By Anthony Scioli, Ph.D.

“Just look at the gladiators… and consider the blows they endure! Consider how they who have been well-disciplined prefer to accept a blow than ignominiously avoid it! How often it is made clear that they consider nothing other than the satisfaction of their [coach] or the [fans]! Even when they are covered with wounds they send a messenger to their [coach] to inquire his will. If they have given satisfaction to their [coach], they are pleased to fall. What even mediocre gladiator ever groans; ever alters the expression on his face? Which one of them acts shamefully, either standing or falling? And which of them, even when he does succumb, ever contracts his neck when ordered to receive the blow?”

The above passage, with the exception of two minor word substitutions on my part, was written by Cicero 2,000 years ago. My point is that his description of the sacrificial gladiator of the ancient amphitheater can be applied all too easily to the players who currently do battle on the modern gridiron.

The above passage, with the exception of two minor word substitutions on my part, was written by Cicero 2,000 years ago. My point is that his description of the sacrificial gladiator of the ancient amphitheater can be applied all too easily to the players who currently do battle on the modern gridiron.

I am convinced that football, in its present form, cannot last. I will put aside the physical carnage that piles up every weekend, the torn cartilage, broken bones, blackened, bruised and ripped skin, the shredded muscle fibers; I am not a physician. However, I am a psychologist. From my perspective, I believe that the greatest health crisis precipitated by football involves the brain and the mind, especially for those at the professional level, and particularly for those who are retired, and have suffered one too many concussions. For these former gladiators, there is a great risk of succumbing to severe, life-threatening forms of hopelessness.

The hopelessness that descends upon the retired professional football player should not be a surprise. It is understandable if you begin with some knowledge of what changes occur in a soft and mushy brain that has been repeatedly concussed, or more bluntly, tossed and smashed from side to side within a bony skull-box. Repetitive brain trauma can result in Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE)

CTE has been detected in the brains of ex-football players well as former boxers. In CTE, there are signs of a spreading tau protein that normally serves a stabilizing function but becomes dislodged, primarily from the axons which transmit nerve impulses. The floating Tau form a spreading tangle of tissue that disrupts brain function. Rare diseases can precipitate this pathological cascade but so can repetitive head trauma. CTE has also been found in the aged, and those stricken with Alzheimer’s disease. The most commonly affected areas include the frontal lobes (decision-making, planning, willpower), the temporal lobes (memory and speech), and the parietal area (sensory integration, reading and writing). The most common emotional symptoms in those suffering from CTE include depression, anger, hyper-aggressiveness, irritability, diminished insight and poor judgment.

On 2 May 2012 former football star Junior Seau shot himself in the chest with a .357 magnum. Eighteen months earlier, Seau had driven his SUV off a cliff following an arrest on charges of domestic violence. He claimed that he had fallen asleep. Back then, many in his circle of friends and family hoped and prayed it was the truth. His brain was sent to a team of researchers at the Boston University School of Medicine. Their tests revealed a brain besieged by CTE.

A little more than a year earlier, in February, 2011, Dave Duerson, also a former professional football player, similarly committed suicide by shooting himself in the chest. He had texted a message to his family indicating that he was “saving” his brain for research. Three months later BU School of Medicine confirmed “neurodegenerative disease linked to concussions.” In high school, Duerson had been a member of the National Honor Society and played the sousaphone, traveling Europe with the Musical Ambassadors All-American Band. He attended the University of Notre Dame on both football and baseball scholarships. He graduated with honors, receiving a BA in Economics. Duerson played eleven seasons in the NFL.

Whenever interviewed, the researchers at the Boston University School of Medicine are reluctant to affirm a cause and effect link between CTE and suicide. They provide the typical (and not unreasonable) response that multiple causes often underlie human behavior, including suicide. While generally true, a case such as that of Duerson seems to beg the question, what else besides CTE could have led a formerly intelligent, well-organized, responsible, and successful individual to morph into a desperate failure that ends his own life at the age of fifty?

Anthony Scioli is Professor of Clinical Psychology at Keene State College. He is the co-author of Hope in the Age of Anxiety with Henry Biller. Dr. Scioli completed Harvard fellowships in human motivation and behavioral medicine. He co-authored the chapter on emotion for the Encyclopedia of Mental Health and currently serves on the editorial boards of the Journal of Positive Psychology and the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. Read his previous blog articles.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Stockphoto image via OxfordWords blog.

The post Why football cannot last appeared first on OUPblog.

By Anthony Scioli

From late December to the middle of January it is obligatory for people to make one or more New Years’ resolutions. Recent surveys reveal that the most common resolutions made by Americans include losing weight, getting fit, quitting smoking, quitting drinking, reducing debt, or getting organized. This list dovetails perfectly (unfortunately) with an international study of 24 character strengths which revealed that Americans rate themselves lowest in the virtue of “self-regulation”.

Ironically the other leading American resolutions involving getting or doing more rather than having or doing less. Americans want more socializing, more joy, and more learning. We want less and we want more. Should anyone be surprised that resolutions often fail to bring about lasting change?

Less than a handful of psychological studies have been done on New Years’ resolutions. There is scant advice in the database for the layperson to glean except that resolutions are more likely to be successful if an individual is more motivated and a goal is perceived as more important. This is not very helpful “self-help”.

As a psychologist, I would suggest that instead of a piecemeal focus on narrow goals that is bound to fail, people should aim for a higher horizon, a commitment to a more hopeful way of life.

Lighthouse. Photo by Fylkesarkivet i Sogn og Fjordane. Creative Commons License.

Deep below the surface of many desperate resolutions reside the most primitive fears. The dramatic turn of the calendar on December 31st is a reminder of finitude on many levels, most poignantly, the fact that an individual has one less year. In the northern hemisphere this reminder comes when the nights are long and wind blows hard and cold. However, regardless of where one lives, a different freeze may be felt, what the existentialists call an “ego chill”, the sudden and full awareness that one day you will cease to exist.

The projected fears of the New Year are the same as the deathbed regrets of the dying. They are the twin fears of a self-aware being. “Did I live to my life to the fullest?” Have I have left a mark on the world?”

There is a strong need to feel that one did not leave too much unlived life “on the table”. Emerson put it this way:

“Our fear of death is like our fear that summer will be short, but when we have had our swing of pleasure, our fill of fruit, and our swelter of heat, we say we have had our day”.

Human beings also fear the specter of oblivion. Aristotle went so far as to coin the term entelechy to refer to an essential momentum within all living things to continue to be or exist, without end, in one form or another. I believe that we all have some form of entelechy etched into our DNA.

In Living A Life That Matters, Rabbi Harold Kushner wrote, “In my forty years as a rabbi, I have tended to many people in the last moments of their lives…The people who had the most trouble with death were those who felt that they had never done anything worthwhile in their lives, and if God would only give them another two or three years, maybe they would finally get it right. It was not death that frightened them; it was insignificance, the fear that they would die and leave no mark on the world.”

The answer to this existential dilemma is to live a double-life. You should balance being anchored in the here and now with investments focused on a more transcendent plane. The scientific psychology of the 20th century focused more and more on the here and now. The most obvious, and in my view, overrated example of this is the concept of “mindfulness”. At best, mindfulness, or an intentional, nonjudgmental awareness of the present is a corrective Eastern strategy for the distracted and hurried mind of the West. It is not a full program for living. Not only is it impractical to live just for the present but such a philosophy does not match up with the architecture of the brain which is dominated by the frontal lobes and other structures designed for projecting into the future or preserving the past. Human beings were meant to live in 3D, the past, present, and future.

In contrast, the American psychology of the 19th century was initially influenced by “moral philosophy”. From about 1850 to 1890, it was not uncommon for psychologists to focus on more transcendent issues such as character, values, religion, or coping with death. In the 21st century we need a more integrated philosophy.

Living a “Double – Life”

There is an old adage that “where there is life there is hope”. I would turn this around. I believe where there is hope, there is life. I understand hope as a composite of four basic needs: attachment (trust and openness), mastery (purpose and collaboration), survival (self-regulation and liberation), and spirituality (empowerment, connection, and salvation linked to a larger perceived force or entity). If you want to live more fully in the here and now while also investing in something more enduring, commit in 2013 to a life that includes more time for building and nurturing relationships, for articulating a mission in life, for increasing your perceived degrees of freedom, and for spiritual fulfillment. You will not only feel happier on a daily basis, but you will be far more likely to build an enduring legacy. Towards this end, I offer eight recommendations, two each for the four cardinal elements of hope (one for the left brain and one for the right brain).

Attachment

Attachments may be the most significant sources of hope. Note that even the perennial classics of the holiday season such as A Christmas Carol, It’s a Wonderful Life, and the Auld Lang Syne song (Should Old Acquaintance be forgot, and never thought upon?) all deal with the primacy of relationships.

For left brain attachment read Thornton Wilder’s The Bridge of San Luis Rey. For your right brain, follow this up with a live viewing of his play, Our Town. If you are seeking inspiration to nurture your relationships, it is difficult to find two better sources.

Mastery

Six months before his assassination, Martin Luther King Spoke about mastery to a group of Junior High School Students in Philadelphia.

“If it is your lot to be a street sweeper, sweep streets like Michelangelo painted pictures, sweep streets like Beethoven composed music, sweep streets like Leontyne Price sings before the Metropolitan Opera. Sweep streets like Shakespeare wrote poetry. Sweep streets so well that all the hosts of heaven and earth will have to pause and say: Here lived a great street sweeper who swept his job well.”

For left brain mastery, go to the positive psychology website at the University of Pennsylvania and take their VIA Survey of Character Strengths. Find out what your top five strengths are and find ways to craft your life around these virtues. For right brain mastery, listen to Martin Luther King’s “I have a dream” speech.

Click here to view the embedded video.

Survival

Survival hope is strongly infused with a sense of liberation. In contrast, the most common experience in hopelessness is a sense of entrapment. The psychologist Rollo May contrasted freedom of doing with freedom of being. To maximize your freedom of doing, May suggested making the most of your potential or taking advantage of various forms of fate or destiny such as your genetics or time and place of birth. He also noted that when your freedom of doing is restricted, as a human being, you always have the freedom to be, to adopt a particular attitude.

For left brain survival hope, I would read Man’s Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl. As a psychiatrist who survived the Nazi concentration camps, Frankl describes how he found hope by maximizing both types of freedom. For right brain survival hope I would follow Frankl with a viewing (or re-viewing) of the film Life is Beautiful.

Spirituality

For left brain spiritual development reflect on your spiritual type. Spiritual needs and passions will flow from your particular type. Are you a mystic seeking a sense of oneness? Are you a follower seeking structure? Are you an independent seeking support for a chosen path? Are you a collaborator looking to join forces with a powerful other? Are you a sufferer who seeks comfort? Are you a reformer seeking justice? For right brain spiritual development, I would review your list of favorite songs and find one or two that match up with your spiritual type and play them often in 2013. You can find music consistent with your particular religious affiliation that will nevertheless address your particular spiritual type. Here are six suggestions: For independent types: the Chariots of Fire theme; for followers, “Amazing Grace”; for collaborators, “Lord of the Dance”; for mystics, “Unchained Melody”; for sufferers, “Let It Be” (the Beatles); for reformers, “A Change is Gonna Come” (Sam Cooke).

Anthony Scioli is Professor of Clinical Psychology at Keene State College. He is the co-author of Hope in the Age of Anxiety with Henry Biller. Dr. Scioli completed Harvard fellowships in human motivation and behavioral medicine. He co-authored the chapter on emotion for the Encyclopedia of Mental Health and currently serves on the editorial boards of the Journal of Positive Psychology and the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. Read his previous blog articles: “Why spring is the season of hope” and “Contrasting profiles in hope.”

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only psychology articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post A better New Year’s resolution: commit to hope appeared first on OUPblog.

By Anthony Scioli

Spring and hope are intertwined in the mind, body, and soul. In spring, nature conspires with biology and psychology to spark the basic needs that underlie hope: attachment, mastery, survival, and spirituality. It is true that hope doesn’t melt away in the summer; it isn’t rendered fallow in autumn nor does it perish in the deep freeze of winter. But none of these other seasons can match the bounty of hope that greets us in the spring. My reflections on hope and the spring season are cast in terms of metaphors.

Mind Metaphors

More than three decades ago, linguist George Lakoff and philosopher Mark Johnson demonstrated how metaphors can reveal the inner structure of private feelings. For example, when we refer to “high hopes,” we are revealing something about the phenomenology of the hope experience, that it is “buoyant,” “uplifting,” even “energizing.”

Metaphors of Hope

My research as well as that of psychologists Shlomo Breznitz and James Averill has identified a number of hope metaphors. Below are the four most striking examples.

Light and Heat

Hope has been compared to light and heat. Karl Menninger called hope the “indispensable flame” of mental health. English writer Martin F. Tupper wrote, “though the breath of disappointment should chill the sanguine heart, speedily it glows again, warmed by the live embers of hope.”

Spring also brings added light and heat, sometimes so suddenly that we speak of a virtual “spring fever.” The first day of spring marks the vernal equinox, a balance of daylight and darkness. In the Northern Hemisphere this amounts to an average increase of three hours of light since the winter solstice, roughly a 20% gain. With increased light come a host of direct and indirect effects that improve mood and engender hope. Most directly, increased serotonin is produced. Serotonin is a major excitatory neurotransmitter in the nervous system, and the target of many antidepressant drugs. Among the indirect effects of spring on mood are increased exercise, and the physically related but psychologically distinct activities of gardening and farming.

Like spring, hope is also a 50-50 proposition. If our odds of achieving a particular outcome fall to less than fifty percent, we tend towards “despair.” If we are more than fifty percent certain of an outcome, we become “optimistic.” When psychologist James Averill and his colleagues surveyed individuals about their chances of realizing various hopes, the average response was fifty percent. For this reason, I believe that some kind of faith, not necessarily the religious type, but something essentially “spiritual,” must be present to ground our hopes.

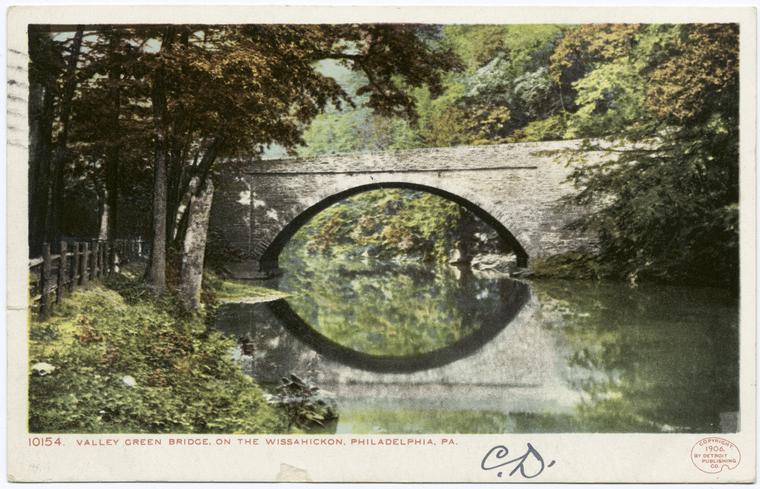

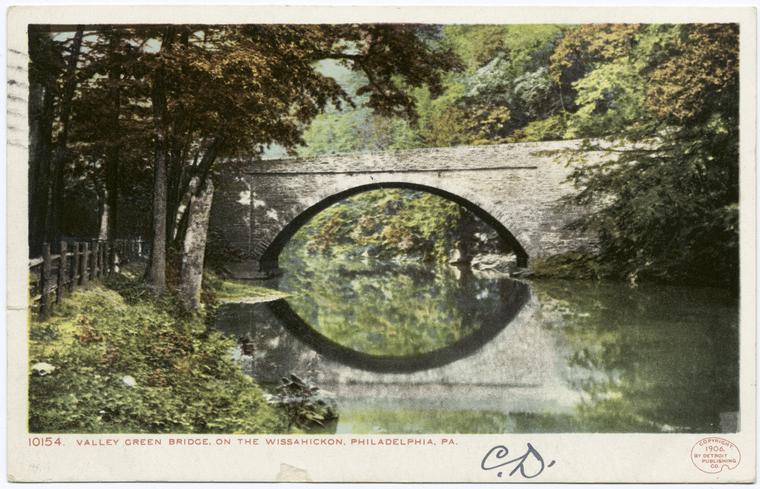

Valley Green Bridge on the Wissahickon, Philadelphia, Pa. Detroit Publishing Company postcards. Source: NYPL.

A Bridge

Hope has been likened to a bridge that can actively transport the individual from darkness to light, from entrapment to liberation, from evil to salvation.

0 Comments on Why spring is the season of hope as of 1/1/1900

The above passage, with the exception of two minor word substitutions on my part, was written by Cicero 2,000 years ago. My point is that his description of the sacrificial gladiator of the ancient amphitheater can be applied all too easily to the players who currently do battle on the modern gridiron.

The above passage, with the exception of two minor word substitutions on my part, was written by Cicero 2,000 years ago. My point is that his description of the sacrificial gladiator of the ancient amphitheater can be applied all too easily to the players who currently do battle on the modern gridiron.