I also studied law abroad one summer in Paris.

Beyond that, I improved my children’s writing at various independent workshops, most notably those led by

Kathi Appelt in Texas.

That said, you will likely develop your craft more quickly and acquire a wider range of knowledge and transferable skills through formal study.

My own writing has benefited by working side-by-side with distinguished author-teachers. Only this week, I heard

Tim Wynne-Jones’s voice in my mind—the echo of a lecture that lit the way.

You’ll want to research which program is best suited to your needs.

Your questions may include:

|

| Gali-leo |

- Do you want a full- or low-residency experience?

- What will be the tuition and travel/lodging costs?

- What financial aid is available?

- Are you an author-illustrator? (If so, Hollins may be a fit.)

- Are you looking for a well-established program or an intimate start-up?

- What is the faculty publication history?

- How extensive is the faculty's teaching experience?

- How diverse is the faculty and student body?

- How impressive is the alumni publication record?

- How many alumni go on to teach?

- How cohesive--active and supportive--is the alumni community?

Talk to students and alumni about the school’s culture, faculty-student relationships, creature comforts and hidden expenses.

Across the board, for children's-YA MFA programs, the most substantial negative factor is cost.

CareerIn terms of marketing, what's one thing authors could do better?Provide the name of your publisher and, if applicable, the book's illustrator in all of your promotional materials, online and off. If you're published by, say, Lee & Low or FSG, that carries with it a certain reputation and credibility. Also, readers will know which publisher website to seek for more information and which marketing department to contact to request you for a sponsored event.

Granted, picture book authors usually post cover art, which includes their illustrators' names. But we're talking about the books'

co-creators, and they bring their own reader base with them. Include their bylines with yours and the synopsis of the book whenever possible. It's respectful, appreciative and smart business.

What’s new with your writing?I’ve sold two poems this year, one of which I wrote when I was 11. How cool is that?

I'm also working steadily on a massive update and relaunch of my official author site, hopefully to go live for the back-to-school season.

What are you working on now?

I’m writing a contemporary realistic, upper young adult novel. It’s due out from Candlewick in fall 2017.

Like my tween debut,

Rain Is Not My Indian Name (HarperCollins, 2001), the upcoming book features a Muscogee (Creek)/Native American girl protagonist, is set in Kansas and Oklahoma, and is loosely inspired by my own adolescence.

Meanwhile, if you’d like to take a look at my recent contemporary realism, check out the chapter “All’s Well” from

Violent Ends, edited by

Shaun David Hutchinson (Simon Pulse, 2015).

What’s next for your Tantalize-Feral books?For those unfamiliar with them, the

Tantalize series and

Feral trilogy are set in the same universe and share characters, settings and mythologies. These upper YA books are genre benders, blending adventure, fantasy, the paranormal, science fiction, mystery, suspense, romance and humor.

Feral Pride, the cap to the Feral trilogy, was released last spring. It unites characters from all nine books, including Tantalize protagonists.

A new short story set in the universe, “Cupid’s Beaux,” appears in

Things I’ll Never Say: Stories About Our Secret Selves, edited by

Ann Angel (Candlewick, 2015).

I don't have immediate plans for more stories in the universe, but it's vast and multi-layered. While I'm focusing on realistic fiction now, I'll return to speculative in the future.

DiversityHow do I make sure that no one will go public with a problem about my diverse book? First, you can't (and neither can I).

Second, this has become a too-popular question.

To fully depict today's diverse world,

we all have to stretch--those who don't with regard to protagonists will still be writing secondary characters different from themselves.

Writers of color, Native writers and those who identify along economic-ability-size-health-cultural-orientation spectra are not exempt from the responsibilities that come with that.

I'm hearing a

lot of anxiety from a

lot folks concerned about being criticized or minimized for writing across identity elements. I'm also hearing

a lot of anxiety from

a lot of folks concerned with "getting it right."

For the health of my head space, the latter is the way to go. My philosophy: Focus on doing your homework and offering your most thoughtful, respectful writing.

Focus on advocating for quality children's-YA literature about a wide variety characters (and their metaphorical stand-ins) by a wide range of talented storytellers.

I make every effort to assume the best.

By that, I mean:

- Assume that when people in power say that they're committed to a more diverse industry and body of literature, they mean it and will act accordingly.

- Assume they'll eventually overcome those who resist.

- Assume that your colleagues writing or illustrating outside their immediate familiarity connect with their character(s) on other meaningful levels.

- Assume that you'll have to keep stretching and connecting, too.

- Assume that #ownvoices offer important insights inherent in their lived experiences.

- Assume that being exposed to identity elements and literary traditions outside your own is a opportunity for personal growth.

- Assume that a wider array of representations will invite in and nurture more young readers.

- Assume that your voice and vision can make a difference, not only as a writer but signal booster, advocate and ambassador.

If only in the short term, you risk being proven wrong. You risk being disappointed. At times, you probably will be. I've experienced both, but I'd rather go through all that again than to try to effect positive change in an industry, in a community, I don't believe in.

I've been a member of the children's-YA writing community for 18 years. Experience has taught me that I'm happier and more productive when I err on the side of optimism, hope and faith.

Do you think that agents are reluctant to sign POC writing about POC after Scholastic pulling A Birthday Cake for George Washington? No need to panic. As the diversity conversation has gained renewed momentum, many agents have publicly invited queries from POC as well as Native, disabled, LGBTQIA writers and others from underrepresented communities. For example,

Lee Wind at I’m Here. I’m Queer. What the Hell Do I Read? is hosting an interview series with agents on that very theme.

I can't promise that every children's-YA literary agent prioritizes or, in their heart of hearts, considers themselves fully open to your query. But those who don't aren't a fit for you anyway.

When you’re identifying agents to query, consider whether they have indicated an openness to diverse submissions and/or take a look at who’s on their client rosters. This shouldn't be the only factor of course, but one of many that you weigh.

On your blog, you feature a lot of trendy type books (gay) we didn’t have in the past.Not a question, but let’s go for it. If I’m deciphering you as intended, I disagree with the premise. Books with gay characters aren’t merely a trend or, for that matter, new in YA literature.

Nancy Garden’s

Annie on my Mind was published in 1982.

Marion Dane Bauer’s anthology

Am I Blue? Coming Out from the Silence was published in 1994.

Brent Hartinger’s

Geography Club was published in 2003. One place to find recent ALA recommendations is the

2016 ALA Rainbow Book List.

Cynsations coverage is inclusive of books with LGBTQIA characters. In addition, gay and lesbian secondary characters appear in my own writing.

The blog was launched in 2004. Over time, I've noticed fluctuations in social media whenever I post LGBTQIA related content. I lose some followers and gain others. Increasingly, I lose fewer and gain more. My most enthusiastic welcome to those new followers!

(Incidentally, I used to see the same thing with regard to books/posts about authors and titles featuring interracial families or multi-racial characters.)

More Personally You sometimes tweet about TV shows. What do you watch?In typical geeky fashion:

“Agent Carter;” "Agents of Shield," “Arrow;” “Bones;” “Castle;” “The Flash;” “Grimm;” “iZombie;” “Legends of Tomorrow;” "The Librarians;" “Lucifer;” “Once Upon a Time;” “Supernatural.” |

| Created by Rob Thomas, who has also written several YA novels. |

Comedy-wise:

“Awkward;” “The Big Bang Theory;” “Blackish;” “Crazy Ex-girlfriend” (I'm a sucker for a musical);

“Fresh off the Boat;” “The Real O’Neals;” “Superstore.”I’m trying

“Community” and still reeling from the

"Sleepy Hollow" finale.

I have mixed feelings about

“Scream Queens,” but I’m fan of

Jamie Lee Curtis and

Lea Michele, so I’ll keep watching it. Ditto “Big Bang” with regard to

Mayim Bialik and

Melissa Rauch.

"Lucifer" sneaked up on me. As someone

who's written Lucifer, I watched it out of curiosity as to the take. I keep watching it because it surprises me and because

Scarlett Estevez is adorable.

Typically, I watch television while lifting weights or using my stair-climber. I love my climber. I do morning email on it, too. It's largely replaced my treadmill desk.

While I write, I use the television to play YouTube videos, usually featuring aquariums, blooming flowers, butterflies or space nebulas, all set to soothing music.

Trivia: Probably I’ve logged the most small-screen time with

David Boreanaz due to

“Buffy: The Vampire Slayer,” “Angel,” and

“Bones.” I know nothing about the actor beyond his performances (I’m not a “celebrity news” person), but I like to think he appreciates my loyalty.

Cynsational GiveawaysEnter to win signed books by Cynthia Leitich Smith -- the young adult Feral trilogy (Candlewick) and/or three Native American children's titles (HarperCollins). Scroll to two entry forms, one for each set.

a Rafflecopter giveawaya Rafflecopter giveaway

By

Cynthia Leitich Smithfor

CynsationsWelcome, Alan Cumyn! What was your initial inspiration for Hot Pterodactyl Boyfriend (Atheneum, 2016)?There’s a short answer and a long one. The short: in January 2012, popular YA author

Libba Bray gave a speech to over a hundred writers at

Vermont College of Fine Arts in which she brought us through the ups and downs of her writing career.

Three times in the course of an hour she said, “Don’t go writing your hot pterodactyl boyfriend novel.” She meant that we shouldn’t slavishly follow the trends. But I was struck by the phrase.

When I approached her afterwards and said that I was getting an idea, she encouraged me to follow up, and a little later the whole first chapter, in which the pterodactyl, Pyke, arrives at Vista View High in a calamitous fashion – by landing unceremoniously on the cross-country running champion, Jocelyne Legault – more or less fell out on the page for me.

The longer answer takes me back more than ten years when I was riding a train from Toronto to Ottawa. I had been at some publishing event or other, and was full of the possibility of new stories.

The train rounded a bend and Lake Ontario came into sight. On a rock by the shore a great blue heron, which looked like an ancient creature, pierced me with his gaze. It was the oddest feeling – I felt locked in direct communication with an intelligence not only from another species, but from a vastly different time.

Seconds later the landscape changed, the heron was gone, but I pulled out my pad and scribbled furiously for several pages about a heron who is able to change into a man at will, and who wanders into the big city from time to time almost as a vacation from his usual existence.

After a time I stopped writing because I realized I didn’t know enough about herons to proceed. Over the years, I worked on several versions of this story, and got sidetracked with an interest in

Kafka, whose "The Metamorphosis" (1915) famously envisioned a man who wakes up one morning transformed into a bug. I was drawn to the idea of introducing something startlingly unreal and fantastical, but continuing the rest of the story in as realistic a fashion as possible. I was also, like so many others, attracted by the dreamlike nature of Kafka’s writing.

The story morphed and became at least two entirely different novel-length manuscripts that sputtered for various reasons and never quite worked. And then: “Don’t go writing your hot pterodactyl boyfriend novel.” I was seized with yet another possibility to work with some of the same ideas and influences, and perhaps not take it so seriously this time.

What was the timeline from spark to publication, and what were the major events along the way? |

| U.S. cover art |

That first chapter poured out of me within a day or two of hearing Libba Bray speak in January 2012. I sent a full draft to my agent,

Ellen Levine, in late December 2013, so it took me about two years to write much of the manuscript.

During most of that time I told nobody what I was working on. I like the freedom to go wherever I want on the page and to fail privately in ridiculous ways if need be.

After that strong opening chapter fell out, I slowly went over that material again and again for clues about how the story must proceed with these characters in the situation they find themselves in.

Before showing the draft to Ellen, of course, I got feedback from my wife Suzanne, and from friends and family, and made it as strong as I could.

Ellen contacted me enthusiastically in February 2014 and I worked on some more revisions for her. She sent it out to publishers in March and, although a lot of editors passed on it, we did get offers in April, with

Caitlyn Dlouhy at Atheneum winning out.

I was way up north in Dawson City, Yukon Territory, Canada at the time as writer-in-residence at Berton House when the phone line to New York started to burn up. It was exciting and strange, to be so far away and yet to have such interest suddenly welling up about my unusual pterodactyl novel. (Hot Pterodactyl Boyfriend, it turns out, is the first novel of mine to be published simultaneously in Canada, the United States, the U.K. and elsewhere.)

|

| U.K. cover art |

I got a chance to meet Caitlyn in New York in July 2014, and U.K. editors in September. When I was in New York I also spent time at the Museum of Natural History which just happened to be showing a major exhibit on pterodactyls!

Some of the latest research changed the way I thought about the physicality of Pyke, and made it into the book. A lot of the revisions for Caitlyn involved strengthening middle parts of the story and ending it in a way that stayed true to the characters, and to the strangeness of the whole telling.

Again – I kept going back to the beginning for inspiration. The manuscript was pretty well finalized by April 2015, and I was reviewing galleys in October.

There wasn’t a major crisis or anything, no pitched battles, but Caitlyn and I did have strong discussions about all the characters and themes.

I take it for granted that my creations will feel real to me, but it’s lovely when an editor so fully immerses herself as well.

What were the challenges (literary, research, emotional, logistical) in bringing the story to life?Nothing about this story was straightforward. On the opening page, Pyke appears as a speck in the sky, and by the end of that chapter he is the first inter-species transfer student in the history of Vista View High.

The initial challenge – how do the students accept him as anything but a monster come to eat the school? – I skirted in my first draft by summarizing the changes in a paragraph or two. It was only fairly late in revision that I realized I needed to show in scene those crucial minutes after Pyke has landed on Jocelyne and then carried her to the school nurse for attention.

Pyke is not the main character, of course – the story actually belongs to the student body chair, Shiels Krane, an A-type leader whose well-ordered plans for her graduation year have nothing to do with dealing with a pterodactyl who steals everyone’s heart, including her own.

In that way I was able to shift the question about believability – if Shiels buys into it, then it’s easier for the reader to believe, too. I did do a lot of background reading on pterodactyls, but in my mind I was treating Pyke as the ultimate bad-boy boyfriend, and that’s part of the fun of the story, watching characters adapt to a ridiculous situation that turns normal and then actually seems familiar.

We do it all the time in real life, just not with pterodactyls! So often writing fiction convincingly is a matter of taking care of the tiny details, making those seem lifelike, so that the huge lies one tells hardly stand out at all.

What made you commit to the writing life? What did you sacrifice for it?I was very lucky to attend a graduate writing program when I was young, only 24, at the

University of Windsor, where my mentor, Alistair MacLeod, happened to be a brilliant writer and terrific teacher. Without that early formation, I’m not sure I would’ve stuck with it, given all the difficulties I had initially in publishing anything at all.

It took me seven years of strong effort after graduation to get a single short story accepted in a literary journal (for which I was paid $50). My first three novel manuscripts were rejected before the fourth was accepted, and even that one sat in the publisher’s office for over a year before I got a yes.

Along the way I decided I was not going to be the sort of writer who lives in a tiny room in the YMCA, turning his back on life so that he might have time to write. I have worked at a number of full-time jobs that, fortunately, also fed my sense of life and society, and so nurtured my writing as well.

But if I hadn’t married and had children, I doubt I would have written for younger audiences. I faced a really tough decision at around age 40 when the excellent government job I had (as a writer and researcher on international human rights for the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada) seemed to be too much to handle on top of novel writing as well.

Some of my adult novels were suddenly doing well, and I had to make a choice. It was a big gulp – our children were young, Suzanne had just started a doctorate program, and there was no extra money in case things went badly. So with family support I sacrificed the security of a regular paycheck, but was fortunate enough to have waited until my art was strong enough to withstand the pressures of such a decision.

It was the right thing to do, and I haven’t really looked back, especially since part-time teaching at the Vermont College of Fine Arts allows me to use my skills, and helps keep the wolf from the door during the inevitable down times in a writing and publishing life.

What about the business of publishing do you wish you could change?I would love it if editors were not so extraordinarily busy, if they could somehow always keep a sense of the leisure of reading while opening up a new manuscript.

Editors often have crushing workloads and it means “quiet” stories often don’t have a chance to get their attention, they’ve got too many submissions to wade through before going back to their email backlog etc.

I know, it’ll never happen, and the really good editors do find ways to let themselves fall into a story when they read, no matter what their to-do list looks like. But I do think a lot of fine writing is overlooked because of the craziness of today’s schedules.

Cynsational NotesAlan is the faculty chair of the

MFA program in Writing for Children and Young Adults at Vermont College of Fine Arts. See also

Video Interview with Alan Cumyn from Indigo Teeen.

By

Cynthia Leitich Smithfor

CynsationsCheck out the cover for

The Alarming Career of Sir Richard Blackstone by

Lisa Doan (Sky Pony, 2017). From the promotional copy:

A funny middle grade mystery adventure complete with an unconventional knight, a science experiment gone awry, a giant spider, and a boy to save the day!

Twelve-year-old Henry Hewitt has been living by his wits on the streets of London, dodging his parents, who are determined to sell him as an apprentice. Searching for a way out of the city, Henry lands a position in Hampshire as an assistant to Sir Richard Blackstone, an aristocratic scientist who performs unorthodox experiments in his country manor. The manor house is comfortable, and the cook is delighted to feed Henry as much as he can eat. Sir Richard is also kind, and Henry knows he has finally found a place where he belongs.

But everything changes when one of Sir Richard’s experiments accidentally transforms a normal-sized tarantula into a colossal beast that escapes and roams the neighborhood. After a man goes missing and Sir Richard is accused of witchcraft, it is left to young Henry to find an antidote for the oversize arachnid. Things are not as they seem, and in saving Sir Richard from the gallows, Henry also unravels a mystery about his own identity.Congratulations on your upcoming release! What do you think of your new cover?I love it! Huge thanks to Sky Pony and my editor, Adrienne Szpyrka, for capturing the humor of the book while at the same time working in two prominent elements – the giant tarantula and a journal detailing a trip to South America.

The tarantula is Henry Hewitt’s problem and the journal is the key to figuring out what to do about it, which he must do to save his friend and protector, Sir Richard Blackstone.

More specifically, how does the art evoke the nuances of your book?We wanted the journal to feel Old World, hence the faded brown, as this story takes place in the late 1700’s English countryside.

Sky Pony’s designers had the genius idea of having the tarantula holding the journal to tie it all together. The red and yellow lettering really pop and signal the lighthearted tone.

I couldn’t be happier with how it turned out.

Isn’t it every middle-grade writer’s dream to have a cover with a tarantula on it?

I know it has always been one of mine!

Cynsational NotesLisa Doan has an

MFA in Writing for Children and Young Adults from Vermont College of Fine Arts and is the author of the award-winning series

The Berenson Schemes (Lerner).

Operating under the idea that life is short, her occupations have included: master scuba diving instructor; New York City headhunter; owner-chef of a restaurant in the Caribbean; television show set medic; and deputy

prothonotary of a county court. She currently works in social services and lives in West Chester, Pennsylvania.

By: Vicky L. Lorencen,

on 3/31/2015

Blog:

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Critique Group,

Kathi Appelt,

VCFA,

Vermont College of Fine Arts,

Writing career,

Writing Techniques,

Dana Walrath,

Distraction/Procrastination,

David McGinnis,

Joy Peskin,

Add a tag

Vermont College of Fine Arts

Photo by Vicky Lorencen

Kathi Appelt, David Macinnis Gill, Dana Walrath, Joy Peskin

Photo by Vicky Lorencen

You roll your quarters, register, and highlight the dates on the calendar. You pre-pick your plane seat and pack your bags. You’re going to a workshop! You look forward to it for months, fret about how many pairs of shoes to take, and finally, it’s time to blast off. I got to do just that earlier this month when I attended the amazing 12th Annual Novel Writing Retreat at Vermont College of Fine Arts. (If you’d like a great recap of the experience itself, I highly recommend visiting Debbi Michiko Florence’s site.)

I don’t know about you, but time passes at a sloth’s pace leading up to an event, but then the workshop itself whisks by at road runner speed. If you’re not careful (and by you’re, of course, I mean, I’m), it’s easy as gliding up an escalator to let the whole experience slip away once you’re back home.

Watch out for these post-workshop mistakes . . .

1. Rushing to query or submit your manuscript. Some writers think, if I don’t send that editor or agent my manuscript as soon as I get home, they’ll forget all about me. Not true, especially when you wisely offer a little reminder in the first sentence of your cover letter about how you met. Even if a presenter gives you a teensy window–like six weeks–to submit, take your time. Better to email a glistening, well-groomed manuscript, than to rush yourself and offer a schloppy copy. Your work is a reflection of you. Go for shiny, not speedy.

2. Neglecting your notes–if your notes are handwritten (mine always are), type them up. Seriously. It won’t take long, and while you’re typing, you’ll be reviewing the gems the presenters shared with you. It’ll be easy to highlight the parts that resonate with you too. [Next, pop some brackets around a hint or suggestion that perfectly applies to your WIP and cut/paste it into your ms. to serve as a reminder when you return to that section.] Don’t want to type? Use an old school highlighter or sticky notes to spotlight the bits you most want to recall. Put those pages (or copies of them) in the folder of goodies (research, hard copies, feedback) you’re compiling for this new novel. The idea is to incorporate every epiphany, aha and eureka into what you’re working on now, plus you’ll make them easier to find for future follies, that is to say, novels.

Photo by Vicky Lorencen

3. Disconnecting with the people who “clicked” with you. Friend them on Facebook, send a follow-up email or connect with them on LinkedIn. Send a text, a tweet or smoke signal, whatever works for you. These are your new peeps who share your passion. Passing on this chance to expand your circle is criminal, okay, well, at the very least, a pity.

4. Cooling off—you arrived home pooped, but positively giddy about a new idea for your WIP, but then your fervor fizzled. Family, your tyrannical to do list and Facebook eclipsed your euphoria. Don’t let them! If you have a critique group (or a beloved writing buddy), share what you learned with them. Talking about the lectures will help to solidify concepts in your mind. Your group/buddy may also be able to help decide out how to best use what you learned (and of course, you can return the favor). Ask someone to hold you accountable and offer to do likewise.

How about you? How do you keep the momentum moving after a workshop or retreat?

It is our choices, that show what we truly are, far more than our abilities. ~ J.K. Rowling

By:

Bruce Black,

on 6/30/2014

Blog:

wordswimmer

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

VCFA,

Marion Dane Bauer,

Norma Fox Mazer,

ann angel,

my writing process blog tour,

Sharon Darrow,

writing process,

michelle edwards,

Jacqueline Woodson,

Graham Salisbury,

Add a tag

One

of my favorite writers and illustrators, Michelle Edwards, was kind

enough to invite me to join the My Writing Process Blog Tour. Michelle has

written and illustrated numerous books for children, including the National Jewish Book Award

winner, Chicken Man. If you enjoy knitting, you might like to pick up her book on knitting for adults, A

Knitter's Home Companion, an illustrated collection

I want to thank all my fellow Dystropians for submitting their awesome blog posts this month! Each post shared great insight, sparked fun conversations, and contributed to the general awesomeness of the kidlit writing community!

I want to thank all my fellow Dystropians for submitting their awesome blog posts this month! Each post shared great insight, sparked fun conversations, and contributed to the general awesomeness of the kidlit writing community!

To all my readers, please spend some time with this group’s brilliant blogs, witty twitter sites, and buy their books when they come out!

Thank you to:

Jen Baliey

Jessica Denhart

Melanie Fishbane

Peter Langella

Rachel Lieberman

Sheryl Scarborough

Jeff Schill

Here’s all the Dystropians at our graduate semester VCFA residency!

I want to thank all my fellow Dystropians for submitting their awesome blog posts this month! Each post shared great insight, sparked fun conversations, and contributed to the general awesomeness of the kidlit writing community!

I want to thank all my fellow Dystropians for submitting their awesome blog posts this month! Each post shared great insight, sparked fun conversations, and contributed to the general awesomeness of the kidlit writing community!

To all my readers, please spend some time with this group’s brilliant blogs, witty twitter sites, and buy their books when they come out!

Thank you to:

Jen Baliey

Jessica Denhart

Melanie Fishbane

Peter Langella

Rachel Lieberman

Sheryl Scarborough

Jeff Schill

Here’s all the Dystropians at our graduate semester VCFA residency!

By: Ingrid Sundberg,

on 4/4/2013

Blog:

Ingrid's Notes

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

YA,

Young Adult,

Writing Craft,

Writing for Teens,

VCFA,

Writing YA,

March Dystropian Madness,

crafting authenticity,

Crafting Teen Characters,

The Teenage Brain,

Add a tag

Making Peace with the Adolescent Pre-Frontal Cortex: Crafting Teen Characters with Respect and Authenticity

Part 2: Teen Traits (5 through 8)

By Jessica Denhart

In the part one of this article I talked about the teenage brain and the common teen traits of spotty memory, poor impulse control, the desire to do new things, and spending less time with family and more time with friends. Today we’ll talk about the last four traits that will help you craft authentic young adult characters.

In the part one of this article I talked about the teenage brain and the common teen traits of spotty memory, poor impulse control, the desire to do new things, and spending less time with family and more time with friends. Today we’ll talk about the last four traits that will help you craft authentic young adult characters.

5. Heightened Emotions

The one thing that is working completely in the teen brain is the limbic system, which deals with emotion, and is the part of the brain responsible for “pleasure seeking”. This seems to explain a lot about all of the heightened emotions that we deal with in our teen years. I remember feeling as though the entire world was ending when I had a fight with friends, or didn’t get asked out by the boy I liked.

6. Weighting risk and reward differently than adults.

Journalist David Dobbs points out that “Teens take more risks not because they don’t understand the dangers, but because they weigh risk versus reward differently. In situations where risk can get them something they want, they value the reward more heavily than adults do” (Dobbs 54).

Not all teenagers try drugs and alcohol. However, because many teenagers will have to handle situations involving drugs, alcohol and sex it is a realistic part of many teen’s lives. When crafting a character, a writer should ask:

- Why does my character choose to try this?

- Why does she choose not to?

Not every teen character has to try these things, but the question should be asked of them. Not only is the chemistry in their brains screaming for them to try new and possibly dangerous things, their environments are too. For many teenagers these questions will come up, and that is where the writer has to come in and answer the why’s and how’s, otherwise the writer is not being true to her teenage character, nor her teenage audience.

7. Teenager’s brains are wired to go to bed later and get up later.

It is scientifically documented that teenager’s melatonin levels do not start working until up to two hours later than everyone else.[1] Therefore asking a teen to go to bed early and rise early is messing with their brain chemistry. If you have teenagers in your stories consistently waking up early and loving the sound of birdsong, there had better be a really good reason to back it up.

Every human being is different; therefore every teenager is different and deserves to be treated as an individual. We should treat our teen characters as individuals as well. Though steeped in research, these traits are not hard and fast rules. I suggest them as guidelines, something to test your character against for authenticity.

Try examining your teen character through the lens of this knowledge. Ask yourself if you’ve been authentic not only to the character as an individual, but to your character as a teenager. Your teenager should exhibit at least a few of these traits, and if your character seems more adult than teen, ask why. Perhaps there is a good reason and you can back it up in the story. Perhaps your character has had to grow up incredibly fast due to circumstances at home, such as living with a single parent or in a foster home. Consider ways in which some teen traits can still seep through. Perhaps an otherwise very responsible teen decides impulsively to just once sneak out of the house to spend time with friends. There are many ways in which you can be certain to remain true to a teenage character. Maybe your teenager gets bored and decides to take a late night drive, or climb into a boy’s window at 3 a.m. For some teenagers this can be an every now and again thing, for other teenagers they are made of impulsivity. Choosing how much impulsivity to add to your character is part of what makes your character an individual. The same goes for emotional reactions or risk taking behaviors.

8. Rise in compassion and awareness of the feelings of others.

While the brain is re-wiring, it is also making some changes that allow for compassion, understanding and empathy. Teens truly begin to understand the pain of others. It’s important to recognize that while teenagers can be difficult, they can also be understanding and empathetic.

Remember no one person is exactly like another; therefore one cannot really distill the essence of what it means to be an adolescent into a bullet list.

I hope this gives a touch of insight into the teenage psyche and perhaps as a result you have a few more tools with which to imbue your characters with a more authenticity and believability.

Jessica Denhart has an MFA from the Vermont College of Fine Arts and is a proud Dystropian. She writes Young Adult fiction and middle-grade, which varies from contemporary, to magical realism and “near-future quasi-dystopian”. When she was little she sometimes wanted to be a nurse or a fireman, but always wanted to be a writer. She ran away once, packing a basket full of her favorite books. She throws pottery, loves to crochet, and enjoys cooking and baking. Jessica lives in Central Illinois.

Jessica Denhart has an MFA from the Vermont College of Fine Arts and is a proud Dystropian. She writes Young Adult fiction and middle-grade, which varies from contemporary, to magical realism and “near-future quasi-dystopian”. When she was little she sometimes wanted to be a nurse or a fireman, but always wanted to be a writer. She ran away once, packing a basket full of her favorite books. She throws pottery, loves to crochet, and enjoys cooking and baking. Jessica lives in Central Illinois.

Follow Jessica on Twitter: @jdenhart

[1] Carskadon, Mary A., Christine Acebo, Gary S. Richardson, Barbara A. Tate, and Ronald Seifer. “An Approach to Studying Circadian Rhythms of Adolescent Humans.” Journal of Biological Rhythms 12 (1997): 278-89. Sage. Web. 7 Feb. 2012.

For more information:

Strauch, Barbara. The Primal Teen: What the New Discoveries about the Teenage Brain Tell Us about Our Kids. New York: Anchor, 2004. Print.

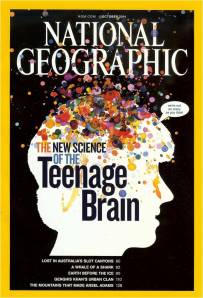

Dobbs, David. “Beautiful Teenage Brains.” National Geographic Oct. 2011: 36-59. Print.

Johnson, Sara B., Robert W. Blum, and Jay N. Giedd. “Adolescent Maturity and the Brain: The Promise and Pitfalls of Neuroscience Research in Adolescent Health Policy.” Journal of Adolescent Health 45 (2009): 216-21. Elsevier. Web. 4 Feb. 2012.

Music, Graham. Nurturing Natures: Attachment and Children’s Emotional, Sociocultural, and Brain Development. Hove, East Sussex: Psychology, 2011. Print.

Steinberg, Laurence D. Adolescence. 8th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2008. Print.

This blog post was brought to you as part of the March Dystropian Madness Blog Series.

By: Ingrid Sundberg,

on 4/4/2013

Blog:

Ingrid's Notes

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

March Dystropian Madness,

crafting authenticity,

Crafting Teen Characters,

The Teenage Brain,

YA,

Young Adult,

Writing Craft,

Writing for Teens,

VCFA,

Writing YA,

Add a tag

Making Peace with the Adolescent Pre-Frontal Cortex: Crafting Teen Characters with Respect and Authenticity

Part 2: Teen Traits (5 through 8)

By Jessica Denhart

In the part one of this article I talked about the teenage brain and the common teen traits of spotty memory, poor impulse control, the desire to do new things, and spending less time with family and more time with friends. Today we’ll talk about the last four traits that will help you craft authentic young adult characters.

In the part one of this article I talked about the teenage brain and the common teen traits of spotty memory, poor impulse control, the desire to do new things, and spending less time with family and more time with friends. Today we’ll talk about the last four traits that will help you craft authentic young adult characters.

5. Heightened Emotions

The one thing that is working completely in the teen brain is the limbic system, which deals with emotion, and is the part of the brain responsible for “pleasure seeking”. This seems to explain a lot about all of the heightened emotions that we deal with in our teen years. I remember feeling as though the entire world was ending when I had a fight with friends, or didn’t get asked out by the boy I liked.

6. Weighting risk and reward differently than adults.

Journalist David Dobbs points out that “Teens take more risks not because they don’t understand the dangers, but because they weigh risk versus reward differently. In situations where risk can get them something they want, they value the reward more heavily than adults do” (Dobbs 54).

Not all teenagers try drugs and alcohol. However, because many teenagers will have to handle situations involving drugs, alcohol and sex it is a realistic part of many teen’s lives. When crafting a character, a writer should ask:

- Why does my character choose to try this?

- Why does she choose not to?

Not every teen character has to try these things, but the question should be asked of them. Not only is the chemistry in their brains screaming for them to try new and possibly dangerous things, their environments are too. For many teenagers these questions will come up, and that is where the writer has to come in and answer the why’s and how’s, otherwise the writer is not being true to her teenage character, nor her teenage audience.

7. Teenager’s brains are wired to go to bed later and get up later.

It is scientifically documented that teenager’s melatonin levels do not start working until up to two hours later than everyone else.[1] Therefore asking a teen to go to bed early and rise early is messing with their brain chemistry. If you have teenagers in your stories consistently waking up early and loving the sound of birdsong, there had better be a really good reason to back it up.

Every human being is different; therefore every teenager is different and deserves to be treated as an individual. We should treat our teen characters as individuals as well. Though steeped in research, these traits are not hard and fast rules. I suggest them as guidelines, something to test your character against for authenticity.

Try examining your teen character through the lens of this knowledge. Ask yourself if you’ve been authentic not only to the character as an individual, but to your character as a teenager. Your teenager should exhibit at least a few of these traits, and if your character seems more adult than teen, ask why. Perhaps there is a good reason and you can back it up in the story. Perhaps your character has had to grow up incredibly fast due to circumstances at home, such as living with a single parent or in a foster home. Consider ways in which some teen traits can still seep through. Perhaps an otherwise very responsible teen decides impulsively to just once sneak out of the house to spend time with friends. There are many ways in which you can be certain to remain true to a teenage character. Maybe your teenager gets bored and decides to take a late night drive, or climb into a boy’s window at 3 a.m. For some teenagers this can be an every now and again thing, for other teenagers they are made of impulsivity. Choosing how much impulsivity to add to your character is part of what makes your character an individual. The same goes for emotional reactions or risk taking behaviors.

8. Rise in compassion and awareness of the feelings of others.

While the brain is re-wiring, it is also making some changes that allow for compassion, understanding and empathy. Teens truly begin to understand the pain of others. It’s important to recognize that while teenagers can be difficult, they can also be understanding and empathetic.

Remember no one person is exactly like another; therefore one cannot really distill the essence of what it means to be an adolescent into a bullet list.

I hope this gives a touch of insight into the teenage psyche and perhaps as a result you have a few more tools with which to imbue your characters with a more authenticity and believability.

Jessica Denhart has an MFA from the Vermont College of Fine Arts and is a proud Dystropian. She writes Young Adult fiction and middle-grade, which varies from contemporary, to magical realism and “near-future quasi-dystopian”. When she was little she sometimes wanted to be a nurse or a fireman, but always wanted to be a writer. She ran away once, packing a basket full of her favorite books. She throws pottery, loves to crochet, and enjoys cooking and baking. Jessica lives in Central Illinois.

Jessica Denhart has an MFA from the Vermont College of Fine Arts and is a proud Dystropian. She writes Young Adult fiction and middle-grade, which varies from contemporary, to magical realism and “near-future quasi-dystopian”. When she was little she sometimes wanted to be a nurse or a fireman, but always wanted to be a writer. She ran away once, packing a basket full of her favorite books. She throws pottery, loves to crochet, and enjoys cooking and baking. Jessica lives in Central Illinois.

Follow Jessica on Twitter: @jdenhart

[1] Carskadon, Mary A., Christine Acebo, Gary S. Richardson, Barbara A. Tate, and Ronald Seifer. “An Approach to Studying Circadian Rhythms of Adolescent Humans.” Journal of Biological Rhythms 12 (1997): 278-89. Sage. Web. 7 Feb. 2012.

For more information:

Strauch, Barbara. The Primal Teen: What the New Discoveries about the Teenage Brain Tell Us about Our Kids. New York: Anchor, 2004. Print.

Dobbs, David. “Beautiful Teenage Brains.” National Geographic Oct. 2011: 36-59. Print.

Johnson, Sara B., Robert W. Blum, and Jay N. Giedd. “Adolescent Maturity and the Brain: The Promise and Pitfalls of Neuroscience Research in Adolescent Health Policy.” Journal of Adolescent Health 45 (2009): 216-21. Elsevier. Web. 4 Feb. 2012.

Music, Graham. Nurturing Natures: Attachment and Children’s Emotional, Sociocultural, and Brain Development. Hove, East Sussex: Psychology, 2011. Print.

Steinberg, Laurence D. Adolescence. 8th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2008. Print.

This blog post was brought to you as part of the March Dystropian Madness Blog Series.

By: Ingrid Sundberg,

on 4/2/2013

Blog:

Ingrid's Notes

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Writing for Teens,

VCFA,

Writing YA,

March Dystropian Madness,

crafting authenticity,

Crafting Teen Characters,

The Teenage Brain,

YA,

Young Adult,

Writing Craft,

Add a tag

(Ingrid’s Note: Yup, it’s April. But I’ve still got three fabulous Dystropian posts to bring you. So it’s now April Dystropian Madness! )

Making Peace with the Adolescent Pre-Frontal Cortex: Crafting Teen Characters with Respect and Authenticity

Part 1: Teen Traits (1 through 4)

By Jessica Denhart