By Dennis Baron

The English language is full of paradoxes, like the fact that “literally” pretty much always means ‘figuratively.’ Other words mean their opposites as well–”scan” means both ‘read closely’ and ’skim.’ “Restive” originally meant ’standing still’ but now it often means ‘antsy.’ “Dust” can mean ‘to sprinkle with dust’ and ‘to remove the dust from something.’ “Oversight” means both looking closely at something and ignoring it. “Sanction” sometimes means ‘forbid,’ sometimes, ‘allow.’ And then there’s “ravel,” which means ‘ravel, or tangle’ as well as its opposite, ‘unravel,’ as when Macbeth evokes “Sleepe that knits up the rauel’d Sleeue of Care.”

No one objects to these paradoxes. But if you say “I literally jumped out of my skin,” critics will jump on your lack of literacy. Their insistence that literally can only mean, well, ‘literally,’ ignores the fact that word has meant ‘figuratively’ for centuries.

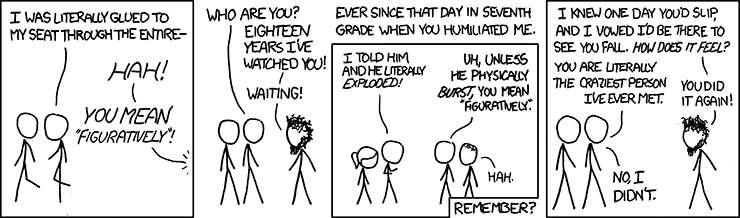

If you’re tempted to correct someone’s figurative use of literally, remember, nobody likes a smartass. (courtesy of XKCD)

The English language is full of paradoxes, like the fact that “literally” pretty much always means “figuratively. Other words mean their opposites as well–”scan” means both ‘read closely’ and ’skim.’ “Restive” originally meant ’standing still’ but now it often means ‘antsy.’ “Dust” can mean ‘to sprinkle with dust’ and ‘to remove the dust from something.’ “Oversight” means both looking closely at something and ignoring it. “Sanction” sometimes means ‘forbid,’ sometimes, ‘allow.’ And then there’s “ravel,” which means ‘ravel, or tangle’ as well as its opposite, ‘unravel,’ as when Macbeth evokes “Sleepe that knits up the rauel’d Sleeue of Care.”

No one objects to these paradoxes. But if you say “I literally jumped out of my skin,” critics will jump on your lack of literacy. Their insistence that literally can only mean, well, ‘literally,’ ignores the fact that word has meant ‘figuratively’ for centuries.

The literal meaning of literally, which enters English around 1584 at a time when the vocabulary was really exploding, is ‘by the letters.’ The word comes from Latin littera, which means ‘letter,’ as in the letters of the alphabet, so writing something out literally meant writing it letter by letter. But by 1646 literally had developed its first extended sense, ‘word for word.’ A literal translation is one done word for word, not letter by letter. And by the 19th century Byron uses literally to mean something even more general, ‘a faithful rendering.’ His poem “Churchill’s Grave, a fact literally rendered” (1813) may be a faithful rendering of what Byron saw when he visited the poet Charles Churchill’s grave, but its use of literally is undeniably figurative. This sense of ‘faithful rendering’ is what people who insist on a literal reading of sacred texts or the constitution mean: it’s a figurative use of literal to mean ‘faithful to the original intent,’ assuming such intent can ever be determined.

Today few people use literally