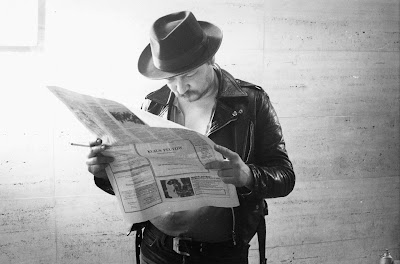

Yesterday was the 70th birthday of my favorite filmmaker,

Rainer Werner Fassbinder. He wasn't around to see it, having died at age 37, but I celebrated for him by watching

Querelle again. (I was tempted to do a

Berlin Alexanderplatz marathon today, but I do actually have to get some work done...)

I've written various things about Fassbinder over the years, so here's a roundup and then some 70th birthday thoughts:

Fassbinder isn't around anymore to make some wishes on his birthday, so I'll make a few in his stead...

Of course, my primary wish is for everybody on Earth to recognize and celebrate Fassbinder's genius. But I can be more specific:

My greatest wish is for a release of

Eight Hours Don't Make a Day. As far as I can tell, it's never been released on home video anywhere, and has hardly ever been shown since its premiere on German television in the early '70s.

Criterion is doing a good job of putting together excellent home video versions of many of the films. With luck, they'll solve whatever rights problems led them to put their wonderful

BRD Trilogy set out of print, and will continue releasing extra-features-rich versions of the major films, as they recently have with

The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant and

The Merchant of Four Seasons. I hope, given that they've been able to stream them on Hulu,

Effi Briest, Fox and His Friends, and

Mother Küsters are in line for similar treatment. I'd love to see a "Queer Fassbinder" set:

Fox, In a Year of 13 Moons, and

Querelle together, preferably with good commentaries and essays to help viewers work through the wonderful challenges those films offer.

Finally, we need someone to write a good, comprehensive biography. There are a few good Fassbinder books out there (my favorites of Thomas Elsaesser's

Fassbinder's Germany and Wallace Steadman Watson's

Understanding Rainer Werner Fassbinder, along with Juliane Lorenz's collection

Chaos as Usual: Conversations About Rainer Werner Fassbinder), but there's no good biography that I'm aware of. (Robert Katz's 1989 biography is an atrocity and shall not be spoken of.) Telling the story of Fassbinder's life day by day would be a tremendous, perhaps impossible, challenge, but the attempt would be worthwhile because it's so difficult to get a sense of how those days fit together — he would work on a film while also working on stage plays and radio plays, writing new scripts, getting financing for upcoming works, traveling to festivals — it's dizzying just to think about.

Fassbinder continues to offer riches to us even now. I wish, of course, that he'd made it to the age of an elder statesman (I'd trade significant portions of my anatomy to see what he would have done with digital cameras), but he lived so fast, so productively, and so brilliantly that though he died young, we're still working through his oeuvre in a way we aren't with even great filmmakers who lived to ripe old age. So happy birthday, RWF. We're celebrating even in your absence.

I attended a screening of Rainer Werner Fassbinder's 1980 film

Lili Marleen at the

Fassbinder: Romantic Anarchist series at Lincoln Center last weekend, and it was an extraordinary experience. This is one of Fassbinder's weirdest and in some ways most problematic films, a movie for which he had a relatively giant budget and got lots of publicity, but which has since become among the most hard-to-find Fassbinder films (which is really saying something!). Despite a lot of searching, I didn't come upon a reasonably-priced copy of it until I recently discovered an

Australian DVD (seemingly out of print now) that was a library discard.

The story of

Lili Marleen is relatively simple, and is very loosely based on the wartime experiences of

Lale Andersen, whose performance of the title

song was immensely popular, and whose book

Der Himmel hat viele Farben is credited in the film. A mildly talented Berlin cabaret singer named Willie (Hannah Schygulla) falls in love with a Jewish musician named Robert (Giancarlo Giannini), whose father (Mel Ferrer) is head of a powerful resistance organization based in Switzerland, and who does not approve of the love affair or Robert's proposal of marriage. A Nazi officer (Karl Heinz von Hassel) hears Willie perform one night, is captivated by her, and guides her into recording the song "Lili Marleen", which unexpectedly becomes a song beloved of all soldiers everywhere on Earth. Willie becomes a rich and famous star, summoned even by Hitler himself, while Robert continues to work for the resistance and ends up marrying someone else. By the end of the war, Robert is a great musician and conductor and Willie seems mostly forgotten, many of her friends dead or imprisoned, and Robert lost to her. She had no convictions aside from her love of Robert, but that love was not enough. (I should note here that there are interesting overlaps between the film and Kurt Vonnegut's great novel

Mother Night. But that's a topic for another day...)

I was surprised to find that Lincoln Center was using the German dub of the film rather than the English-language original (it was a multinational production, so English was the lingua franca, and, given the dominance of English-language film, presumably made it easier to market). It was interesting to see

Lili Marleen in German, but unfortunately the print did not come subtitled, and so Lincoln Center added subtitles by apparently having someone click on prepared blocks of text. The effect was bizarre: not only were the subtitles sometimes too light to read, but they were often off from what the actors were saying, and when the subtitler would get behind, they would simply click through whole paragraphs of text to catch up. My German's not great, but I was familiar with the film and can pick up enough German to know what was going on and where the subtitles belonged, but I missed plenty of details. The effect was to render the film more dreamlike and far less coherent in terms of plot and character relations than it actually is. Not a bad experience, though, as it heightened a lot of the effects Fassbinder seemed to be going for.

Afterward, I said to my companion, "That was like watching an anti-Nazi movie made in the style of Nazi movies." I'd vaguely had a similar feeling when I first watched the DVD, but it wasn't so vivid for me as when we watched the German version with terrible subtitling — my first experience of Nazi films was of unsubtitled 16mm prints and videotapes my WWII-obsessed father watched when I was a kid.

When I got home, I started looking through some of the critical writings on the film, and came across Laura J. Heins's contribution to

A Companion to Rainer Werner Fassbinder: "Two Kinds of Excess: Fassbinder and Veit Harlan", which interestingly compares

Lili Marleen to the aesthetics of

one of the most prominent of Nazi filmmakers (and a relative-by-marriage of Stanley Kubrick).

Lili Marleen was controversial when it was released, not only because it is probably Fassbinder's most over-the-top melodrama, a film that defies both the expectations of good taste and of mainstream storytelling, but also because it arrived at a time when what Susan Sontag dubbed (in February 1975)

"fascinating fascism" was on the wane (

The Damned was 1969,

Ilsa: She Wolf of the SS was October 1975, as if to bring everything Sontag described to an absurd climax) while interest in earnest representations of the Nazis and the Holocaust was on the rise (

Holocaust 1978,

The Tin Drum 1979,

The Last Metro 1980,

Playing for Time 1980,

Mephisto 1981,

Sophie's Choice 1982,

The Winds of War 1983, etc.).

Lili Marleen is much closer to

The Damned (a film Fassbinder

loved) in its effect than to the films with similar subject matter released in the years around it, and so its contrast from the prevailing aesthetic regime was stark, leading to what seems to have been in some critics utter revulsion. It's notable that

Mephisto, a film with very similar themes* and a significantly different aesthetic, could win an Oscar, but though Germany submitted

Lili Marleen to the Academy, it was not nominated — and I'd bet few people were surprised it was not.

Even though it exudes the signs of a pop culture aesthetic,

Lili Marleen can't actually be assimilated into the popular culture it was released into, partly because the aesthetic it's drawing from is passé and partly because it is deliberately at odds with conventional expectations. In a chapter on

Lili Marleen in

Fassbinder's Germany, Thomas Elsaesser

writes that "coincidence and dramatic irony are presented as terrible anticlimaxes. With its asymmetries and non-equivalences, the film disturbs the formal closure of popular narrative, while still retaining all the elements of popular story-telling."

At the time of its release, there was much handwringing about the ability of works of art to create a desire or nostalgia for fascism in audiences, and

Lili Marleen became Exhibit A. Heins quotes Brigitte Peucker: "One wonders whether, in

Lili Marleen, Fassbinder’s parodistic style is not unrecognizable as parody to most spectators, and whether his central alienation effect, the song itself, does not instead run the danger of drawing us in." This is absurd. Fassbinder's style is parodistic, but it's also much more than that — it is multimodal in its excess — and I have about as much ability to imagine an audience member getting a good ol' nostalgic lump in the throat and tear in the eye while watching it as I have the ability to imagine someone watching

Inglourious Bastards and mistaking it for

Night and Fog.

Heins paraphrases Peucker as apparently thinking that "the often repeated title song may ultimately generate more sentimental affect than irritation". I can't believe that, either. For those of us who are not especially misty-eyed about the long lost days of the 1,000-year Reich, the song becomes as grating as it does for the character of Robert (Giancarlo Giannini), who gets locked in a cell with a couple lines of the song playing over and over and over again. What begins as sentimentality becomes, through repetition, torture.

The song is repeated so much that even if it doesn't irritate, it is stripped of meaning, and that's central to the point of the story, as Elsaesser

describes:

When Willie says, "I only sing", she is not as politically naive or powerless as she may appear. Just as her love survives because she withdraws it from all possible objects and objectifications, so her song, through its very circularity, becomes impervious to the powers and structures in which it is implicated. Love and song are both, by the end of the film, empty signs. This is their strength, their saving grace, their redemptive innocence, allowing Fassbinder to acknowledge the degree to which his own film is inscribed within a system (of production, distribution and reception) already in place, waiting to be filled by an individual, who lends the enterprise the appearance of intentionality, design and desire for self-expression.

One of the things I love about

Lili Marleen is that its mode is utter and obvious kitsch, undeniable kitsch. It highlights the kitschiness not only of the Nazi aesthetic (which plenty of people have done, not least, though unintentionally, the Nazis themselves), but to some extent also of many movies about the Nazis. (I kept thinking of the awful TV mini-series

Holocaust while watching it this time, and Elsaesser

makes that connection as well.) We love to use the Nazis and the Holocaust for sentimental purposes, and representations of the Nazis and Holocaust often unintentionally veer off into

poshlost. To intentionally do so is dangerous, even as critique, because it is too easy to fall into parody and render fascism as something absurd and ridiculous, but not insidious. The genius of

Lili Marleen is that the insidiousness remains. It's what nags at us afterward, what lingers beneath the occasional laughter at the excess. There is a discomfort to this film, and it's not just the discomfort of undeniable parody — it is the discomfort of realizing how easily we can be drawn in to the structures being parodied: the suspense, the action, the breathless and improbable love story, the twists and turns, the pageantry, the displays of wealth and power. Our desires are easily teased, our expectations set like booby traps, and again and again those desires and expectations are frustrated and mercilessly mocked.

It's worth thinking about the place of anti-Semitism in

Lili Marleen (and Fassbinder's work generally), because this was also part of the uproar over the film, an uproar that was really a continuity of the

complaints about Fassbinder's extremely

controversial play

Garbage, the City, and Death. While not as brazenly playing with anti-Semitic imagery and language,

Lili Marleen does give us a very powerful Jewish patriarch in Robert's father, played by Mel Ferrer, a character that can be seen in a variety of ways — certainly, he is an impediment to Robert and Willie's romance (clearly wanting his son to marry a nice Jewish girl), but I also think that Ferrer's performance gives him some warmth and grace that the Nazi characters lack. Nonetheless, while

Lili Marleen is very obviously an anti-Nazi film, it's not so obviously an anti-anti-Semitic film (though there is a quick shot of a concentration camp, and Willie redeems herself by sneaking evidence of the camps out of Poland). Heins writes:

It cannot, of course, be concluded that the Absent One of all of Fassbinder’s films is The Jew, or that the sense of danger created by an unseen presence is racialized or nationalized, as it is in Harlan’s film [Jud Süss]. The malevolent other of Fassbinder’s films is more properly patriarchy and the police state, acting in the service of a repressive bourgeois order. In the case of Lili Marleen, however, we must conclude that Fassbinder did fail to effectively counteract the Harlanesque paranoid delusion of total Jewish power, if only because The Jew in this film is described as capitalist patriarchy’s main representative.

That point is astute, though for me it highlight the (sometimes dangerous) complexity of

Lili Marleen: by employing certain features of Nazi storytelling, by putting clichés (aesthetic, narrative, political) at the center of his technique, and by seeking to wed this to the sort of anti-capitalist, anti-normative-family ideas common to his work from the beginning, Fassbinder ends up in a bind, one that forces him to trust that the various opposing forces render all the clichés hollow enough that performing and representing them does not give them new validity or justification — that the paranoia and delusion remain legible as paranoia and delusion. I think they do, but I feel less certain of that than the certainty I feel against the old accusations of glamourizing Nazism.

In addition to the title song,

Lili Marleen includes an ostentatiously schmaltzy score by Fassbinder's frequent collaborator Peer Raben. It's schmaltzy, but also very sly — as Roger Hillman points out on the Australian DVD commentary, Raben includes brief homages to composers and works that the Nazis would not have looked fondly on, such as Saint-Saëns'

Samson and Delilah. This technique is similar to the film's entire strategy: to booby-trap what on the surface is an overwrought deployment of old tropes.

Finally, a note on the acting: sticking with the concept of the film as a whole, the acting is generally a bit off: sometimes wooden, sometimes unconvincingly emotional. (It's acting a la Brecht via Sirk via Fassbinder.) The more I watch it, though, the more taken I am by Hannah Schygulla's performance. On the surface, it's an appropriately "bad" performance, one redolent of the acting style of melodramas in general and Nazi melodramas in particular. And yet Schygulla's great achievement is to find nuance within that — hers is not a parodic performance, though it easily could have veered into that. Instead, while abiding by the terms of melodramatic acting, it also gives us a transformation: Willie starts out awkward, not particularly talented, a sort of country bumpkin ... and she becomes a poised, distant, sculpted icon ... and then a refugee from all she has ever known and loved. There's still a sense of possibility at the end, though, and one Schygulla's performance is vital for: a sense that Willie may reinvent herself, may find, in this newly ruined world, a path toward new life.

Elsaesser

suggests that

Lili Marleen can be seen within the context of some of the other films Fassbinder made around it:

the three films of the BRD trilogy — shot out of sequence — are held together by the possibility that they form sequels. If we add the film that was made between Maria Braun and Lola, namely Lili Marleen which clearly has key themes in common with the trilogy, then Lili Marleen's status in the series might be that of a "prequel" chronologically: 1938-1946 Lili Marleen, 1945-1954 Maria Braun, 1956 Veronika Voss, 1957 Lola. Four women, four love stories, four ambiguous gestures of complicity and resistance.

It could be a tagline for so many of Fassbinder's films, not the least

Lili Marleen: Ambiguous gestures of complicity and resistance. For a world entering the era of Thatcher, Kohl, and (especially) Reagan,

Lili Marleen was a most appropriate foil.

-------------------

*In one scene of Fassbinder's film, Willie looks through a magazine and we quickly glance a picture of

Gustaf Gründgens as Mephistopheles.

RogerEbert.com has just published a good overview of the work of Rainer Werner Fassbinder by Godfrey Cheshire,

"Regarding R.W. Fassbinder: Letter to a Young Cinephile", inspired by the major, two-part Fassbinder retrospective at Lincoln Center in New York,

currently underway and then continuing in the fall. If you're in traveling distance of New York City and you have any interest in film, you should try to go to some of these. (Also,

the Mizoguchi series at the Museum of the Moving Image. I can't get to the city until both festivals are over, and so my jealousy of you will be intense, though at least I may get to see some of the Mizoguchis at

Harvard Film Archive's similar series.)

I've written about Fassbinder here

before, and created a

video essay last summer for Press Play about Fassbinder's earliest films. He is simply, completely, unquestionably my favorite filmmaker, the one whose work most deeply and consistently fascinates me, challenges me, and engages me. This is a personal response, and I don't expect anyone else to be as besotted as I am with RWF, especially given how idiosyncratic a lot of his work is, but on the other hand I am suspicious of anyone who claims to have an interest in cinema and is not in some way touched by the most accessible of his works — indeed, I'm not sure I know how to communicate with someone who gets nothing from either

Fear Eats the Soul or

The Marriage of Maria Braun; I would feel alienated at a certain level from any such person.

Godfrey Cheshire gets at some of the important qualities of Fassbinder's work, and proposes some reasons for Fassbinder's relative obscurity and neglect, especially among younger cinephiles and filmmakers. As Cheshire notes, it's certainly possible that some of that obscurity and neglect results from feeling overwhelmed in the face of Fassbinder's massive output and wondering

where to begin. That obstacle can be relatively easily overcome, and it's not like other, hugely influential filmmakers such as John Ford and Alfred Hitchcock created small

oeuvres. No, the problem is more with the kinds of films that Fassbinder made and the way he made them: "There’s something else, which I’ll approach via a musical analogy in the form of a question: Why aren’t the Sex Pistols played on rock radio?"

In a sense, Fassbinder was international cinema’s closest equivalent to punk rock, which reached its peak during the same years that his career did. In the previous decades, Europe’s art cinemas (French, Italian, Swedish, Polish, etc.) had developed in the direction of refined aestheticism and intellectuality. Fassbinder’s cinema initially came as a shock because it was just the opposite: rude, raw and aggressively non-pretty. Its settings were seedy, its characters low-lifes, its actors often plug-ugly (except when they were beautiful). Yet this was just the starting point. As he rocketed forward, it was if Sid Vicious morphed into Beethoven.

This seems to me to point to some of the challenge of Fassbinder for today's audiences, particularly as the "refined aestheticism and intellectuality" of the 1960s European art cinema petrified into a template for the Meaningful Movie. I think Cheshire's actually wrong in identifying the settings, characters, and actors as the challenge; the bourgeois high-art sensibility loves a romp in the slums. The problem for the films' popularity is aesthetic and ideological.

Love Is Colder than Death was booed in Berlin because it didn't present any sort of noble vision of the working classes and it skewered the pretensions of the revolutionary class. If I'm paying good money to go to a prestigious film festival, I want my taste lauded, I want my

weltanschauung confirmed, I want to know that I'm not just a good person, but one of the best — someone deserving of his position, not just a happenstance carrier of privilege, a vector of social disease. (In this approach to his audience, I think Fassbinder links to

the plays of Wallace Shawn.)

Cheshire is correct (and not unique) in seeing Fassbinder's major theme being exploitation, both the systems that encourage and perpetuate it and the personality flaws that feast on it. It's insightful to connect this to Fassbinder's lifelong obsession with the effect of the Nazi era on the German psyche. (That connection and obsession is so complex that I can't possibly even begin to untangle it all here. Thomas Elsaesser's

Fassbinder's Germany does an excellent job of some of that work.) Cheshire points to one of the central appeals of Fassbinder's work for me: his unwillingness to let anyone off the hook, no matter their social standing or marginal status:

The two melodramas focused on gay characters in his second period, "Fox and His Friends" (in which Fassbinder plays a working-class gay guy who wins a lottery that makes him a target of more well-heeled types) and "The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant" (a tale of lesbian betrayals), depict gays as every bit as exploitive as their straight counterparts, and both films duly drew protests from gay political groups.

Fox and His Friends may be my favorite Fassbinder movie, if such a statement can even be meaningful (how can I have

one favorite?!). Fassbinder was

intersectional before the word became vogue, but his intersectional analysis was caustic and cynical rather than ennobling, because ultimately his analysis was about the corruptions of power. Much as I want whatever marginalities I might inhabit to make me into a good person deserving of pity and love, in truth I'm probably just as awful as you are.

And yet in most of Fassbinder's work, especially as he matured, there are moments of grace, and they can be overwhelmingly moving. The ending of

Fear Eats the Soul is probably the most obvious example of this, but that's mostly because it is at the end, and Fassbinder generally avoids putting grace there. Endings are, for him, usually the sites of annihilation or reckoning, moments for the audience to wonder how we got here, and what we must do to avoid such personal or social apocalypse. We might state one of Fassbinder's major themes as: "In a world set against you, a world that will eventually destroy you, how do you live so that, at the very least, you don't deserve to be destroyed?"

On June 10, 1982, thirty years ago today,

Rainer Werner Fassbinder died. He was among the most remarkable filmmakers of all time, a director whose work I've wrestled with and adored for a while. His extraordinarily rich, diverse, and vast

oeuvre has become the single body of film work that most fascinates me, though I still haven't been able to see it

all (few people have).

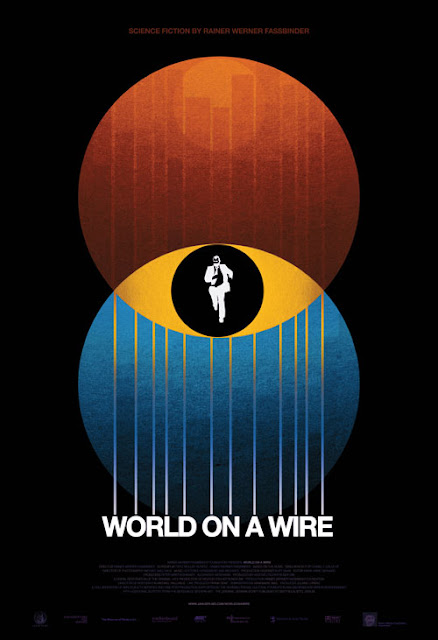

I've written a bit about Fassbinder, and specifically his astounding TV movie World on a Wire, previously, but I've resisted writing about him more, partly out of a sense of humility in the face of his accomplishments and partly because I still feel, even after years of watching his movies, very much a beginner as a Fassbinder viewer.

|

| Fear Eats the Soul (1974) |

But even with the acclaim Fassbinder has received and the esteem in which he is held by many cinephiles, his films seem to have trouble staying available to viewers — though roughly 75% of them have been released on DVD at one point or another in the US or UK, many of those editions have long gone out of print, and some, like the US DVD of

Effi Briest, now sell for quite a lot of money on the used market. (I am grateful to my past self, who bought it for a perfectly reasonable price when it came out in 2003.

The Arrow Films UK DVD is available, though.) Recently, Criterion's magnificent boxed set of

The BRD Trilogy went out of print, though Criterion has

reportedly said there will be a re-release at an unspecified time in the future.

I have decided to try to write a bit more about Fassbinder, then, to keep his name out there, to try to express some of what I find so affecting about his films, and, most importantly, to proselytize in his favor, with the hope that other people will do so as well, because it is only through proselytizing that more of his work may become, and remain, available to audiences worldwide. (If anybody out there wants to join me in writing about Fassbinder over the coming months, please feel free to put links to what you write in the comments here, or

email me.)

0 Comments on 30 Years After Fassbinder: Where to Begin? as of 1/1/1900

0 Comments on 30 Years After Fassbinder: Where to Begin? as of 1/1/1900

My latest column is up at Strange Horizons, and this time it's about Rainer Werner Fassbinder's epic science fiction film World on a Wire (Welt am Draht). If you want to see World on a Wire (and you should!), it's available on home video in the U.K. and Europe, and in the U.S. can be seen via Hulu if you subscribe to Hulu Plus (you can get a free trial subscription for a week, or if you have .edu email address, for a month). Rumor has it that Criterion will be releasing the film on DVD and Blu-ray in the U.S. at the end of this year or the beginning of next. It's also still touring various U.S. cities -- at the end of this week, it will be at the Harvard Film Archive in Cambridge, MA. I'm a Fassbinder nut, so will passionately defend even his films that only lunatics defend, but you don't have to be as obsessed with Fassbinder as I to see get pleasure from World on a Wire. (Although if "efficient" plotting, suspenseful storytelling, and "round" characterizations are your primary requirements for pleasure, you should probably stay away.) While World on a Wire isn't of the power and depth of, say, Berlin Alexanderplatz or a handful of Fassbinder's other absolute masterpieces, it's still a powerful, unsettling, beautiful movie, and the restoration that the Fassbinder Foundation did is remarkable -- to take an old 16mm master made for TV and turn it into something that can be admired on a giant cinema screen is no easy feat. I could go on and on. I won't. Instead, if you want a taste of the film, check out the trailer, which I'll embed after the jump here:

|

Coincidentally, a commercial Hollywood sf film (THE THIRTEENTH FLOOR)was later made (1999) based on the same obscure SF novel WORLD ON A WIRE is based on: SIMULACRON 3, by Daniel F. Galouye.

I've only seen a couple of Fassbinder's films--back in the 80s when a theater near me here in NYC was having a Fassbinder festival and a friend of mine who was a fan talked me into going. I can't say he made a convert of me. I can't recall the name of one of the films I saw, but the other was FOX AND HIS FRIENDS.

Finding your way into Fassbinder's work can be hugely challenging -- for years, I thought I hated him because I'd only seen The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant and Effi Briest, and found both cold, slow, boring. It wasn't until I saw Fear Eats the Soul and The Marriage of Maria Braun that I suddenly understood what all the fuss was about. And once I'd fallen in love with those two, I was able to go back to the others and see what I hadn't seen before. He's not a filmmaker whose work you can just randomly dip into; it really matters where you begin. (And he may still not appeal to you, of course. No art is universal.)

And yes, 13th Floor is from the same source, but as I note in the SH piece, it's actually not coincidental -- Fassbinder's cinematographer for World on a Wire, Michael Ballhaus, loved the story and once he had some clout in Hollywood he worked on getting it made. It's not a bad movie itself, really, but it's a pretty shallow one in comparison to World on a Wire, and vividly demonstrates, to me at least, what a really great director like Fassbinder can bring to a production (one that had a tiny budget in comparison).

Doh! I feel foolish that I didn't notice you had mentioned THE THIRTEENTH FLOOR in your article...and not just in passing. This is what comes from browsing rather than really reading what one assumes to comment on.

I saw THE THIRTEENTH FLOOR when it was released, but I can remember virtually nothing of it...a testament to its unimaginative blandness.

Maybe I'll try to see WORLD ON A WIRE...it may even still be playing here in NYC.