And what is the best way to ensure an easy transition for offenders that are about to be released? Julian Roberts, author of Criminal Justice: A Very Short Introduction, tells us the top 10 things everyone should know about criminal justice, and what the chances and limitations of the Western system are.

The post 10 interesting facts about criminal justice appeared first on OUPblog.

Ever wanted to change a behavior or habit in your own life? Most of us have tried. And failed. Or, we made modest gains at best. Here’s my story of a small change that made a big difference. Just over two years ago, I decided, at the ripe old age of 55, that it was time to begin exercising.

The post It’s never too late to change appeared first on OUPblog.

By David Skarbek

On 11 April 2013, inmate Calvin Lee stabbed and beat inmate Javaughn Young to death in a Maryland prison. They were both members of the Bloods, a notorious gang active in the facility. The day before Lee killed Young, Young and an accomplice had stabbed Lee three times in the head and neck. They did so because Lee refused to accept the punishment that his gang ordered against him for breaking “gang rules.” Lee didn’t report his injuries to officials. Instead, he waited until the next day and killed Young in retribution.

While this might seem to provide evidence that gangs are inherently violent, that’s not so. The story is more complicated. Gangs enforce a variety of rules that they design to establish order. Lee violated these rules by giving his cellmate—who had a dispute with a rival gang—a knife. Many inmates would see this as encouraging violence, which gangs seek to control. The situation provides a glimpse at a major role played by prison gangs. They don’t form to promote chaos, but to limit spontaneous acts of violence.

Many people are surprised to learn about the extent to which gangs regulate inmate life. Not only do many inmates feel they must join a gang, but gangs even issue written rules about appropriate social conduct. These include who you may eat lunch with, which shower to use, who may cut your hair, and where and when violence is acceptable. One gang gives new inmates a written list of 28 rules to follow. Many gangs even require new inmates to provide a letter of introduction from gang members at other prisons. Moreover, gangs also encourage cooperation within their group by relying on elaborate written constitutions. These often include elections, checks and balances, and impeachment procedures.

Besides setting rules, prison gangs promote social order by adjudicating conflict. Inmates can’t turn to officials to provide this when dealing in illicit goods and services. An inmate can’t rely on a prison warden to resolve a dispute over the quantity or quality of heroin. They can’t turn to officials if someone steals their marijuana stash.

In short, prison gangs form to provide extralegal governance. They enforce property rights and promote trade when formal governance mechanisms don’t. The provide law for the outlaws.

Yet, gangs’ dominance today stands in stark contrast with the historical record. In California, the prison system existed for more than a century before prison gangs emerged. If gangs are so important today, then why didn’t they exist for more than 100 years?

A major cause of the growth of prison gangs is the unprecedented growth in the prison population in the last 40 years. The United States locks up a larger number and proportion of its residents than any other country. This amounts to about 2.2 million people (707 out of every 100,000 residents). With such large prison populations, officials can’t provide all the governance that inmates’ desire. Mass incarceration thus creates fertile conditions for the rise of organized prison gangs.

David Skarbek is a Lecturer in the Department of Political Economy at King’s College London. He is the author of The Social Order of the Underworld: How Prison Gangs Govern the American Penal System, which is available on Oxford Scholarship Online. Read the introductory chapter ‘Governance Institutions and the Prison Community’ for free for a limited time.

Oxford Scholarship Online (OSO) is a vast and rapidly-expanding research library, and has grown to be one of the leading academic research resources in the world. Oxford Scholarship Online offers full-text access to scholarly works from key disciplines in the humanities, social sciences, science, medicine, and law, providing quick and easy access to award-winning Oxford University Press scholarship.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only social sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Why do prison gangs exist? appeared first on OUPblog.

‘Honor killings’ consistently make the headlines, from a Brooklyn cab driver convicted of conspiracy to a recent decapitation in Pakistan. However, it’s become increasingly difficult to sort fact from fiction in these cases. We asked Rosemary Gartner and Bill McCarthy, editors of The Oxford Handbook on Gender, Sex, and Crime, to pull together an essential grounding for this muddled subject matter. Here they’ve adapted some information from “Honor Killings” by Dietrich Oberwittler and Julia Kasselt (Chapter 33).

(1) Honor killings are an extreme form of gendered domestic violence. Most involve young, single female victims and an assailant who is a male relative; however, they also include some types of intimate-partner homicides, as well as cases with male victims, victims outside the family, and female assailants. An honor killing is motivated by the desire to restore a social reputation that—in the killer’s perception—has been damaged by rumors about or the victim’s actual breach of conduct norms regulating female sexuality in the widest sense; the decision to use lethal violence is a collective family affair, rather than the action of an individual perpetrator. The underlying motive in all cases—irrespective of the victims’ gender—is the punishment or coercion of women.

(2) The absence of reliable country-level data makes it impossible to ascertain the exact frequency of honor killings; recent estimates suggest that there may be as many as 5000 per year. Countries with reported high rates of honor killings score poorly in the international Human Development Index and the Gender Inequality Index and rank highly in the Failed State Index.

(2) The absence of reliable country-level data makes it impossible to ascertain the exact frequency of honor killings; recent estimates suggest that there may be as many as 5000 per year. Countries with reported high rates of honor killings score poorly in the international Human Development Index and the Gender Inequality Index and rank highly in the Failed State Index.

(3) It is likely that the majority of perceived transgressions of honor do not provoke a murder. Research in a number of countries with people who differ in their religious affiliations finds that premarital sexual relationships and out-of-wedlock pregnancies often are dealt with nonviolently, mostly by negotiating compensation or marriage, despite strict honor codes.

(4) Islam plays a prominent role in public debates on honor killings, yet honor killings are a pre-Islamic tribal tradition and an extra-judicial punishment that is not part of Sharia law. Honor killings occur among Christian minorities in Arab countries, as well as among the Sikh community in India (and among their respective immigrant communities in the West). They appear to be non-existent in some Muslim-dominate countries, such as Oman, and less frequent in others, such as Algeria and Tunisia. Nonetheless, some interpretations of Islamic law, such as those that promote the lawfulness of husbands’ physical violence against wives, the criminalization of pre- and extramarital sexual relationships, and the use of flogging or stoning if prosecuted as hadd (religious) crimes (which does not happen in most Muslim countries), may contribute indirectly to honor killings.

(5) Findings from the World Values Survey highlight a notable split of orientations in many countries with high levels of honor killings: Democratic political values are commonly endorsed, but public opinion remains much more conservative when it comes to gender equality and sexual liberalization, with almost no trend toward more liberal views among younger age groups.

Dietrich Oberwittler and Julia Kasselt are the authors of “Honor Killings” in Chapter 33 of The Oxford Handbook of Gender, Sex, and Crime. Dietrich Oberwittler is a senior researcher in sociology at the University of Freiburg and Max Planck Institute for Foreign and International Criminal Law. Julia Kasselt is a Ph.D. candidate at the Max Planck Institute for Foreign and International Criminal Law. Rosemary Gartner and Bill McCarthy are the editors of The Oxford Handbook of Gender, Sex, and Crime. Rosemary Gartner is Professor of Criminology and Sociology at the Centre for Criminology and Sociolegal Studies at the University of Toronto. She is the co-author of three books: Violence and Crime in Cross-National Perspective (Yale, 1984), Murdering Holiness: The Trials of Edmund Creffield and George Mitchell (University of British Columbia Press, 2003) and Marking Time in the Golden State: Women’s Imprisonment in California (Cambridge, 2005). Bill McCarthy is Professor of Sociology at the University of California Davis. He is the co-author (with John Hagan) of Mean Streets: Youth Crime and Homelessness (Cambridge, 1997).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only social sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Abandoned child’s shoe on balcony with diffuse filter. © sil63 via iStockphoto.

The post Five important facts about honor killings appeared first on OUPblog.

By Pippa Holloway

Nearly six million Americans are prohibited from voting in the United States today due to felony convictions. Six states stand out: Alabama, Florida, Kentucky, Mississippi, Tennessee, and Virginia. These six states disfranchise seven percent of the total adult population – compared to two and a half percent nationwide. African Americans are particularly affected in these states. In Florida, Kentucky, and Virginia more than one in five African Americans is disfranchised. The other three are not far behind. Not only do individuals lose voting rights when they are incarcerated, on probation, or paroled, a common practice in many states, but some or all ex-felons are barred from voting. All six of these states have non-automatic restoration processes that make it difficult or impossible to have one’s rights restored. Not coincidentally, all of these states maintained a system of racial slavery until the Civil War.

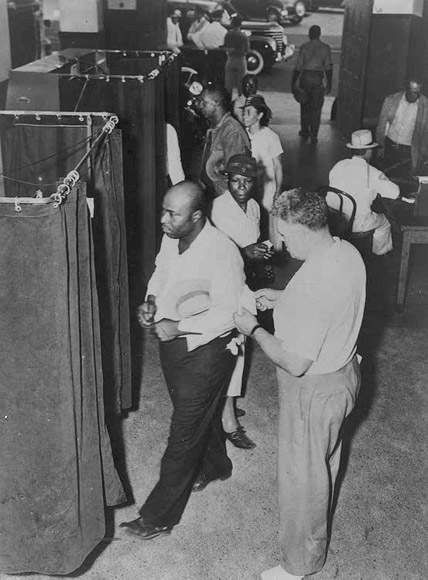

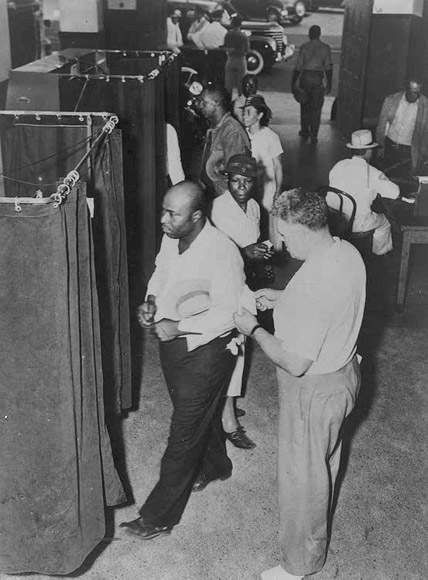

Voters at the Voting Booths. ca. 1945. NAACP Collection, The African American Odyssey: A Quest for Full Citizenship, Library of Congress. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

At the other end of the spectrum are northeastern states, mostly those in New England, which put up few obstacles to voting by convicted individuals. Maine and Vermont are the only states in the nation that do not disfranchise anyone for a crime, even individuals who are incarcerated. Among the remaining 48 states, Massachusetts and New Hampshire disfranchise the smallest percentage of convicted individuals. Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Pennsylvania are also far below the national average.

Generalizations about regional difference are complex should be made cautiously. Although the six states with the highest rates of disfranchisement are all in the South, six other states also impose life-long disfranchisement for some or all felons. Arizona and Nevada have relatively high rates of felon disfranchisement. Midwestern states, particularly Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, and Michigan, have low rates of felon disfranchisement, as does North Dakota. Nonetheless, the Northeast and South stand in stark contrast.

Regional differences in felon disfranchisement today are the result of regionally divergent histories of slavery and criminal justice. New England states had outlawed slavery by 1800. Soon, they also stopped treating convicts like slaves, barring state-administered corporal punishment for criminal offenses in the first few decades of the nineteenth century. Instead, northeastern states embraced an ideology of criminality that emphasized rehabilitation. This attitude toward both slavery and punishment led many citizens and lawmakers in the northeast to oppose disfranchisement of convicts or at least curb the reach of this punishment. In the colonial era, Connecticut limited the courts that could deny convicts the vote. Maine’s 1819 constitutional convention rejected a proposal to disfranchise for crime. Vermont ended the practice in 1832. In other northeastern states proponents of such disfranchisement measures faced strong opposition. For example, Pennsylvania’s 1873 constitutional convention restricted felon disfranchisement to those convicted of election-related crimes; an effort to disfranchise convicts in Maryland in 1864 passed only after a long debate.

In contrast in the nineteenth-century South two groups were permanently cast out of full citizenship: African Americans and convicts. Although the enslavement of African Americans ended in 1865, “infamy” – the legal status of those convicted of serious crimes – was imposed on a growing number of the new black citizens. Accusations of prior crimes were used in the 1866 election as one of the first tools used to deny the vote to former slaves. In the 1870s, nearly every state in the former Confederacy (Texas being the exception) modified its laws to disfranchise for petty theft, a move celebrated by white leaders as a step toward disfranchising African Americans.

The legacy of slavery and segregation in the South is important to this story but so is the different regional trajectory of criminal justice. All southern states except South Carolina and Georgia (states today that still have among the lowest rates of disfranchisement in the South) enacted laws disfranchising for crime between 1812 and 1838, and there is little evidence of dissent or debate over this punishment anywhere in the region. Furthermore, southern states rejected the concept of criminal rehabilitation and focused instead on punishment. After the Civil War “convict lease” systems replicated in many ways the system of slavery for those who fell into it, creating a class of mostly-black individuals who were subject to physical punishment, public abuse, and humiliation, and denied voting rights.

In the past, as is also true today, individuals with criminal convictions fought long battles to regain their voting rights. Far from being a population that is uninterested in politics, individuals barred from voting have challenged obstacles to re-enfranchisement and overcome tremendous hurdles to have their voting rights restored. Consider the case of Jefferson Ratliff, an African American farmer living in Anson County, North Carolina, who in 1887 paid the court an astounding $14 to have his citizenship rights restored, ten years after his conviction for larceny (including three years’ incarceration) for stealing a hog. In Giles County, Tennessee in 1888 a man named Henry Murray paid $2.70 in court costs in an unsuccessful effort to have his voting rights restored. In other cases, poor and illiterate individual petitioners facing a complicated legal process sought help from friends and neighbors. In Georgia, Lewis Price petitioned Governor William Y. Atkinson in 1895 for a pardon so that he could vote. He explained, “I am a poor ignorant negro and I have no money to pay to the lawyers to work for me. So I have to depend on my friends to do all of my writing.”

The historical record shows that state and local governments have consistently failed, throughout the nation’s history, to enforce these laws in a fair and uniform way. Coordinating voter registration lists with criminal court records and pardon records — difficult in today’s world of information technology — was nearly impossible in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. People who should have been able to vote were often denied the vote due to false allegations of disfranchising offenses; convictions were secured through suspect judicial processes prior to an election for partisan ends; and people who should have been disfranchised often voted. Sometimes these appear to have been honest mistakes made by officials charged with merging complicated statutory and constitutional requirements with voter registration data and court records. In many cases though, other agendas—partisan, racial, personal—seem to have been at work. In short, felon disfranchisement laws have long been subject to error and abuse.

Race both rationalized and motivated laws imposing lifelong disfranchisement for certain criminal acts in the post-Civil War period. Since then a variety of factors have led to the persistent sense, particularly in southern states, that individuals with prior criminal convictions are marked with a disgrace and contamination that is incompatible with full citizenship. Felon disfranchisement today preserves slavery’s racial legacy by producing a class of individuals who are excluded from suffrage, disproportionately impoverished, members of racial and ethnic minorities, and often subject to labor for below-market wages. In these six southern states, the ballot box is just as out of reach for former convicts as it was for enslaved African Americans two centuries ago.

Dr. Pippa Holloway is the author of Living in Infamy: Felon Disfranchisement and the History of American Citizenship, published Oxford University Press in December 2012. She is Professor of History at Middle Tennessee State University. Contemporary data comes from Christopher Uggen, Sara Shannon, Jeff Manza, “State-Level Estimates of Felon Disenfranchisement in the United States, 2010.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Felon disfranchisement preserves slavery’s legacy appeared first on OUPblog.

By Susan Easton

In the wake of the recent riots, much attention has been given to the causes of the riots but an issue now at the forefront of press and public concern is the level of punishment being meted out to those convicted of riot-related offences. Reports of first offenders being convicted and imprisoned for thefts of items of small value have raised questions about the purposes of sentencing, the problems of giving exemplary sentences and of inconsistency, as well as the issue of political pressure on sentencers.

(2) The absence of reliable country-level data makes it impossible to ascertain the exact frequency of honor killings; recent estimates suggest that there may be as many as 5000 per year. Countries with reported high rates of honor killings score poorly in the international Human Development Index and the Gender Inequality Index and rank highly in the Failed State Index.

(2) The absence of reliable country-level data makes it impossible to ascertain the exact frequency of honor killings; recent estimates suggest that there may be as many as 5000 per year. Countries with reported high rates of honor killings score poorly in the international Human Development Index and the Gender Inequality Index and rank highly in the Failed State Index.