We celebrate the 50th anniversary of the holiday classic with a gallery of rare artwork from the film.

The post ‘How The Grinch Stole Christmas!’ is 50 Years Old Today—And It’s Still Great appeared first on Cartoon Brew.

Add a Comment

We celebrate the 50th anniversary of the holiday classic with a gallery of rare artwork from the film.

The post ‘How The Grinch Stole Christmas!’ is 50 Years Old Today—And It’s Still Great appeared first on Cartoon Brew.

Add a Comment

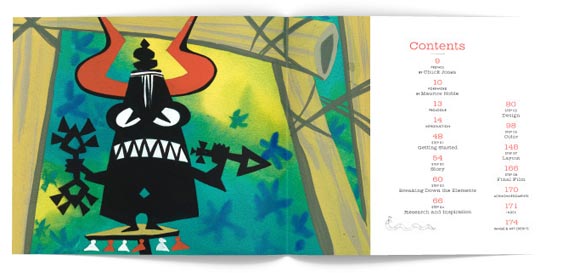

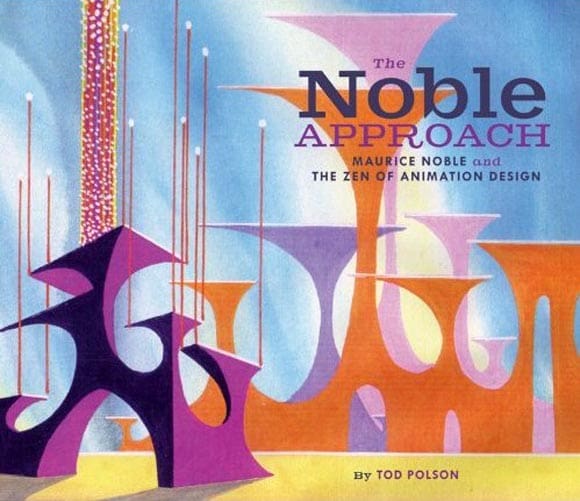

The Noble Approach: Maurice Noble and

The Zen of Animation Design

By Tod Polson, based on the notes of Maurice Noble

(Chronicle Books, 176 pages, $40, pre-order for $26.50 on Amazon)

By the modest standards of celebrity in the animation world, Maurice Noble is already a rockstar. Few Golden Age layout artists and background designers, with the exception of Eyvind Earle, Mary Blair, and possibly Jules Engel, command Noble’s name recognition. Maurice’s fame is primarily attributable to his long-term association with Warner Bros. director Chuck Jones.

Noble’s collaborations with Jones include such classics as Robin Hood Daffy, Duck Dodgers in the 24½th Century, What’s Opera, Doc?, How the Grinch Stole Christmas!, The Dot and the Line and the long-running Wile E. Coyote/Roadrunner series. Thanks to that beloved resume, Noble has been spared the ignoble anonymity of so many other classic animation artists.

With such standing in the animation world, and even an entire book-length biography already devoted to his life, one could reasonably expect that everything that could be said about Noble has already been said. Tod Polson’s The Noble Approach proves that that’s not the case. Polson has put together an irresistible package that fuses biography and art instruction, each of its page filled with invaluable insights and incredible artwork, much of it never-before-published.

Polson is one of the Noble Boys, the informal name given to a group of men (and women) whom Noble trained throughout the 1990s at studios like Chuck Jones Film Productions, Turner Feature Animation and his own company, Noble Tales. The Noble Boys have gone on to big things in the animation industry: Ricky Nierva was the production designer of Pixar’s Up and Monsters University; Don Hall directed Disney’s Winnie the Pooh and is writing and directing the upcoming Big Hero 6; Jorge Gutierrez co-created the Nick series El Tigre: The Adventures of Manny Rivera and is directing Reel FX’s 2014 feature Book of Life.

Some of the Noble Boys encouraged Maurice to write down his thoughts about design and layout for an eventual book. Polson has adeptly compiled and edited those notes for this book, and has combined them with the remembrances of the other Noble Boys about their interactions with Maurice and lessons learned from him, as well as archival interviews with Noble and original commentary from artists like Susan Goldberg and Michael Giaimo.

Polson devotes thirty-four pages of the book to providing a biography of Noble that follows his path which began professionally at Disney on films like Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and Bambi. In spite of its brevity, this biographical section manages to be more revealing and historically well-rounded than the disappointing 2008 book Stepping into the Picture: Cartoon Designer Maurice Noble by Robert J. McKinnon. That well-intentioned book missed the mark—badly. It was understandable that McKinnon’s layperson understanding of the animation process prevented him from providing the kind of process detail that is in Polson’s new book, but his sins of omission made it a letdown as personal biography, too.

Basic and vital details about Noble’s personal and professional relationships that were omitted in that earlier biography are thankfully included in Polson’s book. For example, we learn hat Mary Blair and Maurice Noble were not only classmates at Chouinard Art Institute, but also a romantic couple. That’s a revealing historical tidbit considering that Noble’s giddy use of color is second in animation only to Mary Blair. Polson clearly expresses Noble’s unflattering thoughts about Sleeping Beauty production designer Eyvind Earle, with whom he worked during the production of the industrial film Rhapsody of Steel, whereas the earlier biography only vaguely acknowledged that Noble “may have had some difficulty working with Earle.” Polson also discusses Noble’s more-important-than-acknowledged role on Chuck Jones’ Oscar-winning short The Dot and the Line, an issue that was left untouched in the earlier book.

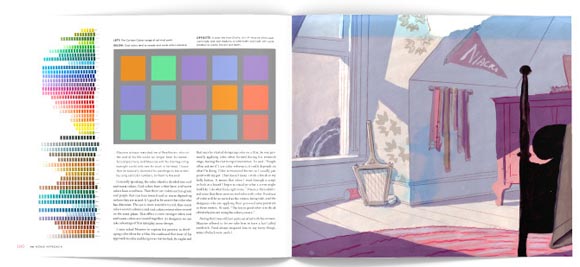

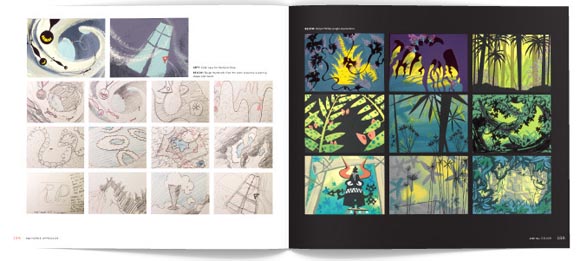

For all its historical value, the real meat of the Noble Approach follows the biography. In these subsequent sections, we learn Noble’s artistic process step-by-step from the start of a film to its completion. Chapters are devoted to starting a film, story, breaking down the elements, research, design, color, layout, and an oddly ineffectual and anticlimatic two-page chapter devoted to the finished film.

The material covered in these chapters will undoubtedly be familiar to anyone with an art background—values, contrast, simplifying elements, visual hierarchy, compositional grids—but the examples of Maurice’s own work gives us a fresh entry point into these topics. The section on color is particularly fantastic. Color is one of the hardest elements to get right in animated film, and Maurice knew how to walk the thin line between playful and tacky. Polson does a superb job of explaining how Maurice managed to do this by doing a deep analysis of his color palettes.

The section on color, for all its strengths, also represents one of the parts of the book that I wish the author had expanded his scope. Polson makes clear from the outset that this is “Maurice’s book,” but I can’t help but think our appreciation for Noble would have been enhanced further by offering some discussion of his contemporaries at Warner Bros., like layout artist Hawley Pratt and background painter Paul Julian. Contrasting the color theories of Julian, who was the studio’s true master of color in my opinion, would have been an enlightening sidetrip.

A lot of the best information the book isn’t technical, but rather practical advice and the wisdom of experience. This is true of Noble’s thoughts on selling an idea:

To be a successful designer, being able to sell a good idea is just as important as coming up with the idea itself. It’s hard to sell something simply because you think it feels right. You have to be able to logically discuss why it feels right.

—and his thoughts on why the production methods of yesteryear produced better cartoons:

There is more talent working in the industry now than ever before, but sadly the vast majority won’t have the opportunity to work on really good creative stories. The problem isn’t always the type of stories being told; it’s more in the way these stories are being told and developed. There is no room for visual exploration. There is no time for thought and craftsmanship. There isn’t the chance for crews to build trust and synergy.

The production design tips that he offers are applicable to artists today, even if the tools of the trade have changed:

I suggest putting all your research materials away once you start designing and never refer to them again. This may prove difficult at first. But I’ve found that if you are tied too closely to your reference, your designs will tend to look stiff. You will miss out on many fun design opportunities.

or…

Starting rough and not getting specific too early will allow you to keep your design ideas flexible…The more ideas and work you have, the more design possibilities you will have to choose from.

The Noble Approach: Maurice Noble and the Zen of Animation Design ranks among the most unique and delightful animation books in recent memory. It goes without saying that the book’s mix of technical tips and advice makes it a must-buy title for professional artists and students, but it should also appeal to fans of classic of animation who will surely gain a renewed appreciation for the Chuck Jones canon. The book will be released on October 1st. For those who are still in need of convincing, the book’s official blog gives a nice sense of the book’s content.

In their new episode, the podcast 99% Invisible profiles legendary layout artist Maurice Noble. Noble made significant contributions to Disney films like Dumbo and Bambi, but he is better known for his layout and design work with Chuck Jones on memorable Warner Bros. shorts like Duck Amuck, Duck Dodgers in the 24½th Century, Ali Baba Bunny, What’s Opera, Doc?, and the Road Runner/Wile E. Coyote series.

That’s why it may be surprising for many readers to learn in this podcast about the personality battles between Noble and Jones, and how the two men weren’t particularly fond of one another despite their frequent collaborations. The subjects who were interviewed for the podcast are reliable authorities on Noble: his biographer Bob McKinnon; Tod Polson whose upcoming book about Noble’s techniques will be a must-own; and Pixar artist Scott Morse, who worked with Noble early in his career.

(Thanks, Bob Flynn)

Add a Comment

Ready…set…pre-order Tod Polson’s book about legendary Warner Bros. layout man Maurice Noble. The book is called The Noble Approach: Maurice Noble and the Zen of Animation Design. Publisher is Chronicle Books; street date is May 31, 2013. Retails for $40, Amazon price is $26.40.

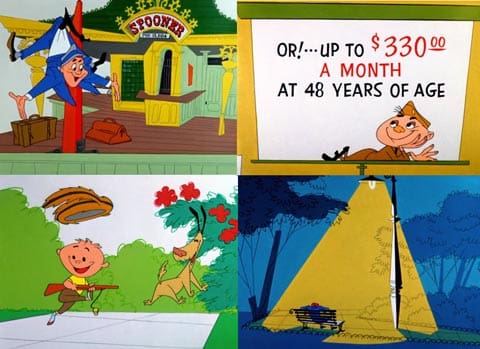

The post about the 1955 Chuck Jones short A Hitch in Time was well received, so let’s complete the story. Jones made at least two more military propaganda films following that one—90 Day Wondering in 1956 and Drafty, Isn’t It? in 1957.

The gem of the bunch may be 90 Day Wondering. I’d seen some of Maurice Noble’s layout concepts for this short when researching the book Cartoon Modern, but regretfully, hadn’t seen the short. It is an absolutely fantastic example of the ‘cartoon modern’ aesthetic, with an astounding level of craft that is far beyond the needs of the plebeian ideas expressed in the film.

The first minute of the film has an expert piece of temporal and spatial compression. We follow the main character’s ecstatic journey out of the military and back to his hometown while he runs around in a whirlwind a la the Tasmanian Devil. It’s also a great use of animated movement to illustrate the inner emotions of a character.

When the main character is finally revealed to the audience, he has arrived at his hometown of Spooner, which also happens to be Maurice Noble’s birthplace (Spooner Township, Minnesota). Noble is at his peak of layout powers in this short. He plays liberally with exaggeration of shapes in the background, perspective, pattern and color, and thinks nothing of it to key some of the backgrounds in full color while using stark white backdrops for other scenes in the film.

The main character, Ralphie, is designed with more realism than one might expect of a Warner Bros. cartoon, but that is a direct consequence of the cartoon’s purpose, which was first and foremost to convince military personnel to re-enlist. Ralphie’s realistic design also plays a nice contrast to the cartoonier characters Pete and Re-Pete, who play the role of his conscience.

It’s a thrill at this late date to discover new Chuck Jones cartoons from the Fifties. It’s also educational. Looking at Jones films that I’ve never seen allows me to be objective about their quality in a way that I can’t be about the classic Jones shorts that I’ve seen dozens of times.

This trio of military-propaganda shorts that Jones made is phenomenally impressive. Jones’s crew brings a level of expertise and professionalism to the table that is woefully lacking (dare I say, completely absent) in much of today’s cartoon animation. If anything, the films should serve as a reminder that almost any idea or concept can be enhanced by animation if the animation is entrusted to filmmakers who are passionate about the craft of visual storytelling.

Add a Comment

Tod Polson (El Tigre, The Secret of Kells) announced recently that he’s putting together a book on Maurice Noble that will be published in 2012 by my pals at Chronicle Books. Polson knew him as well as anybody, and I have no doubt he’s going to make this something special. This book will not only give Maurice his due, it’ll also make up for the disappointingly shallow biography of Noble that was published a few years back.

Tod describes the project on his blog:

The last few years of his life, Maurice had been working on a design textbook that described his approach to design. Unfortunately he passed away before he was able to complete the text. For most of the last year I have been working with Chronicle Books in putting together what I hope will be the book that Maurice had dreamed of. It will be chocked full of his pre-production art, notes, and thoughts from the master himself describing his process. The book will also be full of reflections from folks that knew and worked with him.

Cartoon Brew: Leading the Animation Conversation |

Permalink |

No comment |

Post tags: Chronicle Books, Maurice Noble, Tod Polson