Brandon Graham is a maverick. He is most famous for his work on 2009’s King City, but has worked in comics since the 1990s, getting his start in sequential porn before moving into work for Dark Horse, Oni Press, and Image Comics. Known for his clever wit, graffiti-inspired illustration style, and fascination with butts, Graham has carved a niche for himself in the industry that he uses as a platform to explore artistic styles and subjects rarely seen in mainstream American comics. He is currently finishing a run on Rob Liefeld’s Prophet and is about to launch two new Image series. 8House is a fantasy series that features a different creative team in each issue telling short stories that combine to form a cohesive universe. Island is an anthology series that is being curated by Brandon and is designed to reintroduce audiences to the dying art of the comics Zine.

The Beat recently sat down to talk to Brandon about his influences, his work, and what he hopes to accomplish in the years to come.

Alex Lu: King City was one of the first books I read when I was getting into comics. My favorite thing about it was the inordinate number of puns in the story. Do you keep a journal full of them?

Brandon Graham: Oh yeah, it’s obscene how many bad puns made it into that book. I do keep a journal full of jokes and things that make it into the comic, but it’s not necessarily planned. I used to work very hard at making sure I had enough jokes per page, but it wasn’t the most fun way to work so I toned it down.

I used to have a system for making jokes and making puns. More recently, I was trying to find different ways to do humor. I would study Rumiko Takahashi comics, see how she structures her humor, and then try to emulate that. That influence played into the Multiple Warheads series. In doing these non-pun based humor, sometimes the puns would just come in naturally, whereas in King City I’d make lists of possible jokes I could make. I did that a lot, but I didn’t want to keep doing it in everything I did.

Lu: How’s it been working on Prophet, simply being the writer as opposed to playing the role of the artist as well?

Graham: It’s a very different experience. The humor there is much more subtle, as it’s not meant to be a humorous book. That makes it faster to write, and it’s been a really good learning process to collaborate with different people and collaborate on a monthly comic.

Lu: How did you script Prophet?

Graham: A lot of the stuff is just me thumbnailing it– just doing a rough version of the comic, handing them a copy, and letting them do their own versions of the pages. The back of some of the volumes have those rough thumbnails in them. Sometimes I’d even do them in full color.

Lu: Did you find your collaborators sticking to your roughs or deviating from them dramatically?

Graham: It depends on the artist. When I work with my wife, Marian, she doesn’t like me to do layouts. She just likes me to tell her what happens on the page. However, a lot of the guys on Prophet preferred that I did the layouts so they could come in and not have to think about a page too much. They’d just rework it if they had a better idea.

Lu: When Prophet wraps, do you plan on doing more work that’s strictly based in writing, or will you transition back to doing art as well?

Graham: I’m working on doing more illustration. I’m currently doing a magazine, Island, which is an excuse for me to do a lot more short story work and a lot more drawing without a specific sense of place. If I want to do a series of illustrations, now that I have Island I don’t have to worry about finding a home for it. I’m going to be writing five or six issues for the 8House shared fantasy universe each year as well.

Lu: I saw the cover work for 8House. It’s beautiful. How long has that series been in production?

Graham: Quite a while. It’s changed dramatically, but it started as a way to do stuff with some of the Top Cow books. I was going to be doing Pitt, and another team was going to be doing Witchblade. That didn’t work out, but it turned into a new version of itself.

Lu: What’s the basic premise of 8House?

Graham: It basically takes a bunch of creative teams, have them set stories in the same world, and then have them riff off one another. It’ll be interesting to see how teams are influenced by one another, similar to how Marvel and DC have these random books that weren’t originally meant to be part of a shared universe, but have been patched together to form one that people accept.

Prophet was very strict about how the universe worked but 8House is more open. Different stories can be told from different perspectives and they’ll almost feel like they’re in different worlds. It’ll be more like how Fantastic Four and New Gods are in the same universe but feel very different from one another.

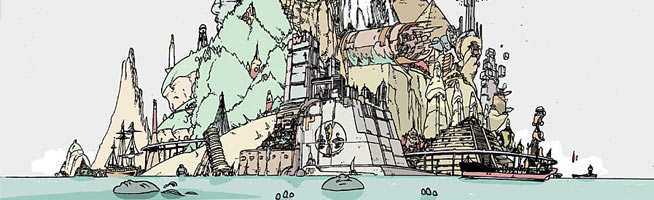

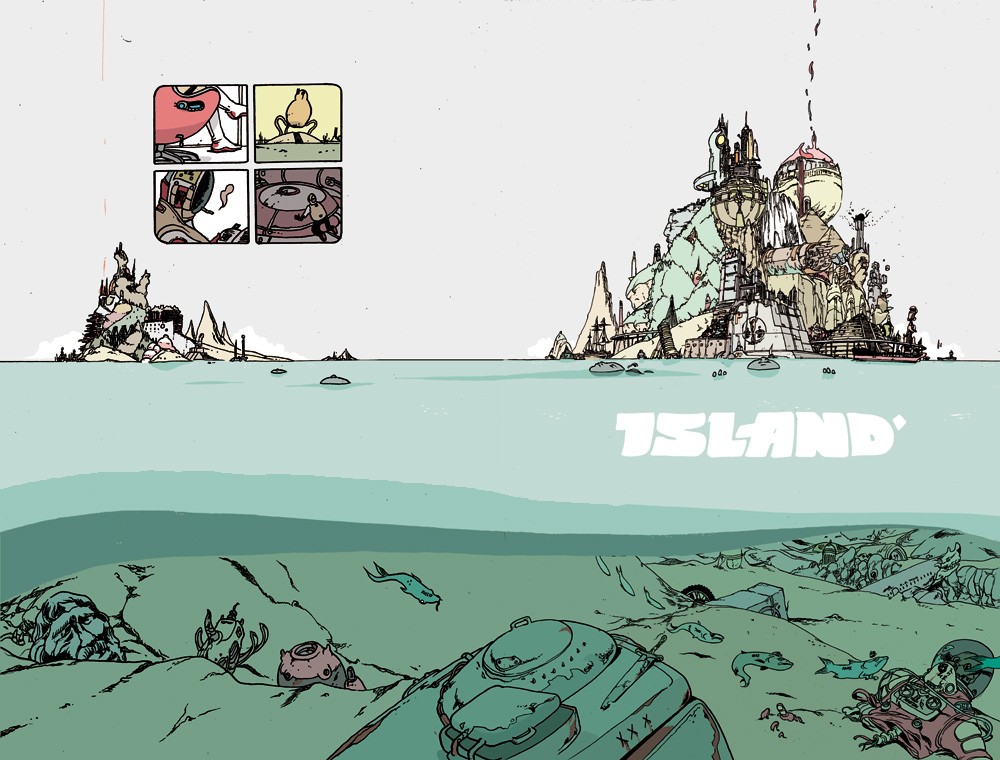

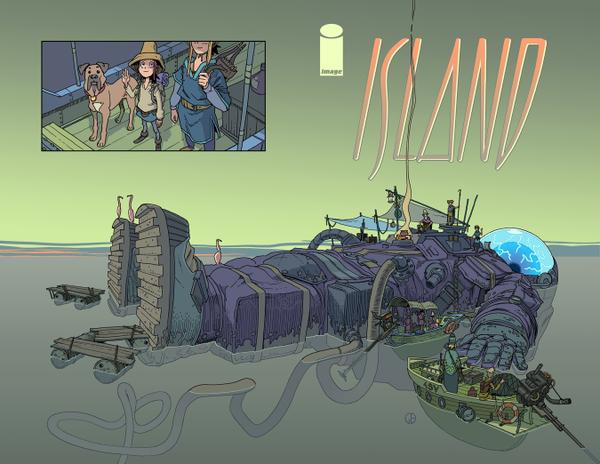

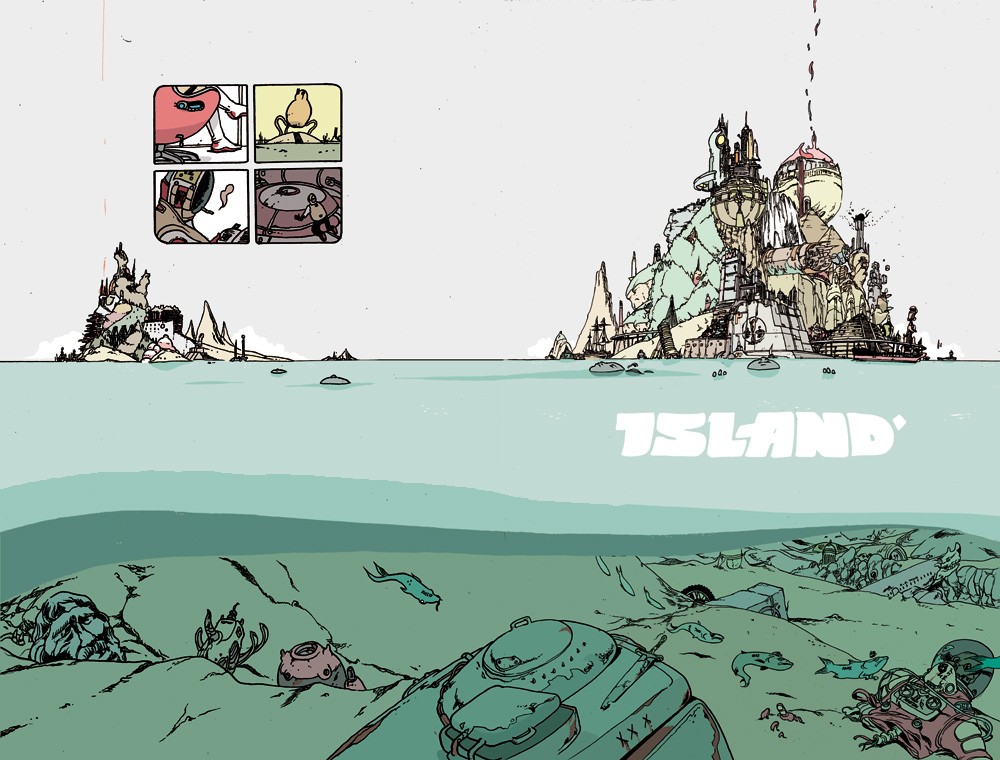

Lu: Awesome. And what’s the premise for Island?

Graham: It’s going to be a monthly title put out by Image, 150 pages per issue. It’ll be distributed through comic stores. It’s about an inch larger in width and height from a standard comic. A lot of the production process involved me thinking about what I wanted to read in an anthology as well as why I didn’t often read anthologies.

A part of it was making sure it felt like a bundle of comics than an anthology. None of the stories are shorter than 20 pages, and some are up to 50 or 60 pages. You pay for this $8.00 book and you get 3 or 4 entire comics, so it’s slightly cheaper than just buying individual issues.

It’s also carefully curated, so if you like one or two artists in the issue you’ll like the other two as well. There’s nothing in there I wouldn’t buy myself, and I’ve been very particular about not playing politics and picking people specifically for their names. I go after quality work.

Lu: So how do you pick the group that ends up in each issue?

Graham: I’m always digging up artists whose work I am excited about, and there’s a huge amount of work that doesn’t get the exposure it deserves. A lot of people stick to specific publishers or genres, and that’s true even in places like Image. I come from a different background from a lot of their creators, so I wanted to bring in creators that I feel more in tune with.

I’m even putting some lesser known older work into Island. There’s a 1986 six issue comic published by Eclipse called Zooniverse that I fell in love with when I was eleven. That’s getting reprinted in Island. There’s also a British small press comic by an artist named Lando called Island 3 that’s only been printed in small press zine format in England that we’ll be printing and bringing to a mass audience.

Lu: It’s pretty unique to have a zine in the modern American comic book industry nowadays, isn’t it?

Graham: Well, you have stuff like Dark Horse Presents… but those stories often feel like they’re intended for different audiences. I’m not trying to do this specifically, but I am trying out untested people. There are new creators in Island, but there are also creators like Emma Ríos (Pretty Deadly) who are coming in and doing their own writing.

Most of the work is single creator– written, drawn, and colored by them. If a writer is in Island, I’ll have them do prose or write an essay. Kelly Sue DeConnick wrote an article in the first issue about a poet who deeply influences her. It’s stuff you wouldn’t see in a normal comic book.

Lu: What’s your hope for Island?

Graham: Well, I hope people are just as excited for it as I am. One of the great things about comics right now is that people that are being given the freedom to do whatever they want at publishers have the opportunity to shape how the industry grows, not only in their work but in the work of people they bring into the industry. If you have a fanbase and people who trust your work, you can tell them to check out the work of someone you admire and help grow the community in that way.

Lu: What specifically has influenced you?

Graham: I used to be strongly influenced by graffiti, but I also did porn comics and it’s all bleeding into my system and becoming something that’s hopefully new. I read a lot, and I’ve been trying to read more novels in order to remind myself that there’s a world outside of comics.

Lu: What are you reading right now?

Graham: I’m reading a Charles Stross book called Saturn’s Children, which is about a sex robot that activates after humanity goes extinct. There’s also Haruki Murakami’s Hardboiled Wonderland and the End of the World, which is my favorite book ever. I remember reading that and thinking that this is just a better version of everything I’m trying to do.

Lu: How do you feel about having a distinctive style that’s strongly influenced the development about several other artists?

Graham: It’s always really exciting to see that. I wear my influences on my sleeve so much that I hope it’s a gateway to people tracking down the work of people I’m influenced by like Moebius or Adam Warren. It’s also a little daunting when you see what you can see what you’ve done in something someone has devoted their life to, but ultimately it’s very exciting.

8House: Arclight #1 releases on June 24th, 2015. Island #1 hits stands on July 15th, 2015.

By Paul Cobb

Recently the jihadist insurgent group formerly known as the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) underwent a re-branding of sorts when one of its leaders, known by the sobriquet Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, was proclaimed caliph by the group’s members. In keeping with the horizonless pretentions that such a title theoretically conveys, the group dropped their geographical focus and embraced a more universalist outlook, settling for the name of the ‘Islamic State’.

As a few observers have noted, the title of caliph comes freighted with a long and complicated history. That history begins in the seventh century AD, when the title was adopted to denote those leaders of the Muslim community who were recognized as the Prophet Muhammad’s “successors”— not prophets themselves of course, but men who were expected, in the Prophet’s absence, to know how to guide the community spiritually as well as politically. Later in the medieval period, classical Islamic political theory sought to carefully define the pool from which caliphs might be drawn and to stipulate specific criteria that a caliph must possess, such as lineage, probity, moral standing and so on. Save for his most ardent followers, Muslims have found al-Baghdadi — with his penchant for Rolex watches and theatrical career reinventions — sorely wanting in such caliphal credentials.

He’s not the only one of course. Over the span of Islamic history, the title of caliph has been adopted by numerous (and sometimes competing) dynasties, rebels, and pretenders. The last ruler to bear the title in any significant way was the Ottoman Abdülmecid II, who lost the title when he was exiled in 1924. And even then it was an honorific supported only by myths of Ottoman legitimacy. But it’s doubtful that al-Baghdadi gives the Ottomans much thought. For he is really tapping into a much more recent dream of reviving the caliphate embraced by various Islamist groups since the early 20th century, who saw it as a precondition for reviving the Muslim community or to combat Western imperialism. Al-Baghdadi’s caliphate is thus a modern confection, despite its medieval trappings.

That an Islamic fundamentalist (to use a contested term of its own) like al-Baghdadi should make an appeal to the past to legitimate himself, and that he should do so without any thoughtful reference to Islamic history, is of course the most banal of observations to make about his activities, or about those of any fundamentalist. And perhaps that is the most interesting point about this episode. For the utterly commonplace nature of examples like al-Baghdadi’s clumsy claim to be caliph suggest that Islamic history today is in danger of becoming irrelevant.

Caliph Abdulmecid II, the last Caliph before Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.

This is not because Islamic history has no bearing upon the present Islamic world, but because present-day agendas that make use of that history prefer to cherry-pick, deform, and obliterate the complicated bits to provide easy narratives for their own ends. Al-Baghdadi’s claim, for example, leaps over 1400 years of more nuanced Islamic history in which the institution of the caliphate shaped Muslim lives in diverse ways, and in which regional upstarts had little legitimate claim. But he is hardly alone in avoiding inconvenient truths — contemporary comment on Middle Eastern affairs routinely employs the same strategy.

We can see just such a history-shy approach in coverage of the sectarian conflicts between Shi’i and Sunni Muslims in Iraq, Syria, Bahrain, Pakistan, and elsewhere. The struggle between Sunnis and Shi’ites, we are usually told, has its origins in a contest over religious authority in the seventh century between the partisans of the Prophet’s cousin and son-in-law ‘Ali and those Muslims who believed the incumbent caliphs of the day were better guides and leaders for the community. And so Shi’ites and Sunnis, we are led to believe, have been fighting ever since. It is as if the past fourteen centuries of history, with its record of coexistence, migrations, imperial designs, and nation-building have no part in the matter, to say nothing of the past century or less of authoritarian regimes, identity-politics, and colonial mischief.

We see the inconvenient truths of Islamic history also being ignored in the widespread discourse of crusading and counter-crusading that occasionally infects comment on contemporary conflicts, as if holy war is the default mode for Muslims fighting non-Muslims or vice-versa. When Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi can wrap himself in black robes and proclaim himself Caliph Ibrahim of the Islamic State, when seventh-century conflicts seem like thorough explanations for twenty-first century struggles, or when a terrorist and mass-murderer like the Norwegian Anders Breivik can see himself as a latter-day Knight Templar, then we are sadly living in a world in which the medieval is allowed to seep uncritically into the contemporary as a way to provide easy answers to very complicated problems.

But we should be wary of such easy answers. Syria and Iraq will not be saved by a caliph. And crusaders would have found the motivations of today’s empire-builders sickening. History properly appreciated should instead lead us to acknowledge the specificity, and indeed oddness, of our modern contexts and the complexity of our contemporary motivations. It should, one hopes, lead to that conclusion reached famously by Mark Twain: that history doesn’t repeat itself, even if sometimes it rhymes.

Paul M. Cobb is Chair and Professor of Islamic History in the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations at the University of Pennsylvania. He is the translator of The Book of Contemplation: Islam and the Crusades and has written a number of other works, most recently The Race for Paradise: An Islamic History of the Crusades.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Caliph Abdulmecid II, by the Library of Congress. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Is Islamic history in danger of becoming irrelevant? appeared first on OUPblog.

By Jon Balserak

For some, it was no surprise to see a book claiming that John Calvin believed he was a prophet. This reaction arose from the fact that they had already thought he was crazy and this just served to further prove the point. One thing to say in favor of their reaction is that at least they are taking the claim seriously; they perceive correctly its gravity: Calvin believed that he spoke for God; that to disagree with him was to disagree with the Almighty ipso facto.

The belief may, of course, appear utterly astonishing and bizarre to us today. While I’m sympathetic with such astonishment, I don’t share it. This is not necessarily because I believe Calvin was a prophet. It’s rather because I know him well enough to know that such a belief is entirely in keeping with his character and I suppose I’ve grown accustomed to it. Most of what comes out of his mouth or flows from his pen carries with it, it seems patently clear to me, a prophetic tone and energy. There’s no question in my mind that he held that the heavens themselves opened when he opened his mouth.

I have friends who ask with some chagrin: “didn’t Calvin feel the same sense of utter uncertainty, confusion, and awkwardness with respect to his own place in the universe that people in the twenty-first century do? Wasn’t he aware of his own weaknesses?” If so, the logic follows, how could he have become convinced that he was a divine messenger since this assumes a certain sense of faultlessness? For one of us to believe ourselves a prophet seems impossible, so, what of Calvin? Didn’t his inner reservations and neuroses weigh on his self-conception and convince him that he couldn’t possibly be the mouthpiece of the Divine? My answer is a simple “no.” I don’t think he believed that he erred in his service of God. Ever.

Let us recall that it’s Calvin who indicted the greatest theologians with the charge that they had mixed hay with gold, stubble with silver, and wood with precious stones (a reference to the Apostle Paul’s warning to those who had corrupted their labors in God’s service in 1 Corinthians 3: 15). He indicted Cyprian, Ambrose, Augustine, and some from what he referred to as more recent times, such as Gregory and Bernard. He said of these individuals that they could only be saved on the condition that God wipe away their ignorance and the stain which corrupted their work. They could only be saved as through fire. He even said this of Augustine, the Theologian par excellence for everyone in Early Modern Europe. Let us recall as well that Calvin could write in 1562, just two years before he died, that if anyone were his enemy, then they were the enemies of Christ. He goes on in this writing, entitled Responsio ad Balduini Convicia, to say that he had never taken up a position out of a hostile personal motive or being prompted by spite. He insists, in fact, in language that is astounding to read that anyone who is his enemy feels this way about him because they oppose the good of the church and they hate godly teaching. This is Calvin. This is the prophet; the one to whom the mantle of Elijah had been passed.

The natural question to ask at this point is whether Calvin believed that his writings should be added to the canon of Scripture? It might seem only logical, according to what I’m arguing, that he did. However it would, of course, be extremely difficult to justify such a claim. But I don’t think that’s all that can be said on the question. For there is a logic to the idea that not only Calvin but also Zwingli, Luther, Knox, and others who believed themselves raised up as prophets might have thought this. There are, moreover, numerous vocational, temperamental, theological, strategic, psychological, doctrinal, and relational reasons that would need to be taken into account before drawing a conclusion one way or the other on the question. I don’t put it out of the realm of possibility that Calvin could have believed this, at least at some level. He did, after all, tell his fellow ministers on his death bed that they were to “change nothing,” suggesting that the foundation he had laid was perfect and, thus, that the repository representing that foundation—namely, his biblical commentaries, lectures, theological treatises, and magnum opus, The Institutes of the Christian Religion—should serve as the origin from which the Christian church was to be rebuilt. So I would not be utterly shocked if he did, in fact, believe that his oeuvre should be made part of the canon of Scripture. Unfortunately, we will never know.

Jon Balserak is currently Associate Professor of Religious Studies at the University of Bristol. He is an historian of Renaissance and Early Modern Europe, particularly France and the Swiss Confederation. He also works on textual scholarship, electronic editing and digital editions. His latest book is John Calvin as Sixteenth Century Prophet (OUP, 2014).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only religion articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post John Calvin’s authority as a prophecy appeared first on OUPblog.

I’ve been loving the recent interview series here at the Beat.

So does that mean the the Prophet Earth War LS is finally seeing the light of day? The Image site stopped listing it so I figured Prophet was done after the Strikefiles.

Yeah. When is Prophet coming back out?