By Simon Thomas

Gwyneth Paltrow and Chris Martin (better known as an Oscar-winning actress and the Grammy-winning lead singer of Coldplay respectively) recently announced that they would be separating. While the news of any separation is sad, we can’t deny that the report also carried some linguistic interest. In the announcement, on Paltrow’s lifestyle site Goop, the pair described the end of their marriage as a “conscious uncoupling.” So … what does that mean?

The phrase was picked up by journalists, commentators, and tweeters around the world. Some called it pretentious, some thought it wise, others simply didn’t know what was going on. Let’s have a look into the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) and see what we can learn about these words.

Conscious is perhaps the less controversial word of the pair. A look through the Oxford Thesaurus of English brings up adjectives like aware, deliberate, intentional, and considered. But did you know that the earliest recorded use of conscious related only to misdeeds? The OED currently dates the word to 1573, with the definition “having awareness of one’s own wrongdoing, affected by a feeling of guilt.” This sense is now confined to literary contexts, but it was only a few decades before the general sense “having knowledge or awareness; able to perceive or experience something” became common. The idea of it being used as an adjective referring to a deliberate action came later, in 1726, according to the OED’s current research.

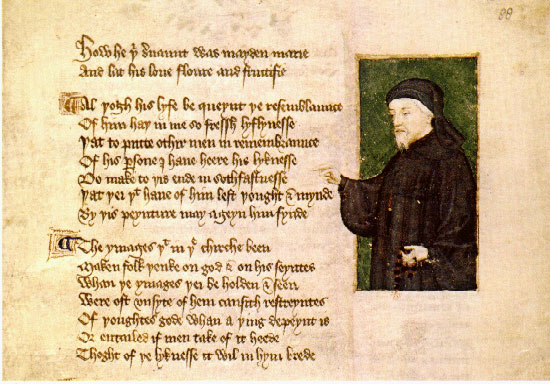

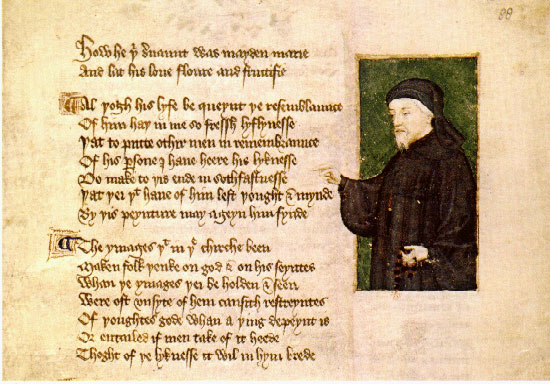

Portrait of Geoffrey Chaucer by Thomas Hoccleve in the Regiment of Princes

The verb uncouple has an intriguing history. The current earliest evidence in the OED dates to the early fourteenth century, where it means “to release (dogs) from being fastened together in couples; to set free for the chase.” Interestingly, this is found earlier than its opposite (“to tie or fasten (dogs) together in pairs”), currently dated to c.1400 in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. In c.1386, in the hands of Chaucer and “The Monk’s Tale,” uncouple is given a figurative use:

He maked hym so konnyng and so sowple

That longe tyme it was er tirannye

Or any vice dorste on hym vncowple.

The wider meaning “to unfasten, disconnect, detach” arrives in the early sixteenth century, and that is where things rested for some centuries.

The twentieth century saw another couple of uncouples – one of which is applicable to the Paltrow-Martins, and one of which refers to a very different field. In 1948, a biochemical use is first recorded – which the OED defines “to separate the processes of (phosphorylation) from those of oxidation.” But six years earlier, an American Thesaurus of Slang includes the word as a synonym for “to divorce,” and this forms the earliest example found in the OED sense defined as “to separate at the end of a relationship.” Other instances of uncouple meaning “to split up” can be found in a 1977 Washington Post article and one from the Boston Globe in 1989.

So, despite all the attention given to the term “conscious uncoupling,” people have been uncoupling in exactly the same way as Gwyneth and Chris – and using the same word – since at least 1942. So perhaps not quite as controversial as some commentators suggested.

A version of this article originally appeared on the OxfordWords blog.

Simon Thomas blogs at Stuck-in-a-Book.co.uk.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only language articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image: Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Word histories: conscious uncoupling appeared first on OUPblog.

By Andrew Hadfield

Writing to his friend Dudley Carleton on 17 January 1599, the enthusiastic correspondent John Chamberlain (1553-1628) noted that “Spencer, our principall poet, coming lately out of Ireland, died at Westminster on Satturday last.” Chamberlain’s testimony confirms that Spenser died on 13 January. Chamberlain is a good recorder of court gossip and a barometer of what interested the upper echelons of London society. Edmund Spenser’s death is reported at the end of a letter listing the marriages and deaths of people the two correspondents both knew. We have no idea what led to Spenser’s death. The few accounts we have of his last days, all of which are brief and limited in detail, fail to provide clues of his state of health or mind. The trouble is that different explanations are equally plausible. Spenser’s circumstances might have had an impact on the timing of his death, or he might simply have died of natural causes, being neither especially young nor particularly old to die in an era of relatively primitive medical practice, bad diet, and the absence of comfort when winter weather was extreme. The most striking fact is that he died within three weeks of leaving Ireland, having left in grim circumstances.

By the time of his death Spenser was undoubtedly the most celebrated and important poet writing in English. He had assumed the mantle of Sir Philip Sidney, the most important aristocratic poet before Spenser; William Shakespeare wasn’t really in Spenser’s league as a poet; John Donne and Ben Jonson were yet to emerge as poets of stature. Yet, according to Jonson, talking to William Drummond some years later Spenser “died for lack of bread.” It is unlikely that this is true as Spenser had a generous pension from the queen of £50 per annum, and had carried some letters from the desperate colonists in Ireland to the Privy Council who, surely, had not stood by and let him starve. Perhaps payments were delayed; more likely Jonson’s comments are a reflection on the catastrophic loss that Spenser had suffered when his estate was over-run in Ireland and he was forced to flee. Legend has it that Spenser and his family escaped via a cave beneath his house at Kilcolman, but it is more likely that they had already fled to the safety of Cork city before heading for London. Spenser, it seems, was recognised as an unfortunate writer, one whose talent had taken him from relatively obscure origins to unprecedented heights, only to cheat him at the last.

Cave at Kilcolman. Courtesy of Andrew Hadfield.

But if Spenser was a detested colonist in Ireland and overlooked by the authorities in England, he was celebrated and lauded by his fellow poets in London. He was buried at the end of January in Westminster Abbey. William Camden has provided the best account of what must have been a moving and significant event. Camden, like Jonson, provides evidence in his short sketch of Spenser’s life and death that Spenser was perceived to have been harshly treated in life and that he died in poverty, a belief shared by most who commented on the last months of Spenser’s life in the early seventeenth century. Camden writes:

But by a Fate which still follows Poets, he always wrastled with poverty, though he had been Secretary to the Lord Grey, Lord Deputy of Ireland. For scarce had he there settled himself in a retired Privacy, and got Leisure to write, when he was by the Rebels thrown out of his Dwelling, plundered of his Goods, and returned into England a poor man, where he shortly after died, and was interred at Westminster, near to Chaucer, at the Charge of the earl of Essex; his hearse being attended by Poets, and mournfull Elegies and Poems with the Pens that wrote them thrown into his Tomb.

The area where Spenser was thought to be buried was dug up in the inter-war period but there was no trace of the body, poems or pens.

Many of these elegies would have reappeared in print, such as that by the young Cornish poet, Charles Fitzgeoffrey (1593-1636), who had already praised Spenser as the heir of Homer in his long lament for Sir Francis Drake (1596), and who now cast him as the English Virgil in a series of Latin tributes published in 1601. There were poems from more established writers such as Nicholas Breton, whose “An Epitaph Upon Poet Spencer,” with such memorable lines as, “Sing a dirge on Spencers death, / Till your soules be out of breath,” was published as the last poem in the volume, Melancholike Humours (1600). It is also likely that another elegy written for the occasion was the unpublished Latin epigram by William Alabaster (1567-1640), ‘In Edouardum Spencerum, Britannicae poesios facile principem,’ which does sound as if it were designed for the funeral:

Fors qui sepulchre conditur siquis fuit If who’s buried here,

Quaeris uiator, dignus es qui rescias. you ask passerby, you deserve to hear.

Spencerus istic conditur, siquis fuit Spenser is buried here. If who he is

Rogare pergis, dignus es qui nescias. you go on to ask, you don’t deserve to know.

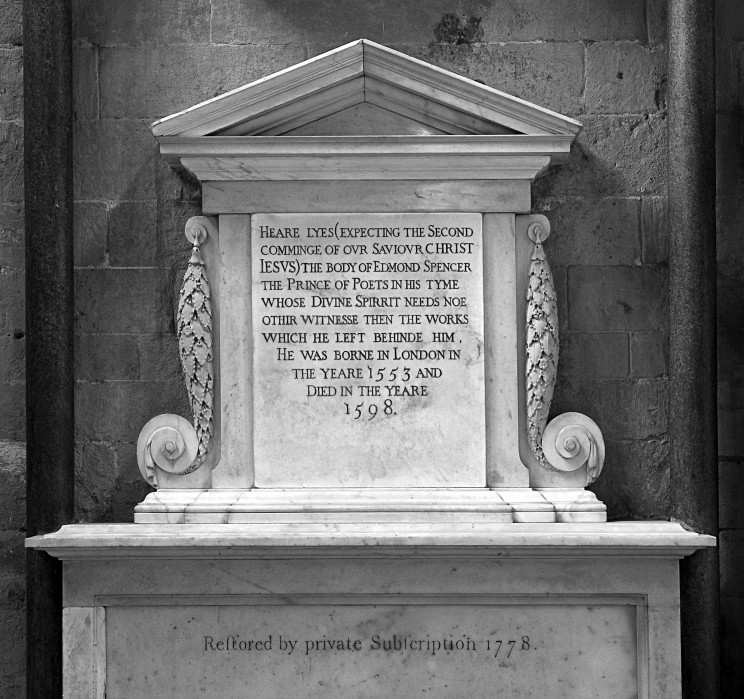

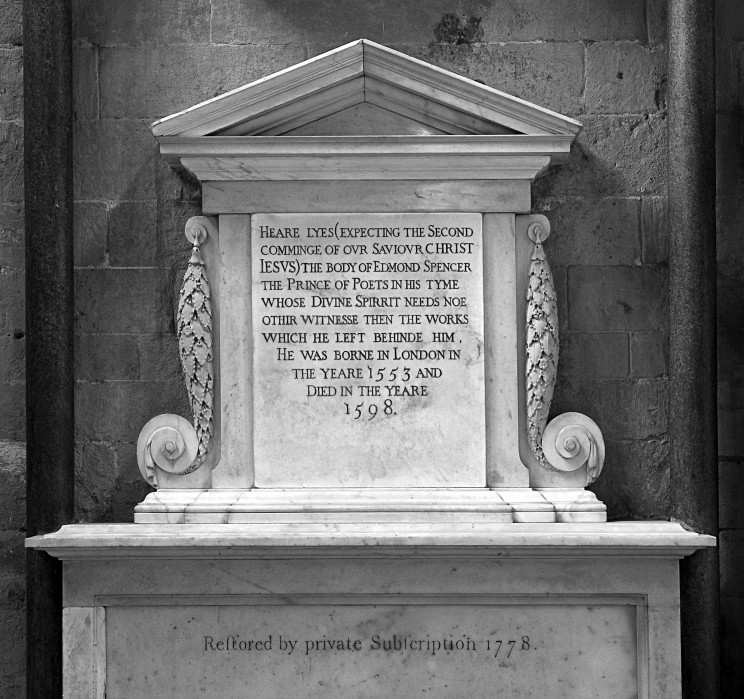

The decision to bury Spenser near to Chaucer was a first step towards defining the collection of graves of writers in the south transept, Poets’ Corner. The area was not formally designated as the resting place for the nation’s most celebrated writers until the eighteenth century, but Spenser, generally accepted as the natural heir of Chaucer, was buried next to his most illustrious predecessor, a decision that started a trend. By 1723 the site contained the graves and monuments of a number of illustrious poets: Samuel Butler, Abraham Cowley, Michael Drayton, John Dryden, Thomas Shadwell and others. A monument was eventually erected by Lady Anne Clifford. Clifford, who had been taught by Samuel Daniel and was later pictured alongside her books, which included Spenser, was clearly eager to advertise her role as a reader and patron of English poetry. The monument was built by Nicholas Stone (1585/8-1647), who noted in his account book, “I also mad a moument for Mr. Spencer, the pouett and set it up at Westmester for which the contes of Dorsett payed me 40£.” Stone was a distinguished master mason, “the best English sculptor of his generation,” who later designed John Donne’s tomb in St. Paul’s Cathedral, helped build the Banqueting House in Whitehall from Inigo Jones’s designs, as well as Goldsmith’s Hall and a number of other funeral monuments and prominent country houses. The inscription on the now destroyed monument, gave erroneous dates for the poet’s birth and death, although, at least, his Christian name was spelled correctly:

HEARE LYES (EXPECTING THE SECOND

COMMINGE OF OVR SAVIOUR CHRIST

JESVS) THE BODY OF EDMOND SPENCER,

THE PRINCE OF POETS IN HIS TYME;

WHOSE DIVINE SPIRIT NEEDS NOE

OTHIR WITNESSE THEN THE WORKS

WHICH HE LEFT BEHINDE HIM.

HE BORNE IN LONDON IN

THE YEARE 1510. AND

DIED IN THE YEARE

1596.

Spenser monument, Westminster Abbey. Reproduced with kind permission of Westminster Abbey.

According to the antiquarian John Dart (d.1730), it was not an impressive edifice, a pointed contrast to its replacement. Recommending a tour of the poets’ monuments in the South Transept, Dart notes that:

[T]he first Tomb you come at is a rough one, of coarse Marble and looks by the Moisture and Injury of the Weather, and the Nature of the Stone, much older than it is. This, whose Form is here erected to the Memory of Mr. Edmond Spencer, a Man of great Learning and such luxuriant Fancy, that his Works abound with as great Variety of Images (and curious tho’ small Paintings) as either our own or any Language can afford in any Author.

Dart, citing Camden as an authority, reproduces a Latin epitaph that was supposedly on the original tomb, although it is now no longer visible. Dart translates it as:

Here lies Spenser next to Chaucer, next to

him in talent as next to him in death. O Spenser,

here next to Chaucer the poet, as a poet you are

buried; and in your poetry you are more permanent

than in your grave. While you were alive, English

poetry lived and approved you; now you are dead,

it too must die and fears to.

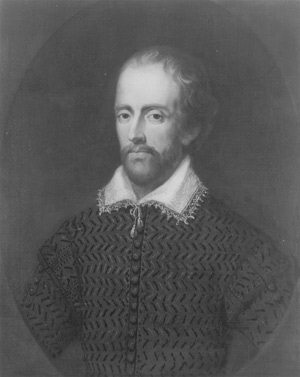

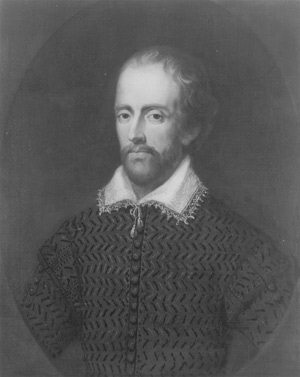

Chesterfield portrait of Edmund Spenser. Reproduced with kind permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London.

None of this remains and Dart and Camden are the only witnesses to the original. The monument was important enough to feature in John Hughes’ edition of his works, in an engraving by Loius de Guernier. The edition, the first illustrated edition of Spenser’s works, included a picture of four well-dressed figures, two men and two women, discussing the inscription on Spenser’s tomb, obviously in the absence of a portrait of the poet .

Poets’ Corner was taking shape as a place in the public imagination, started through the union of Chaucer and Spenser. The monument decayed and crumbled away and was replaced in 1778 by a more durable marble structure in the same style, built by

William Mason (1725-97), the poet and garden designer, who had been a fellow at Pembroke College. Mason also gave the college a copy of the Chesterfield portrait which hangs in the hall. Now, there was a clear desire to know what Spenser had looked like, unfortunately a long time after any evidence could be recovered.

Andrew Hadfield is Professor of English at the University of Sussex and the author of Edmund Spenser: A Life (OUP, 2012). He is the author of a number of works on early modern literature, including Shakespeare and Republicanism; Literature, Travel and Colonialism in the English Renaissance, 1540-1625; Spenser’s Irish Experience: Wilde Fruyt and Salvage Soyl; and Literature, Politics and National Identity: Reformation to Renaissance. He was editor of Renaissance Studies (2006-11) and is a regular reviewer for The Times Literary Supplement. Read his previous blog post “10 facts and conjectures about Edmund Spenser” and “Edmund Spenser: ‘Elizabeth’s arse-kissing poet?’”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only literature articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post The death of Edmund Spenser appeared first on OUPblog.