new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: catherine butler, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 16 of 16

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: catherine butler in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

Many children’s writers find giving their book a title one of the trickiest parts of the job. It’s an important consideration, though: along with the jacket design and the name of the author, the title of a book is the thing mostly likely to make a potential reader pluck it from the shelf or leave it be. But what strategy works best? Direct or oblique? Short or long?

There is no single answer: both Joan Aiken’s

Is and Russell Hoban’s

How Tom Beat Captain Najork and His Hired Sportsmen strike me as excellent, though they have little in common. (Aiken’s of course would give a present-day marketing department conniptions, being virtually invisible to search engines, but that’s a different matter.) Back in 1950, when my mother was a humble secretary at Geoffrey Bles, C. S. Lewis sent them a manuscript called

The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, with a note to the effect that this was obviously just a working title - and it was only at Bles’s persuasion that he used it for the published book. History has proved Bles right, but I can see Lewis’s point too: it

does look like a working title, once you allow for the beer goggles of hindsight.

Titles have their fashions, like anything else. For example, the big Disney blockbusters of recent years have mostly been past participles:

Enchanted,

Frozen,

Tangled (or “Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered,” as I like to think of them). This snappy style is seen as more in keeping with the busy lifestyles and short attention spans of modern children, but it’s a sobering thought that if

Sleeping Beauty and

Cinderella had been made today they would have been called

Prickedand

Slippered.

Around the turn of the millennium there was a vogue in Young Adult fiction for titles that described continuing actions or progressive states, in the form “Verb + ing + Noun”: Gathering Blue, Burning Issy, Missing May and so on. I suppose this was intended to evoke a sense of adolescence as a moving target, a time of change and flux. Any device can be overused, however, and when I wrote Calypso Dreaming (2002) I deliberately reversed the order so as to make my book stand out. How well that strategy worked in terms of sales I leave to historians to record.

If you want to make your own YA title from circa 2000, you can do it by following these simple steps. Turn to page 52 of the book nearest to you and find the first transitive verb; add “ing” to it, and then the name of your first pet. Voilà – there’s your title! (I got Vexing Topsy.)

Alternatively, perhaps you wish to produce a prize-winning children’s novel from the sixties or early seventies? In that case it pays to give it a title in the form:

“The + Slightly-Quirky-Noun-Used-as-Adjective + Noun”

This will confer the air of poignant obliquity so appealing to publishers of that era, home to such books as

The Dolphin Crossing,

The Owl Service,

The Chocolate War and

The Peppermint Pig. Naturally the success of this strategy depends a little on one’s choice of words, so to make it easier I invite you to use the chart below, which contains a selection of words approved by our experts as Puffin-friendly. Simply look for the month and day of your birth to find your own title. There are 84 possible combinations, any of which would, I’m sure, have been a shoo-in for the Carnegie shortlist and warmly recommended by Kaye Webb as “a thoughtful novel about growing up that will appeal to slightly older girls.”

Mine’s The Blue Moon Promise. What’s yours?

It’s a strange thing about the literature of the First World War. We can all probably name some of the writers that conflict brought to fame: Wilfred Owen, Siegfried Sassoon, Isaac Rosenberg, Edward Thomas, Rupert Brooke and the rest. All of them soldiers, many of them dead by November 1918. And all poets, of course. But where are the great prose works of the Great War? The first ones that spring to my mind at least are Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front (1929), Robert Graves’s Goodbye to All That (1929), Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms(1929) and Vera Brittain’s Testament of Youth (1933). All, note, published a decade or more after the Armistice. It seems strange, doesn’t it, that – contrary to Wordsworth’s dictum about poetry being “emotion recollected in tranquility” – it was the poetry that was written during the event, and the prose so much later?

I’m aware, of course, that all this is a large and woolly generalization. Some important First World War poetry was written long after the event, such as David Jones’s In Parenthesis (1937); and of course there were novels and short stories prior to 1929; but the names I’ve mentioned are the ones that seem to have lasted. It’s as if prose authors’ experience of the war needed time to settle into a form in which they felt sufficiently sure of themselves and their own feelings to set it down. A period of quarantine, as it were.

This train of thought was started by a question that cropped up while I was writing a piece about female children’s authors in the decades after 1945. I knew (and more-knowledgeable friends have since confirmed) that during the Second World War itself there had been numerous children’s books with a contemporary wartime setting. Elinor Brent-Dyer’s Chalet School fled first from Nazi-held Austria to Guernsey and thence to Britain during the war years. Biggles took on Hitler’s airmen just as he had the Kaiser’s. William Brown encountered air raids and evacuees, and even The Beanointroduced wartime characters (most infamously Musso da Wop – He's a Big-a-da-Flop). But, as with the First World War, once VJ day passed the well of wartime fiction dried up. A couple of books with wartime settings appeared in 1946, including Noel Streatfeild’s Party Frock, about a girl who is sent a beautiful frock from America but has no chance to wear it because of the general austerity; but I suspect these were already being written before peace was declared. After that there’s very little, at least from British writers. True, in 1956 The Silver Sword, Ian Serraillier’s classic story of European refugees, was published; and around the turn of the 1960s boys’ comics like War Picture Library and The Victor started featuring stories from the Second World War on a regular basis, with Germans who could be relied on to shout things like ‘Achtung, Schweinhund!’ and ‘Hände hoch!’. (Such comics were of course primarily read by children with no personal memory of the war itself.) However, I’m not aware of any Second World War children’s novel by a female British author being published in the twenty years after 1946 – which seems remarkable, if true (and please let me know if it’s not).

Finally, in the late sixties and early seventies, those authors who had been children during the war began to produce their own novels, mostly about the Home Front. There are lots of these, many of them excellent. Some of the best are Jill Paton Walsh’s Fireweed(1969), Susan Cooper’s Dawn of Fear(1970), Jane Gardam’s A Long Way from Verona (1971), Judith Kerr’s When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit (1971), Nina Bawden’s Carrie’s War (1973), Robert Westall’s The Machine-Gunners (1975) and Alan Garner’s Tom Fobble’s Day (1977). Like the books by Hemingway, Graves and Brittain, many are autobiographical or semi-autobiographical in nature.

Looking at this very brief and even more unscientific survey of the literature of the two world wars, I’m struck as much by the absences as by the books themselves – by the fact that such cataclysmic events apparently cannot be turned immediately into fiction, whether because to do so would in some way trivialize the suffering (but why should that be?), or because they were too overwhelming and all-encompassing to submit to the peculiar discipline art demands – to the filtering, the selection, the transmutation of chaotic real-world experience into some kind of half-confabulated order. And what is true of wars is likely true of other traumas, too. We write of them only when we can, which may be decades after the event. That’s why some of us, I’d guess, become children’s writers. To bear our own belated witness.

Most people would agree that talent and hard work are both important ingredients in any artistic or sporting career, and indeed in many other endeavours. But which is more important? And which is more to be admired?

It’s a difficult thing to measure, but my impression is that in British culture there’s been a gradual shift in emphasis over my lifetime, from talent to hard work. For example, in the early 1970s my favourite tennis player was Ilie Năstase, and the main reason I liked him was that his play was so beautiful and imaginative. It didn’t matter that he never won Wimbledon – that was part of what made him rakishly attractive, like a top button left artfully undone. Then, around 1974, I was surprised to hear another player grunt loudly and effortfully as he hit the ball. The grunter was Jimmy Connors, a hardworking but unlovely player, who did win Wimbledon, twice. (Both were soon to be eclipsed by Swedish Jesus-lookalike Bjorn Borg, who successfully combined grace and power.) Connors’s grunts were unfavourably received by old-school BBC commentators such as Dan Maskell, ostensibly because they had the potential to distract his opponents, but I think the real reason was that it made his play look altogether too much like hard work. No doubt Borg and Năstase practised, but they did it out of sight: their performances were cool iceberg tips, never mind what lay below the surface. Today, by contrast, all sportspeople are expected to give 110% as a bare minimum, and Andy Murray’s matches, for all their skill, frequently recall

the boxing scene in Cool Hand Luke. If you’re not visibly suffering, you don't deserve to win.

Amongst writers too hard work is admired, but it's also very slightly suspect. We may praise Anthony Trollope for getting up at 5.30am each morning and writing 3,000 words before leaving for his day’s work at the Post Office (if he finished a novel before 8.30 he would take a fresh sheet of paper and start on the next); but our admiration is not unmitigated: his routine sounds anything but inspiring or inspired.

In The Courtier (1528) Baldassare Castiglione coined the useful term sprezzatura to denote the seemingly effortless skill with which a courtier should be able to ride, fence, dance, play an instrument, and so on. Its employment as a positive description is interesting, for the word comes from the Italian for “contempt” or “negligence”, qualities we don't normally admire. But aren't masters of sprezzatura merely con merchants, working feverishly behind the scenes to acquire the skills they pretend to have naturally?

More fundamentally, why should we praise people for having talent in the first place? While some people certainly have more natural ability than others (no matter how hard I train I will never be able to run as fast as Usain Bolt), surely being given a head start by your DNA doesn't make you praiseworthy, any more than winning the lottery or inheriting a business empire makes you a hardworking entrepreneur. Anyway, why would we want to look like someone who’s never had to try? Aren't the admirable people the ones who do a lot with the resources they have?

I suspect that somewhere at the back of all this there’s a need to feel that some people are simply special, touched by the gods, and that the ease with which they produce great work is a measure of that specialness. Hence Heminge and Condell's compliment to Shakespeare on producing great plays while seldom blotting a line. It feels good to know that such people exist, even if they aren't us.

It's true that the subjective experience of writers is often that the best lines, the best ideas, appear to fall fully-formed into one’s lap, without apparent effort. However, remember the anecdote about the consultant who fixed a problem in a factory by turning a single lever – the work of a moment – and charged a £1,000 fee. When the factory owner questioned a bill of £1,000 for a moment’s work, the consultant replied that the fee was for the decades of experience and training that meant she could fix the problem in a moment. Perhaps it’s like that for writers: those “free” inspirations have actually been earned through years of grunt and grind.

Or, as a golfer once famously put it, “The more I practise, the luckier I get.”

Not Kismet House

Seen from the motorway, the headquarters of Kismet Enterprises appear almost deliberately anonymous. Situated outside Telford, just off the M54 and with a distant view of the Wrekin, it is a large building, with a pleasant fountain in front of the main entrance; but few of the travellers rushing between Birmingham and Shrewsbury are likely to give its nineteenth-century sandstone façade a second glance. And that seems appropriate, given the nature of the business conducted within. Many stories feature a Chosen One or an ancient prophecy, after all, but how often do readers stop to wonder who does the Choosing? Or where those ancient but invariably accurate prophetic verses actually come from? In most cases, the answer lies here in Kismet House.

Kismet’s operations are usually hidden from public view, but today I have been given exclusive access to one of their most senior employees. Mrs Lachesis Webster’s title is displayed in brass letters on her office door: Head of Choosing.

Mrs Webster does not stand on ceremony. She opens the door to her office before I have a chance to knock, greeting me warmly. She is a small woman of indeterminate age, greying but smooth-skinned, careful in her movements as in her words. The office is handsomely appointed, with luxurious armchairs and original oil paintings, but nothing here is new: the carpet shows signs of wear where she has made her way between door and desk, every day for the last twenty-five years.

Mrs Webster gestures to me to sit, and lands rather heavily in her own chair. Although she smiles, behind her half-moon spectacles I sense a great weariness.

I take out my pen and notebook.

“Thank you for agreeing to talk with me. I’m sure our readers will be fascinated to hear about your work.”

She nods acknowledgement. “We don’t get many visitors in this part of the building. I’m happy to oblige.”

“It’s quite a warren! To be honest, I hadn’t realised how big a bureaucracy was involved in allotting fates.”

Mrs Webster looks a little surprised. “I think people underestimate the level of detail required. When I first came here I spent six months just working on umbrellas!”

“Umbrellas! Really?”

“I was assigned to the Fortune Assessment section at the time, a rather technical department. Everyone knows that it’s unlucky to open umbrellas indoors, of course. But what about opening them on a covered porch? Under an awning? In a bus shelter? Is that bad luck too?”

“I couldn't say.”

“Is an overhead covering the crucial factor, or is it being open to the elements? And then of course there are verandahs! Gazebos! Pergolas!”

“Pergolas? Is he some relation to Legol—?”

“It all has to be worked out and negotiated, painstakingly. Nothing is left to chance. Endless reports, meetings, protocols, guidelines…” Her eyes, briefly aflame, dim until they are but pilot lights. “It was all a bit much, to be honest. Not that I blame them for being careful. Of course it’s even worse in the Wishes Division.”

“But surely wishes are just—” My sentence stutters on the word “lovely”.

“Ah, you’re too young to remember the great Recursive Wish Crisis of 1962. A spike in people wishing for more wishes almost caused a chain reaction, a runaway escalation of contradictory magics that threatened to destroy – well, everything. Since then, all wishes have had to be signed off in triplicate. I’ve never met a more joyless, dour lot than the wish granters of today. The romance has gone out of it.”

“You never worked in that area yourself?”

“No, no. As soon as I’d served my probationary period I applied for a transfer out of Fortune Assessment. I spent a couple of years in the South Wing, first in Portents, and then next door in Prophecy and Augury.”

“That sounds fascinating! Tell me something about your work there.”

“Oh, well there’s always a demand for prophecies, isn’t there? You know, to underwrite events? Prophecies are such a convenient glue if you don’t have time to make dovetail joints. I wasn’t allowed to do the big, complex ones with multiple stanzas, of course. I specialized in couplets.”

“Might you share an example of your work?”

“Let me think… I believe the very first prophecy I came up with was this:

When Maxen wears the royal ring

It means that he is now the king.”

“That’s very… straightforward.”

She sighs. “I know – especially since Maxen was Crown Prince at the time. Prophesying what everyone expects to happen anyway was one of my weaknesses.” She laughs at my expression. “It’s all right, I know it’s awful, you needn’t be diplomatic. They weren’t diplomatic in Prophecy and Augury! I remember my boss at the time shouting: ‘Ambiguity, ambiguity, ambiguity!’ That was his constant watchword, you see. ‘Lachesis,’ he used to tell me, ‘We don’t make prophecies to tell people what the future’s going to be, we make them so they’ll recognize the future once they’ve arrived there!’ Wise words, you’ll agree. Oh, I learned a lot at P&A.”

“And yet you moved on?”

“I made some good friends – I’ve never known such a bunch for practical jokes! But I just didn’t have the flair, you see. I’m too straightforward. Of course, as the Choosing One I still work very closely with my colleagues in P&A. We have to coordinate.”

“So let’s talk about your current position. What are the principles on which you do your choosing? Are you a birther?”

“I don’t much care for that term, though I know it’s become entrenched. As a matter of fact, when I first started in the post I assumed that in this more democratic age Chosen Ones would normally be selected on worth rather than birth. I thought the ideal was to find an obscure young man or woman who was goodhearted, brave, and underappreciated – preferably located at several adventures' distance from the capital city.

That was my idea of good Chosen One material. Birth wasn’t a consideration. In recent years, however, there’s been a renewed demand for heroes and heroines of exalted parentage. They can be brought up as obscurely as you like, but people want them to turn out to be the children of royalty or gods – or wizards at the very least. We’ve had to dust off whole shelves of superannuated material on birthmarks, lisps, scars, and suchlike methods of identifying Lost Heirs. (Oddly, the field seems oblivious to the science of DNA.) It’s a step backwards, really. I blame Disney.” Mrs Webster sighs deeply.“You preferred the old times, then?”

Suddenly she looks her age. Gazing at her weary face I have the impression of a private school headmistress who’s just returned from a walking tour of Mordor and is about to write a stinging review on Tripadvisor.

“Old people do, don’t they?” she remarks. “It’s our defining folly. Besides, I still do things my way most of the time."

“So, what is the actual process? How do you find a name for your Chosen One?”

She looks at me steadily. “That would be telling, Ms Butler.”

Mrs Webster has another appointment looming, so I must take my leave. We shake hands, and I thank her for her time. The heavy door of her office closes behind me.

But I am not an investigative reporter for nothing. Slipping to the back of the building, I count along the mullioned windows and find the one that opens onto Mrs Webster’s office. Peering in between the ivy trails, I see her hunched at her desk just a yard of two beyond the glass, a mighty ledger open before her. A telephone directory? No, this surely is the Book of Life, I tell myself. This is how the Chosen Ones are chosen! And I’m about to witness it at first hand.

Mrs Webster covers her eyes with one hand and riffles through the pages, apparently at random. Then, with the other hand she takes a large steel pin from the desk – and stabs it blindly into the paper.

Somewhere, a child is crying.

Somewhere, a Chosen One is born.

There’s an old piano and they play it hot

Behind the green door,

Don't know what they’re doin’ but they laugh a lot

Behind the green door,

Wish they’d let me in so I could find out what’s

Behind the green door.

So sang Jim Lowe in 1956, in a song that epitomizes the experience of the excluded, of the Outs who wish they were In. It’s a universal aspect of the human condition, no doubt, this feeling that someone else is having a better time than you, and that if you could just get beyond the Green Door – whatever form it takes – then your happiness would be complete. Writers experience it quite starkly, for every published writer was once an unpublished writer, pressing his or her nose up against the glass and pining for recognition; but human discontent assumes many shapes. C. S. Lewis wrote a very insightful essay on this subject called “The Inner Ring”, and if you only have time to read either this post or that essay, I recommend you choose the latter.

Well then; last Sunday I went to the Cheltenham Literary Festival to take part in an author session. It was only my second visit to the Festival – to my shame, for it’s less than 50 miles from Bristol, an easy trip up the M5 or by direct train. But small efforts can be more daunting than big ones, as you know.

My first visit was a few years ago, to hear Alan Garner. On that occasion I was very much a fan, standing happily in the signing queue with my copies of The Owl Service and Elidor. In fact I found myself next to another author in the shape of both halves of Tobias Druitt. Garner’s a writer’s writer, I think, so meeting other authors there was not surprising, but because he signs in a careful calligraphic script his queues move slowly. There was plenty of time to chat.

Last Sunday was different. This time I was a stand-in for Ursula Jones, who was herself a stand-in for her sister Diana Wynne Jones. When Diana died in 2011 she left a not-quite-finished novel, The Islands of Chaldea, which Ursula was asked by the family to conclude – and conclude it she did, quite masterfully in my opinion. The plan had been for Ursula to do an event “in conversation” with the Australian fantasy writer Garth Nix, who’s on tour promoting his excellent new book Clariel, but unfortunately she had to pull out at short notice. I was suggested as a replacement, since I know Diana’s work well and had been consulted about The Islands of Chaldea in the early stages.

The event was a success: Garth Nix is a fascinating and funny speaker, and Julia Eccleshare made an excellent host. I hope the audience weren’t too disappointed at having me there rather than Ursula, but if they were they hid it well. But that’s not what this post is about. It’s about the Authors’ Tent (otherwise known as the Green Room), where speakers at the various events are able to relax and take refreshment. I’ve been in Green Rooms before, at fantasy conventions and the like, and have helped myself to coffee and trail mix by the bucket, but none has been quite as prestigious or luxuriously appointed as the pleasure dome decreed by the powers that be in Cheltenham. (I am as yet a stranger to the Edinburgh Festival's fabled Authors’ Yurt, though in my personal mythology it’s on a par with Arthur’s Seat.)

Unfortunately I wasn’t able to spend much time in Cheltenham's Authors' Tent, and since I was driving I was unable to indulge in the free beer and wine, but I did stop for a few minutes to eat a scone and take in the scene around me. Writers sat here and there, chatting merrily. Some I recognized, some I felt I ought to recognize, but all looked entirely comfortable – and who wouldn’t, in a setting that was in itself a comforting reassurance that, “Yes, you have arrived”? In one corner a crèche of authorial children frolicked, and everywhere the tireless employees of the Festival served, cleared up, replenished and gave a general masterclass in the anticipation of whims. They were all fantastically cheery and helpful. They were so helpful, in fact, that I began to feel a little suspicious. Could they really be that anxious for my happiness? Anyone who’s spent as much time as I have pondering “Hansel and Gretel” knows that there’s no such thing as a free lunch. Might the scone be drugged? Would I wake to find myself chained to a gang of midlist authors in one of GCHQ's notorious data mines?

But no such calamity ensued. “Ooh, a bowl of miniature chocolate bars!” I exclaimed as I was getting ready to leave. “May I take one?” They were Green & Black, after all. “Take several!” they exclaimed. “We’re so grateful you were able to come!” Though I peered closely, I could detect no trace of irony in their expressions. They really seemed to mean it.

I was delighted with my visit, brief though it was, and my temporary access to the Inner Ring of lionized authors. Except that, just as I was leaving, I caught sight of another door – I could have sworn it was green – slightly removed from the main crush of the Authors’ Tent. Approaching it, I was turned brusquely away by an unsmiling guard: “Man Booker Winners only,” he informed me. With a sigh I set off back to Bristol, but not before I had briefly glimpsed the scene within through the green door’s tinted glass. And now, when I sleep, my dreams are haunted by the memory of Ian McEwan, Salman Rushdie and Hilary Mantel splashing in their exclusive Booker Winners’ hot tub, chinking complimentary champagne flutes, and laughing, laughing, laughing…

“If you write, why do you write?” a friend asked on Facebook yesterday.

It’s a good question, and of course there are many answers. I found some bubbling to the top of my brain almost immediately, but not all were very convincing. (“Because I have an important message for the world that it desperately needs to hear,” yes I’m looking at you. Nor, on reflection, do I really find the idea of wearing black polo-neck sweaters in a Greenwich Village loft apartment that attractive.)

Here are the ones that made the cut. Please note that no other reasons for writing are valid, aside from those given below. (But disagree, if you must, in the comments.)

- For the money [cue hollow laugh here]. Or at least for the ever-receding prospect of living by my

pen mouse. It could happen – right? - Because I have a story that seems to want telling, and it keeps hammering at my brainpan like a drunk trying to get into a late-night hostel.

- Because I like to see my name printed on the spines of books in bookshops. And in my house. And in other people’s houses. And on billboards, TV screens, cinema posters…

- A shed of one’s one.

- The technical aspects of writing a story are absorbing and satisfying, equally engaging of the heart, mind and spirit.

- Because I combine an inexhaustible interest in other human beings with a wish to spend large parts of every day out of their company.

- As a way to cheat death. I like to imagine that something of myself will survive me, and particularly that my descendants feel some personal connection beyond a name and dates.

- Like C. S. Lewis, I write the kinds of book I would like to read, and want to make sure there are more of them.

- Because there aren’t many jobs where strangers come up and tell you they admire you, and even ask for your autograph. Not that this happens to me very often, but it seems odd that writers should get this kind of treatment, when useful people like plumbers and brain surgeons generally don’t.

- It’s a habit – quite possibly a bad one.

- I’m rubbish at drawing and can’t dance, so writing (along with descant recorder) is my only outlet for self-expression.

- Because the profound satisfaction of having produced a successful story marginally outweighs the profound frustration involved in the production.

- Because it’s show business – for recluses.

Allow me to set you a small puzzle:

A bat and ball cost $1.10

The bat costs one dollar more than the ball.

How much does the ball cost?

The correct answer is at the bottom of this post. I’m sure many of you got it right (the problem isn’t difficult, after all), but others will have leapt to the wrong conclusion and answered that the ball costs 10c. What’s more, even those who found the right answer will almost certainly have had the answer “10c” spring unbidden to their minds before putting it firmly to one side. Why?

This puzzle is not my own, as you may have guessed from the choice of currency. I quote it from the book I’m reading at the moment, Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman (2011). Kahneman is a psychologist, but he won the Nobel Prize for Economics – largely by demonstrating that (contrary to the assumptions built into most economic models) human beings are not rational in their decisions when it comes to money, or much else. This is not news to novelists, but Kahneman provides fascinating details about the ways in which our irrationality manifests itself.

I’m not here to review Kahneman’s book, though I highly recommend it, but I want to mention the fundamental model he uses for human judgement and decision making, which I think has some interesting applications to writing. Kahneman talks of two systems, which share the work of thinking. System 1 is intuitive, instinctive, semi-conscious: we use it to do routine tasks such as walking, as well as for our initial judgements of situations. It was your System 1 that came up with the answer 10c. System 2 is conscious, effortful, and sometimes lazy: we bring it to bear in unfamiliar situations, or if we have reason to believe that System 1 isn’t to be trusted. If I ask you to multiply 2x2, System 2 probably won’t need to get involved, but for a sum such as 24x93, it will. Not only that, but the two systems compete for resources. As Kahneman points out, if you ask someone to multiply 24x93 in their head when they happen to be walking, they will typically stop to work it out – to free up extra mental capacity.

When you become expert at something, it becomes less conscious – moving from System 2 to System 1, in Kahneman’s terms. If you’ve learned to drive, or touch-type, you’ll have experienced this: actions that were at first conscious and effortful become “automatic”. In fact, although I touch-type quite well I would be unable to tell you the layout of a QWERTY keyboard: that knowledge has migrated from my conscious mind, where it could be retrieved by System 2, to my fingers. Similarly, I would be hard put to say whether the clutch is to the left of the brake pedal or vice versa. Happily, my feet know.

This has got me to wondering about the roles of Kahneman’s two systems in writing. Writers sometimes find themselves in that luxurious place known as “the zone”, in which consciousness appears to take a step back, and words flow onto the page like honey (but without the mess). On such occasions writing appears effortless, intuitive – the product, one might imagine, of System 1 – and specifically of an expertise that has become automatic. Most of the time, however, it’s not like that, and both systems are involved. System 2 is there, judging whether what we’ve written says quite what we wanted it to; whether it’s in the right place; whether we need it at all. System 1 is taking in the overall shape of the text, and finding it satisfying or otherwise; it’s suggesting dialogue and plot for System 2’s approval. Both systems are unfortunately unreliable: System 1 (as we saw in the puzzle at the top) likes to go for the obvious answer, or (in writing terms) the cliché; System 2 is liable to swing between a lazy dereliction of duty and hypercriticism that can choke writing off entirely. A good and productive writer will be able to find a balance between the two, and judge at any moment which ought to be taking the lead – which rather implies a System 3 for making this kind of decision! In fact, as so often, Plato got there first, with his

allegory of the chariot – but Daniel Kahneman has taken my understanding of my own thought processes a lot further.

What's your experience? Do you recognize these descriptions from your own writing life?

Answer: The ball costs 5c.

My current work-in-progress (work-in-stasis might be a more accurate description) contains an important plot twist, which I’m hoping will catch people by surprise. Don’t ask me, I’m not telling; but it’s got me thinking about plot twists and their evil counterparts, spoilers.

The thing is, while part of me is rubbing my hands with delight at the thought of my twist and the effect it will have my hapless readers, another part is sniffily pointing out that plot twists are cheap tricks, and that a book that relies too heavily on them may be enjoyed once for its shock value, but will never be read twice. All the same, as a reader I enjoy a good plot twist myself, so I would like to arbitrate if I can and achieve a compromise acceptable to both parties.

Let’s start with definitions. All stories contain events, but at what point does a turn of events become a twist? A twist must of course be unexpected, but can we say more than that? One way of thinking about it – a circular one, admittedly, but we’re entering the twisted realm of the Möbius strip here anyway – is to say that a plot twist is an event that, if it were revealed ahead of time, would count as a spoiler. This of course raises the twin question: what is a spoiler? Telling a little about a book’s plot in advance needn't involve spoiling; indeed, it's the very essence of jacket blurbs, which are designed to entice readers into wanting more, not to ruin their enjoyment. At what point does an amuse bouchecease to enhance the appetite and begin to spoil it?

Do spoilers have a sell-by date?

Position within the plot is one relevant factor. A plot twist that comes early enough – say, the revelation that your uncle has murdered your father by pouring poison in his ear – can be very effective, but if it appears near the beginning of the story it merges into exposition. Probably no one would consider themselves “spoiled” by learning this fact about Hamlet, because the play centres on the consequences that flow from the revelation, not on the murder itself. At the other extreme, a plot twist that appears right at the end of a book can seem gimmicky, and successful examples are scarce outside specialized genres such as the detective story. Gene Kemp’s The Turbulent Term of Tyke Tiler (1977) is a rare exception. In general the ideal place for a really fundamental plot twist is the middle third of a story. That gives you time to weave the rug you’re going to pull out from under your readers’ feet, and also time to justify your action in what follows. Frances Hardinge’s excellent new book, Cuckoo Song (2014), is the most recent example of this kind that I have read.

Plot twists are a kind of trick played on the reader, who is led to expect or believe one thing but is then surprised by a reality that is very different. Like all practical jokes spoilers need to have some kind of point to be justified. That sea cook you’ve grown so fond of? He's really the leader of the pirates! But now you’ve let yourself become emotionally involved, and will remain so.

Twists can happen at the level of genre as well as of plot. As my friends will wearily testify, over the last couple of months I have become rather obsessed with a Japanese anime series bearing the ungainly title

Puella Magia Madoka Magica. Before it was broadcast in Japan in 2011, the series was given

this trailer, which promised a cute (not to say saccharine) story about young girls with magical powers and adorable animal friends – something also implied by the cover of the DVD. Even the first couple of episodes don’t deviate wildly from this expectation. However, at a certain point it is rather as if you have settled down with

Winnie-the-Poohand encountered this scene:

In fact, Puella Magia Madoka Magica is a tragic drama, and one of the most brutal and emotionally hard-hitting series you could wish to see. It has several very effective conventional plot twists, but perhaps the greatest is its genre twist: it looks like one kind of story (both to the viewer and, importantly, to the characters), and turns out to be quite another. As I’ve discovered, however, persuading people to watch something that looks like Madoka without spoiling the nature of the series for them can be an uphill task. And now I’ve also spoiled it for you, dear reader.

Or have I? The strange thing about spoilers is that not all of them spoil. When Sophocles wrote Oedipus Rex he was telling a story with a terrific plot twist: the hero turns out to have unwittingly killed his father and married his mother. Yet his audience were well aware of this before watching the play – those ancient Greeks knew their ancient Greek mythology, after all - and it doesn’t appear to have dimmed their enjoyment or that of subsequent generations. The easy explanation is that the play gives us much more than plot twists, and we are richly compensated in the currency of great poetry for our lack of shock. But that’s not quite right, because even when you know what Oedipus is going to discover, it’s still shocking. It’s shocking because he doesn’t know, and we feel with and for him. That is why, even when they have been “spoiled”, the great works, from Oedipus Rex to Puella Magia Madoka Magica, bear repeated readings and viewings.

Probably I should worry less about twists and spoilers, and just try to write the best book I can. If it’s good enough, it will survive whatever spoiling comes its way. Literature, as Ezra Pound, put it, is news that stays news. Or, to paraphrase Professor Kirke: “It’s all in Aristotle. Bless me, what do they teach them in these schools?”

“Thus is Man that great and true Amphibium, whose nature is disposed to live, not onely like other creatures in divers elements, but in divided and distinguished worlds: for though there be but one to sense, there are two to reason, the one visible, the other invisible.”

(Sir Thomas Browne)

Whilst in the park the other day I encountered my old friend and sparring partner, Sir Gradgrind Strawman, who like me was taking his morning constitutional. It wasn't long before the conversation turned to our habitual point of contention, the worth or otherwise of fantasy fiction.

Sir Gradgrind, to do him justice, differs from his Dickensian namesake in that he doesn’t disdain all fiction. It is fantasy alone to which he takes exception. “Escapist nonsense!” he exclaimed. “Ghosts? Unicorns? How can I be expected to believe in things that aren’t real?”

It isn’t the first time he’s made this complaint. On previous occasions I have pointed out that realist fiction (his preferred reading, after cookery books) isn’t “real” either. It’s all made up – that's why they call it fiction. To this he’ll reply in a harrumphing tone: “Perhaps the things in those books didn’t happen – but they could have. They don’t contradict scientific fact. That makes all the difference.”

Today, I decided to take a different tack. “You ask how you can be expected to believe in things that aren’t real? Well, let’s take a look at those words, ‘real’ and ‘believe’…”

You see, I know that when Sir Gradgrind talks about “scientific fact” he has a vague notion of atoms, Newton’s Laws of Motion, evolution and the like. But his knowledge is almost entirely second hand, derived from long-ago school lessons, television documentaries and articles in the weekend supplements. So, when he asserts that the surface temperature of Neptune is -201oC he is really displaying a childlike trust. Not only has he not tested it for himself, he has very little understanding of how real scientists reached this conclusion – any more than he could explain exactly how his mobile phone works, or—

You see, I know that when Sir Gradgrind talks about “scientific fact” he has a vague notion of atoms, Newton’s Laws of Motion, evolution and the like. But his knowledge is almost entirely second hand, derived from long-ago school lessons, television documentaries and articles in the weekend supplements. So, when he asserts that the surface temperature of Neptune is -201oC he is really displaying a childlike trust. Not only has he not tested it for himself, he has very little understanding of how real scientists reached this conclusion – any more than he could explain exactly how his mobile phone works, or—

“What – are you saying that youdon’t believe that the surface temperature of Neptune is -201oC ?” Sir Gradgrind interjected at this point.

“Not at all – I believe it too. I’m simply pointing out that we both take it on faith. We have outsourced the authority to describe physical reality to scientists, just as our equally intelligent forebears outsourced it to Aristotle and Ptolemy, for reasons that seemed as good to them as ours do to us. But we don’t need to go to outer space in order to—ah, Pooh sticks!”

For we had reached the wooden bridge where it was our custom to indulge in a game of Pooh sticks. On this occasion Sir Gradgrind suggested that we “make it interesting” by laying a small wager, the loser being obliged to buy tea and scones in the park café afterwards – a proposition to which I readily assented.

For we had reached the wooden bridge where it was our custom to indulge in a game of Pooh sticks. On this occasion Sir Gradgrind suggested that we “make it interesting” by laying a small wager, the loser being obliged to buy tea and scones in the park café afterwards – a proposition to which I readily assented.

Sir Gradgrind had the better of me at Pooh sticks, but walking to the café I sought to turn the situation to my advantage. For the placing of a bet, it seemed to me, was just the kind of reality-warping event with which his views were ill-equipped to cope. Making a bet is an example of what philosophers call “performative” language. When you use language performatively, you aren’t using it to describe something that already exists, you are bringing something into existence. Bets, promises, wishes, declarations, invitations, bequests, suggestions – all share this magician’s power, to conjure something into the world that wasn’t there before. They are not private fantasies – on the contrary, their validity is widely recognized and may even have force in law. Had I dismissed our bet as a fiction when it was time to pay for the scones, Sir Gradgrind would have been justifiably irked. But was the bet real in quite the same way that the bridge we stood on while making it was real? Sir Gradgrind had to admit that it wasn’t, quite. Yet much of what constitutes human life is built from this kind of material, neither real in the way Sir Gradgrind would be happy to hail as “scientific fact” nor unreal in the way he would be happy to dismiss as “escapist nonsense.” It seems that the Gradgrindian “real” is an unhelpfully binary term, which fails to capture a large part of our experience.

“Belief” presents itself as stiffly binary too. Either you believe something, or you don’t – right? Perhaps when you’re reading a story you can suspend your disbelief (to use Coleridge’s phrase), but that idea still casts belief as a kind of toggle switch, either On or Off.

Yet in practice reading fiction isn’t like that. For example, when we cry at the death of a favourite character, is it because we believe in them? If Yes – if we think that Beth March exists in the same way that Louisa Alcott did – then the implications for our view of the world are profound indeed. If No, then why on earth are we crying over an idea? When we read a horror novel and find ourselves compelled to check under the bed before turning out the light, is it because we really believe in ghosts? Neither Yes nor No adequately describes the case. In reading as in the rest of life we travel neither by land nor by sea but along the shifting foreshore, searching stranded rock pools, caught between reality and unreality, belief and unbelief, affected by and affecting both. The best fantasy fiction, taking this ambiguous aspect of human experience as its subject, reflects it back to us in a particularly direct, one might even say realistic, fashion. Or so I told Sir Gradgrind.

Sir Gradgrind was having none of it, of course. Approaching a large piece of granite statuary in the style of Barbara Hepworth (and momentarily forgetting that each action has an equal and opposite reaction) he swung his foot at it, crying “I refute you thus!”

Sir Gradgrind was having none of it, of course. Approaching a large piece of granite statuary in the style of Barbara Hepworth (and momentarily forgetting that each action has an equal and opposite reaction) he swung his foot at it, crying “I refute you thus!”

I’m sorry to report that he broke his toe in three places.

A couple of weeks ago,

a post by Clementine Beauvais set the cat among the pigeons here on ABBA by questioning whether reading a bad book is always better than reading no book at all. The debate that followed veered at times into a related but slightly different topic, one always likely to be sensitive with authors. What, if anything, makes a book a “bad book” in the first place? The arguments divided commenters into two broad and messily intersecting camps. The first group wished to apply their preferred canons of taste and quality: was the book formulaic, clichéd, incoherent? The second prioritised utility: even a book that was “bad” by other criteria it might still be good for a particular reader at a particular time. By that rule, there was no such thing as an intrinsically “bad” book.

I don't think we can do without either of these approaches entirely – but rather than reopen the argument about poor quality books I’d like to think about how these ideas apply at the other end of spectrum, when we’re singling books out not for opprobrium but for praise. How do we decide whether a book deserves a literary prize?

Children’s books are in strange position here. Adults, aware that they are not children’s literature’s primary audience, can feel quite uncomfortable about choosing books “over children’s heads.” When adults honour a book with a prize, is it because they deem it the “best” by the measures of literary quality they would apply to books written for people like themselves, or are they trying to ventriloquize the judgements of children – whose criteria for a good book may be quite different?

Different prizes deal with this problem in different ways. At one extreme we have the Costa Children’s Book Award, which is chosen by a panel of three adult judges, with – as far as I know – no child input at all. At the other, the Red House Children’s Book Award sells itself in part on the claim that it is “the only national book award voted for entirely by children.” Somewhere in the middle sits the Roald Dahl Funny Prize, in which the votes of hundreds of children are put into the mix, but the final decision is made by an adult panel. Of course, these prizes (and others) are doing slightly different things, but the variety of methods for choosing the “best” book suggests some confusion, even discomfort.

The sense that there are systematic differences between adults’ and children’s tastes is one factor in play here, but there are others. For example, there is the opposition between the technocratic idea that there exist expert readers who by virtue of their expertise (as writers, teachers, librarians, booksellers, etc.) are more qualified than other people to arbitrate quality, and the democratic idea that the way to choose the “best” of anything is by means of a popular vote. The authority of the Red House prize derives not just from the fact that the judges are children but also from the numbers involved.

All of this informs our original dilemma. Are there certain qualities, such as vivid writing, original plot and characterization, etc., that make a book “good”? Or is the quality of a book always to be judged in relation to the circumstances of its reading, so that a book that’s bad for one reader may be good for another, and the best book is the one that does the most good for the most people? In philosophy that would be called a utilitarian position; others may call it rule by lowest common denominator, although for them the question remains – who nominates the denominators? (And who are you calling common?)

Of course, there are other criteria in the selection of literary prize winners besides the ones I’ve mentioned. One is sales. In the United States, the children’s book world was surprised in recent weeks to discover that the right-wing “shock jock” Rush Limbaugh had been nominated as “Author of the Year” by the respected Children’s Book Council. It turns out that

the CBC’s criteria for nomination are entirely determined by an author’s sales rather than by anyone’s literary judgement, child or adult. If you are a millionaire celebrity author who can afford to buy thousands of copies of your own book you can thus guarantee not only “bestseller” status but also a nomination for a major literary award. Nor is this a new phenomenon. For years, it was an open secret that the “recommendations” of a major UK book chain could be purchased by publishers wishing to promote their books.

This approach goes beyond populism – rather, it is money masquerading as popular taste (in the case of the millionaire) or as elite taste (in the case of the UK chain) and trying to create a market in the process. Wordsworth once remarked that that “every great and original writer, in proportion as he is great and original, must himself create the taste by which he is to be relished.” Had Wordsworth read Fredric Jameson he might have added that what is true of great and original writers is even more so of trite and derivative ones. But the methods, arguably, vary.

A few months ago I was asked to give a talk on “Taking Children’s Literature Seriously” to a group of children’s writers.

In a way, it was an open goal: I knew that my audience already took children’s literature seriously, and they knew I did – so all that remained was to congratulate each other on our insight, to list some of the many things that make children’s literature worthtaking seriously (an exercise I leave to the reader), and to indulge in a little well-justified moaning about the ways in which children’s literature tends to be patronized or ignored by the literary establishment and the wider adult world. Like many children’s writers, I’ve been compiling a list of such slights over several decades, at least in my head. I greatly admire the science fiction magazine Ansible’s “As others see us” column, in which the indefatigable Dave Langford has long chronicled the ignorance and snobbery of literary pundits and others regarding SF (you can see a selection here). It would not be hard to create an “As others see us” column for children’s literature too, and in a future ABBA blog I may do just that – but meanwhile it’s notable that one of the most-viewed posts ever made in this place was about just such a snub. These things rankle.

The more I thought about these matters, though, the more it seemed to me that a speech on these lines – while well worth making – would not get to the heart of the problem. Indeed, I’d already read many essays and had many conversations in which the same points had been made at least as eloquently as I could make them, and things hadn’t fundamentally changed as a result. On the contrary, it appears that the case for taking children’s literature seriously is one that needs to be made again and again – not because it is weak but because many adults find it difficult to hear, being too wedded to ideas about childhood that taking its literature seriously would require them to question.

While I was wondering how to illustrate this point, two well-known pieces of Scripture floated into my head. First, St Paul:

When I was a child, I spake as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child: but when I became a man, I put away childish things. For now we see through a glass, darkly: but then face to face. (I Cor 13.11)

Then, Jesus of Nazareth:

Suffer the little children to come unto me, and forbid them not: for of such is the kingdom of heaven. (Mark 10.14)

Both St Paul and Jesus are using children and childhood as metaphors – but interestingly they are doing so in exactly opposite ways. St Paul likens spiritual understanding and grace to growing up and putting away childish things. Jesus likens the same thing to being, or even becoming, in some way like a child, and presumably putting away the self-consciousness and worldliness of adulthood. Who is right? In our society, both these ways of thinking about childhood are so deeply rooted that the contradiction between them is seldom acknowledged.

On the one hand, children are seen as not-quite-finished adults, and accordingly anything associated with them, including children’s literature, tends to be viewed as necessarily inferior, or at best as preparatory for the “real” (i.e. adult) thing. This is why even when children’s books are praised it is often in terms of their being (to use a phrase popular with well-meaning Amazon reviewers) “too good for children”, and when they are dismissed it is because they are seen as limited in range and scope – just like the children who read them.

On the other hand, childhood is often viewed as a time of innocence in need of protection from adulthood – which is why even books for young adults may be criticized on the grounds that “a careless young reader […] will find himself surrounded by images not of joy or beauty but of damage, brutality and losses of the most horrendous kinds.” "Joy and beauty” areof course the agar in childhood’s Petri dish, the proper medium for culturing innocence. Such books are in effect criticized for not being childish enough.

Children’s writers are hence caught in a double bind; but this is only because children are caught in a double bind. The contradictory demands made on writers (“Help children to grow up!” “Preserve childhood innocence!”) are merely reflections of the contradictory demands made on children themselves. In the end, taking children’s literature seriously is just one part of taking children seriously. And that is a lifetime’s work.

A few years ago the children’s book world learned a new word, or a new use for an old one: whitewashing.

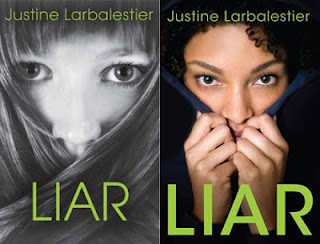

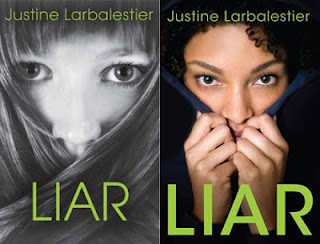

Whitewashing is the term used for the practice of putting a white model on the jacket of a book about a black or other non-white protagonist, in the presumed hope of not "putting off" potential white readers. As one striking and well-known instance, let’s take the case of Justine Larbalestier’s 2009 novel, Liar. The heroine of Liar, Micah, is biracial, and described as having “nappy” hair; but advance copies of Bloomsbury’s US edition showed her as a white girl with straight hair – a move that drew such loud protests (including from Larbalestier herself) that the publisher hastily replaced the cover with one more representative of the book’s contents, as this before-and-after picture shows:

The case of

Liar is far from isolated, and you can read a recent article about the whitewashing phenomenon, with many more examples,

here. The problem isn’t confined to race, however. More recently, an edition of

Anne of Green Gables drew the wrath of many by its portrayal of the red-headed Anne Shirley (whose hair colour is a major plot point) as blonde:

Why did the publishers of this edition give us a blonde Anne? Was it because they believe blondes sell more books than redheads? Was it a fiendish attempt to gain notoriety on the internet, on the principle that there’s no such thing as bad publicity? Possibly, possibly, although in this case another factor may have been lack of a design budget and ignorance of the book’s content: the offending edition of

Anne was self-published, and self-publishing (for all its virtues) has in some cases made badly-designed jackets

a new art form.

So far we’ve had whitewashing and blonde-washing – but there are other wash cycles out there, and not only for jackets. There’s straight-washing, for example. This goes back a long way: as early as 1640 John Benson published an edition of Shakespeare's sonnets with the pronouns changed to make them look as if they were all addressed to a woman. A mere 371 years later, Sherwood Smith and Rachel Manija Brown’s YA novel

Stranger was taken on by a major agent, but

only on condition that one of the main characters, who happened to be gay, was made straight. In a book market where LGBT people, like black people, are

woefully underrepresented compared to their numbers in the real world, especially as protagonists or major characters, this attempt to suppress their appearance was seen by many as pernicious – for society as a whole, but particularly for young LGBT readers.

Being behind the times, I discovered only recently the extent to which some popular Japanese anime cartoons have been straight-washed in the process of being adapted for American viewers. In Japanese manga (comics) and the children’s anime that are based on them, romantic feelings between people of the same sex are frequent, and not generally seen as problematic. For example, in the manga Cardcaptor Sakuraand in the anime of the same name, ten-year-old Sakura (female) has a crush on her older brother’s friend, Yukito (male) – but so does her classmate, a boy named Li. In addition, Sakura’s own female best friend, Tomoyo, is in love with her. When the anime was adapted for American television under the name Cardcaptors, Sakura’s crush on Yukito (now called Julian) was preserved, but Li’s was erased; and Tomoyo’s (now Madison’s) love for Sakura was transformed into non-romantic friendship. So integral were both these threads to the original story that the American censors had to go to great lengths to achieve the change, deleting many scenes in the process (and filling the gaps with irrelevant flashbacks to previous episodes), while making innumerable smaller cuts and changes to dialogue. Even so, Cardcaptors still retains traces of what has been ripped from it, in the form of inexplicable blushes and plot lines that no longer quite make sense. These were a sacrifice apparently seen as worth making on the altar of heteronormativity. Cardcaptor Sakura is not a unique case, either: the adaptors of the anime Sailor Moon went so far as to change the sex of one of the characters (Zoisite) in the English version, so as to render him (now her) acceptably straight.

Are things getting better, or worse? It's hard to say. The story of Sherwood Smith's and Rachel Manija Brown’s rejection provoked understandable outrage, and perhaps as a result appears to have acquired

a happy ending: their book is now after all to be published as written. As for anime, the examples I've cited are over a decade old, and I'm told by people more knowledgeable than I that there haven't been any recent cases of straight-washed English-language versions of Japanese anime. That doesn't mean that same-sex romance has found its way onto English-speaking children's cartoons, however. If we wish to increase the representation of LGBT characters, perhaps that's not such a huge amount of progress, after all? Meanwhile, cases of whitewashing (and its variants) continue to crop up regularly; girls are featured less prominently on book jackets than boys (even when equally prominent in the story); fat characters are portrayed as thin - and so on, and on. Editorial and marketing decisions will always tend to drift in the direction of safety and perceived "norms". If that's to change, it's up to writers and readers to pull hard in the other direction.

Fiction for adults, fiction for children – which is more complex?

The obvious answer is that books for adults are generally more complex than books for children. They use a wider vocabulary, more sophisticated language, deal in “adult” concepts and experiences, are fluent in abstract ideas and thoughts, and assume a familiarity with literary genres and devices that cannot be counted on in the average child reader.

Once we look carefully at this list, however, some of its items appear rather less solid. First, not all books for adults are in fact particularly sophisticated. Literary fiction of the kind that makes the Man Booker shortlist represents only a small percentage of the adult fiction published and sold, and it would misleading to take Hilary Mantel and her peers as representative of “adult fiction”. Moreover, if the vocabulary of (some) children’s books is limited, this need not imply simplicity: ask Hemingway or William Blake. Nor are sophisticated post-modern devices such as intertextuality, frame-breaking, genre-mixing and

mise en abyme the preserve of adult literature: in fact, they are probably found more often in picture books for young children, from Lauren Child’s

Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Bookto the Ahlbergs’

Jolly Postman.

It’s true that children’s books don’t generally deal with specifically adult experiences such as old age or marital infidelity (although some do); but equally, adult books don’t in general deal with the specific experiences of children, such as going to school for the first time. None of these experiences is more, or less, deserving of treatment in fiction than the others.

What about plots, though? Are the plots of adult books more complex than those of children’s books? Here I’m reminded of

an article written by Diana Wynne Jones shortly after she started writing adult fiction in the early 1990s, having already been a children’s writer for almost twenty years. She explains that her assumptions were in fact the opposite – that a point she would have explained only once in a book for children she felt the need to repeat several times for adult readers: “These poor adults are never going to understand this; I must explain it to them twice more and then remind them again later in different terms.” This idea derived from her experience of being told by adults that they found the plots of some of her children’s books hard to follow (and that therefore they must be "too difficult for children"). Children themselves, however, never seemed to have any difficulty. Jones’s explanation is an interesting one:

Children are used to making an effort to understand. They are asked for this effort every hour of every school day and, though they may not make the effort willingly, they at least expect it.

Adults, by contrast, are used to knowing things already, and their tolerance for uncertainty – negative capability would be a good term, if Keats hadn’t already nabbed it – is correspondingly less. All of us, when we read a novel, will encounter unfamiliar ideas and unexplained facts. I suppose we must have a kind of mental “holding pen” in which to place such items, in the hope that they will be clarified and resolved at some later point. But perhaps children’s holding pens have a greater capacity than those of adults, simply because they are more accustomed to dealing with new experiences? If so, we might expect them to be more able to deal with complex plots – and, in that sense at least, to be more sophisticated readers.

I don’t think that’s a complete answer to the rather silly question with which I started – because of course complexity is multifaceted – but I do find it an intriguing idea. In any case, if I ever see an adult book with as complex a plot as Jones’s

Hexwood I'll be very surprised.

A financial post seems in order, in honour of the Budget – always a nervous time for authors, as for other small businesses.

Apparently, the Chancellor is planning to start issuing us all with personal Tax Statements, showing how the money we pay in tax is divided between the various departments of Government. Serendipitously, I’d been thinking about such matters in any case, ever since an American colleague (in a children’s literature discussion group in a far distant corner of the internet) directed my attention to this sobering diagram showing the spending patterns of the average American family. (If you want to see the thing full size, click here.)

It’s an interesting chart in several ways, but the part that captured my colleague’s attention – and mine – was the pitiful proportion of the average family budget that was spent on ‘Reading’ - just $118, or 0.2%. To put this in perspective, this is 22 times less than is spent on eating outside the home ($2,668, or 5.4%), or on ‘Entertainment’ ($2,698, also 5.4%).

Now, it’s not clear that the figures would be exactly the same for the UK, though I suspect they wouldn’t be very different. It may also be that some book purchases are hidden away under ‘Education’. Just possibly people are reading a lot, but doing it at the library (I wish!). But even making reasonable allowances for all these, it seems clear that literature looms small indeed in the average household budget – somewhere between Tissue Paper and Loo Roll.

It was Roald Dahl day on Tuesday. Dahl would have been 95.

The day got some unwelcome publicity with the announcement by the Dahl Museum in Great Missenden that they were trying to raise £500,000 in order to move and restore the garden shed in which Dahl wrote many of his most famous works. Blogs and tweets ensued, many to the effect that a) that was a hell of a lot of money for a shed, and b) why couldn’t the well-heeled Dahl Estate pay for it?

I have sympathy with both points, but still, you’ve got to hand it to Dahl. There aren’t many writers who have museums devoted to them, and I can’t think of any, other than Burns, Shakespeare and Joyce, who have a “Day”. Even twenty-one years after his death, Dahl shoots effortlessly into the headlines, pushing aside Libya and the meltdown of the Eurozone, merely on the basis that his garden shed is a bit damp.

It’s harder for children’s writers to survive than writers for adults, simply because childhood doesn’t last as long, and their audience must be constantly renewed. Ideally they need to write for a long time, preferably for a generation. At that point, the people who enjoyed the early books are old enough to have children of their own, and may start buying all over again, sta

"Every shop in Clapham high street appears to have been looted. The only shop that has escaped is Waterstone’s.” BBC Radio (via Nick Green)

“This fire he beheld from a tower in the house of Maecenas, and being greatly delighted, as he said, with the beautiful effects of the conflagration, he sung a poem on the ruin of Troy, in the tragic dress he used on the stage.” Suetonius, Life of Nero

“Why read literature? The answer, in a nutshell, was that it made you a better person. Few reasons could have been more persuasive than that. When the Allied troops moved into the concentration camps [...] to arrest commandants who had whiled away their leisure hours with a volume of Goethe, it appeared that someone had some e

Thanks for flagging these up, Cathy - at a time of what feels like constant compromise, some battles are still worth fighting!

To be honest, I'm surprised that characters of ten were allowed even a heterosexual crush. My experience of books that publishers want to sell into the American market is that no sexual content at all is really acceptable - at least not if they hope to get it into a school library.

Some of the errors just fall under the category of stupidity - or of cover-designers not reading the book. The Anne of GG, for instance, is probably not an anti-readhead choice. There are as many books in which the dog or horse on the cover is the wrong colour/breed, or the landscape shows the wrong country, etc.

I agree with you, regarding white-washing particularly, but I do think there is also a large margin of gross incompetence in some of the other examples rather than 100% iniquitous malice.

You know American publishers better than I do, Stroppy, but I should have made it clear that in talking about a crush and romantic feelings I don't mean "sexual content" in any explicit sense. At least, no more than would be implied by a ten-year-old swooning over Justin Bieber, which I find it hard to believe would be considered beyond the pale.