new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Politics and Current Events, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 25 of 25

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Politics and Current Events in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

“Doctrinal Problems”*

It may seem odd that we see so many constraints on expression in traditional public forums in light of today’s generally permissive First Amendment landscape. In recent years, the Supreme Court has upheld the First Amendment rights of video gamers, liars, and people with weird animal fetishes. But in most cases involving the public forum—cases where speech and assembly might actually matter to public discourse and social change—courts have been far less protective of civil liberties.

Part of the reason for this more tepid judicial treatment of the public forum is a formalistic doctrinal analysis that has emerged over the past half-century. Courts allow governmental actors to impose time, place, and manner restrictions in public forums. These restrictions must be “reasonable” and “neutral,” and they must “leave open ample alternative channels for communication of the information.”

The reasonableness requirement is an inherently squishy standard that can almost always be met. The neutrality requirement means that restrictions on a public forum must avoid singling out a particular topic or viewpoint. For example, they cannot limit only political speech or only religious speech (content-based restrictions0. And they cannot limit only political speech expressing Republican values or only religious speech expressing Jewish beliefs (viewpoint-based restrictions). It turns out to be pretty easy for government officials to satisfy the neutrality requirement.

The requirement of “ample alternative channels” introduces another highly subjective standard. Lower courts have found that an alternative is not sufficiently ample “if the speaker is not permitted to reach the intended audience” or if the distance between speaker and audience is so great that only those “with the sharpest eyesight and most acute hearing have any chance of getting the message.” But the ampleness standard is otherwise underspecified. At least one federal appellate court has concluded that an alternative venue need not be within “sight and sound” of the intended audience.

The Supreme Court’s only recent consideration of the ampleness standard came in its deeply divided opinion in Hill v. Colorado, which upheld a public forum restriction that had been challenged by anti-abortion protestors. The majority opinion concluded that the restriction left open “ample alternative channels for communication” and did “not entirely foreclose any means of communication.” Justice Anthony Kennedy warned in dissent that “our foundational First Amendment cases are based on the recognition that citizens, subject to rare exceptions, must be able to discuss issues, great or small, through the means of expression they deem best suited to their purpose.” Kennedy insisted “it is for the speaker, not the government, to choose the best means of expressing a message.” That sentiment echoes Justice William Brennan’s assertion in an earlier case: “The government, even with the purest of motives, may not substitute its judgment as to how best to speak for that of speakers and listeners; free and robust debate cannot thrive if directed by the government.” The underspecified ampleness standard can substantially hinder these goals.

As long as the requirements of reasonableness, neutrality, and ample alternative channels are met, officials can limit the duration and time of day when public forums can be used, the location of an expressive event, and the way in which ideas are conveyed. In principle, these restrictions make sense. In practice, they have been used to control and mute expression and voice.

Consider, for example, how restrictions on time can sever the link between message and moment. Closing a public forum for periods of time that encompassed symbolic days of the year like September 11, August 6 (the day the United States detonated an atomic bomb on the city of Hiroshima), or June 28 (the anniversary of the Stonewall Riots) could stifle political dissent. Time restrictions that closed the public sidewalks outside of prisons on days of executions, outside of legislative buildings on days of votes, or outside of courthouses on days that decisions are announced, would raise similar concerns. Yet all of these restrictions are arguably permissible under current doctrine.

Restrictions on place that preclude access to symbolic settings can be similarly distorting. As law professor Timothy Zick has noted, “Speakers like abortion clinic sidewalk counselors, petition gatherers, solicitors, and beggars seek the critical expressive benefits of proximity and immediacy.” Zick observes that current doctrine means “individuals who wish to engage in speech, assembly, and petition activities are too often displaced by a variety of regulatory mechanisms, including the construction of ‘speech zones.'” Take, for example, a labor protest. A strike that occurs in front of an employer’s business rather than blocks or miles away not only communicates to a different audience but also conveys different meanings.

Restrictions on manner can drain an expressive message of its emotive content. A ban on singing could weaken the significance of a civil rights march, a funeral procession, or a memorial celebration. Manner restrictions can also eliminate certain classes of people from the forum altogether. That might be true of a requirement that all expression be conveyed by handbills or leaflets rather than by posters. As Supreme Court Justice William Brennan once observed, “The average cost of communicating by handbill is . . . likely to be far higher than the average cost of communication by poster. For that reason, signs posted on public property are doubtless ‘essential to the poorly financed causes of little people.'”

Under current doctrine, the state’s regulation of public spaces through time, place, and manner restrictions is too easily justified apart from serious inquiry into the implications of those restrictions. A government official can usually come up with some reason to regulate expressive activity, some explanation of neutrality, and some argument that an ample alternative for communication exists. But the First Amendment should require more than just any justification to overcome its presumptive constraint against government action.

Sometimes the government can go to even greater extremes than the latitude afforded under time, place, and manner restrictions. Under an evolving doctrine known as government speech, the government can characterize some expression as distinctively its own and not subject to any First Amendment review.

Not all applications of the government speech doctrine are problematic; some cases are easy to understand. When the City of Pawnee hosts a tribute to black history on Martin Luther King Jr. Day, it is “speaking” a message consistent with Dr. King’s values. To that end, it need not ensure that members of the Ku Klux Klan have an opportunity to present their perspective. The event is premised on government speech rather than on facilitating a diversity of viewpoints and ideas.

Even though we can readily grasp the easy cases, the government speech doctrine is fiercely contested by courts and legal scholars because the line drawing it requires beyond those easy cases is impossible to configure. And without any lines—if the government could claim its own speech in any possible forum—the doctrine would swallow the First Amendment.

The Supreme Court unwisely gestured toward the possibility of the unrestricted government speech doctrine in its 2009 decision Pleasant Grove v. Summum. In that case, an obscure religious group called Summum wanted to erect a stone monument in a city park in Pleasant Grove City, Utah. Summum argued that because Pleasant Grove’s park was a traditional public forum, the city could not limit the privately donated monuments in the park to those representing certain mainstream groups, like a statue of the Ten Commandments. The city responded that the park space was a limited resource that could only accommodate a limited number of monuments, and insisted that it could choose which ones to include. In some ways the city’s argument makes sense—public parks are finite resources and cannot possibly accommodate every monument that every person wanted to contribute. But rather than addressing that issue within a public forum analysis, the Supreme Court ducked the issue by designating the monuments in the city par as government speech. That meant Pleasant Grove could decide which monuments to allow and which ones to prohibit. Sidestepping the public forum analysis avoided the hard work that courts and officials should be required to undertake in these settings.

*This excerpt has been adapted (without endnotes) from Confident Pluralism: Surviving and Thriving through Deep Difference by John D. Inazu (2016).

***

To read more about Confident Pluralism, click here.

In timely coincidence with today’s primaries and the book’s return to print, The Last Hurrah by Edwin O’Connor received some well-tailored praise from Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist David Hall, writing in the Columbia Daily Herald, who suggests we:

Take a breather from the daily pounding of politics and reflect: chaos, confusion, and gutter campaigning are not new. . . . Even today’s politics are not speeding away. We have survived travail through democracy. Good and thoughtful fiction lets us pause and reflect.

Honing in on The Last Hurrah, an almost-story adapted from the life of notorious Boston mayor James Michael Curley, he writes of the book’s foreboding about the nature of the relationship between media and politics:

Another poignant tale of American politics is The Last Hurrah by Edwin O’Connor. Set in an old and mainline northeastern city, the novel examines the dying days of machine politics when largess held voters in sway. Frank Skeffington, 72, believes he is entitled to one more term. His political compass loses its bearing against a young, charismatic challenger, void of political experience but adorned with war medals and good looks. O’Connor’s 1956 novel was prescient in portraying the impact television would have on politics. While The Last Hurrah lacks the intellectual complexity of All the King’s Men, it raises good questions about how religion, ethnicity, class and economics foster into political alliance—questions still relevant starting even at the city and county level.

To read more about The Last Hurrah, click here.

A free chapter from Sixteen for ’16: A Progressive Agenda for a Better America

by Salvatore Babones (Policy Press)

***

Back in the good old days, that is to say the mid-1990s, taxpayers with annual incomes over $500,000 paid federal income taxes at an average effective rate of 30.4%. For 2012, the latest year for which data are available, the equivalent figure was 22.0%.

The much-ballyhooed January 1, 2013 tax deal that made the Bush-era tax cuts permanent for all except the very well-off will do little to reverse this trend: The deal that passed Congress only restores pre-Bush rates on the last few dollars of earned income, not on the majority of earned income, on corporate dividends, or on most investment gains.

Someone has had a very big tax cut in recent years, and the chances are that someone is not you. In the 1990s taxes on high incomes were already low by historical standards. Today, they are even lower. The super-rich are able to lower their taxes even further through a multitude of tax minimization and tax avoidance strategies.

The very tax system itself has in many ways been structured to meet the needs of the super-rich, resulting in a wide variety of situations in which people can multiply their fortunes without actually having to pay tax. In general, it is also much easier to hide income when most of your income comes from investments than when your income is reported on regular W-2 statements from your employer direct to the IRS.

Whatever our tax statistics say about the tax rates of the super-rich, we can be sure they are lower in reality. At the same time that their tax rates are going down, the annual incomes of highly paid Americans are going through the roof.

In the 1990s the average income of the top 0.1% of American taxpayers was around $3.6 million. In 2012 it was nearly $6.4 million.6 And yes, these figures have been adjusted for inflation. Thanks to the careful database work of Capital in the Twenty-First Century author Thomas Piketty and his colleagues, it is now relatively easy to track and compare the incomes of the top 1%, 0.1%, and 0.01%. The historical comparisons don’t make for pretty reading.

Forget the merely well-off 1%. In the 21st century the top 0.1% of American households have consistently taken home more than 10% of all the income in the country, up from 3% in the 1970s.7 And these figures only include realized income: that is to say, income booked and reported to the tax authorities. If you own a company that doubles in value but you don’t sell any shares, you don’t have any income. Ditto land, buildings, airplanes, yachts, artwork, coins, stamps, etc.

High inequality plus low taxes equals fiscal crisis. The rich are taking more and more money out of the economy, but they are not returning it in the form of taxes. The result is that the US government no longer has the resources it needs to properly govern the country. The country needs universal preschool, universal healthcare, and a massive government-sponsored jobs program. The country needs a complete renewal of its crumbling human and physical infrastructure. The country needs funds for everything from the cleanup of atomic waste in Hanford, Washington to improvements at the National Zoo in Washington, D.C. And the country needs higher taxes on today’s higher incomes to pay for it all.

In 2010 the United States government collected a smaller proportion of the nation’s total national income in income taxes than at any time since 1950.8 That figure has since rebounded, but it is still well below the average from 1996-2001. Under current law the federal income tax take is projected to rise from the historic low of 6.1% in 2010 to 8.6% of national income in 2016. This is an improvement over recent years, but it is still far below the average of 9.5% for the years 1998-2001, the last time the federal government actually ran a budget surplus.

The top marginal tax rate on the highest incomes is now 39.6%, as it was in the 1990s. This is still a far cry from the 50% top tax bracket of the 1970s or the 70% top tax bracket of the 1960s, never mind the 91-92% top tax brackets of the 1950s.10 The return to 1990s levels is a good start, but the next President should push to go much farther back because the tax system has been moving in the wrong direction for a very long time. High incomes are much higher than they ever were and people with high incomes pay much less tax than at almost any time in our modern history. The result, unsurprisingly, has been the enormous concentration of income among a small, powerful elite documented by Piketty in Capital in the Twenty-First Century but no less obvious for all to see.

The concentration of income among a powerful elite may be very good for members of that elite, but it is bad for our society, bad for our democracy, and even bad for our economy. Socially, highly concentrated incomes undermine our national institutions and warp our way of life. For example, people who can afford to send their children to exclusive private schools cease to care for the health of public education, or they erect barriers to separate “their” public schools from everyone else’s public schools. Similarly, people who can afford the very best private healthcare care little about ensuring high-quality public healthcare. People who fly private jets care little about congestion at public airports. People who drink imported bottled water care little about the poisoning of rivers and underground aquifers. Enormous differences in income inevitably create enormous distances between people. The United States is starting to resemble the fractured societies of Africa and Latin America, where the rich live in ated “communities” with armed guards who enforce the exclusion of the lower classes—except to allow them entry as maids and gardeners.

These nefarious effects of inequality can already be seen in America’s sunbelt cities, where there are fine gradations of gated communities: armed guards for the super-rich, unarmed guards for the merely well- off, keypad security for the middle class, and on down the line to the unprotected poor. We should be ashamed, one and all.

Politically, highly concentrated incomes threaten the integrity of American democracy by fostering corruption of all kinds. When the income differences between regulators and the industries they regulate are small, we can count on regulators to look after our interests.

But when industry executives make two or three (or ten) times as much as regulators, it is almost impossible to prevent corruption. Even where there is no outright corruption, it is impossible for regulators to retain talented staff. People will take modest income cuts to work in secure public sector employment. They will not take massive income cuts. Those who do are often just doing a few years on the inside so they can better evade regulation when they go back to the private sector. When doing a few years on the inside includes serving in Congress merely as way to get a high-paying job as a lobbyist, we are in serious trouble.

Along with highly concentrated incomes come vote buying and voter suppression. When the stakes are so high, people will play dirty. No one knows how many local boards of one kind or another around the country have been captured by local economic interests, but the number must be very large.

Economically, highly concentrated incomes ensconce economic privilege, suppress intergenerational mobility, and can ultimately lead to the total breakdown of the free market as a system for effi driving production and consumption decisions. Privilege is perpetuated by excessive incomes because with enough money the advantages of wealth overpower any amount of talent and effort on the part of those who are born poor.

Nineteenth-century English novels were obsessed with inheritance and marriage because in that incredibly unequal society birth trumped everything else. Twenty-first-century America has now reached similar levels of income concentration among a powerful elite. To make this point graphically clear, a family with a billion-dollar fortune that does absolutely no planning to avoid the 40% tax on large estates and no paid work whatsoever can comfortably take out $15 million a year to live on (after taxes, adjusted for inflation) in perpetuity until the end of history—while still growing the estate. That’s how mind-bogglingly large a billion-dollar fortune is.

But probably the least recognized impact of high inequality on our economy is that it severely impairs the efficient operation of the free market itself. Market pricing is at its core a mechanism for rationing. The market directs limited resources to the places where they command the highest prices. The basic idea of rationing by price is that prices encourage people to carefully weigh their purchases against each other—in other words, to economize.

In an economy where everyone earns roughly the same income, rationing by price works just fine for most goods. People take care of their necessities first. Then they can choose whether to spend their extra money on eating out, taking vacations, renovating their homes, or saving up to buy something big like a boat. Because all of these goods are priced in the same currency, people can directly compare their values against each other. And if everyone has roughly the same amount of money to spend, market prices represent roughly the same values for different people. If you and I have the same income, a $20 restaurant meal means as much to me as it does to you.

Problems set in when incomes are very unequal. For people with extraordinarily high incomes, prices become meaningless. What does a $20 restaurant meal mean to someone who makes $20 million a year? Nothing.

The result is incredible waste as the market economy no longer forces people to economize. When rich people accumulate dozens of cars, maintain yachts they only use once a year, or have servants order fresh-cut flowers every day for houses they rarely visit, they are wasting resources that could be put to much better use by other people. Waste like this invalidates the foundational principle of modern economics: that the market maximizes the total utility of society.

That principle only holds if a dollar has the same meaning for you as it does for me. Highly concentrated incomes undermine the whole idea of the market as an economy—that is, as something that economizes. And that is the strongest argument for much higher taxes on higher incomes. There are many ways to reduce inequality, but the simplest and most efficient way is through taxation. The goal of income taxes should be to tilt the field so that earning an after-tax dollar means just as much to a CEO as to a fast food worker. That’s why a 90% marginal tax on incomes over a million dollars is entirely appropriate.

For a poor person who pays no income tax, a $20 restaurant meal costs $20. That person must make a real sacrifice to eat out. For a CEO with a 90% marginal tax rate, a $20 restaurant meal costs $200 in before-tax income. That may not be a huge sacrifice for someone who makes several million dollars a year, but it does change the equation. A CEO may not hesitate to eat out, but may hesitate to buy a private jet when flying business class will suffice.

To be sure, we need higher taxes on higher incomes to raise money for government. But we also need higher taxes on higher incomes just to make the economy work properly. That’s why the economy worked so much better in the high-tax 1950s and 1960s than it has since.

The ultimate goal of income taxes should be to make money as meaningful to a millionaire as it is to you or me. If we can’t quite get there in the next few years, we can certainly get closer than we are. One of President Obama’s most important accomplishments has been to set us on the path toward economic sanity by raising taxes on the highest incomes. The next President should build on this legacy—and in a big way.

***

Salvatore Babones is associate professor of sociology and social policy at the University of Sydney.

To read more about Sixteen for ’16, click here.

The Party Decides: Presidential Nominations Before and After Reform is having quite a week—and quite an election season, in general. The book was adopted early by Nate Silver at his FiveThirtyEight blog, which led to explorations of its hypothesis here and here, and most recently here: where Silver posits the book as the most “misunderstood” of the 2016 primary season.

The point of Silver’s statement rests on whether or not a Trump nomination would destroy the Republican Party. The book’s argument is that party elites—unelected insiders—control who ultimately ends up nominated at the convention, and that decision is made many months before the primary campaign season even begins. Was anyone but Trump the nominee (say Marco Rubio, or even Jeb Bush), then The Party Decides had it right all along; if Republicans put forward DT, then it may be less a sign that the statistically supported data of the book is incorrect, and more a case of the possible dissolution of the Grand Old Party.

In the meantime, you can hear more about the book and what a Trump nomination might signify on today’s episode of The Brian Lehrer Show below:

To read more about The Party Decides, click here.

From Sam Tanenhaus’s review of Nut Country: Right-Wing Dallas and the Birth of the Southern Strategy for the New York Times Book Review:

Whenever we’re in danger of forgetting that the modern Republican Party is captive to a movement, one new excitement or another will jolt us back to reality — whether it is a trio of high-flying presidential candidates who’ve collectively served not a single day in elective office or an uprising by congressional Jacobins giddily dethroning their own leader. Each new insurrection feels spontaneous even as it revives antique crusades to abolish the Internal Revenue Service, “get rid” of the Supreme Court or — most persistent of all — rejuvenate the Old South. Half a century before Rick Perry indicated secession might be an option for Texas, John Tower, the state’s first Republican senator since Reconstruction, accepted the warm greeting of his new colleague, Senator Richard Russell, the Georgia segregationist, who reportedly said, “I want to welcome Texas back into the Confederacy.”

Tower is one of the more statesmanlike figures in “Nut Country,” Edward H. Miller’s well-researched and briskly written account of Dallas’s transformation from Democratic stronghold to “perfect test kitchen” of a new politics of Republican protest that combined the libertarian cry for “freedom” with the states’ rights model of constitutional order.

A go-getting paradise with an economy enriched by government contracts (aerospace and defense), Dallas might seem a curious place for anti-Beltway insurgency. But dependency bred anxiety, and “wealth and fear” took form together, as the journalist Theodore H. White observed in 1954. The tide of newcomers, many from the Midwest, inhaled the fumes of “Texanism,” according to White “a synthetic faith that lets them oppose all the controls and exactions of the federal government in Washington as an invasion of sacred and immemorial rights, while at the same time providing, with its frontier and vigilante memories, a complete answer to the newer problems of minorities, labor and the complexities of city living.”

One of the new Dallas Republicans was Bruce Alger, a Princeton graduate and disciple of Ayn Rand, elected to the House of Representatives in 1954. Initially an Eisenhower supporter, he declined to sign the notorious “Southern manifesto,” with its defiant sneer at civil rights, but soon became an “artful champion of Jim Crow.” In November 1960, four days before the presidential election, he led a group of 300 protesters who converged on a downtown Dallas hotel and accosted Lyndon and Lady Bird Johnson when they entered the lobby. Television cameras captured the moment — along with Alger holding aloft a placard that read “L.B.J. Sold Out to Yankee Socialists” — helping to plant the image of Dallas as a “city of hate.”

To read more about Nut Country, click here.

Richard H. King’s Arendt and America considers a unique reception history—that of America on Hannah Arendt, and not the other way around. Situating Arendt within the context of US intellectual, political, and social history, King examines how time spent in her adopted homeland and the relationships she formed while living there allowed her the necessary time and space to develop some of her most compelling contributions to critical thought, including the idea of the modern republic as an alternative to totalitarian rule, and the concepts behind the “banality of evil.” Recently, Kind engaged in an hour-long interview with Lillian Calles Barger, for the New Books in Intellectual History series.

From that interview’s header:

Her interests were neither social nor cultural, but the political sphere. In Cold War America, she became part of a moral center of the New York intellectuals and forged relationships with people such David Reisman, Dwight MacDonald, Irving Howe, and Mary McCarthy. Arendt expressed a continual concern with the nature of political action, the possibility of new beginnings and the idea of the “banality of evil,” introduced in the controversial 1963 book Eichmann in Jerusalem. Difficult to categorize ideologically, Arendt sought a “worldly” politic, rather than politics based in idealism or pragmatism. Her thought influenced post-war thinking on political participation, civil disobedience, race, the Holocaust and the meaning of republicanism and liberalism. King has given us a portrait of a complex, and often ironic, relationship of a seminal thinker with America as a place and a set of ideas and institutions.

To read more about Arendt and America, click here.

In a piece for the Atlantic on the debut of Stephen Colbert’s new late night gig, Megan Garber leverages some scholarship from Pablo Boczkowski’s News at Work: Imitation in an Age of Information Abundance, which positions the thriving competition and rampant imitation prominent among journalists as impetus for our desires to instantly consume—and then avoid acrimonious public conversations about—breaking news (especially that of the political kind). Garber sees Colbert as a song-and-dance Charlie Rose, rather than a David Letterman, and goes on to frame his debut as part of the slow creep of politics into entertainment and entertainment into politics, ultimately noting Boczkowski’s discussion of chatting about politics with our peers.

[P]olitics and late-night comedy have long been happy, if occasionally awkward, bedfellows. Clinton, saxophoning with Arsenio. Bush, chatting with Leno. Obama, chatting with ferns. But Colbert was, in subtle but significant ways, different. He wasn’t treating Jeb as a celebrity, giving him an easy opportunity for free, and content-free, media; he was treating him as a person who is running for political office. He was actually interviewing him. He was trying to have a conversation with him about things that directly affect people’s lives. (Same, to some extent, with George Clooney, Colbert’s first guest: The two talked about acting and movie-making, but they also talked about Darfur.)

You could think of all that as a kind of mission creep, politics seeping into entertainment; you could also, though, think of it as entertainment making its way into politics. Productively. Part of Donald Trump’s popularity has to be explained by his refusal to acknowledge a distinction between the two. And part of why politics has become so polarized, while we’re at it, is likely that we’ve come to see the workings of government as things that exist separately from the rest of our lives. The sociologist Pablo Boczkowski

talks about the reluctance many people have to talk about politics in a work environment, where such discussions can create unnecessary acrimony; instead, we silo ourselves, discussing the issues of the day, for the most part, with people we know will pretty much agree with us.

That’s not a good thing, for people or for democracy. And Colbert’s latest debut suggested that late-night comedy might actually play a role in fixing it.

***

To read more about News at Work, click here.

An excerpt from an exchange between Ta-Nehisi Coates and Jamelle Bouie on Twitter yesterday, in which (among many other things, which each deserve further explication to do justice to their conversation, so check it out in full here) they discuss the relationship between “the submerged state” and race in the United States:

To read more about Suzanne Mettler’s The Submerged State: How Invisible Government Policies Undermine American Democracy, click here.

Edward H. Miller’s Nut Country: Right-Wing Dallas and the Birth of the Southern Strategy explores how a coterie of civic-minded operatives, backroom business brokers, evangelical leaders, and other representatives of the far-right generated a populist movement based on the dollar, the Bible, and an anti-civil rights agenda that would remake the Republican party in their own image, beginning at home in Dallas. Below follows a brief excerpt from a Q & A Miller did recently with the Dallas Morning News. You can read it in full here.

***

In our politics today, what do you hear of the tone that dominated Dallas in the middle of the last century?

I see it echoing throughout the presidential campaign. It’s safe to say that a lot of the incendiary speech has certainly trumped the careful deliberation among the right, and conspiratorial thinking that was long a characteristic of “Nut Country” in the 1950s is very much in vogue today. Donald Trump consistently doubts the legitimacy of President Obama’s birth certificate. The apocalyptic doomsday rhetoric that ultraconservatives like H.L. Hunt, Dan Smoot, W. A. Criswell used is very much part of politics today. This does little to improve our public discourse. When I hear people like Lindsey Graham say he’s running for president because the world is on fire or Glenn Beck mention that the passage of Obamacare means the end of America as we know it, it does remind me of the frenzied style, the over-the-top dialogue that really characterizes the features of the Dallas ultraconservatives.

To read more about Nut Country, click here.

screenshot from AP video of Baltimore protests on April 26, 2015

N. B. D. Connolly, assistant professor of history at Johns Hopkins University and author of A World More Concrete: Real Estate and the Remaking of Jim Crow South Florida, on “Black Culture is Not the Problem” for the New York Times:

The problem is not black culture. It is policy and politics, the very things that bind together the history of Ferguson and Baltimore and, for that matter, the rest of America.

Specifically, the problem rests on the continued profitability of racism. Freddie Gray’s exposure to lead paint as a child, his suspected participation in the drug trade, and the relative confinement of black unrest to black communities during this week’s riot are all features of a city and a country that still segregate people along racial lines, to the financial enrichment of landlords, corner store merchants and other vendors selling second-rate goods.

The problem originates in a political culture that has long bound black bodies to questions of property. Yes, I’m referring to slavery.

To read more about A World More Concrete, click here.

By: Kristi McGuire,

on 4/8/2015

Blog:

The Chicago Blog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Economics,

Sociology,

Author Essays, Interviews, and Excerpts,

Press Releases,

Books for the News,

Politics and Current Events,

Black Studies,

Add a tag

“Can We Race Together? An Autopsy”*

by Ellen Berrey

***

Corporate diversity dialogues are ripe for backlash, the research shows,

even without coffee counter gimmicks.

Corporate executives and university presidents are, yet again, calling for public discussion on race and racial inequality. Revelations about the tech industry’s diversity problem have company officials convening panels on workplace barriers, and, at the University of Oklahoma spokespeople and students are organizing town-hall sessions in response to a fraternity’s racist chant.

The most provocative of the efforts was Starbucks’ failed Race Together program. In March, the company announced that it would ask baristas to initiate dialogues with customers about America’s most vexing dilemma. Although public outcry shut down those conversations before they even got to “Hello,” Starbucks said it would nonetheless carry on Race Together with forums and special USA Today discussion guides. As someone who has done sociological research on diversity initiatives for the past 15 years, I was intrigued.

For a moment, let’s take this seriously

What would conversations about race have looked like if they played out as Starbucks imagined, given the social science of race? Can companies, in Starbucks’ CEO Howard Schultz’s words, “create a more empathetic and inclusive society—one conversation at a time”? A data-driven autopsy of Starbucks’ ambitions is in order.

Surprisingly, Starbucks turned its sights on the provocative issue of racial inequality—not just feel-good cultural differences (or, thank goodness, the sort of “respectability politics” that, under well-intentioned cover, focus on the moral flaws of black people). Most Americans, especially those of us who are white, are ill-informed on the topic of inequality. We generally do not recognize our personal prejudice. We routinely, and incorrectly, insist that we are colorblind and that racism is a thing of the past, as sociologist Eduardo Bonilla-Silva has documented. When we do try to talk about race, we usually resort to what sociologists Joyce Bell and Doug Hartmann call the “happy talk” of diversity, without a language for discussing who comes out ahead and who gets pushed behind.

Starbucks pulls back the veil on our unconscious

How to take this on? Starbucks opted to tackle the thorny issue of unacknowledged prejudice—the cognitive biases that predispose a person against racial minorities and in favor of white people. The company intended to offer “insight into the divisive role unconscious bias plays in our society and the role empathy can play to bridge those divides.” The conversation guide it distributed the first week described a bias experiment in which lawyers were asked to assess an error-ridden memo. When told that the (fictional) author was white, the lawyers commented “has potential.” When told he was black, they remarked “can’t believe he went to NYU.”

Perhaps this was a promising starting point. Americans prefer psychological explanations; we like to think that terrorism, poverty, obesity, and other social ills are rooted in the individual’s psyche.

A comforting thought: I’m not racist

We also do not want to see ourselves as complicit in the segregation of our communities, workplaces, or friendships. We definitely don’t want the stigma of being “racist.” Even white supremacists resist that label. So if it’s true that we can’t see our own bias, as Starbucks told us, we can take comfort in our innocence.

Starbucks’ description of the bias experiment actually took the conversation where it never seems to venture: to the advantages that white people enjoy. White people get help, forgiveness, and the inside track far more often than do people of color. But Starbucks stopped before pointing the finger at who gives white people these advantages.

The rest of Race Together veered off in a confused direction, mostly bent on educated enlightenment. The conversation guide was a mishmash of racial utopianism (the millennials have it figured out!), demography as destiny (immigration changes everything!), triumph over a troublesome past (progress!), testimonies by people of color (the one white guy is clueless!), statistics, inspired introspection, and social network tallies (“I have ____ friends of a different race”!).

Not your daddy’s diversity training

Companies have been trying to positively address race for decades. Typically, they do so through diversity management within their own workforce. Their stated purpose is to increase the numbers of people of color in the top ranks or improve the corporate culture. Most diversity management strategies, however, are far from effective (unless they make someone responsible for results), as shown by as sociologists Alexandra Kalev, Frank Dobbin, and Erin Kelly. Corporate aggrandizement and the façade of legal compliance seem as much the goals as actual change.

Race Together most closely resembled diversity training, which tries to undo managerial stereotyping through educational exchange, but this time the exchange was between capitalists and consumers. And it bucked the typical managerial spin. Usually, the kicker is the business case for diversity: this will boost productivity and profits. Instead, Starbucks made the diversity case for business. Consumption, supposedly, would create inclusion and equity. That would be its own reward. There was no clear connection to its specific business goals, beyond (disgruntled) buzz about the brand.

What were you thinking, Howard Schultz?

Briefly, let’s revisit what made Starbucks’ over-the-counter conversations so offensive. Starbucks was asking low-wage, young, disproportionately minority workers to prompt meaningful exchanges about race with uncaffeinated, mostly white and affluent customers. Even under the best of circumstances, diversity dialogues tend to put the burden of explaining racism on people of color. Here, baristas were supposed to walk the third rail during the morning rush hour without specialized training, much less extra compensation. One sociological term for this is Arlie Hochschild‘s “emotional labor.” The employee was required to tactfully manage customers’ feelings. The most likely reaction from coffee drinkers? Microaggressions of avoidance, denial, and eye-rolling.

The alternative, for Starbucks so-called “partners,” was disgruntled defiance. At my local Starbucks, when I asked about these conversations, the manager emphatically said, “We’re not participating.” The barista next to her was blunt: “We think it’s bullshit.”

Swiftly, the company came out with public statements that had the air of faux intention and cover-up, as if to say, “We’re not retreating; we’re merely advancing in the other direction.” Starbucks had promised a year of Race Together, but the collapse of the café stunt made an all-out retreat more likely: one more forum, one more ad, then silence.

This doesn’t work…

Race Together trod treacherous ground. The research shows that diversity training backfires when it attempts to ferret out prejudice. It puts white people on the defensive and creates a backlash against people of color. For committed consumers, Starbucks was messing with the equivocally best part about capitalism: that you can give someone money and they give you a thing. For activists, this all smelled wrong (i.e., not how you want your latté). Like co-opted social justice.

… Does anyone in HQ ever ask what works?

Starbucks was wise to shift closer to the traditional role of a coffee house—the so-called Third Place between work and home that Schultz has long exalted. Hopefully, the company looks to proven models for productive conversations on race. Organizations such as the Center for Racial Justice Innovation push forward discussions that recognize racism as systemic, not as isolated individual attitudes and bad behaviors. This helps to avoid what people hate most about diversity trainings: forced discourse about superficial differences (“are you a daytime or nighttime person?”) and the wretched hunt for guilty bad guys.

According to social psychologists, unconscious bias can be minimized when people have positive incentives for interpersonal, cross-racial relationships. Wearing a sports jersey for the same team is impressively effective for getting white people to cooperate with African Americans, as shown in a study led by psychologist Jason Nier. The idea is to not provoke white people’s fear and avoidance of doing wrong. It is to motivate people to try to do what’s right by establishing a shared identity

Starbucks also needs to wrestle with its goal of “together.” That’s not always the outcome of conversations about race. Political scientist Katherine Cramer Walsh found that participants in civic dialogues on race commonly walk away with a heightened awareness of their differences, not with the unity that meeting organizers hope to foster.

Is it better to abandon ship?

Despite its missteps, Starbucks, in fact, alit on hopeful insights. Individuals can ignite change, and empathy and listening are starting points. The company deserves some applause for taking the risk and for its deliberate focus on inequality. Undoubtedly, working-class, minority millennials could teach the rest of the country something about race (and executives something about company policy).

The truth hurts

But let’s be clear about what Race Together was not. It was not about addressing institutional discrimination. In that scenario, Starbucks would have issued a press release about eliminating patterns of unfair hiring and firing. It would have overhauled a corporate division of labor that channels racial minorities into lower-tier, nonunionized jobs. It might very well have closed stores in gentrifying neighborhoods.

Those solutions start with incisive diagnosis, not personal reflection. (The U.S. Department of Justice did just that when it scrutinized racial profiling in traffic stops and court fines in Ferguson, Missouri.) Those solutions require change in corporate policy.

To make Race Together honest, Starbucks needed to recognize an ugly truth: America’s race problem is not an inability to talk. It is a failure to rectify the unfair disadvantages hoisted on people of color and the unearned privileges that white people enjoy. Corporations, in their internal operations, are complicit in these very dynamics. So, too, are long-standing government policies, such as tax deductions of home mortgage interest (white folks are far more likely to own their homes). And white Americans may not want to hear it, but racial inequality is, in large measure, rooted in our collective choices: where we’ll pay property taxes, who we’ll tell about a job lead, what we’ll deem criminal, and even when we’ll smile or scowl. Howard Schultz, are you listening?

*This piece was originally published at the Society Pages, http://www.thesocietypages.org

***

Ellen Berrey teaches in the Department of Sociology at the University of Buffalo, SUNY, and is an affiliated scholar of the American Bar Foundation. Her book The Enigma of Diversity: The Language of Race and the Limits of Racial Justice will publish in April 2015.

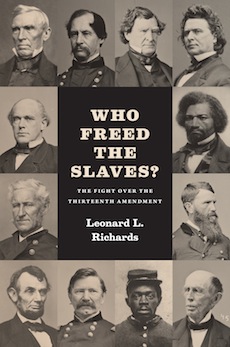

An excerpt from Who Freed the Slaves?: The Fight over the Thirteenth Amendment

by Leonard L. Richards

***

Prologue

WEDNESDAY, JUNE 15, 1864

James Ashley never forgot the moment. After hours of debate, Schuyler Colfax, the Speaker of the House of Representatives, had finally gaveled the 159 House members to take their seats and get ready to vote.

Most of the members were waving a fan of some sort, but none of the fans did much good. Heat and humidity had turned the nation’s capitol into a sauna. Equally bad was the stench that emanated from Washington’s back alleys, nearby swamps, and the twenty-one hospitals in and about the city, which now housed over twenty thousand wounded and dying soldiers. Worse yet was the news from the front lines. According to some reports, the Union army had lost seven thousand men in less than thirty minutes at Cold Harbor. The commanding general, Ulysses S. Grant, had been deemed a “fumbling butcher.”

Nearly everyone around Ashley was impatient, cranky, and miserable. But Ashley was especially downcast. It was his job to get Senate Joint Resolution Number 16, a constitutional amendment to outlaw slavery in the United States, through the House of Representatives, and he didn’t have the votes.

The need for the amendment was obvious. Of the nation’s four million slaves at the outset of the war, no more than five hundred thousand were now free, and, to his disgust, many white Americans intended to have them reenslaved once the war was over. The Supreme Court, moreover, was still in the hands of Chief Justice Roger B. Taney and other staunch proponents of property rights in slaves and state’s rights. If they ever got the chance, they seemed certain not only to strike down much of Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation but also to hold that under the Constitution only the states where slavery existed had the legal power to outlaw it.

Six months earlier, in December 1863, when Ashley and his fellow Republicans had proposed the amendment, he had been more upbeat. He knew that getting the House to abolish slavery, which in his mind was the root cause of the war, was not going to be easy. It required a two-thirds vote. But he had thought that Republicans in both the Senate and the House might somehow muster the necessary two-thirds majority. No longer did they have to worry about the united opposition of fifteen slave states. Eleven of the fifteen were out of the Union, including South Carolina and Mississippi, the two with the highest percentage of slaves, and Virginia, the one with the largest House delegation. In addition, the war was in its thirty-third month. Hundreds of thousands of Northern men had been killed on the battlefield. The one-day bloodbath at Antietam was now etched into the memory of every one of his Toledo constituents as well as every member of Congress. So, too, was the three-day battle at Gettysburg.

If Republicans held firm, all they needed to push the amendment through the House was a handful of votes from their opponents, either from the border slave state representatives who had remained in the Union or from free state Democrats. It was his job to get those votes. He was the bill’s floor manager.

Back in December, Ashley had been the first House member to propose such an amendment. Although few of his colleagues realized it, he had been toying with the idea for nearly a decade. He had made a similar proposal in September 1856, when it didn’t have a chance of passing.

He was a political novice at the time, just twenty-nine years old, and known mainly for being big and burly, six feet tall and starting to spread around the middle, with a wild mane of curly hair and a loud, resonating voice. He had just gotten established in Toledo politics. He had moved there three years earlier from the town of Portsmouth, in southern Ohio, largely because he had just gotten married and was in deep trouble for helping slaves flee across the Ohio River. He was not yet a Congressman. Nor was he running for office. He was just campaigning for the Republican Party’s first presidential candidate, John C. Frémont, and Richard Mott, a House member who was up for reelection. In doing so, he gave a stump speech at a grove near Montpelier, Ohio.

James M. Ashley, congressman from Ohio. Brady-Handy Photograph Collection, Library of Congress (lC-Bh824-5303).

The speech lasted two hours. In most respects, it was a typical Republican stump speech. It was mainly a collection of stories, many from his youth, living and working along the Ohio River. Running through it were several themes that tied the stories together and foreshadowed the rest of his career. In touting the two candidates, he blamed the nation’s troubles on a conspiracy of slaveholders and Northern men with Southern principles, or as he called them “slave barons” and “doughfaces.” These men, he claimed, had deliberately misconstrued the Bible, misinterpreted the Constitution, and gained complete control of the federal government. “For nearly half a century,” he told his listeners, some two hundred thousand slave barons had “ruled the nation, morally and politically, including a majority of the Northern States, with a rod of iron.” And before “the advancing march of these slave barons,” the “great body of Northern public men” had “bowed down . . . with their hands on their mouths and mouths in the dust, with an abasement as servile as that of a vanquished, spiritless people, before their conquerors.”

Across the North, many Republican spokesmen were saying much the same thing. What made Ashley’s speech unusual was that he made no attempt to hide his radicalism. He made it clear to the crowd at Montpelier that he would do almost anything to destroy slavery and the men who profited from it. He had learned to hate slavery and the slave barons during his boyhood, traveling with his father, a Campbellite preacher, through Kentucky and western Virginia, and later working as a cabin boy on the Ohio River. Never would he forget how traumatized he had been as a nine-year-old seeing for the first time slaves in chains being driven down a road to the Deep South, whipping posts on which black men had been beaten, and boys his own age being sold away from their mothers. Nor would he ever forget the white man who wouldn’t let his cattle drink from a stream in which his father was baptizing slaves. How, he had wondered, could his father still justify slavery? Certainly, it didn’t square with the teachings of Christ or what his mother was teaching him back home.

Ashley also made it clear to the crowd at Montpelier that he had violated the Fugitive Slave Law more times than he could count. He had actually begun helping slaves flee bondage in 1839, when he was just fifteen years old, and he had continued doing so after the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 made the penalties much stiffer. To avoid prosecution, he and his wife had fled southern Ohio in 1851. Would he now mend his ways? “Never!” he told his audience. The law was a gross violation of the teachings of Christ, and for that reason he had never obeyed it and with “God’s help . . . never shall.”

What, then, should his listeners do? The first step was to join him in supporting John C. Frémont for president and Richard Mott for another term in Congress. Another was to join him in never obeying the “infamous fugitive-slave law”—the most “unholy” of the laws that these slave barons and their Northern sycophants had passed. And perhaps still another, he suggested, was to join him in pushing for a constitutional amendment outlawing “the crime of American slavery” if that should become “necessary.”

The last suggestion, in 1856, was clearly fanciful. Nearly half the states were slave states. Thus getting two-thirds of the House, much less two-thirds of the Senate, to support an amendment outlawing slavery was next to impossible. Ashley knew that. Perhaps some in his audience, especially those who cheered the loudest, thought otherwise. But not Ashley. Although still a political neophyte, he knew the rules of the game. He was also good with numbers, always had been, and always would be. Nonetheless, he told his audience to put it on their “to do” list.

Five years later, in December 1861, Ashley added to the list. By then he was no longer a political neophyte. He had been twice elected to Congress. Eleven states had seceded from the Union, and the Civil War was in its eighth month. As chairman of the House Committee on Territories, he proposed that the eleven states no longer be treated as states. Instead they should be treated as “territories” under the control of Congress, and Congress should impose on them certain conditions before they were allowed to regain statehood. More specifically, Congress should abolish slavery in these territories, confiscate all rebel lands, distribute the confiscated lands in plots of 160 acres or fewer to loyal citizens of any color, disfranchise the rebel leaders, and establish new governments with universal adult male suffrage. Did that mean, asked one skeptic, that black men were to receive land? And the right to vote? Yes, it did. And if such measures were enacted, said Ashley, he felt certain that the slave barons would be forever stripped of their power.

Ashley’s goal was clear. The 1850 census, from which Ashley and most Republicans drew their numbers, had indicated that just a few Southern families had the lion’s share of the South’s wealth. Especially potent were the truly big slaveholders—families with over one hundred slaves. There were 105 such family heads in Virginia, 181 in Georgia, 279 in Mississippi, 312 in Alabama, 363 in South Carolina, and 460 in Louisiana. With respect to landholdings, there were 371 family heads in Louisiana with more than one thousand acres, 481 in Mississippi, 482 in South Carolina, 641 in Virginia, 696 in Alabama, and 902 in Georgia.

In Ashley’s view, virtually all these wealth holders were rebels, and the Congress should go after all their assets. Strip them of their slaves. Strip them of their land. Strip them of their right to hold office. Halfhearted measures, he contended, would lead only to half-hearted results. Taking away a slave baron’s slaves undoubtedly would hobble him, but it wouldn’t destroy him. With his vast landholdings, he would soon be back in power. And with the right to hold office, he would not only have economic power but also political power. And with the end of the three-fifths clause, the clause in the Constitution that counted slaves as only three-fifths of a free person when it came to tabulating seats in Congress and electoral votes, the South would have more power than ever before.

When Ashley made this proposal in December 1861, everyone on his committee told him it was much too radical ever to get through Congress. He knew that. But he also knew that there were men in Congress who agreed with him, including four of the seven men on his committee, several dozen in the House, maybe a half-dozen in the Senate, and even some notables such as Representative Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania and Senator Ben Wade of Ohio.

The trouble was the opposition. It was formidable. Not only did it include the “Peace” Democrats, men who seemingly wanted peace at any price, men whom Ashley regarded as traitors, but also “War” Democrats, men such as General George McClellan, General Don Carlos Buell, and General Henry Halleck, men who were leading the nation’s troops. Also certain to oppose him were the border state Unionists, especially the Kentuckians, and most important of all, Abraham Lincoln. Against such opposition, all Ashley and the other radicals could do was push, prod, and hope to get maybe a piece or two of the total package enacted.

Two years later, in December 1863, Ashley thought it was indeed “necessary” to strike a deathblow against slavery. He also thought it was possible to get a few pieces of his 1861 package into law. So, just after the House opened for its winter session, he introduced two measures. One was a reconstruction bill that followed, at least at first glance, what Lincoln had called for in his annual message. Like Lincoln, Ashley proposed that a seceded state be let back into the Union when only 10 percent of its 1860 voters took an oath of loyalty.

Had he suddenly become a moderate? A conservative? Not quite. To Lincoln’s famous 10 percent plan, Ashley added two provisions. One would take away the right to vote and to hold office from all those who had fought against the Union or held an office in a rebel state. That was a significant chunk of the population. The other would give the right to vote to all adult black males. That was even a bigger chunk of the population, especially in South Carolina and Mississippi.

The other measure that Ashley proposed that December was the constitutional amendment that outlawed slavery. A few days later, Representative James F. Wilson of Iowa made a similar proposal. The wording differed, but the intent was the same. The Constitution had to be amended, contended Wilson, not only to eradicate slavery but also to stop slaveholders and their supporters from launching a program of reenslavement once the war was over. Then, several weeks later, Senator John Henderson of Missouri and Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts introduced similar amendments. Sumner’s was the more radical. The Massachusetts senator not only wanted to end slavery. He also wanted to end racial inequality.

The Senate Judiciary Committee then took charge. They ignored Sumner’s cry for racial justice and worked out the bill’s final language. The wording was clear and simple: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime, whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

On April 8, 1864, the committee’s wording came before the Senate for a final vote. Although a few empty seats could be found in the men’s gallery, the women’s gallery was packed, mainly by church women who had organized a massive petition drive calling on Congress to abolish slavery. Congress for the most part had ignored their hard work. But to the women’s delight, thirty-eight senators now voted for the amendment, six against, giving the proposed amendment eight votes more than what was needed to meet the two-thirds requirement.

All thirty Republicans in attendance voted aye. The no votes came from two free state Democrats, Thomas A. Hendricks of Indiana and James McDougall of California, and four slave state senators: Garrett Davis and Lazarus W. Powell of Kentucky and George R. Riddle and Willard Saulsbury of Delaware. Especially irate was Saulsbury. A strong proponent of reenslavement, he made sure that the women knew that he regarded them with contempt. In a booming voice, he told them on leaving the Senate floor that all was lost and that there was no longer any chance of ever restoring the eleven Confederate states to the Union.

Now, nine weeks later, the measure was before the House. And its floor manager, James Ashley, expected the worst. He kept a close count. And, as the members voted, he realized that he was well short of the required two-thirds. Of the eighty Republicans who were in attendance, seventy-nine eventually cast aye votes and one abstained. Of the seventeen slave state representatives in attendance, eleven voted aye and six nay. But of the sixty-two free state Democrats, only four voted for the amendment while fifty-eight voted nay. As a result, the final vote was going to be ninety-four to sixty-four. That was eleven shy of the necessary two-thirds majority.

The outcome was even worse than Ashley had anticipated. “Educated in the political school of Jefferson,” he later recalled, “I was absolutely amazed at the solid Democratic vote against the amendment on the 15th of June. To me it looked as if the golden hour had come, when the Democratic party could, without apology, and without regret, emancipate itself from the fatal dogmas of Calhoun, and reaffirm the doctrines of Jefferson. It had always seemed to me that the great men in the Democratic party had shown a broader spirit in favor of human liberty than their political opponents, and until the domination of Mr. Calhoun and his States-rights disciples, this was undoubtedly true.”

Despite the solid Democratic vote against the resolution, there was still one way that Ashley could save the amendment from certain congressional death. And that was to take advantage of a House rule that allowed a member to bring a defeated measure up for reconsideration if he intended to change his vote. To make use of this rule, however, Ashley had to change his vote before the clerk announced the final tally. He had voted aye along with his fellow Republicans. He now had to get into the “no” column. That he did. The final vote thus became ninety-three to sixty-five.

Two weeks later, Representative William Steele Holman, Democrat of Indiana, asked Ashley when he planned to call for reconsideration. Ashley told him not now but maybe after the next election. The trick, he said, was to find enough men in Holman’s party who were “naturally inclined to favor the amendment, and strong enough to meet and repel the fierce partisan attack which were certain to be made upon them.”

Holman, Ashley knew, would not be one of them. Although the Indiana Democrat had once been a staunch supporter of the war effort, he opposed the destruction of slavery. Not only had he just voted against the amendment—he had vehemently denounced it. Holman, as Ashley viewed him, was thus one of the “devil’s disciples.” He was beyond redemption. And with this in mind, Ashley set about to find at least eleven additional House members who would stand their ground against men like Holman.

To read more about Who Freed the Slaves?, click here.

Excerpted from

How Many is Too Many?: The Progressive Argument for Reducing Immigration into the United States

by Philip Cafaro

***

How many immigrants should we allow into the United States annually, and who gets to come?

The question is easy to state but hard to answer, for thoughtful individuals and for our nation as a whole. It is a complex question, touching on issues of race and class, morals and money, power and political allegiance. It is an important question, since our answer will help determine what kind of country our children and grandchildren inherit. It is a contentious question: answer it wrongly and you may hear some choice personal epithets directed your way, depending on who you are talking to. It is also an endlessly recurring question, since conditions will change, and an immigration policy that made sense in one era may no longer work in another. Any answer we give must be open to revision.

This book explores the immigration question in light of current realities and defends one provisional answer to it. By exploring the question from a variety of angles and making my own political beliefs explicit, I hope that it will help readers come to their own well-informed conclusions. Our answers may differ, but as fellow citizens we need to keep talking to one another and try to come up with immigration policies that further the common good.

Why are immigration debates frequently so angry? People on one side often seem to assume it is just because people on the other are stupid, or immoral. I disagree. Immigration is contentious because vital interests are at stake and no one set of policies can fully accommodate all of them. Consider two stories from among the hundreds I’ve heard while researching this book.

* * *

It is lunchtime on a sunny October day and I’m talking to Javier, an electrician’s assistant, at a home construction site in Longmont, Colorado, near Denver. He is short and solidly built; his words are soft-spoken but clear. Although he apologizes for his English, it is quite good. At any rate much better than my Spanish.

Javier studied to be an electrician in Mexico, but could not find work there after school. “You have to pay to work,” he explains: pay corrupt officials up to two years’ wages up front just to start a job. “Too much corruption,” he says, a refrain I find repeated often by Mexican immigrants. They feel that a poor man cannot get ahead there, can hardly get started.

So in 1989 Javier came to the United States, undocumented, working various jobs in food preparation and construction. He has lived in Colorado for nine years and now has a wife (also here illegally) and two girls, ages seven and three. “I like USA, you have a better life here,” he says. Of course he misses his family back in Mexico. But to his father’s entreaties to come home, he explains that he needs to consider his own family now. Javier told me that he’s not looking to get rich, he just wants a decent life for himself and his girls. Who could blame him?

Ironically one of the things Javier likes most about the United States is that we have rules that are fairly enforced. Unlike in Mexico, a poor man does not live at the whim of corrupt officials. When I suggest that Mexico might need more people like him to stay and fight “corruption,” he just laughs. “No, go to jail,c he says, or worse. Like the dozens of other Mexican and Central American immigrants I have interviewed for this book, Javier does not seem to think that such corruption could ever change in the land of his birth.

Do immigrants take jobs away from Americans? I ask. “American people no want to work in the fields,” he responds, or as dishwashers in restaurants. Still, he continues, “the problem is cheap labor.” Too many immigrants coming into construction lowers wages for everyone— including other immigrants like himself.

“The American people say, all Mexicans the same,” Javier says. He does not want to be lumped together with “all Mexicans,” or labeled a problem, but judged for who he is as an individual. “I don’t like it when my people abandon cars, or steal.” If immigrants commit crimes, he thinks they should go to jail, or be deported. But “that no me.” While many immigrants work under the table for cash, he is proud of the fact that he pays his taxes. Proud, too, that he gives a good day’s work for his daily pay (a fact confirmed by his coworkers).

Javier’s boss, Andy, thinks that immigration levels are too high and that too many people flout the law and work illegally. He was disappointed, he says, to find out several years ago that Javier was in the country illegally. Still he likes and respects Javier and worries about his family. He is trying to help him get legal residency.

With the government showing new initiative in immigration enforcement—including a well-publicized raid at a nearby meat-packing plant that caught hundreds of illegal workers—there is a lot of worry among undocumented immigrants. “Everyone scared now,” Javier says. He and his wife used to go to restaurants or stores without a second thought; now they are sometimes afraid to go out. “It’s hard,” he says. But: “I understand. If the people say, ‘All the people here, go back to Mexico,’ I understand.”

Javier’s answer to one of my standard questions—“How might changes in immigration policy affect you?”—is obvious. Tighter enforcement could break up his family and destroy the life he has created here in America. An amnesty would give him a chance to regularize his life. “Sometimes,” he says, “I dream in my heart, ‘If you no want to give me paper for residence, or whatever, just give me permit for work.’ ”

* * *

It’s a few months later and I’m back in Longmont, eating a 6:30 breakfast at a café out by the Interstate with Tom Kenney. Fit and alert, Tom looks to be in his mid-forties. Born and raised in Denver, he has been spraying custom finishes on drywall for twenty-five years and has had his own company since 1989. “At one point we had twelve people running three trucks,” he says. Now his business is just him and his wife. “Things have changed,” he says.

Although it has cooled off considerably, residential and commercial construction was booming when I interviewed Tom. The main “thing that’s changed” is the number of immigrants in construction. When Tom got into it twenty-five years ago, construction used almost all native-born workers. Today estimates of the number of immigrant workers in northern Colorado range from 50% to 70% of the total construction workforce. Some trades, like pouring concrete and framing, use immigrant labor almost exclusively. Come in with an “all-white” crew of framers, another small contractor tells me, and people do a double-take.

Tom is an independent contractor, bidding on individual jobs. But, he says, “guys are coming in with bids that are impossible.” After all his time in the business, “no way they can be as efficient in time and materials as me.” The difference has to be in the cost of labor. “They’re not paying the taxes and insurance that I am,” he says. Insurance, workmen’s compensation, and taxes add about 40% to the cost of legally employed workers. When you add the lower wages that immigrants are often willing to take, there is plenty of opportunity for competing contractors to underbid Tom and still make a tidy profit. He no longer bids on the big new construction projects and jobs in individual, custom-built houses are becoming harder to find.

“I’ve gone in to spray a house and there’s a guy sleeping in the bathtub, with a microwave set up in the kitchen. I’m thinking, ‘You moved into this house for two weeks to hang and paint it, you’re gonna get cash from somebody, and he’s gonna pick you up and drive you to the next one.’ ” He seems more upset at the contractor than at the undocumented worker who labors for him.

In this way, some trades in construction are turning into the equivalent of migrant labor in agriculture. Workers do not have insurance or workmen’s compensation, so if they are hurt or worn out on the job, they are simply discarded and replaced. Workers are used up, while the builders and contractors higher up the food chain keep more of the profits for themselves. “The quality of life [for construction workers] has changed drastically,” says Tom. “I don’t want to live like that. I want to go home and live with my family.”

Do immigrants perform jobs Americans don’t want to do? I ask. The answer is no. “My job is undesirable,” Tom replies. “It’s dirty, it’s messy, it’s dusty. I learned right away that because of that, the opportunity is available to make money in it. That job has served me well”—at least up until recently. He now travels as far away as Wyoming and southern Colorado to find work. “We’re all fighting for scraps right now.”

Over the years, Tom has built a reputation for quality work and efficient and prompt service, as I confirmed in interviews with others in the business. Until recently that was enough to secure a good living. Now though, like a friend of his who recently folded his small landscaping company (“I just can’t bid ’em low enough”), Tom is thinking of leaving the business. He is also struggling to find a way to keep up the mortgage payments on his house.

He does not blame immigrants, though. “If you were born in Mexico, and you had to fight for food or clothing, you would do the same thing,” Tom tells me. “You would come here.”

* * *

Any immigration policy will have winners and losers. So claims Harvard economist George Borjas, a leading authority on the economic impacts of immigration. My interviews with Javier Morales and Tom Kenney suggest why Borjas is right.

If we enforce our immigration laws, then good people like Javier and his family will have their lives turned upside down. If we limit the numbers of immigrants, then good people in Mexico (and Guatemala, and Vietnam, and the Philippines …) will have to forgo opportunities to live better lives in the United States.

On the other hand, if we fail to enforce our immigration laws or repeatedly grant amnesties to people like Javier who are in the country illegally, then we forfeit the ability to set limits to immigration. And if immigration levels remain high, then hard-working men and women like Tom and his wife and children will probably continue to see their economic fortunes decline. Economic inequality will continue to increase in America, as it has for the past four decades.

In the abstract neither of these options is appealing. When you talk to the people most directly affected by our immigration policies, the dilemma becomes even more acute. But as we will see further on when we explore the economics of immigration in greater detail, these appear to be the options we have.

Recognizing trade-offs—economic, environmental, social—is indeed the beginning of wisdom on the topic of immigration. We should not exaggerate such conflicts, or imagine conflicts where none exist, but neither can we ignore them. Here are some other trade-offs that immigration decisions may force us to confront:

- Cheaper prices for new houses vs. good wages for construction workers.

- Accommodating more people in the United States vs. preserving wildlife habitat and vital resources.

- Increasing ethnic and racial diversity in America vs. enhancing social solidarity among our citizens.

- More opportunities for Latin Americans to work in the United States vs. greater pressure on Latin American elites to share wealth and opportunities with their fellow citizens.

The best approach to immigration will make such trade-offs explicit, minimize them where possible, and choose fairly between them when necessary.

Since any immigration policy will have winners and losers, at any particular time there probably will be reasonable arguments for changing the mix of immigrants we allow in, or for increasing or decreasing overall immigration, with good people on all sides of these issues. Whatever your current beliefs, by the time you finish this book you should have a much better understanding of the complex trade-offs involved in setting immigration policy. This may cause you to change your views about immigration. It may throw your current views into doubt, making it harder to choose a position on how many immigrants to let into the country each year; or what to do about illegal immigrants; or whether we should emphasize country of origin, educational level, family reunification, or asylum and refugee claims, in choosing whom to let in. In the end, understanding trade-offs ensures that whatever policies we wind up advocating for are more consciously chosen, rationally defensible, and honest. For such a contentious issue, where debate often generates more heat than light, that might have to suffice.

* * *

Perhaps a few words about my own political orientation will help clarify the argument and goals of this book. I’m a political progressive. I favor a relatively equal distribution of wealth across society, economic security for workers and their families, strong, well-enforced environmental protection laws, and an end to racial discrimination in the United States. I want to maximize the political power of common citizens and limit the influence of large corporations. Among my political heroes are the three Roosevelts (Teddy, Franklin, and Eleanor), Rachel Carson, and Martin Luther King Jr.

I also want to reduce immigration into the United States. If this combination seems odd to you, you are not alone. Friends, political allies, even my mother the social worker shake their heads or worse when I bring up the subject. This book aims to show that this combination of political progressivism and reduced immigration is not odd at all. In fact, it makes more sense than liberals’ typical embrace of mass immigration: an embrace shared by many conservatives, from George W. Bush and Orrin Hatch to the editorial board of the Wall Street Journal and the US Chamber of Commerce.

In what follows I detail how current immigration levels—the highest in American history—undermine attempts to achieve progressive economic, environmental, and social goals. I have tried not to oversimplify these complex issues, or mislead readers by cherry-picking facts to support pre-established conclusions. I have worked hard to present the experts’ views on how immigration affects US population growth, poorer workers’ wages, urban sprawl, and so forth. Where the facts are unclear or knowledgeable observers disagree, I report that, too.