By Joy Hakim

Surprisingly, in a country that cares about its founding history, few Americans know of Thomas Jefferson’s Statute for Religious Freedom, a document that Harvard’s distinguished (emeritus) history professor, Bernard Bailyn called, “the most important document in American history, bar none.”

Yet that document is not found in most school standards, so it’s rarely taught. How come? Maybe because it is a Virginia document, passed by Virginia’s General Assembly. Or maybe because its ideas found their way directly into the Constitution’s First Amendment and that seems enough for most Americans.

Why do Bailyn and some others think it so important? Because it was radical, trailblazing, and uniquely American: no government before had ever taken the astonishing stand that it takes. In essence it says that religious belief is a personal thing, a matter of heart and soul, and that government has no right to meddle with beliefs, or tax citizens to support churches they may disavow. That wasn’t the way governments were expected to operate.

Imagine you live in 18th century Virginia: According to a law on the books you have to go to church—every day–usually for both morning and evening prayer. If you don’t go you could be whipped, sentenced to work on an oceangoing galley, or worse. And you don’t have a choice of churches. In Virginia the established church is Anglican. That means you are assessed taxes to support that church whether you believed in it or not. You couldn’t be a member of the legislature unless you are a member of the Established Church. So the legislation of the House of Burgesses reflect the world of its Anglican delegates.

But the colonies are home to independent folk who braved a turbulent ocean to be able to think for themselves. Roger Williams, kicked out of Puritan Massachusetts, talks of “freedom of conscience” and lets anyone who wishes settle in the colony he founds on Rhode Island. The Long Island town of Flushing has a charter that promises settlers freedom of conscience, so leaders there petition New York Governor Peter Stuyvesant concerning the public torturing of Quaker preacher Robert Hodgson. In the Flushing Remonstrance they write, “We desire in this case not to judge lest we be judged.” In Virginia, Jemmy Madison stands outside the Orange County jail and listens as a Methodist preacher, behind bars, spreads the word of the Gospel. Why are Methodists, Baptists and Presbyterians being put in jail, Madison asks?

In 1777 Jefferson writes the eloquent Statute for Religious Freedom, introducing it into the legislature in 1779. This is a Revolutionary time and England’s church has to go. Will an established American church succeed it?

Patrick Henry, popular and powerful, introduces a bill that seems enlightened: it calls for public assessments to support all Christian worship. James Madison counters in his remarkable Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments, arguing the case for full religious freedom. Most legislators are perplexed. Every nation has its state church. George Washington is on the fence. If citizens are not forced to go to church will they sink into immorality? What is the role of government?

John Locke has written a famous letter on religious tolerance, but Jefferson and Madison are clear: this statute is not about tolerance, it is about full acceptance — and jurisdiction. Jefferson’s point is that governments have no business telling people what they should believe. In his Notes on Virginia he says,

“The legitimate powers of government extend to such acts only as are injurious to others. But it does me no injury for my neighbor to say there are twenty gods or one god. It neither picks my pocket nor breaks my leg. […] To suffer the civil magistrate to intrude his powers into the field of opinion. . .is a dangerous fallacy, which at once destroys all religious liberty.”

Meanwhile Patrick Henry’s bill passes its first two readings. A third and it becomes law. Jefferson writes to Madison from Paris where he is ambassador, “What we have to do is devotedly pray for his death.” (He’s talking about Henry.) Madison takes a pragmatic path. He gets Patrick Henry kicked upstairs into the governor’s chair, where he has no vote. Then he reintroduces Jefferson’s bill for establishing religious freedom. It finally passes, on 16 January 1786.

It turns out that Virginians are no more, nor less, moral than they were when they were forced to go to church. George Washington becomes one of the biggest fans of the idea of religious freedom. In a famous letter to the Hebrew Congregation in Newport Rhode Island, he says,

“The citizens of the United States of America have a right to applaud themselves for having given to mankind examples of an enlarged and liberal policy–a policy worthy of imitation. . .It is now no more that toleration is spoken of as if it were the indulgence of one class of people that another enjoyed the exercise of their inherent natural rights, for, happily, the Government of the United States, which gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance, requires only that they who live under its protection should demean themselves as good citizens.”

Joy Hakim, a former teacher, editor, and writer won the prestigious James Michener Prize for her series, A History of US, which has sold over 5 million copies nationwide. From Colonies to Country, one of the volumes in that series, includes the full text of Jefferson’s statute. Hakim is also the author of The Story of Science, published by Smithsonian Books. A graduate of Smith College and Goucher College she has been an Associate Editor at Norfolk’s Virginian-Pilot, and was Assistant Editor at McGraw-Hill’s World News.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

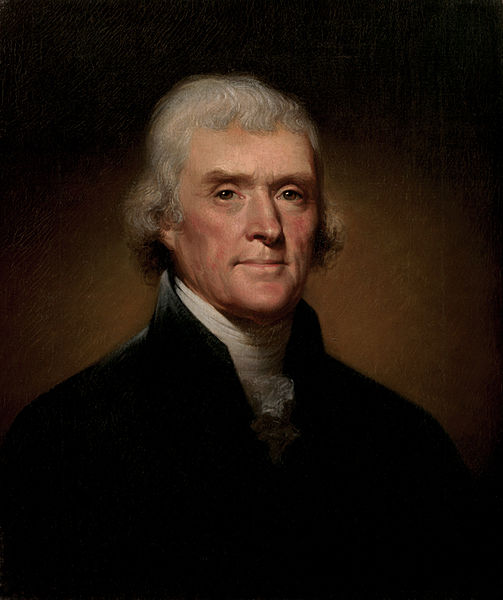

Image Credit: Official Presidential portrait of Thomas Jefferson. 1800. By the White House Historical Association. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Thomas Jefferson’s Statute for Religious Freedom appeared first on OUPblog.

History of US

History of US