The human brain is a most wonderful organ: it is our window on time. Our brains have specialized structures that work together to give us our human sense of time. The temporal lobe helps form long term memories, without which we would not be aware of the past, whilst the frontal lobe allows us to plan for the future.

The post Time and perception appeared first on OUPblog.

Albert Einstein’s greatest achievement, the general theory of relativity, was announced by him exactly a century ago, in a series of four papers read to the Prussian Academy of Sciences in Berlin in November 1915, during the turmoil of the First World War. For many years, hardly any physicist—let alone any other type of scientist—could understand it.

The post Einstein’s mysterious genius appeared first on OUPblog.

November 2015 marks the 100th anniversary of Albert Einstein's general theory of relativity. This theory is one of many pivotal scientific discoveries that would drastically influence our understanding of the world around us.

The post How and why are scientific theories accepted? appeared first on OUPblog.

Some of the most beguiling writing for adults features young characters. I touched on this when I reviewed Joan London’s The Golden Age in January. http://blog.boomerangbooks.com.au/the-golden-age-where-children-are-gold/2015/01 This book has recently been awarded the 2015 Kibble Award. Yann Martel’s The Life of Pi also has a young adult protagonist, as does Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch and Eimear […]

The science and even the popular press are filled with excitement at the moment after the OPERA experiment at Europe’s giant particle physics laboratory, CERN (to which I applied for a summer job when I was 16, but that’s another story). Apparently, neutrinos sent from CERN and captured at Italy’s INFN Gran Sasso Laboratory about 730 km away are arriving faster than scientists thought physically possible – faster than the speed of light travelling in a vacuum.

The science and even the popular press are filled with excitement at the moment after the OPERA experiment at Europe’s giant particle physics laboratory, CERN (to which I applied for a summer job when I was 16, but that’s another story). Apparently, neutrinos sent from CERN and captured at Italy’s INFN Gran Sasso Laboratory about 730 km away are arriving faster than scientists thought physically possible – faster than the speed of light travelling in a vacuum.

I had to write about this because the news reporting has really annoyed me. Every announcement has said that Einstein might be wrong because he (special relativity) says nothing can travel faster than light in a vacuum. Poppycock! (As I’m being polite.) What the theory says is that nothing that has what scientists call “rest mass” can travel at the speed of light – there isn’t any block on things travelling faster. It’s always slightly surprised me that in a discipline where mathematical physicists are used to things called discontinuous functions, I rarely hear of people willing to accept that something could go from “slower” to “faster” without having to “equal”, but it might be possible.

I had to write about this because the news reporting has really annoyed me. Every announcement has said that Einstein might be wrong because he (special relativity) says nothing can travel faster than light in a vacuum. Poppycock! (As I’m being polite.) What the theory says is that nothing that has what scientists call “rest mass” can travel at the speed of light – there isn’t any block on things travelling faster. It’s always slightly surprised me that in a discipline where mathematical physicists are used to things called discontinuous functions, I rarely hear of people willing to accept that something could go from “slower” to “faster” without having to “equal”, but it might be possible.

One argument against travelling faster than light is that, although there are solutions to Einstein’s equations, they contain the square root of minus one which we sometimes call an “imaginary” number (as opposed to other numbers that are called “real”). This is a brilliant example of mathematical spin and how it has actually damaged our understanding of mathematics and the universe. There is nothing less real about these imaginary numbers than what are called the real ones. It’s actually by combining both set that we achieve a far deeper understanding of the mathematical and physical universe. But way back when they were first introduced, French mathematician and philosopher Rene Decartes was very distrustful of them so coined the term imaginary as a pejorative description, hoping it would mean they didn’t catch on. He’s got a lot to answer for.

What is a neutrino? Like the similarly named neutron, a neutrino carries no net electric charge (compared with other familiar subatomic particles such as electrons (-1) or protons (+1). Unlike the neutron, the neutrino has almost (but not quite) no mass. Having no charge and almost no mass makes a neutrino extremely difficult to detect.

Back to relativity! Anything travelling faster than light in relativity yields solutions including the square root of minus one which people have interpreted as meaning travelling backwards in time. That’s the reason for the joke that’s currently doing the rounds on the twittersphere:

Barman: “I’m sorry, sir. We don’t serve neutrinos in here.”

A neutrino walks into a bar.

By Jim Baggott

If a tree falls in the forest, and there’s nobody around to hear, does it make a sound?

For centuries philosophers have been teasing our intellects with such questions. Of course, the answer depends on how we choose to interpret the use of the word ‘sound’. If by sound we mean compressions and rarefactions in the air which result from the physical disturbances caused by the falling tree and which propagate through the air with audio frequencies, then we might not hesitate to answer in the affirmative.

Here the word ‘sound’ is used to describe a physical phenomenon – the wave disturbance. But sound is also a human experience, the result of physical signals delivered by human sense organs which are synthesized in the mind as a form of perception.

Now, to a large extent, we can interpret the actions of human sense organs in much the same way we interpret mechanical measuring devices. The human auditory apparatus simply translates one set of physical phenomena into another, leading eventually to stimulation of those parts of the brain cortex responsible for the perception of sound. It is here that the distinction comes. Everything to this point is explicable in terms of physics and chemistry, but the process by which we turn electrical signals in the brain into human perception and experience in the mind remains, at present, unfathomable.

Philosophers have long argued that sound, colour, taste, smell and touch are all secondary qualities which exist only in our minds. We have no basis for our common-sense assumption that these secondary qualities reflect or represent reality as it really is. So, if we interpret the word ‘sound’ to mean a human experience rather than a physical phenomenon, then when there is nobody around there is a sense in which the falling tree makes no sound at all.

This business about the distinction between ‘things-in-themselves’ and ‘things-as-they-appear’ has troubled philosophers for as long as the subject has existed, but what does it have to do with modern physics, specifically the story of quantum theory? In fact, such questions have dogged the theory almost from the moment of its inception in the 1920s. Ever since it was discovered that atomic and sub-atomic particles exhibit both localised, particle-like properties and delocalised, wave-like properties physicists have become ravelled in a debate about what we can and can’t know about the ‘true’ nature of physical reality.

Albert Einstein once famously declared that God does not play dice. In essence, a quantum particle such as an electron may be described in terms of a delocalized ‘wavefunction’, with probabilities for appearing ‘here’ or ‘there’. When we look to see where the electron actually is, the wavefunction is said to ‘collapse’ instantaneously, and appears ‘here’ with a frequency consistent with the probability predicted by quantum theory. But there is no predicting precisely where an individual electron will be found. Chance is inherent in the collapse of the wavefunction, and it was this feature of quantum theory that got Einstein so upset. To make matters worse, if the collapse is instantaneous then this implies what Einstein called a ‘spooky action-at-a-distance’ which, he argued, appeared to violate a key postulate of his own special theory of relativity.

So what evidence do we have for this mysterious collapse of the wavefunction? Well, none actually. We postulate the collapse in an attempt to explain how a quantum system with many different possible outcomes before measurement transforms into a system with one and only one result after measurement. To Irish physicist John Bell this seemed to be at best a confidence-trick, at worst a fraud. ‘A theory founded in this way on arguments of manifestly approximate character,’ he wrote some years later, ‘howe

By definition, the Universe is a pretty big place, so the questions we ask about it tend to produce suitably mind-boggling answers. That’s one of the reasons why astronomy and cosmology can be such fascinating subjects.

Stuart Clark, author of The Sun Kings, has just published a new book in the Quercus Big Questions series called “The Universe”. Last Wednesday, he gave a talk on those same questions to a packed audience at the University of Hertfordshire. It was so popular that nearly a hundred people had to be turned away. I’m disappointed for them, but thrilled that popular science and, especially, astronomy, has really caught the public’s imagination.

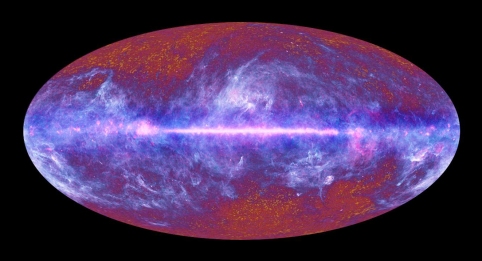

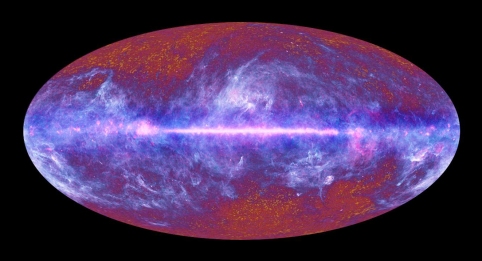

The book covers twenty questions you might want to ask about the Universe, beginning with “What is it?” and going all the way through to asking “If it had a creator”. I didn’t expect Stuart to be able to cover everything in between in an hour and a quarter, but he managed the contents list impressively. Especially when he began by showing this image from the European Space Agency’s (ESA’s) Planck observatory/telescope and saying that here is everything that is, that ever was and that ever will be.

The first thing to say is that there were more questions than answers. It was refreshing to hear a scientist speak with such an open mind, without claiming that all the major debates are settled. The talk flowed very well, and some of the questions covered were:

What is the Universe?

How old is the Universe?

How did the Universe form?

What were the first celestial objects?

Can we travel through time and space?

What are black holes?

What is dark energy?

How will the Universe end?

Stuart didn’t talk about the aspects of relativity theory that allow time travel into the future, instead showing a representation of the Alcubierre Drive that, theoretically, could allow for faster than light travel, surfing a self-generated wave of antigravity. Personally, I found the discussion on the very first celestial objects the most thought-provoking. Afterwards we went for a beer in a local Hatfield pub and the conversation moved onto the astronomically connected music of Canadian rockers Rush, with songs such as Cygnus X1 (the first black hole candidate to be discovered) and Natural Science.

Stuart didn’t talk about the aspects of relativity theory that allow time travel into the future, instead showing a representation of the Alcubierre Drive that, theoretically, could allow for faster than light travel, surfing a self-generated wave of antigravity. Personally, I found the discussion on the very first celestial objects the most thought-provoking. Afterwards we went for a beer in a local Hatfield pub and the conversation moved onto the astronomically connected music of Canadian rockers Rush, with songs such as Cygnus X1 (the first black hole candidate to be discovered) and Natural Science.

If anyone has a q

The science and even the popular press are filled with excitement at the moment after the

The science and even the popular press are filled with excitement at the moment after the

This is the continuation of the story about the origin of the Germanic word for man. Last week I left off after expressing great doubts about the protoform that connected man and guma and tried to defend the Indo-European girl from an unpronounceable name. As could be expected, in their attempts to discover the origin of man etymologists cast a wide net for words containing m and n.

The post You’ll be a man, my son. Part 2 appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford is thrilled to welcome Dr. Kathy Battista as the new Editor in Chief of the Benezit Dictionary of Artists. Get to know Dr. Battista with our Q/A session.

The post Meet Dr. Kathy Battista, Benezit’s new Editor in Chief appeared first on OUPblog.