Adapting animated films for the stage is no longer just the domain of feature films like "The Lion King" and "Shrek." Italian dance/theater troupe "eVolution" has adapted an unlikely animated short for live performance: Don Hertzfeldt's "Billy's Balloon."

Add a CommentViewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: evolution, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 26 - 50 of 81

Blog: Cartoon Brew (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Don Hertzfeldt, Billy's Balloon, Dance, Theater, Evolution, Electricity, Add a tag

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: neanderthal, molecular biology, homo sapiens, neanderthals, asians, *Featured, oxford journals, Classics & Archaeology, Science & Medicine, Health & Medicine, Earth & Life Sciences, hominins, HYAL region, molecular biology and evolution, peking man, qiling ding, UV-A, UV-B, ya hu, introgression, hyal, eurasians, hyal2, Journals, evolution, Add a tag

By Qiliang Ding and Ya Hu

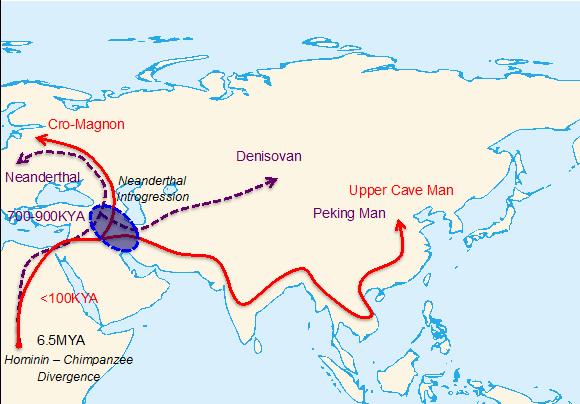

Hominins and their closest living relative, chimpanzees, diverged approximately 6.5 million years ago on African continent. Fossil evidence suggests hominins have migrated away from Africa at least twice since then. Crania of the first wave of migrants, such as Neanderthals in Europe and Peking Man in East Asia, show distinct morphological features that are different from contemporary humans (also known as Homo sapiens sapiens). The first wave of migration was estimated to have occurred 7-9,000,000 years ago. In the 1990s, studies on Y-chromosome and mitochondrial DNA proved that the contemporary Eurasians are descendants of the second wave of migrants, who migrated out of Africa less than 100,000 years ago.

It has been reported that the habitats of Neanderthals and ancestors of contemporary Eurasians overlapped both in time and space, and therefore provides possibility of introgression between Neanderthals and ancestors of Eurasians. This possibility is confirmed by recent studies, which suggest that about 1-4% of Eurasian genomes are from Neanderthal introgression.

Adaptation to local environment is crucial for newly-arrived migrants, and the process of local adaptation is sometimes time-consuming. Since Neanderthals arrived in Eurasia ten times earlier than ancestors of Eurasians, we are trying to figure out whether the Neanderthal introgressions helped the ancestors of Eurasians adapt to the local environment.

Two major out-of-Africa migration waves of hominins. The purple and red colors represent the first and second migration waves, respectively. The circle near Middle East represents a possible location where main Neanderthal introgression might have occurred.

Our study reports that Neanderthal introgressive segments on chromosome 3 may have helped East Asians adapting to the intensity of ultraviolet-B (UV-B) irradiation in sunlight. We call the region containing the Neanderthal introgression the “HYAL” region, as it contains three genes that encode hyaluronoglucosaminidases.

We first noticed that the entire HYAL region is included in an unusually large linkage disequilibrium (LD) block in East Asian populations. Such a large LD block is a typical signature of positive natural selection. More interestingly, it is observed that some Eurasian haplotypes at the HYAL region show a closer relationship to the Neanderthal haplotype than to the contemporary African haplotypes, implicating recent Neanderthal introgression. We confirmed the Neanderthal introgression in HYAL region by employing a series of statistical and population genetic analyses.

Further, we examined whether the HYAL region was under positive natural selection using two published statistical tests. Both suggest that the HYAL region was under positive natural selection, and pinpoint a set of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) contributed by Neanderthal introgression as the candidate targets of positive natural selection.

We then explored the potential functional importance of Neanderthal introgression in the HYAL region. The HYAL genes attracted our attention, as they are important in hyaluronan metabolism and cellular response to UV-B irradiation. We noticed that an SNP pinpointed as a potential target for positive natural selection was located in the most conservative exon of HYAL2 gene. We suspect that this SNP (known as rs35455589) may have altered the function of HYAL2 protein, since this SNP is also associated with the risk of keloid, a dermatological disorder related to hyaluronan metabolism.

Next, we interrogated the global distribution of Neanderthal introgression at the HYAL region. It is observed that the Neanderthal introgression reaches a very high frequency in East Asian populations, which ranges from 49.4% in Japanese to 66.5% in Southern Han Chinese. The frequency of Neanderthal introgression is higher in southern East Asian populations compared to northern East Asian populations. Such evidence might suggest latitude-dependent selection, which implicates the role of UV-B intensity.

We discovered that Neanderthal introgression on chromosome 3 was under positive natural selection in East Asians. We also found that a gene (HYAL2) in the introgressive region is related to the cellular response to UV-B, and an allele from Neanderthal introgression may have altered the function of HYAL2. As such, we think it is possible that Neanderthals may have helped East Asians to adapt to sunlight.

Qiliang Ding and Ya Hu are MSc Students at the Institute of Genetics at Fudan University and Intern Students at the CAS-MPG Partner Institute of Computational Biology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. Their research interest lies in revealing evolutionary history of hominids using ancient and contemporary human genomes. They are the authors of the paper “Neanderthal Introgression at Chromosome 3p21.31 Was Under Positive Natural Selection in East Asians,” which appears in the journal Molecular Biology and Evolution.

Molecular Biology and Evolution publishes research at the interface of molecular (including genomics) and evolutionary biology.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only earth, environmental, and life sciences articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Background map via Wikimedia Commons, with annotations by the authors.

The post Neanderthals may have helped East Asians adapting to sunlight appeared first on OUPblog.

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: science, Philosophy, evolution, Anthropology, climate change, morality, humanity, Medical Ethics, Humanities, panacea, Social Sciences, Editor's Picks, *Featured, human condition, ingmar persson, julian savulescu, jury theorem, liberal democracy, moral bioenhancement, moral psychology, philosophy now, tragedy of the commons, unfit for the future, urgent need for moral enhancement, ethics, politics, Add a tag

By Julian Savulescu and Ingmar Persson

First published in Philosophy Now Issue 91, July/Aug 2012.

For the vast majority of our 150,000 years or so on the planet, we lived in small, close-knit groups, working hard with primitive tools to scratch sufficient food and shelter from the land. Sometimes we competed with other small groups for limited resources. Thanks to evolution, we are supremely well adapted to that world, not only physically, but psychologically, socially and through our moral dispositions.

But this is no longer the world in which we live. The rapid advances of science and technology have radically altered our circumstances over just a few centuries. The population has increased a thousand times since the agricultural revolution eight thousand years ago. Human societies consist of millions of people. Where our ancestors’ tools shaped the few acres on which they lived, the technologies we use today have effects across the world, and across time, with the hangovers of climate change and nuclear disaster stretching far into the future. The pace of scientific change is exponential. But has our moral psychology kept up?

With great power comes great responsibility. However, evolutionary pressures have not developed for us a psychology that enables us to cope with the moral problems our new power creates. Our political and economic systems only exacerbate this. Industrialisation and mechanisation have enabled us to exploit natural resources so efficiently that we have over-stressed two-thirds of the most important eco-systems.

A basic fact about the human condition is that it is easier for us to harm each other than to benefit each other. It is easier for us to kill than it is for us to save a life; easier to injure than to cure. Scientific developments have enhanced our capacity to benefit, but they have enhanced our ability to harm still further. As a result, our power to harm is overwhelming. We are capable of forever putting an end to all higher life on this planet. Our success in learning to manipulate the world around us has left us facing two major threats: climate change – along with the attendant problems caused by increasingly scarce natural resources – and war, using immensely powerful weapons. What is to be done to counter these threats?

Our Natural Moral Psychology

Our sense of morality developed around the imbalance between our capacities to harm and to benefit on the small scale, in groups the size of a small village or a nomadic tribe – no bigger than a hundred and fifty or so people. To take the most basic example, we naturally feel bad when we cause harm to others within our social groups. And commonsense morality links responsibility directly to causation: the more we feel we caused an outcome, the more we feel responsible for it. So causing a harm feels worse than neglecting to create a benefit. The set of rights that we have developed from this basic rule includes rights not to be harmed, but not rights to receive benefits. And we typically extend these rights only to our small group of family and close acquaintances. When we lived in small groups, these rights were sufficient to prevent us harming one another. But in the age of the global society and of weapons with global reach, they cannot protect us well enough.

There are three other aspects of our evolved psychology which have similarly emerged from the imbalance between the ease of harming and the difficulty of benefiting, and which likewise have been protective in the past, but leave us open now to unprecedented risk:

- Our vulnerability to harm has left us loss-averse, preferring to protect against losses than to seek benefits of a similar level.

- We naturally focus on the immediate future, and on our immediate circle of friends. We discount the distant future in making judgements, and can only empathise with a few individuals based on their proximity or similarity to us, rather than, say, on the basis of their situations. So our ability to cooperate, applying our notions of fairness and justice, is limited to our circle, a small circle of family and friends. Strangers, or out-group members, in contrast, are generally mistrusted, their tragedies downplayed, and their offences magnified.

- We feel responsible if we have individually caused a bad outcome, but less responsible if we are part of a large group causing the same outcome and our own actions can’t be singled out.

Case Study: Climate Change and the Tragedy of the Commons

There is a well-known cooperation or coordination problem called ‘the tragedy of the commons’. In its original terms, it asks whether a group of village herdsmen sharing common pasture can trust each other to the extent that it will be rational for each of them to reduce the grazing of their own cattle when necessary to prevent over-grazing. One herdsman alone cannot achieve the necessary saving if the others continue to over-exploit the resource. If they simply use up the resource he has saved, he has lost his own chance to graze but has gained no long term security, so it is not rational for him to self-sacrifice. It is rational for an individual to reduce his own herd’s grazing only if he can trust a sufficient number of other herdsmen to do the same. Consequently, if the herdsmen do not trust each other, most of them will fail to reduce their grazing, with the result that they will all starve.

The tragedy of the commons can serve as a simplified small-scale model of our current environmental problems, which are caused by billions of polluters, each of whom contributes some individually-undetectable amount of carbon dioxide to the atmosphere. Unfortunately, in such a model, the larger the number of participants the more inevitable the tragedy, since the larger the group, the less concern and trust the participants have for one another. Also, it is harder to detect free-riders in a larger group, and humans are prone to free ride, benefiting from the sacrifice of others while refusing to sacrifice themselves. Moreover, individual damage is likely to become imperceptible, preventing effective shaming mechanisms and reducing individual guilt.

Anthropogenic climate change and environmental destruction have additional complicating factors. Although there is a large body of scientific work showing that the human emission of greenhouse gases contributes to global climate change, it is still possible to entertain doubts about the exact scale of the effects we are causing – for example, whether our actions will make the global temperature increase by 2°C or whether it will go higher, even to 4°C – and how harmful such a climate change will be.

In addition, our bias towards the near future leaves us less able to adequately appreciate the graver effects of our actions, as they will occur in the more remote future. The damage we’re responsible for today will probably not begin to bite until the end of the present century. We will not benefit from even drastic action now, and nor will our children. Similarly, although the affluent countries are responsible for the greatest emissions, it is in general destitute countries in the South that will suffer most from their harmful effects (although Australia and the south-west of the United States will also have their fair share of droughts). Our limited and parochial altruism is not strong enough to provide a reason for us to give up our consumerist life-styles for the sake of our distant descendants, or our distant contemporaries in far-away places.

Given the psychological obstacles preventing us from voluntarily dealing with climate change, effective changes would need to be enforced by legislation. However, politicians in democracies are unlikely to propose such legislation. Effective measures will need to be tough, and so are unlikely to win a political leader a second term in office. Can voters be persuaded to sacrifice their own comfort and convenience to protect the interests of people who are not even born yet, or to protect species of animals they have never even heard of? Will democracy ever be able to free itself from powerful industrial interests? Democracy is likely to fail. Developed countries have the technology and wealth to deal with climate change, but we do not have the political will.

If we keep believing that responsibility is directly linked to causation, that we are more responsible for the results of our actions than the results of our omissions, and that if we share responsibility for an outcome with others our individual responsibility is lowered or removed, then we will not be able to solve modern problems like climate change, where each person’s actions contribute imperceptibly but inevitably. If we reject these beliefs, we will see that we in the rich, developed countries are more responsible for the misery occurring in destitute, developing countries than we are spontaneously inclined to think. But will our attitudes change?

Moral Bioenhancement

Our moral shortcomings are preventing our political institutions from acting effectively. Enhancing our moral motivation would enable us to act better for distant people, future generations, and non-human animals. One method to achieve this enhancement is already practised in all societies: moral education. Al Gore, Friends of the Earth and Oxfam have already had success with campaigns vividly representing the problems our selfish actions are creating for others – others around the world and in the future. But there is another possibility emerging. Our knowledge of human biology – in particular of genetics and neurobiology – is beginning to enable us to directly affect the biological or physiological bases of human motivation, either through drugs, or through genetic selection or engineering, or by using external devices that affect the brain or the learning process. We could use these techniques to overcome the moral and psychological shortcomings that imperil the human species. We are at the early stages of such research, but there are few cogent philosophical or moral objections to the use of specifically biomedical moral enhancement – or moral bioenhancement. In fact, the risks we face are so serious that it is imperative we explore every possibility of developing moral bioenhancement technologies – not to replace traditional moral education, but to complement it. We simply can’t afford to miss opportunities. We have provided ourselves with the tools to end worthwhile life on Earth forever. Nuclear war, with the weapons already in existence today could achieve this alone. If we must possess such a formidable power, it should be entrusted only to those who are both morally enlightened and adequately informed.

Objection 1: Too Little, Too Late?

We already have the weapons, and we are already on the path to disastrous climate change, so perhaps there is not enough time for this enhancement to take place. Moral educators have existed within societies across the world for thousands of years – Buddha, Confucius and Socrates, to name only three – yet we still lack the basic ethical skills we need to ensure our own survival is not jeopardised. As for moral bioenhancement, it remains a field in its infancy.

We do not dispute this. The relevant research is in its inception, and there is no guarantee that it will deliver in time, or at all. Our claim is merely that the requisite moral enhancement is theoretically possible – in other words, that we are not biologically or genetically doomed to cause our own destruction – and that we should do what we can to achieve it.

Objection 2: The Bootstrapping Problem

We face an uncomfortable dilemma as we seek out and implement such enhancements: they will have to be developed and selected by the very people who are in need of them, and as with all science, moral bioenhancement technologies will be open to abuse, misuse or even a simple lack of funding or resources.

The risks of misapplying any powerful technology are serious. Good moral reasoning was often overruled in small communities with simple technology, but now failure of morality to guide us could have cataclysmic consequences. A turning point was reached at the middle of the last century with the invention of the atomic bomb. For the first time, continued technological progress was no longer clearly to the overall advantage of humanity. That is not to say we should therefore halt all scientific endeavour. It is possible for humankind to improve morally to the extent that we can use our new and overwhelming powers of action for the better. The very progress of science and technology increases this possibility by promising to supply new instruments of moral enhancement, which could be applied alongside traditional moral education.

Objection 3: Liberal Democracy – a Panacea?

In recent years we have put a lot of faith in the power of democracy. Some have even argued that democracy will bring an ‘end’ to history, in the sense that it will end social and political development by reaching its summit. Surely democratic decision-making, drawing on the best available scientific evidence, will enable government action to avoid the looming threats to our future, without any need for moral enhancement?

In fact, as things stand today, it seems more likely that democracy will bring history to an end in a different sense: through a failure to mitigate human-induced climate change and environmental degradation. This prospect is bad enough, but increasing scarcity of natural resources brings an increased risk of wars, which, with our weapons of mass destruction, makes complete destruction only too plausible.

Sometimes an appeal is made to the so-called ‘jury theorem’ to support the prospect of democracy reaching the right decisions: even if voters are on average only slightly more likely to get a choice right than wrong – suppose they are right 51% of the time – then, where there is a sufficiently large numbers of voters, a majority of the voters (ie, 51%) is almost certain to make the right choice.

However, if the evolutionary biases we have already mentioned – our parochial altruism and bias towards the near future – influence our attitudes to climatic and environmental policies, then there is good reason to believe that voters are more likely to get it wrong than right. The jury theorem then means it’s almost certain that a majority will opt for the wrong policies! Nor should we take it for granted that the right climatic and environmental policy will always appear in manifestoes. Powerful business interests and mass media control might block effective environmental policy in a market economy.

Conclusion

Modern technology provides us with many means to cause our downfall, and our natural moral psychology does not provide us with the means to prevent it. The moral enhancement of humankind is necessary for there to be a way out of this predicament. If we are to avoid catastrophe by misguided employment of our power, we need to be morally motivated to a higher degree (as well as adequately informed about relevant facts). A stronger focus on moral education could go some way to achieving this, but as already remarked, this method has had only modest success during the last couple of millennia. Our growing knowledge of biology, especially genetics and neurobiology, could deliver additional moral enhancement, such as drugs or genetic modifications, or devices to augment moral education.

The development and application of such techniques is risky – it is after all humans in their current morally-inept state who must apply them – but we think that our present situation is so desperate that this course of action must be investigated.

We have radically transformed our social and natural environments by technology, while our moral dispositions have remained virtually unchanged. We must now consider applying technology to our own nature, supporting our efforts to cope with the external environment that we have created.

Biomedical means of moral enhancement may turn out to be no more effective than traditional means of moral education or social reform, but they should not be rejected out of hand. Advances are already being made in this area. However, it is too early to predict how, or even if, any moral bioenhancement scheme will be achieved. Our ambition is not to launch a definitive and detailed solution to climate change or other mega-problems. Perhaps there is no realistic solution. Our ambition at this point is simply to put moral enhancement in general, and moral bioenhancement in particular, on the table. Last century we spent vast amounts of resources increasing our ability to cause great harm. It would be sad if, in this century, we reject opportunities to increase our capacity to create benefits, or at least to prevent such harm.

© Prof. Julian Savulescu and Prof. Ingmar Persson 2012

Julian Savulescu is a Professor of Philosophy at Oxford University and Ingmar Persson is a Professor of Philosophy at the University of Gothenburg. This article is drawn from their book Unfit for the Future: The Urgent Need for Moral Enhancement (Oxford University Press, 2012).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only philosophy articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the ![]()

![]()

Blog: I.N.K.: Interesting Non fiction for Kids (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Deborah Heiligman, 2009 titles, finding the truth, climate science, The New York Times, evolution, Add a tag

I had all kinds of ideas about what I was going to write about for today. Science and art. A term called The Beholder's Share. I was going to tell you about a great trip I had in Maine, where I spoke to librarians about writing non-fiction. I was going to show you a cool NPR story about the wind at sea looking like a Van Gogh sky. But then I opened up the New York Times Monday morning and saw this:

Pseudoscience and Tennessee’s Classrooms

Please read it. I'll wait. I can't say it any better than that because all I want to do is scream. Loudly.

But I will say this, once again, as I've said many times and I think as I showed in CHARLES AND EMMA: Science and faith can co-exist. It does not have to be either or. But science is science and religion is religion. Evolution really happens. Smart theologians, religious people, clerics, rabbis, priests, ministers have NO PROBLEM WITH EVOLUTION. (I guess I am screaming.)

Our children deserve to be taught the truth in school. Period, the end.

Global warming really is happening. Smart politicians know that. Teaching our children the truth about global warming leaves open the possibility of saving our earth. Not teaching them the truth closes that possibility.

I hate conflict and controversy. I got very little of it, thank goodness, when Charles And Emma came out. I think because their relationship shows how science and religion can co-exist in peace and harmony with understanding. That's beautiful.

What's happening in Tennessee and elsewhere is not beautiful. It's UGLY. And stupid. I'm going to let Spencer Tracy say it for me: Inherit The Wind

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Religion, evolution, creationism, atheism, Humanities, Jason Rosenhouse, *Featured, rosenhouse, Taking Sudoku Seriously, creationists, Among the Creationists, Dispatches From the Anti-Evolutionist Front Line, The Monty Hall Problem, Add a tag

By Jason Rosenhouse

In May 2000 I began a post-doctoral position in the Mathematics Department at Kansas State University. Shortly after I arrived I learned of a conference for homeschoolers to be held in Wichita, the state’s largest city. Since that was a short drive from my home, and since anything related to public education in Kansas had relevance to my new job, I decided, on a whim, to attend.

You might recall that Kansas was then embroiled in a battle over state science standards. A politically conservative school board had made a number of changes to existing standards, including the virtual elimination of evolution and the Big Bang. This was very much on the mind of my fellow conference attendees, most of whom were homeschooling for specifically religious reasons. The conference keynoters all hailed form Answers in Genesis, an advocacy group that endorses creationism.

As a politically liberal mathematician who accepted the scientific consensus on evolution, this was all new to me. Curious to learn more, I struck up conversations with other audience members and participated in Q&A sessions whenever I could. The Wichita conference became the first of many that I attended over the next decade. This immersion in the creationist subculture taught me a few things about America’s hostility to evolution.

Some of what I learned was predictable. Though my conversation partners typically spoke with great confidence on a variety of scientific topics, it was rare that they really understood much about the theory they so despised. For me this problem was especially acute when they discussed mathematics. I lost track of how many times folks would tell me that probability theory refuted evolution, and then defend their view with absurd calculations bearing no resemblance to reality. If you are possessed of even a rudimentary understanding of basic science, then you quickly realize the extent to which they have neglected their homework.

Also unsurprising was the insularity I found. For many of the people I met, evangelical Christianity represented a tiny island of righteousness adrift in a sea of secular evil. At virtually every conference one or more speakers would warn of the seductions of “the world’s” wisdom, which is to say the world outside of their own tiny enclave. As they saw it, evolution was just one tool among many in the arsenal of God’s enemies.

But I also learned some things that surprised me. On many occasions I asked people the blunt question, “What do you find so objectionable about evolution?” Never once did anyone reply, “It is contrary to the Bible.” Conflicts with Scripture were certainly an issue, and these concerns arose almost inevitably if the conversation persisted long enough. They were never the paramount concern, however. It is not as though they thought evolution was an intriguing idea, but felt honor bound to reject it because the Bible forced them to. Instead, they flatly despised evolution, usually for reasons having nothing to do with the Bible.

They were horrified, for example, by the savagery and waste entailed by the evolutionary process. You can imagine how it looks to them to suggest that a God of love and justice, who declares his creation to be “very good,” would employ a method of creation which rewards any behavior, no matter how cruel or sadistic, so long as it inserts your genes into the next generation.

And what are we to make of humanity’s significance in Darwin’s world? Tradition teaches we are the pinnacle of creation, unique among the animals for being created in God’s image. Science tells a different story, one in which we are just an inciden

Blog: I.N.K.: Interesting Non fiction for Kids (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: science, evolution, Deborah Heiligman, Alan Alda, Add a tag

|

| Alan Alda, My Friend |

Of course he doesn't know that, but don't we all feel that way about him? I grew up watching M*A*S*H. I just know he's a great guy. I saw him eating lunch a couple of years ago in one of my neighborhood restaurants, like a regular person, so that alone proves it. I went to a staged reading of a play he wrote about Marie Curie. The play, Radiance, had a lot going for it, most of all his passion for the subject, which he talks about here, in an essay for the Huffington Post called "In Love with Marie." The essay is worth reading not only for the subject matter but also because it is how so many of us non-fiction writers feel about the people (and subjects) we are writing about.

I am not alone in Alda love. I know this. My friend Rebecca used to drag her mother to the inferior Chinese restaurant in their neighborhood because Alan Alda ate there. His photo was in the window. Of course she did. What are so-so cold sesame noodles compared to Alan Hawkeye Alda? And I adore great cold sesame noodles.

I would like to say to Alan, as William Thacker's sister, Honey, says to movie star Anna Scott in Notting Hill, "I genuinely believe and have believed for some time now that we can be best friends. What do YOU think?"

(I also believe that I could be best friends with Julia Roberts, but maybe that's because I've watched Notting Hill 1,424 times.)

Also, as long as I'm off on a tangent, my favorite M*A*S*H episode was the heartbreaking one with Blythe Danner called "The More I See You." (I looked it up. Tried to embed video. Couldn't find any. Had to order it from Netflix. This blog post is taking many, many, many pomodoros.)

Where was I? Yes, Alan Alda. Here's the latest reason to be smitten with him. He is the cofounder of The Center for Communicating Science at Stonybrook. And he has recently issued THE FLAME CHALLENGE.

Here's Alan explaining it in SCIENCE Magazine:

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Education, evolution, Charles Darwin, biodiversity, antibiotics, Social Sciences, *Featured, Environmental & Life Sciences, sinatra, Science & Medicine, E. Margaret Evans, Evolution Challenges, Gale M. Sinatra, Karl S. Rosengren, Sarah K. Brem, brem, rosengren, Add a tag

Italian panel depicting Charles Darwin, created ca. 1890, on display at the Turin Museum of Human Anatomy. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

By Karl S. Rosengren, Sarah K. Brem, E. Margaret Evans and Gale M. Sinatra

Today is Darwin’s birthday. It’s doubtful that any scientist would deny Darwin’s importance, that his work provides the field of biology with its core structure, by providing a beautiful, powerful mechanism to explain the diversity of form and function that we see all around us in the living world. But being of importance to one’s field is only one way we judge a scientist’s contributions. There is also the matter of how their work has changed lives all over the world, even of those who don’t know or necessarily care about their accomplishments. What has Darwin done for his fellow human beings? Why should they care about what he showed us, or want to learn what he had to teach?

Understanding evolution is challenging, for many reasons. We often point to the religious questions raised by his work as the cause of these difficulties, but there are many more. No creature decides to change their DNA, nor can a species foresee what they should become to survive, but it sure seems like they do. Evolution provides such elegant solutions to incredibly complex problems, it’s hard to see them as the product of random variation and selection. Even for people who lack religious convictions that make evolution discomforting, it’s hard to grasp the mechanisms of evolution. This difficulty arises out of developmental constraints that lead us to look for centralized, intentional agents when we make causal attributions. It comes out of the challenges inherent in altering our conceptions of the world and replacing one belief system with another, and out of the emotional reaction we have to facing the reality that we are not special or superior to our biological cousins, nor are we in control of the fate of our species in generations to come.

If we’re going to ask people to expend the time and effort it requires to wrap their heads around a idea like biological evolution, it seems as though there ought to be a really big payoff for all that work. So, what does learning about evolution get us?

We’ve asked this question to quite a few teachers, biologists, philosophers, and educational researchers along the course of several projects, the most extensive and recent being the one that led to the edited volume OUP will be putting out soon on teaching and learning about evolution. The reaction is almost always the same. First, there is the pause, as they blink, startled that anyone would be asking such a thing. Often they call upon evolution’s importance to science, and its beauty and elegance — who wouldn’t want to spend their time contemplating that? But if pushed back, and asked what practical value they could point to that would make the struggle of mastering these complex ideas worthwhile, they have a hard time coming up with an answer. The most common responses revolve around the (mis)use of antibiotics, and that people need to know that taking these drugs too often could cause real long-term harm. The second most popular argument is that people should understand the importance of biodiversity, how fragile species become when their gene pool dwindles and ecological balances are disrupted, and that being a part of nature — not above it — comes with responsibili

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Humanities, missing link, fossil, Social Sciences, *Featured, Classics & Archaeology, sediba, human origins, palaeoanthropology, pre-humanoid, interrelatedness, links, History, science, Video, youtube, evolution, Darwin, Anthropology, missing, Add a tag

The search for human origins is a fascinating story – from the Middle Ages, when questions of the earth’s antiquity first began to arise, through to the latest genetic discoveries that show the interrelatedness of all living creatures. Central to the story is the part played by fossils – first, in establishing the age of the Earth; then, following Darwin, in the pursuit of possible ‘Missing Links’ that would establish whether or not humans and chimpanzees share a common ancestor. John Reader’s passion for this quest – palaeoanthropology – began in the 1960s when he reported for Life Magazine on Richard Leakey’s first fossil-hunting expedition to the badlands of East Turkana, in Kenya. Drawing on both historic and recent research, he tells the fascinating story of the science as it has developed from the activities of a few dedicated individuals, into the rigorous multidisciplinary work of today.

In these videos, John Reader, author of Missing Links: In Search of Human Origins talks about the treasure hunt that is the search for the missing link.

Is it possible to discover the missing link?

Click here to view the embedded video.

What is it like finding the remains of an ancient pre-humanoid?

Click here to view the embedded video.

Can scientists draw firm conclusions from fossil finds?

Click here to view the embedded video.

John Reader is Honorary Research Fellow in the Department of Anthropology, University College London. A writer and photographer with more than fifty years of professional experience, his work has included contributions to major international publications, television documentaries and a number of books, including including The Untold History of the Potato, Africa, Pyramids of Life with Harvey Croze, and Rise of Life. His latest book, Missing Links: In Search of Human Origins, published in October 2011. John Reader has previously written about Australopithecus sediba for OUPblog.

View more about this book on the ![]()

![]()

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Psychology, evolution, Anthropology, homo sapiens, Humanities, cognitive psychology, *Featured, Science & Medicine, frederick l coolidge, homo heidelbergensis, neanderthal, linguistics, homo, wynn, language history, how to think like a neandertal, neandertal speech, paleoanthropology, thomas wynn, neandertal, neandertal, neandertals, neandertals, heidelbergensis, sapiens, Add a tag

By Thomas Wynn and Frederick L. Coolidge

Neandertal communication must have been different from modern language. To repeat a point made often in this book, Neandertals were not a stage of evolution that preceded modern humans. They were a distinct population that had a separate evolutionary history for several hundred thousand years, during which time they evolved a number of derived characteristics not shared with Homo sapiens sapiens. At the same time, a continent away, our ancestors were evolving as well. Undoubtedly both Neandertals and Homo sapiens sapiens continued to share many characteristics that each retained from their common ancestor, including characteristics of communication. To put it another way, the only features that we can confidently assign to both Neandertals and Homo sapiens sapiens are features inherited from Homo heidelbergensis. If Homo heidelbergensis communicated via modern style words and modern syntax, then we can safely attribute these to Neandertals as well. Most scholars find this highly unlikely, largely because Homo heidelbergensis brains were slightly smaller than ours and smaller than Neandertals’, but also because the archaeological record of Homo heidelbergensis is much less ‘modern’ than either ours or Neandertals’. Thus, we must conclude that Neandertal communication had evolved along its own path, and that this path may have been quite different from the one followed by our ancestors. The result must have been a difference far greater than the difference between Chinese and English, or indeed between any pair of human languages. Specifying just how Neandertal communication differed from ours may be impossible, at least at our current level of understanding. But we can attempt to set out general features of Neandertal communication based on what we know from the comparative, fossil, and archaeological records.

As we have tried to show in previous chapters, the paleoanthropological record of Neandertals suggests that they relied heavily on two styles of thinking – expert cognition and embodied social cognition. These, at least, are the cognitive styles that best encompass what we know of Neandertal daily life. And they do carry implications for communication. Neandertals were expert stone knappers, relied on detailed knowledge of landscape, and a large body of hunting tactics. It is possible that all of this knowledge existed as alinguistic motor procedures learned through observation, failure, and repetition. We just think it unlikely. If an experienced knapper could focus the attention of a novice using words it would be easier to learn Levallois. Even more useful would be labels for features of the landscape, and perhaps even routes, enabling Neandertal hunters to refer to any location in their territories. Such labels would almost have been required if widely dispersed foraging groups needed to congregate at certain places (e.g., La Cotte). And most critical of all, in a natural selection sense, would be an ability to indicate a hunting tactic prior to execution. These labels must have been words of some kind. We suspect that Neandertal words were always embedded in a rich social and environmental context that included gesturing (e.g., pointing) and emotionally laden tones of voice, much as most human vocal communication is similarly embedded, a feature of communication probably inherited from Homo heidelbergensis.

At the risk of crawling even further out on a limb than the two of us usually go, we make the following suggestions about Neandertal communication:

1) Neandertals had speech. Their expanded Broca’s area in the brain, and their possession of a human FOXP2 gene both suggest this. Neandertal speech was probably based on a large (perhaps huge) vocabulary – words for places, routes, techniques, individuals, and emotions. We have shown that Neandertal expertise was large

Blog: Playing by the book (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Pop-up, Moon / stars, Christiane Dorion, Beverley Young, Volcanoes, Royal Society Young People's Book Prize 2011, Seasons, Nonfiction, Science, Rain, Evolution, Planets, Water, Climate Change, Earthquakes, Add a tag

In my mini series reviewing the books shortlisted for the Royal Society Young People’s Book Prize 2011 next up is How The World Works by Christiane Dorion and Beverley Young

In my mini series reviewing the books shortlisted for the Royal Society Young People’s Book Prize 2011 next up is How The World Works by Christiane Dorion and Beverley Young

A pop-up book covering a wealth of ground, How The World Works is a tremendous introduction to topics as diverse as the solar system, evolution, plate tectonics, the water cycle, weather systems, photosynthesis and food chains.

Each double page spread covers one theme and explores it using exciting illustrations, illuminating paper engineering and and array of both key and intriguing facts presented in inviting, bite-sized portions. The illustrations have the rich colours and boldness you often see with Barefoot Books (though this is actually published by Templar). The short sections of text make this an undaunting book for young independent readers.

As well of plenty of flaps and tabs, there are lots of instances where the paper engineering really adds to your understanding of the topic under discussion. For example the big bang explosion is a brilliantly executed bit of fold out paper – simple, but very effective as it mimics an explosion. How the continents have drifted over time is beautifully illustrated with a flip book – by flipping the pages we can actually see the continents drifting from the supercontinent Pangaea about 200 million years ago to their current location.

Again, the paper engineering is put to exceptional use to illustrate what happens at different types of plate boundary; Andy Mansfield, the brains behind the pop-up aspect of this book, has created paper tricks that are not only great fun but, but informative and meaningful.

This book contains a subtle but consistent message about how we as humans are having an impact on the earth and what the consequences of our actions will be. In the section on carbon there are tips about how we can reduce our carbon footprint, whilst the pages devoted to how plants work draw attention to the problems caused by deforestation. In the discussion of ocean currents and tides we’re introduced to the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, “an area of plastic rubbish twice the size of Texas” floating in the Pacific ocean, whilst when exploring the the planets, the large quantity of space junk orbiting the earth is highlighted. Not only does this book tell us how the world works, it also makes us think about how it’s beginning to break down.

Display Comments Add a CommentBlog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: science, genetics, biology, evolution, horses, conservation, DNA, Thought Leaders, *Featured, Environmental & Life Sciences, genomes, Science & Medicine, danielle venton, genome biology and evolution, przewalski's horse, przewalski’s, makova, mitochondrial, Add a tag

By Danielle Venton

For millions of years, the stout, muscular Przewalski’s horse freely roamed the high grasslands of Central Asia. By the mid-1960s, these, the last of the wild horses, were virtually extinct: a result of hunting, habitat loss, and cross breeding with domestic horses.

Recovering from a tiny population of 12 individuals and only four purebred females, there are now nearly 2,000 Przewalski’s horses around the world. Once again, the light-colored horses, standing about 13 hands, or 1.3 meters, tall, are beginning to graze on the Asian steppe, thanks to captive breeding and reintroduction programs.

Protecting Przewalski’s horses, listed as critically endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature, will require far more than protecting their habitat. Understanding and safeguarding their genetic diversity is key, said Kateryna Makova, an evolutionary genomicist at Pennsylvania State University. In a new study (Goto et al. 2011), Makova and her colleagues Hiroki Goto, Oliver Ryder, and others report on the most complete genetic analysis of Przewalski’s horses to date, clarifying previous genetic analyses that were inconclusive.

Because Przewalksi’s horses are the only remaining wild horses, many people have hypothesized that they gave rise to modern domestic horses. The Australian Brumbies or the American Mustangs, sometimes referred to as wild horses, are actually feral domestic horses, adapted to life in the wild. Przewalski’s horses are not the direct progenitors of modern domestic horses, Makova and her colleagues conclude, but split approximately 0.12 Ma. Horses were likely domesticated several times on the Eurasian steppes. It is not known where and when the first event took place. Recent excavations in Kazakhstan indicate humans were using domestic horses as early as 5,500 years ago.

Przewalski’s horse and offspring

Przewalski’s horse and offspring

The team base their findings on a complete sequencing of the mitochondrial genome and a partial sequencing, between 1% and 2%, of the nuclear genome. They used one horse from each of the historical matrilineal lines. After processing the DNA samples with massively parallel sequencing technology, they compared the Przewalski’s horses to each other, to domestic Thoroughbred horses, and to an outgroup, the Somali wild ass.

Their results carry several implications for breeding strategies. Przewalski’s horses and domestic horses come from different evolutionary gene pools, so breeders should avoid crosses with domestic horses, they advise. Przewalski’s horses and domestic horses have a different number of chromosomes (66 for the former, compared with 64); yet their offspring are fertile (with 65 chromosomes). The hybrids are viable because they differ only by a centric fusion translocation, also called a Robertsonian translocation. The process of pairing chromosomes during meiosis is not disrupted. Cross breeding should be a last resort, if too few Przewalski’s horses are available. Their analysis also suggests that, since diverging, Przewalski’s and domestic horses have both retained joint ancestral genes and swapped genes between populations. One of the two current major blood lines, the “Prague” line, is known to have a Mongol pony as one of its ancestors. The other primary line, the “Munich” line, is believed to be pure. However, because the two groups have historically mixed, keeping “pure” Przewalski’s horses from Przewalski’s horses with known domestic horse contributions might not be necessary, the authors write.

Blog: Playing by the book (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: David McKean, Storytelling, Seasons, Nonfiction, Science, Evolution, Richard Dawkins, Fossils, Different perspectives, Moon / stars, Add a tag

Today National Non-Fiction Day is being celebrated across the UK, highlighting all that is brilliant about non fiction and showing that it’s not just fiction that can be read and enjoyed for pleasure.

Today National Non-Fiction Day is being celebrated across the UK, highlighting all that is brilliant about non fiction and showing that it’s not just fiction that can be read and enjoyed for pleasure.

My small contribution is a review of a family science book, The Magic of Reality by Richard Dawkins.

In this ambitious book, richly and imaginatively illustrated throughout by Dave McKean, Dawkins sets himself the task of answering some of the really big question of life, exactly the sort of questions you hear from the mouths of children including “Are we alone?” and “Why do bad things happen?”

In this ambitious book, richly and imaginatively illustrated throughout by Dave McKean, Dawkins sets himself the task of answering some of the really big question of life, exactly the sort of questions you hear from the mouths of children including “Are we alone?” and “Why do bad things happen?”

Over the course of 12 chapters Dawkins tackles these questions head on, also exploring key aspects of space, time and evolution along the way. He begins almost every chapter with examples of myths (from all over the world, from all different sorts of traditions) about the topic in question before moving on to explore the scientific explanation for the phenomenon under discussion.

This video gives a great summary of the book from Dawkins himself:

The Magic of Reality is no dry academic tract. Rather Dawkins takes on the role (almost) of intimate storyteller. He adopts an informal, colloquial manner focusing throughout the book on showing us what he calls the “poetic magic” of science, that which is “deeply moving, exhilarating: something that gives us goose bumps, something that makes us feel more alive.”

Dawkins’ friendly tone and his inclusion of stories about rainbows, earthquakes and the seasons make The Magic of Reality an eminently readable book, especially for readers with no or little background knowledge. There’s a lot of the pace, suspense and beauty you might associate with a great novel in Dawkins’ book. Indeed, Dawkins really seems to me to be trying to tell a story (albeit a true one) rather than simply sharing and contextualising a lot of scientific facts.

Perhaps a conscious decision to make the book read like a story is behind the decision not to include any footnotes, suggested further reading or bibliography. This I found frustrating; Dawkins’ succeeded in getting me curious, getting me asking questions about the issues he discusses, and although I would have liked to know more, he doesn’t provide any suggestion for where to go next. That said, the lack of references does help the book flow and feel quite unlike a hard hitting science book (though that is exactly what it is).

As a result of reading The Magic of Reality I got out our prisms and made rainbows with M and J - for them it really was magic to see the colours appear "from nowhere"

Dawkins’ storytelling approach also means that The Magic

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: archaeology, History, science, evolution, Anthropology, neanderthal, prehistoric, paleontology, fossils, homo, Humanities, missing link, fossil, Social Sciences, *Featured, australopithecus, berger, Classics & Archaeology, Science & Medicine, afarensis, erectus, john reader, lee berger, pretoria, sediba, palaeoanthropological, Add a tag

By John Reader A blaze of media attention recently greeted the claim that a newly discovered hominid species, , marked the transition between an older ape-like ancestor, such as Australopithecus afarensis, and a more recent representative of the human line, Homo erectus. As well as extensive TV, radio and front-page coverage, the fossils found by Lee Berger and his team at a site near Pretoria in South Africa featured prominently in National Geographic, with an illustration of the three species striding manfully across the page. In the middle, Au. sediba was marked with twelve points of similarity: six linking it to Au. afarensis on the left and six to H. erectus on the right. Though Berger did not explicitly describe Au. sediba as a link between the two species, the inference was clear and not discouraged. The Missing Link was in the news again.

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: mammals, united nations environment programme, *Featured, Environmental & Life Sciences, pollinators, Science & Medicine, international year of the bat, john altringham, altringham, gram, nature, science, environment, evolution, ecology, conservation, bats, Add a tag

By John D. Altringham 2011-12 is the International Year of the Bat sponsored by the United Nations Environment Programme. Yes, that’s right – we are devoting a whole year to these neglected and largely misunderstood creatures. Perhaps if I give you a few bat facts and figures you might begin to see why.

Blog: Mishaps and Adventures (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: evolution, Amulet Books design, jonathan auxier, peter nimble, Add a tag

About the book

Peter Nimble and His Fantastic Eyes is the utterly beguiling tale of a ten-year-old blind orphan who has been schooled in a life of thievery. One fateful afternoon, he steals a box from a mysterious traveling haberdasher—a box that contains three pairs of magical eyes. When he tries the first pair, he is instantly transported to a hidden island where he is presented with a special quest: to travel to the dangerous Vanished Kingdom and rescue a people in need. Along with his loyal sidekick—a knight who has been turned into an unfortunate combination of horse and cat—and the magic eyes, he embarks on an unforgettable, swashbuckling adventure to discover his true destiny

Blog: Litland.com Reviews! (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: ya, young adult, war, young adults, teaching, teen, review, science fiction, reading, family, kids, literature, fiction, ethics, God, teens, children's books, book reviews, books, Uncategorized, adventure, book, children's, character, homeschooling, apocalypse, classroom, children's lit, book club, sci fi, android, artificial intelligence, Bernard Beckett, apocalyptic, advanced reader interest, Summer/vacation reading, ethics/morality, teachers/librarians, science or nature, Adam & Eve, philosophy, homeschool, evil, evolution, creation, novella, post-apocalyptic, morals, good, intellectual, Genesis, consciousness, intelligence, Original sin, Quercus, man-made, Add a tag

Beckett, Bernard. (2006) Genesis. London: Quercus Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84724-930-2. Author age: young adult. Litland recommends age 14+.

Beckett, Bernard. (2006) Genesis. London: Quercus Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84724-930-2. Author age: young adult. Litland recommends age 14+.

Publisher’s description:

The island Republic has emerged from a ruined world. Its citizens are safe but not free. Until a man named Adam Forde rescues a girl from the sea. Fourteen-year-old Anax thinks she knows her history. She’d better. She’s sat facing three Examiners and her five-hour examination has just begun. The subject is close to her heart: Adam Forde, her long-dead hero. In a series of startling twists, Anax discovers new things about Adam and her people that question everything she holds sacred. But why is the Academy allowing her to open up the enigma at its heart? Bernard Beckett has written a strikingly original novel that weaves dazzling ideas into a truly moving story about a young girl on the brink of her future.

Our thoughts:

Irregardless of whether you are an evolutionist or creationist, if you like intellectual sci-fi you’ll love this book. How refreshing to read a story free from hidden agendas and attempts to indoctrinate its reader into a politically-correct mindset. And while set in a post-apocalyptic era, the world portrayed is one in which inhabitants have been freed from the very things that sets humans apart from all other creation, including man-made. Once engulfed in the story, the reader is drawn into an intellectual battle over this “difference” between man and man-made intelligence. The will to kill; the existence of evil. A new look at original sin. And a plot twist at the end that shifts the paradigm of the entire story.

Borrowing from the American movie rating scale, this story would be a PG. Just a few instances of profanity, it is a thought-provoking read intended for mature readers already established in their values and beliefs, and who would not make the error of interpreting the story to hold any religious metaphors. The “myth” of Adam and Art, original sin and the genesis of this new world is merely a structure familiar to readers, not a message. The reader is then free to fully imagine this new world without the constraints of their own real life while still within the constraints of their own value system.

Genesis is moderately short but very quick paced, and hard to put down once you’ve started! Thus it is not surprising to see the accolades and awards accumulated by Beckett’s book. The author, a New Zealand high school teacher instructing in Drama, English and Mathematics, completed a fellowship study on DNA mutations as well. This combination of strengths gives Genesis its intrigue as well as complexity. Yet it is never too theoretical as to exclude its reader. See our review against character education criteria at Litland.com’s teen book review section. And pick up your own copy in our bookstore!

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Science, environment, genetics, sheep, biology, chemistry, evolution, Darwin, DNA, *Featured, jonathan crowe, Physics & Chemistry, bioscience, sciwhys, Environmental & Life Sciences, genomes, organisms, origin of species, thicker, coated, mutation, thickness, Add a tag

This is the latest post in our regular OUPblog column SciWhys. Every month OUP editor and author Jonathan Crowe will be answering your science questions. Got a burning question about science that you’d like answered? Just email it to us, and Jonathan will answer what he can. Today: how do organisms evolve?

By Jonathan Crowe

The world around us has been in a state of constant change for millions of years: mountains have been thrust skywards as the plates that make up the Earth’s surface crash against each other; huge glaciers have sculpted valleys into the landscape; arid deserts have replaced fertile grasslands as rain patterns have changed. But the living organisms that populate this world are just as dynamic: as environments have changed, so too has the plethora of creatures inhabiting them. But how do creatures change to keep step with the world in which they live? The answer lies in the process of evolution.

Many organisms are uniquely suited to their environment: polar bears have layers of fur and fat to insulate them from the bitter Arctic cold; camels have hooves with broad leathery pads to enable them to walk on desert sand. These so-called adaptations – characteristics that tailor a creature to its environment – do not develop overnight: a giraffe that is moved to a savannah with unusually tall trees won’t suddenly grow a longer neck to be able to reach the far-away leaves. Instead, adaptations develop over many generations. This process of gradual change to make you better suited to your environment is called what’s called evolution.

So how does this change actually happen? In previous posts I’ve explored how the information in our genomes acts as the recipe for the cells, tissues and organs from which we’re constructed. If we are somehow changing to suit our environment, then our genes must be changing too. But there isn’t some mysterious process through which our genes ‘know’ how to change: if an organism finds its environment turning cold, its genome won’t magically change so that it now includes a new recipe for the growth of extra fur to keep it warm. Instead, the raw ‘fuel’ for genetic change is an entirely random process: the process of gene mutation.

In my last post, I considered how gene mutation alters the DNA sequence of a gene, and so alters the information stored by that gene. If you change a recipe when cooking, the end product will be different. And so it is with our genome: if the information stored in our genome – the recipe for our existence – changes, then we must change in some way too.

I mentioned above how the process of mutation is random. A mutation may be introduced when an incorrect DNA ‘letter’ is inserted into a growing chain as a chromosome is being copied: instead of manufacturing a stretch of DNA with the sequence ATTGCCT, an error may occur at the second position, to give AATGCCT. But it’s just as likely that an error could have been introduced at the sixth position instead of the second, with ATTGCCT becoming ATTGCGT. Such mutations are entirely down to chance.

And this is where we encounter something of a paradox. Though the mutations that occur in our genes to fuel the process of evolution do so at random, evolution itself is anything but random. So how can we reconcile this seeming conflict?

To answer this question, let’s imagine a population of sheep, all of whom have a woolly coat of similar thickness. Quite by chance, a gene in one of the sheep in the population picks up a mutation so that offspring of that sheep develop a slightly thicker coat. However, the thick-coated sheep is in a minority: most of the population carry the normal, non-mutated gene, and so have coats of normal thickness. Now, the sheep population live in a fairly tempera

Blog: Robin Brande (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Christians, evolution, Christianity, intelligent design, Teen Novels, controversy over evolution, Kenneth Miller, teaching evolution in schools, Life, Books, Reading, God, Young Adult Fiction, teen fiction, Writing, religion, science, Young Adult Novels, Add a tag

Yeah, I thought maybe you would.

I was interviewed recently by the very curious, very kind Bridgette Mongeon over here. Take a listen!

Blog: Mishaps and Adventures (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: evolution, Chad W. Beckerman, Sidekicks, Jack Ferraiolo, Amulet Books design, cheese touch, Jacket and Case, Add a tag

But after an embarrassing incident involving his too-tight spandex costume, plus some signs that Phantom Justice may not be the good guy he pretends to be, Scott begins to question his role. With the help of a fellow sidekick, once his nemesis, Scott must decide if growing up means being loyal or stepping boldly to the center of things.

After seeing Kick-Ass I really wanted this book to have a similar design approach. If not just totally ripping of the branding. Horrible to admit but true. My admiration would be followed soon with problems.

Only difference we didn't have actors so I enlisted Greg Horn to start work on sketches of our hero. Greg had just finished work on Jack's other book The Big Splash which was now in paperback. ( For more on the evolution of The Big Splash in hard cover by Nathan Fox click here)

Only difference we didn't have actors so I enlisted Greg Horn to start work on sketches of our hero. Greg had just finished work on Jack's other book The Big Splash which was now in paperback. ( For more on the evolution of The Big Splash in hard cover by Nathan Fox click here)

1 Comments on Evolution of the SIDEKICKS Jacket, last added: 4/20/2011

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: *Featured, Environmental & Life Sciences, charles taylor, secularism, creationist, darwin the writer, george levine, human evolution, darwin’s, History, Religion, Science, World, biology, atheist, Charles Darwin, controversial, einstein, Victorian, evolution, Darwin, intelligent design, secular, newton, Add a tag

By George Levine

How could Darwin still be controversial? We do not worry a lot about Isaac Newton, nor even about Albert Einstein, whose ideas have been among the powerful shapers of modern Western culture. Yet for many people, undisturbed by the law of gravity or by the theories of relativity that, I would venture, 99% of us don’t really understand, Darwin remains darkly threatening. One of the great figures in the history of Western thought, he was respectable and revered enough even in his own time to be buried in Westminster Abbey, of all places. He supported his local church; he was a Justice of the Peace; and he never was photographed as a working scientist, only as a gentleman and a family man. Yet a significant proportion of people in the English-speaking world vociferously do not “believe” in him.

Darwin is resisted not because he was wrong but because his ideas apply not only to the ants, and bees, and birds, and anthropoids, but to us. His theory is scary to many people because it seems to them it lessens our dignity and deprives our ethics of a foundation. The problem, of course, is that, like the theories of gravity and relativity, it is true.

At the heart of this very strange phenomenon there is a fundamental crisis of secularism. Secularism is not simply disbelief; it is not equivalent to atheism. Many supporters of secularism, like the distinguished Catholic philosopher, Charles Taylor, are believers. The most important aspect of secularism is that it is a condition of peaceful coexistence of otherwise antithetical faiths. In a secular state, diverse religions must agree that on matters of civil order and organization there is an institution to which they will all defer in what Taylor has described as “overlapping consensus.” They may disagree about God but they have to agree that in civil society they will adhere to the laws of the country.

But what happens when the overlapping consensus doesn’t overlap? This brings us to a very complicated problem: the authority of the specialist. In a democratic society, it is the responsibility of each of us to stay informed on issues that matter to the polity, and to make judgments, usually through established institutions, school boards, for example, or national elections. At the same time, our society usually sanctions the training of professionals, and forces them to undergo rigorous training, tests them to be sure of their qualifications.

Within professions, there will inevitably be learned and crucial squabbling and exploration, and new theories piled on top of old ones, or revising them. But these squabbles are part of what it is to be professional and they rarely reach the ears of the lay population. When science as an institution sanctions evolutionary theory (and squabbles about how it works), and its most distinguished practitioners insist that evolution is the foundation of all modern biology and by way of that theory make ever expanding discoveries about our health, a significant portion of the population accuse them of mere prejudice against doubters. People insist they don’t “believe” in Darwin, when they haven’t read him, don’t understand the theory to which they object, and seem unaware that evolutionary biology, though perhaps founded on Darwin, has long since made the nature of Darwin’s belief irrelevant to the validity of modern science.

Imagine a scientific community that allowed published papers to be reviewed by lay people, or simply published them without being reviewed by experts in the field. Imagine if The New England Journal of Medicine, or Nature, accepted papers which had not produced adequate evidence to make their cases, or distorted and misrepresented the evidence. Would that be a reasonable and democratic openi

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Math, evolution, Mathematics, pi, divide, sudoku, Jason Rosenhouse, Monty Hall Problem, ratio, *Featured, evolution blog, irrational number, circumference, evolutionblog, integer, rosenhouse, diameter, Add a tag

By Jason Rosenhouse

A recent satirical essay in the Huffington Post reports that congressional Republicans are trying to legislate the value of pi. Fearing that the complexity of modern geometry is hurting America’s performance on international measures of mathematical knowledge, they have decreed that from now on pi shall be equal to three. It is a sad commentary on American culture that you must read slowly and carefully to be certain the essay is just satire.

It has been wisely observed that reality is that which, when you stop believing in it, doesn’t go away. Scientists are especially aware of this, since it is sometimes their sad duty to inform people of truths they would prefer not to accept. Evolution cannot be made to go away by folding you arms and shaking your head, and the planet is warming precipitously regardless of what certain business interests claim to believe. Likewise, the value of pi is what it is, no matter what a legislative body might think.

That value, of course, is found by dividing the circumference of a circle by its diameter. Except that if you take an actual circular object and apply your measuring devices to it you will obtain only a crude approximation to pi. The actual value is an irrational number, meaning that it is a decimal that goes on forever without repeating itself. One of my middle school math teachers once told me that it is just crazy for a number to behave in such a fashion, and that is why it is said to be irrational. Since I rather liked that explanation, you can imagine my disappointment at learning it was not correct.

In this context, the word “irrational” really just means “not a ratio.” More specifically, it is not a ratio of two integers. You see, if you divide one integer by another there are only two things that can happen. Either the process ends or it goes on forever by repeating a pattern. For example, if you divide one by four you get .25, while if you divide one by three you get .3333… . That these are the only possibilities can be proved with some elementary number theory, but I shall spare you the details of how that is done. That aside, our conclusion is that since pi never ends and never repeats, it cannot be written as one integer divided by another.

Which might make you wonder how anyone evaluated pi in the first place. If the number is defined geometrically, but we cannot hope to measure real circles with sufficient accuracy, then why do we constantly hear about computers evaluating its first umpteen million digits? The answer is that we are not forced to define pi in terms of circles. The number arises in other contexts, notably trigonometry. By coupling certain facts about right triangles with techniques drawn from calculus, you can express pi as the sum of a certain infinite series. That is, you can find a never-ending list of numbers that gets smaller and smaller and smaller, with the property that the more of the numbers you sum the better your approximation to pi. Very cool stuff.

Of course, I’m sure we all know that pi is a little bit larger than three. This means that any circle is just over three times larger around than it is across. The failure of most people to be able to visualize this leads to a classic bar bet. Take any tall, thin, drinking glass, the kind with a long stem, and ask the person sitting nearest you if its height is greater than its circumference. When he answers that it is, bet him that he is wrong. Optically, most such glasses appear to be much taller than they are fat, but unless your specimen is very tall and very thin you will win the bet every time. The circumference is more than three times larger than the diameter at the top of the glass. A vessel so proportioned that this length is nonetheless smal

Blog: Ginger Pixels (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: sketch, digital, Ginger Nielson, Painter, evolution, Add a tag

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: evolution, Religion, American History, morals, A-Featured, Western Religion, enoch, Psychology, Rossano, Add a tag

Matt J. Rossano is head of the Psychology department at Southeastern Louisiana University. His new book, Supernatural Selection: How Religion Evolved, presents an evolutionary history of religion, drawing together evidence from a wide range of disciplines to show the valuable adaptive purpose served by systemic belief in the supernatural. In the excerpt below, Rossano reminds us of the comfort of believing in things that may be irrational.

In April 2008, the phone rang at the home of Howard Enoch III. It was the U.S. Army. Howard’s father would finally be coming home. Sixty-three years earlier, in the waning days of World War II, Second Lieutenant Howard “Cliff” Enoch Jr. climbed into his P-51D Mustang fighter for a mission over Halle, Germany. He never returned. When the Iron Curtain enveloped the site where Enoch’s plane went down, the army declared his remains “unrecoverable.” But dedicated members of the U.S. Army’s Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command refused to give up on Cliff Enoch. In 2004, their review of crash sites in the former East Germany revealed suspicious plane fragments near the village of Doberschutz. Two years later, an onsite excavation team found what appeared to be human remains. The remains were flown to a laboratory in Hawaii for DNA analysis while the army continued to study the crash-site evidence. In the end it led to the phone call – and a burial with full honors at Arlington National Cemetery.

“Remarkable” is how Howard Enoch described the events of that spring. “I will now have a place…to know where he is…to be close to him,” he said. “Before this, I always thought of my father as a young man, sitting in a beautiful pasture in Germany, waiting for someone to bring him home – and that is what happened.” Commenting on the extraordinary effort the military expended in retrieving and identifying the remains, army spokesman Johnnie Webb explained that it was important for people to know that the “creed and tradition” in the military is to “leave no one behind.” The military, he said, would always do their utmost to “honor that promise.”

A bittersweet story. But most would agree that it ends as it should. It is right and good that the brave young soldier be returned to his home, his country, his family. The human desire to keep loved ones near, even in death, hardly needs an explanation or justification. Yet very little of this story can be defended as reasonable. Cold logic would correctly conclude that it is of no consequence where Cliff Enoch’s remains are buried, or even whether they are ever conclusively identified. After 60 years there’s no doubt that he is dead. His loved ones have gone on with their lives, and the skeletal remnants care nothing about the ground under which they lie. From a practical standpoint, a backyard cross is as good a remembrance place for the downed pilot as a cemetery plot. And wouldn’t the army’s limited resources be better spend on increased health and education benefits for veterans or better housing for military families, rather than on the retrieval of a few old bones?

Howard Enoch was welcoming back a man whom he had never known. Now 63 years old, he was born after his father Cliff was shot down. The fallen hero was but a picture on the wall, a story only rarely broached, more a myth and a spirit than a man. But is it fair to say that Howard and this spirit were strangers to each other? Was there no relationship here at all? The fact that it just feels wrong – cruel, even – to simply let Cliff Enoch’s bones lie anonymously in

Blog: Playing by the book (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Fish, Evolution, Water, Beaches, Sealife, Chris Wormell, Add a tag

With J’s current fish obsession we’re on the look out for books about fish at the moment. One Smart Fish by Chris Wormell was a chance find when we were visiting the Natural History Museum a few weeks back – it’s not a book I had previously heard of – but it’s now definitely one of J’s favourites so far this year.

One Smart Fish tells the story of a crucial evolutionary step – how many millions of years ago some fish left the sea and began life on land. It’s a big topic but through the use of stunning illustrations and perfectly pitched text, liberally sprinkled with humour, Wormell has written the ideal book for introducing the idea of evolution to young children.

Many pages are densely packed with a range of fish of all shapes, sizes, colours and texture, whilst the penultimate double page spread has a hugely detailed expanse of creatures surging out across the land showing the evolution from fish to – eventually – human beings. Like the earlier pictures of fish we can’t help pouring over the illustrations and playing “I spy” – just like we do when reading some other much enjoyed books of ours – Anno’s Journey or The History Puzzle.