Just like Will Ferrell’s character in “Stranger Than Fiction,” you might find “yourself”—or your namesake, your avatar—spinning through a tale told by Ian McEwan, Margaret Atwood, Julian Barnes, Ken Follett, Hanif Kureishi, Will Self, Alan Hollinghurst, Zadie Smith, Tracy Chevalier, Joanna Trollope, or another of the 17 authors participating in a fundraising event for the UK medical charity Freedom From Torture.

Just like Will Ferrell’s character in “Stranger Than Fiction,” you might find “yourself”—or your namesake, your avatar—spinning through a tale told by Ian McEwan, Margaret Atwood, Julian Barnes, Ken Follett, Hanif Kureishi, Will Self, Alan Hollinghurst, Zadie Smith, Tracy Chevalier, Joanna Trollope, or another of the 17 authors participating in a fundraising event for the UK medical charity Freedom From Torture.

In this Literary Immortality Auction, participating authors have donated a character in a forthcoming work that will be named after auction winners.

Tracy Chevalier, author of the international bestseller The Girl with the Pearl Earring, said:

“I am holding open a place in my new novel for Mrs. (ideally a Mrs.) [your surname], a tough-talking landlady of a boarding house in 1850s Gold Rush-era San Francisco. The first thing she says to the hero is ‘No sick on my stairs. You vomit on my floors, you’re out.’ Is your name up to that?”

According the New York Times, Margaret Atwood is “offering the possibility of appearing either in the novel she is currently writing or in her retelling of Shakespeare’s ‘The Tempest,’ to be published as a Vintage Books series in 2016.”

Bestselling author Ian McEwan (Atonement) said:

“Forget the promises of the world’s religions. This auction offers the genuine opportunity of an afterlife. More importantly, bidding in the Freedom from Torture auction will help support a crucial and noble cause. The rehabilitation of torture survivors cannot be accomplished without expertise, compassion, time—and your money.”

Freedom from Torture notes on its site: “Seekers of a literary afterlife can place their bids online from 6pm this evening,” so get going.

Click here for your bid for immortality.

The real-time episode of the auction will take place at The Royal Institute of Great Britain in London on November 20th.

New Career Opportunities Daily: The best jobs in media.

By Robert Morrison

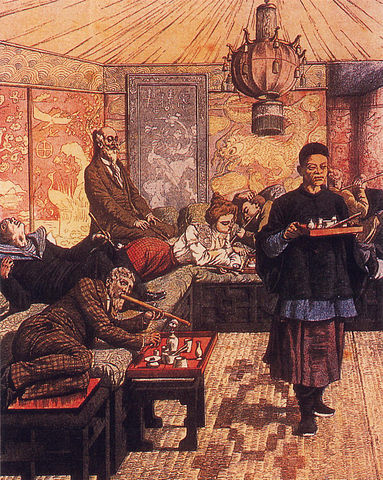

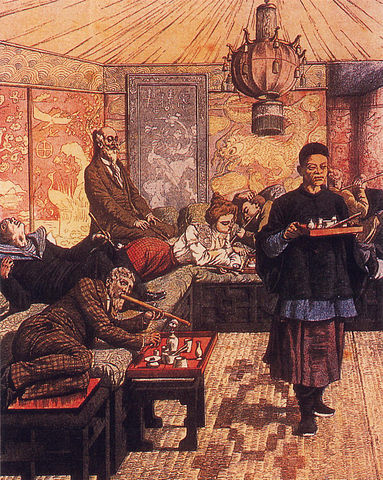

In The Metaphysics of Morals (1797), Immanuel Kant gives the standard eighteenth-century line on opium. Its “dreamy euphoria,” he declares, makes one “taciturn, withdrawn, and uncommunicative,” and it is “therefore… permitted only as a medicine.” Eighty-five years later, in The Gay Science (1882), Friedrich Nietzsche too discusses drugs, but he has a very different story to tell. “Who will ever relate the whole history of narcotica?” he asks pointedly. “It is almost the history of ‘culture’, of so-called high culture.” What caused this seismic shift in attitude? How did opium, in less than a century, pass from a drug understood primarily as a medicine to a drug used and abused recreationally, not just in “high culture”, but across the social strata?

The short answer is Thomas De Quincey. In his Confessions of an English Opium-Eater, first published in the London Magazine for September and October 1821, he transformed our perception of drugs. De Quincey invented recreational drug-taking, not because he was the first to swallow opiates for non-medical reasons (he was hardly that), but because he was the first to commemorate his drug experience in a compelling narrative that was consciously aimed at — and consumed by — a broad commercial audience. Further, in knitting together intellectualism, unconventionality, drugs, and the city, De Quincey mapped in the counter-cultural figure of the bohemian. He was also the first flâneur, high and anonymous, graceful and detached, strolling through crowded urban sprawls trying to decipher the spectacles, faces, and memories that reside there. Most strikingly, as the self-proclaimed “Pope” of “the true church on the subject of opium,” he initiated the tradition of the literature of intoxication with his portrait of the addict as a young man. De Quincey is the first modern artist, at once prophet and exile, riven by a drug that both inspired and eviscerated him.

The short answer is Thomas De Quincey. In his Confessions of an English Opium-Eater, first published in the London Magazine for September and October 1821, he transformed our perception of drugs. De Quincey invented recreational drug-taking, not because he was the first to swallow opiates for non-medical reasons (he was hardly that), but because he was the first to commemorate his drug experience in a compelling narrative that was consciously aimed at — and consumed by — a broad commercial audience. Further, in knitting together intellectualism, unconventionality, drugs, and the city, De Quincey mapped in the counter-cultural figure of the bohemian. He was also the first flâneur, high and anonymous, graceful and detached, strolling through crowded urban sprawls trying to decipher the spectacles, faces, and memories that reside there. Most strikingly, as the self-proclaimed “Pope” of “the true church on the subject of opium,” he initiated the tradition of the literature of intoxication with his portrait of the addict as a young man. De Quincey is the first modern artist, at once prophet and exile, riven by a drug that both inspired and eviscerated him.

The Confessions warned some early readers off opium, as De Quincey claimed he intended. “Better, a thousand times better, die than have anything to do with such a Devil’s own drug!” Thomas Carlyle commented after reading the work, while De Quincey’s erstwhile friend and fellow opium addict Samuel Taylor Coleridge insisted that he read the Confessions with “unutterable sorrow…The writer with morbid vanity, makes a boast of what was my misfortune.” But for many other readers, De Quincey’s account of opium was an invitation to experimentation — his drugged highs almost irresistible, and the gothic gloom of his lows even more so. Within months of publication, John Wilson, De Quincey’s closest friend and the lead writer for the powerful Blackwood’s Magazine, heard alarming reports of people recklessly attempting to emulate De Quincey’s drug experiences. “Pray, is it true…that your Confessions have caused about fifty unintentional suicides?” he inquires in a flamboyant Blackwood’s sketch. “I should think not,” the Opium Eater replies indignantly. “I have read of six only; and they rested on no solid foundation.”

Others, however, did not find the situation funny. One doctor recorded a sharp increase in the number of people overdosing on opium “in consequence of a little book that has been published by a man of literature.” The authors of The Family Oracle of Health (1824) were even angrier. “The use of opium has been recently much increased by a wild, absurd, and romancing production, called the Confessions of an English Opium-Eater,” they declared. “We observe, that at some late inquests this wicked book has been severely censured, as the source of misery and torment, and even of suicide itself, to those who have been seduced to take opium by its lying stories about celestial dreams, and similar nonsense.”

Others, however, did not find the situation funny. One doctor recorded a sharp increase in the number of people overdosing on opium “in consequence of a little book that has been published by a man of literature.” The authors of The Family Oracle of Health (1824) were even angrier. “The use of opium has been recently much increased by a wild, absurd, and romancing production, called the Confessions of an English Opium-Eater,” they declared. “We observe, that at some late inquests this wicked book has been severely censured, as the source of misery and torment, and even of suicide itself, to those who have been seduced to take opium by its lying stories about celestial dreams, and similar nonsense.”

De Quincey was characteristically divided on the influence of his Confessions. In the work itself he states that his primary objective is to reveal the powers of the drug: opium is “the true hero of the tale,” and “the legitimate centre on which the interest revolves.” Yet in Suspiria de Profundis (1845), the sequel to the Confessions, he maintains that its “true hero” is, not opium, but the powers of his imaginative — and especially of his dreaming — mind. Elsewhere, De Quincey denied the charges that his writings had encouraged drug abuse: “Teach opium-eating! – Did I teach wine drinking? Did I reveal the mystery of sleeping? Did I inaugurate the infirmity of laughter? . . . My faith is – that no man is likely to adopt opium or to lay it aside in consequence of anything he may read in a book.” In still other instances De Quincey regarded his drug habit as a source of amusement. “Since leaving off opium,” he noted wryly, “I take a great deal too much of it for my health.” More commonly, though, he was horrified by the damage it was inflicting. “It is as if ivory carvings and elaborate fretwork and fair enamelling should be found with worms and ashes amongst coffins and the wrecks of some forgotten life,” he wrote in the midst of one of his many attempts to abjure the drug.

De Quincey’s account of his opiated experiences has left on indelible print on the literature of addiction, and modern commentators continue to grapple with his legacy, though there is no agreement on whether he should be blamed, or absolved, or lauded. In Romancing Opiates (2006), Theodore Dalrymple lambasts him. “In modern society the main cause of drug addiction…is a literary tradition of romantic claptrap, started by Coleridge and De Quincey, and continued without serious interruption ever since,” he asserts. “This claptrap is the main source of popular and medical misconceptions on the subject.” Will Self, however, argues vigorously against such a view. “The truth is that books like…De Quincey’s Confessions no more create drug addicts than video nasties engender prepubescent murderers,” he declares in Junk Mail (1995). “Rather, culture, in this wider sense, is a hall of mirrors in which cause and effect endlessly reciprocate one another in a diminuendo that tends ineluctably towards the trivial.”

Ann Marlowe takes yet another position on the “brilliant, unsurpassed Confessions.” “Ever since I read De Quincey in my early teens,” she writes in How to Stop Time (1999), “I’d planned to try opium,” a far more direct account of “cause and effect” than Self’s halls of opium smoke and mirrors. Yet Marlowe and Self agree that they were both drawn to the drug because of its close association with intellectualism and insight, for both “hoped to pass through the portals of dope” into the “honoured company” of Coleridge and De Quincey. Such reasoning, Marlowe recognizes later, is “the sorriest cliche,” or what Dalrymple would call “claptrap”. But these accounts make plain that De Quincey’s potent memorialization of his drug experience has proven at least as seductive as the drug itself. His Confessions loosed the recreational genies from the medicine bottle and made opiates for the masses. De Quincey was lucky. The drug battered him, but it never finally defeated his creativity or his resolve. Many have not been that fortunate. Diagnosed at aged twenty with an opiate addiction, Self was “appalled to discover that I was not a famous underground writer. Indeed, far from being a writer at all, I was simply underground.”

Robert Morrison is Queen’s National Scholar at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario, where he maintains the Thomas De Quincey homepage. For Oxford World’s Classics, he has edited (with Chris Baldick) The Vampyre and Other Tales of the Macabre, as well as Thomas De Quincey’s Confessions of an English Opium-Eater and Other Writings, and three essays On Murder. Morrison is the author of The English Opium-Eater: A Biography of Thomas De Quincey, which was a finalist for the James Black Memorial Prize. His annotated edition of Jane Austen’s Persuasion was published by Harvard University Press. For Palgrave, he edited (with Daniel Sanjiv Roberts) a collection of essays entitled Romanticism and Blackwood’s Magazine: ‘An Unprecedented Phenomenon’. Read his previous blog posts: “De Quincey’s fine art” and “Vampyre Rising.”

For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics has made available the broadest spectrum of literature from around the globe. Each affordable volume reflects Oxford’s commitment to scholarship, providing the most accurate text plus a wealth of other valuable features, including expert introductions by leading authorities, voluminous notes to clarify the text, up-to-date bibliographies for further study, and much more. You can follow Oxford World’s Classics on Twitter and Facebook.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles articles on the OUPblog via email RSS

Image Credits: (1) Thomas de Quincey – Project Gutenberg eText 19222 via Wikimedia Commons. (2) “A New Vice: Opium Dens in France”, cover of Le Petit Journal, 5 July 1903. via Wikimedia Commons. (3) Cropped screenshot from the film trailer Confessions of an Opium Eater (1962) via Wikimedia Commons

The post De Quincey’s wicked book appeared first on OUPblog.

Novelist Hilary Mantel has won the £50,000 (roughly $65,175) Man Booker Prize for Bring up the Bodies, the second time she has taken the award.

Novelist Hilary Mantel has won the £50,000 (roughly $65,175) Man Booker Prize for Bring up the Bodies, the second time she has taken the award.

Follow the links below to read excerpts from all the authors on the longlist. “I merely wanted novels that they would not leave behind on a beach,” said judicial chair Sir Peter Stothard, leading a panel of judges that included Dinah Birch, Amanda Foreman, Dan Stevens and Bharat Tandon.

If you want more books, we made similar literary mixtapes linking to free samples of the 2012 National Book Award Finalists, 2012 Man Booker Longlist, the Best Science Fiction of the Year the Believer Book Award nominees, the 2012 Orwell Prize shortlist, the LA Times Book Prize winners, and the Best Business Books of the Year.

continued…

New Career Opportunities Daily: The best jobs in media.

The longlist for the 2012 Man Booker Prize has been revealed, a list that includes four debut novelists. We’ve researched these 12 finalists, finding free samples of these books scattered across the world–a number of titles aren’t even available in the U.S. yet.

The longlist for the 2012 Man Booker Prize has been revealed, a list that includes four debut novelists. We’ve researched these 12 finalists, finding free samples of these books scattered across the world–a number of titles aren’t even available in the U.S. yet.

Follow the links below to read excerpts from these books. The shortlist will be revealed on September 11th and the winner will be announced on October 16th.

If you want more books, we made similar literary mixtapes linking to free samples of the Believer Book Award nominees, the 2012 Orwell Prize shortlist, the LA Times Book Prize winners, the Orion Book Award Finalists, Best Mystery Books of 2011, the Best Illustrated Children’s Books of 2011 and the Most Overlooked Books of 2011.

continued…

New Career Opportunities Daily: The best jobs in media.

Just like Will Ferrell’s character in “Stranger Than Fiction,” you might find “yourself”—or your namesake, your avatar—spinning through a tale told by Ian McEwan, Margaret Atwood, Julian Barnes, Ken Follett, Hanif Kureishi, Will Self, Alan Hollinghurst, Zadie Smith, Tracy Chevalier, Joanna Trollope, or another of the 17 authors participating in a fundraising event for the UK medical charity Freedom From Torture.

Just like Will Ferrell’s character in “Stranger Than Fiction,” you might find “yourself”—or your namesake, your avatar—spinning through a tale told by Ian McEwan, Margaret Atwood, Julian Barnes, Ken Follett, Hanif Kureishi, Will Self, Alan Hollinghurst, Zadie Smith, Tracy Chevalier, Joanna Trollope, or another of the 17 authors participating in a fundraising event for the UK medical charity Freedom From Torture.

Novelist Hilary Mantel has won the £50,000 (roughly $65,175) Man Booker Prize for Bring up the Bodies, the second time she has

Novelist Hilary Mantel has won the £50,000 (roughly $65,175) Man Booker Prize for Bring up the Bodies, the second time she has