In April this year, we questioned whether or not you could match the quote to the philosopher who said it. After demonstrating your impressive knowledge of philosophical quotations, we've come back to test your philosophy knowledge again. In this second installment of the quiz, we ask you if you can make the distinction between Aquinas, Hume, Sophocles, and Descartes?

The post Can you match the quote to the philosopher? Part two [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

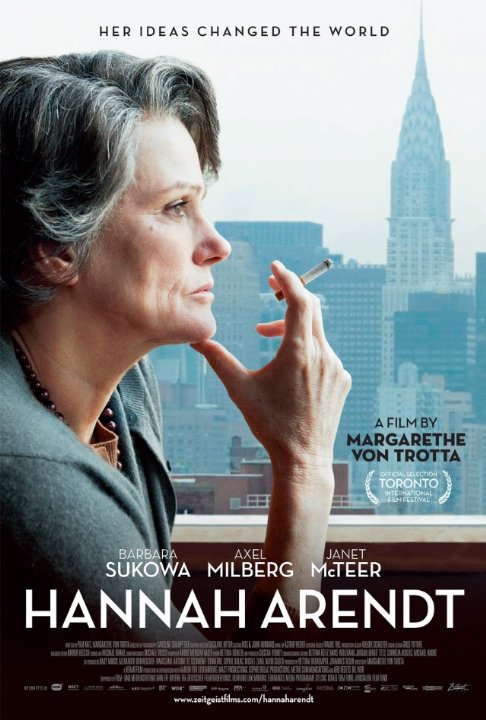

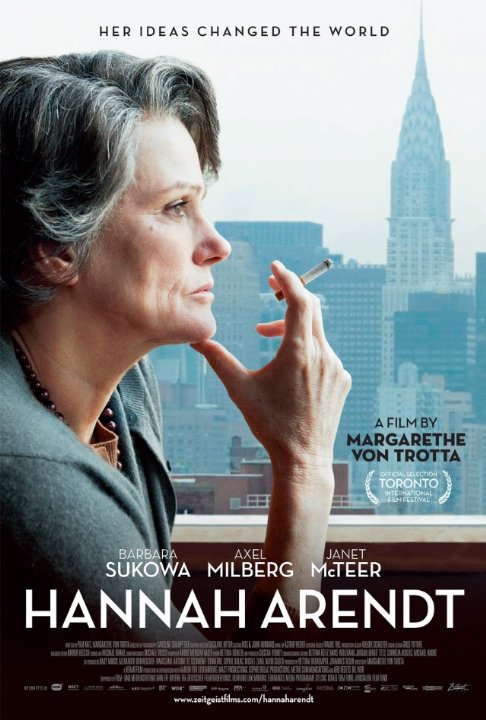

The OUP Philosophy team have selected Hannah Arendt (4 October 1906- 4 December 1975) as their September Philosopher of the Month. Born into a Jewish German family, Arendt was widely known for her contributions to the field of political theory, writing on the nature of totalitarian states, as well as the resulting byproducts of violence and revolution.

The post Philosopher of the month: Hannah Arendt appeared first on OUPblog.

Film is a powerful tool for teaching international criminal law and increasing public awareness and sensitivity about the underlying crimes. Roberta Seret, President and Founder of the NGO at the United Nations, International Cinema Education, has identified four films relevant to the broader purposes and values of international criminal justice and over the coming weeks she will write a short piece explaining the connections as part of a mini-series. This is the second one, , following The Act of Killing.

By Roberta Seret

The powerful biographical film, Hannah Arendt, focuses on Arendt’s historical coverage of Adolf Eichmann’s trial in 1961 and the genocide of six million Jews. But sharing center stage is Arendt’s philosophical concept: what is thinking?

German director, Margarethe von Trotta, begins her riveting film with a short silent scene — Mossad’s abduction of Adolf Eichmann in Buenos Aires, the ex-Nazi chief of the Gestapo section for Jewish Affairs. Eichmann was in charge of deportation of Jews from all European countries to concentration camps.

Margarethe von Trotta’s and Pam Katz’s brilliant screen script is written in a literary style that covers a four-year “slice of life” in Hannah Arendt’s world. The director invites us into this stage by introducing us to Arendt (played by award-winning actress Barbara Sukova), her friends, her husband, colleagues, and students.

As we listen to their conversations, we realize that we will bear witness not only to Eichmann’s trial, but to Hannah Arendt’s controversial words and thoughts. We get multiple points of view about the international polemic she has caused in her coverage of Eichmann. And we are asked to judge as she formulates her political and philosophical theories.

Director von Trotta continues her literary approach to cinema by using flashbacks that take us to the beginning of Arendt’s university days in Marburg, Germany. She is a Philosophy major, studying with Professor Martin Heidegger. He is the famous Father of Existentialism. Hannah Arendt becomes his ardent student and lover. In the first flashback, we see a young Arendt, at first shy and then assertive, as she approaches the famous philosopher. “Please, teach me to think.” He answers, “Thinking is a lonely business.” His smile asks her if she is strong enough for such a journey.

“Learn not what to think, but how to think,” wrote Plato, and Arendt learns quickly. “Thinking is a conversation between me and myself,” she espouses.

Arendt learned to be an Existentialist. She proposed herself to become Heidegger’s private student just as she solicited herself to cover the Eichmann trial for The New Yorker. Every flashback in the film is weaved into a precise place, as if the director is Ariadne and at the center of the web is Heidegger and Arendt. From flashback to flashback, we witness the exertion Heidegger has on his student. As a father figure, Heidegger forms her; he teaches her the passion of thinking, a journey that lasts her entire life.

Throughout the film, in the trial room, in the pressroom, in Arendt’s Riverside Drive apartment, we see her thinking and smoking. The director has taken the intangible process of thinking and made it tangible. The cigarette becomes the reed for Arendt’s thoughts. After several scenes, we the spectator, begin to think with the protagonist and we want to follow her thought process despite the smoke screen.

When Arendt studies Eichmann in his glass cell in the courtroom, she studies him obsessively as if she were a scientist staring through a microscope at a lethal cancer cell on a glass slide. She is struck by what she sees in front of her – an ordinary man who is not intelligent, who cannot think for himself. He is merely the instrument of a horrific society. She must have been thinking of what Heidegger taught her – we create ourselves. We define ourselves by our actions. Eichmann’s actions as Nazi chief created him; his actions created crimes against humanity.

The director shows us many sides of Arendt’s character: curious, courageous, brilliant, seductive, and wary, but above all, she is a Philosopher. Eichmann’s trial became inspiration for her philosophical legacy, the Banality of Evil: All men have within them the power to be evil. Man’s absence of common sense, his absence of thinking, can result in barbarous acts. She concludes at the end of the film in a form of summation speech, “This inability to think created the possibility for many ordinary men to commit evil deeds on a gigantic scale, the like of which had never been seen before.”

And Eichmann, his summation defense? It is presented to us by Willem Sassen, Dutch Fascist and former member of the SS, who had a second career in Argentina as a journalist. In 1956 he asked Eichmann if he was sorry for what he had done as part of the Nazis’ Final Solution.

Eichmann responded, “Yes, I am sorry for one thing, and that is I was not hard enough, that I did not fight those damned interventionists enough, and now you see the result: the creation of the state of Israel and the re-emergence of the Jewish people there.”

The horrific acts of the Nazis speak for themselves. Director von Trotta in this masterpiece film has stimulated us to think again about genocide and crimes against humanity, their place in history as well as in today’s world.

Roberta Seret is the President and Founder of International Cinema Education, an NGO based at the United Nations. Roberta is the Director of Professional English at the United Nations with the United Nations Hospitality Committee where she teaches English language, literature and business to diplomats. In the Journal of International Criminal Justice

, Roberta has written a

longer ‘roadmap’ to Margarethe von Trotta’s film on Hannah Arendt. To learn more about this new subsection for reviewers or literature, film, art projects or installations, read her

extension at the end of this editorial.

The Journal of International Criminal Justice aims to promote a profound collective reflection on the new problems facing international law. Established by a group of distinguished criminal lawyers and international lawyers, the journal addresses the major problems of justice from the angle of law, jurisprudence, criminology, penal philosophy, and the history of international judicial institutions.

Oxford University Press is a leading publisher in international law, including the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, latest titles from thought leaders in the field, and a wide range of law journals and online products. We publish original works across key areas of study, from humanitarian to international economic to environmental law, developing outstanding resources to support students, scholars, and practitioners worldwide. For the latest news, commentary, and insights follow the International Law team on Twitter @OUPIntLaw.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post Hannah Arendt and crimes against humanity appeared first on OUPblog.

By Gerald Steinacher

April 11, 1961 marked the beginning of the trial against Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem. In the course of the trial, the world came face to face with the reality of the Holocaust or what the Nazis called the “final solution of the Jewish problem” – the killing of 6 million people. Newspapers around the world published thousands of articles about Eichmann and his role in the Holocaust. But what none of the international journalists touched upon was probably the most intriguing aspect of Eichmann’s story: the way in which he, the bureaucrat of the Holocaust, managed to escape justice soon after the war and flee to Argentina.

The prominent philosopher Hannah Arendt, who closely followed the trial in Israel, was one of those who wondered why Eichmann’s escape never attracted more international attention. In her famous book Eichmann in Jerusalem she wrote “the trial authorities, for various reasons, had decided not to admit any testimony covering the time after the close of the war.” It seems that there was a conscious effort to restrict the dissemination of information on how Eichmann managed to escape to Argentina. This part of his story was to remain largely a secret, which took historians more than fifty years to uncover.

We now know what the Israeli authorities kept hidden during the Eichmann trial: the involvement of Vatican circles, Western intelligence services, various governments and the International Committee of the Red Cross in the escape of Eichmann and thousands of other Nazis, war criminals, and Holocaust perpetrators. A picture has emerged that raises many uncomfortable questions. It is clear that the agencies involved knew exactly what they were doing, but were able to justify the decisions they made and the actions they took with the Cold War. After all, as the Third Reich lay in ruins, the only enemy left for the Western Powers was the communist Soviet Union. In the eyes of the Catholic Church, communism was a ‘godless, deadly enemy’, even worse than Nazism.

After laying low in Germany for several years, in 1950 Adolf Eichmann decided to immigrate to Argentina. He used a tried route through Italy, where he acquired a new identity as Riccardo Klement, a South Tyrolean from Bolzano, and a travel document from the Red Cross. In Italy he was helped by the Vatican Aid Commission for Refugees, in cooperation with a small group of catholic priests, former SS comrades and some Argentinean officials. The ease with which he reached Argentina was also the result of Western intelligence services, such as the CIA and the German BND, turning a blind eye to where Eichmann was hiding. Research suggests that they knew of his new identity as Riccardo Klement, but ignored the information. But why would the Israeli government be so careful not to reveal any of this during Eichmann’s trial? The true reasons are unclear, but it is possible that Israelis simply did not want to embarrass governments and institutions who were now their allies.

Riccardo Klement’s life on the run came to an abrupt end in May 1960, when he was kidnapped by Israeli government agents just outside of his home in Buenos Aires and taken to Jerusalem: “I, the undersigned, Adolf Eichmann, hereby declare out of my own free will that since now my true identity has been revealed, I see clearly that it is useless to try and escape judgment any longer.” Eichmann had to stand trial and in the process the world came to know the horrible details about the treatment of Jews in Nazi Germany, from their forced emigration to centrally- planned industrialized genocide. But the world had to wait 50 years longer to finally learn the truth about how some of the worst Holocaust perpetrators fled justice and who were the institutions helping them do it.

0 Comments on Eichmann in Jerusalem as of 1/1/1900