new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: novel, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 26 - 50 of 401

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: novel in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

.png.jpg?picon=4257)

By: Diana Hurwitz,

on 6/13/2014

Blog:

Game On! Creating Character Conflict

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

fiction,

novel,

editing,

writing,

grammar,

revision,

subject,

nouns,

howto,

tense,

verb,

sentencestructure,

Add a tag

When revising, it is important to look at each sentence for subject-verb agreement. This is one of those skills that comes naturally over time.

There are a few tricky circumstances to double check.

1) A singular subject requires a singular verb. A plural subject requires a plural verb with a few exceptions.

I sing. You sing. We all sing for ice cream.

The little girls all sang for their supper.

2) If the subject has two singular nouns joined with and use a plural verb.

Dick and Jane are ready to go home.

3) If the subject has two singular nouns joined with or or nor, use a singular verb.

Neither Dick nor Jane is ready to go home.

4) If the subject has a singular noun joined to a plural noun by or or nor, the verb should agree with whichever noun comes last.

Neither Dick nor his friends want to play catch outside.

Either Sally or Jane visits everyday.

5) The contractions doesn't (does not) and wasn't (was not) are always used with a singular subject.

Dick doesn’t want to go.

6) The contractions don't (do not) and weren't (were not) are always used with a plural subject. The exception to this rule is I and you require don't.

We don’t want to go with Jane.

You don’t believe me.

I don’t want to go home yet.

7) When a modifying phrase comes between the subject and the verb, it does not change the agreement. The verb always agrees with the subject, not the modifying phrase.

Dick, as well as his friends, hopes the Colts win.

Jane, as well as Sally and Dick, hopes the meeting will be over soon.

8) Distributives are singular and need a singular verb: anybody, anyone, each, each one, either, everybody, everyone, neither, no, one, nobody, somebody, someone.

Each of them will go there someday.

Nobody knows Dick is here.

Either way works.

Neither option is viable.

9) Plural nouns functioning as a single unit, such as mathematics, measles, and mumps, require singular verbs. An exception is the word dollars. When used to reference an amount of money, dollars requires a singular verb; but when referring to the bills themselves, a plural verb is required.

Five thousand dollars would suffice.

Dollars are easier to exchange than Euros.

10) Another exception is nouns with two parts. They can usually be prefaced with a pair of and require a plural verb: glasses, pants, panties, scissors, or trousers. Why they are considered pairs is another question.

Dick's trousers are worn.

Jane's scissors are missing.

11) When a sentence begins with the verb phrases there is and there are and they are followed by the subject, the verb must agree with the subject that follows.

There are many who would agree with you.

There is the question of who goes first.

12) A subject can be modified by a phrase that begins with: accompanied by, as well as, as with, in addition to, including, or together with. However, this does not modify the plurality of the subject. If the subject is single, it requires a singular verb. If the subject is plural, it requires a plural verb.

Dick, accompanied by his wife Jane, will arrive in ten minutes.

Everything, including the kitchen sink, is up for auction.

The cousins, together with their dog, are going to be here for a week.

Revision Tips

? This step needs to be done sentence by sentence and is best done on a printed copy. Identify the complicated sentences.

? Underline the subject and verb. Do they agree? If not, correct them.

? Make sure the modifying phrases are used correctly.

For all of the revision tips on verbs and other revision layers, pick up a copy of:

I like anniversaries, especially when they concern my illustrations! So here's another fond memory - this year is the 30th anniversary of the publication of Elsie Locke's A Canoe in the Mist.

|

| Cover of the 1st edition |

|

| The Waka Wairua. Title Page vignette |

This was my third commissioned book contract, after Jeremy Strong's

Fatbag (A & C Black) and Roger Collinson's

Get Lavinia Goodbody! (Andersen Press), both first released in 1983. Like them, it was a commission for black and white text drawings to a novel. Unlike those titles however, both of which were fun, humorous books requiring comic drawings, this new commission was a dramatised narrative of real events during the

catastrophic 1886 eruption of Mount Tarawera in New Zealand.

|

| McCrae's Rotomahana Hotel in Te Wairoa. |

|

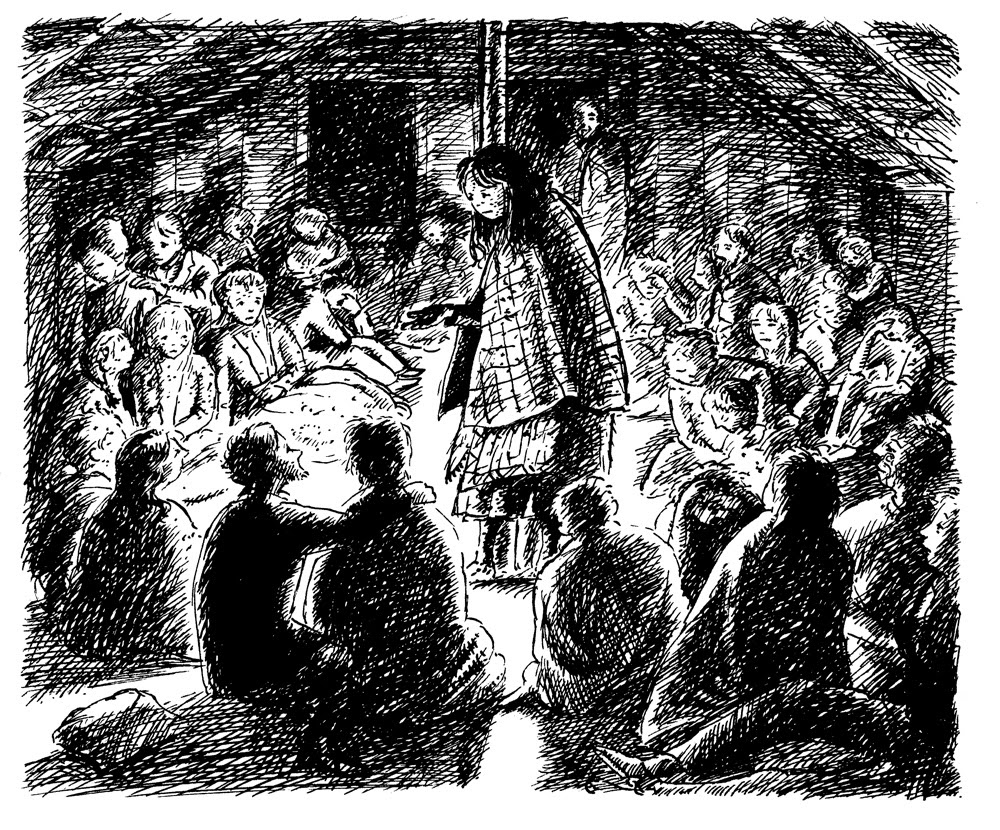

| Lillian meets Mattie |

Canoe in the Mist follows the story of two girls during the eruption. Lillian Perham lives in the village of

Te Wairoa with her widowed mother, where western tourists flock to view the famous

pink and white terraces, natural stairs of silica pools on Lake

Rotomahana. Set in a volcanic wonderland often described as the 8th wonder of the world, Lillian only has chance to see the terraces herself when she befriends Mattie, the daughter of visiting English tourists. But the day they set off for Rotomahana the waters of the lake are mysteriously lifted by a tidal wave, the tohunga sage of the local maori village propheses disaster, and a mysterious ghostly apparition of a canoe, waka wairua, is seen on the lake.  |

| The Terraces (unused version). This 1/2 page drawing was re-drawn as a full page illustration for the final book (artwork now lost) |

That night the volcano violently erupts, followed soon after by fissures underneath the lake that destroy the terraces and turn Lake Rotomahana into an explosion of steam and mud, burying the Maori villages of Moura and Te Ariki, killing 153 people. Caught in a deluge of debris and mud, the girls, parents and villagers struggle to escape a world that has been torn apart.

|

| The first eruption |

The commission came at the very end of 1983 from Jonathan Cape publishers, at that time based in Bedford Square, long before they were absorbed by Random House, I think it was simply a case of showing my work in their office at the right time. It was a fortuitous commission, coming soon after I'd moved to London, I threw myself into sketches straight away.

|

| Character studies for Lillian, Mattie and Sophia (unused) |

|

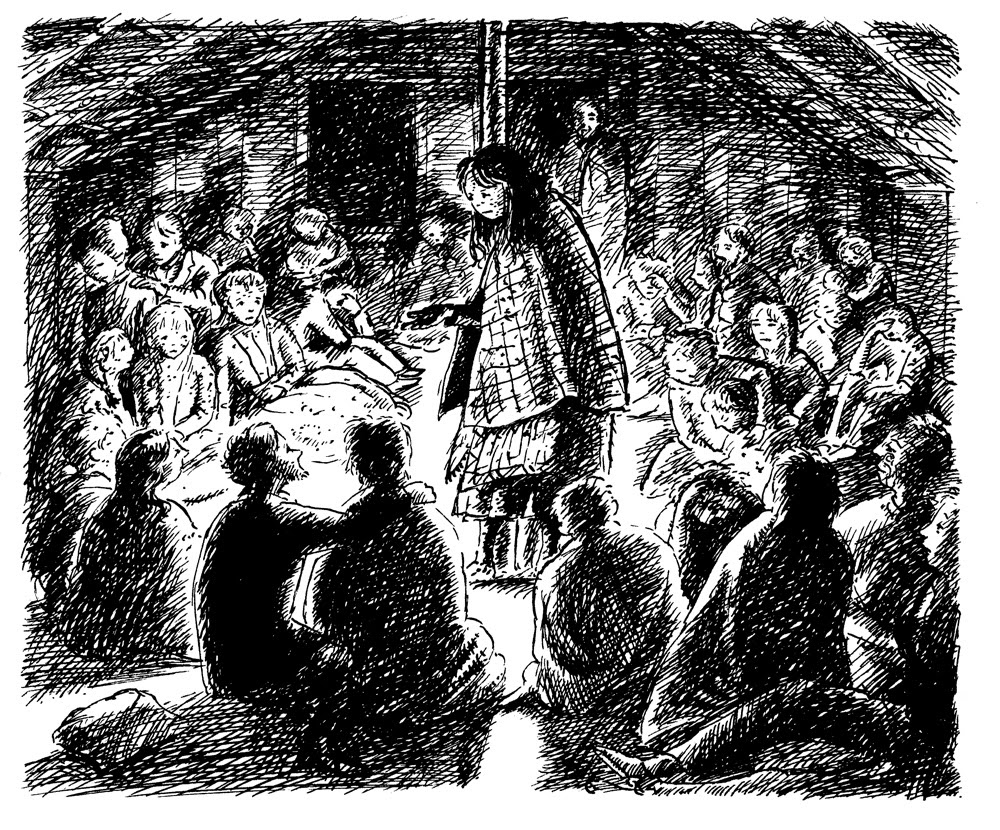

| Visit to Hinemihi, the Maori meeting hall |

This was of course, long before the internet, so finding accurate reference material was going to be a struggle. Despite the book being a historical topic my editor was unable to provide visual references, I knew very little about New Zealand in the 1880's, and despite my suggestion Jonathan Cape wasn't about to fly me out there to do some ground research! However my

local library in Crouch End was a tremendous help, especially on information on Maori culture. The publisher also passed on my queries to the author in New Zealand, who after a short while very kindly sent me a package of photos and cuttings outlining the region today and before the earthquake.

|

| Tuhoto, the village sage |

What I didn't realise until much later on however, was just how deeply embedded in the background of the book the author was.

Elsie Locke (1912-2001), writer, feminist, historian and peace campaigner, is today recognised as one of the most important figures of New Zealand culture of the last century. Although she passed away in 2001, the

Elsie Locke Memorial Trust continues to promote her life, work and writings, and sponsors an annual competition for young writers in New Zealand.

I was a young struggling illustrator in London, for me New Zealand seemed a very remote and exotic place at the time, and yet the correspondence I exchanged with Elsie not only brought the region to life visually, it helped greatly to spark my imagination.

|

| Before the eruption guests discuss the unusual signs |

The drawings were largely crafted at my humble abode in London - this was just before I joined a studio so I was working on the kitchen table in a shared house. One morning in a curious parallel to the book's plot I almost lost everything. I walked into the kitchen and found it awash with water - one of my house mates had run a bath upstairs then completely forgot about it - the bath overflowed, water poured through the ceiling into the kitchen beneath, the table was drenched, my drawings were soaked. This in itself wasn't quite as much of a disaster as it sounds - indian ink is waterproof after all, but my flatmate had compounded the problem by pinning each wet drawing to the washing line with rusty old clothes pegs, which made horrible indelible brown marks and ripped the sodden paper.

|

| The hotel ablaze |

So, many of the drawings were re-drawn from scratch, some of them several times, with time running out I finished the book in the much safer and more comfortable environment of my parent's house in Norwich. But eventually all was done, the artwork was delivered.

|

| Rescuing a surviving horse from the mud |

This book was a major watershed for me (excuse the pun!). With the painful experience of my own little disaster in the kitchen flood I was desperate to find somewhere else to work, so straight after completing the artwork for

A Canoe in the Mist I joined with my old friend, designer Andy Royston and co-founded Facade Art Studios in Crouch End, right next to the library that had been so helpful in my research.

|

| Sophia addresses the survivors. This was the finished version intended for the book, but a mix-up led the designer to use an inferior preparatory version instead! |

Looking back at the drawings now they're clearly an early work with some rough edges, also there were a couple of slips by the designer too - one drawing was reproduced back-to-front, in the case of another an inferior first version was printed instead of the intended drawing. Were I to illustrate the book again now I'd handle some drawings differently, and I certainly would not have given the art director more than one version of each drawing! But these were learning times, I was just beginning to find my feet as an illustrator, and to this day I'm proud of my involvement with the book, and the writer.

A Canoe in the Mist was

re-issued by Collins in their Modern Classics series in 2005, though, due to constraints of the series, sadly without any illustrations.

|

| The families struggle through a deluge of mud |

|

| Survivors |

Interestingly, though the Pink and White Terraces were thought to be utterly destroyed and the area left largely uninhabitable, in 2011

parts of the Pink Terraces were re-discovered still in existence, hidden under thick layers of mud.

|

| The final illustration - escape through a devastated landscape |

And there lies a strange parallel - I assumed my old drawings for the book had also been lost long ago, but recently was amazed to discover them in my dad's loft, including some sketches and alternative versions that never made it into the final book. So for those who don't know

A Canoe in the Mist, or may only have read the unillustrated Collins Classic edition, here they are!

Improve your novel with James Scott Bell’s Conflict & Suspense.

Order Now >>

My neighbor John loves to work on his hot rod. He’s an automotive whiz and tells me he can hear when something is not quite right with the engine. He doesn’t hesitate to pop the hood, grab his bag of tools and start to tinker. He’ll keep at it until the engine sounds just the way he wants it to.

That’s not a bad way to think about dialogue. We can usually sense when it needs work. What fiction writers often lack, however, is a defined set of tools they can put to use on problem areas.

So here’s a set—my seven favorite dialogue tools. Stick them in your writer’s toolbox for those times you need to pop the hood and tinker with your characters’ words.

#1 LET IT FLOW.

When you write the first draft of a scene, let the dialogue flow. Pour it out like cheap champagne. You’ll make it sparkle later, but first you must get it down on paper. This technique will allow you to come up with lines you never would have thought of if you tried to get it right the first time.

In fact, you can often come up with a dynamic scene by writing the dialogue first. Record what your characters are arguing about, stewing over, revealing. Write it all as fast as you can. As you do, pay no attention to attributions (who said what). Just write the lines.

Once you get these on the page, you will have a good idea of what the scene is all about. And it may be something different than you anticipated, which is good. Now you can go back and write the narrative that goes with the scene, and the normal speaker attributions and tags.

I have found this technique to be a wonderful cure for writer’s fatigue. I do my best writing in the morning, but if I haven’t done my quota by the evening (when I’m usually tired), I’ll just write some dialogue. Fast and furious. It flows and gets me into a scene.

With the juices pumping, I find I’ll often write more than my quota. And even if I don’t use all the dialogue I write, at least I got in some practice.

[Learn the 5 Essential Story Ingredients You Need to Write a Better Novel]

#2 ACT IT OUT.

Before going into writing, I spent some time in New York, pounding the pavement as an actor. While there, I took an acting class that included improvisation. Another member of the class was a Pulitzer Prize–winning playwright. When I asked him what he was doing there, he said improvisational work was a tremendous exercise for learning to write dialogue.

I found this to be true. But you don’t have to join a class. You can improvise just as easily by doing a Woody Allen.

Remember the courtroom scene in Allen’s movie Bananas? Allen is representing himself at the trial. He takes the witness stand and begins to cross-examine by asking a question, running into the witness box to answer, then jumping out again to ask another question.

I am suggesting you do the same thing (in the privacy of your own home, of course). Make up a scene between two characters in conflict. Then start an argument. Go back and forth, changing your actual physical location. Allow a slight pause as you switch, giving yourself time to come up with a response in each character’s voice.

Another twist on this technique: Do a scene between two well-known actors. Use the entire history of movies and television. Pit Lucille Ball against Bela Lugosi, or have Oprah Winfrey argue with Bette Davis. Only you play all the parts. Let yourself go.

And if your local community college offers an improvisation course, give it a try. You might just meet a Pulitzer Prize winner.

#3 SIDESTEP THE OBVIOUS.

One of the most common mistakes aspiring writers make with dialogue is creating a simple back-and-forth exchange. Each line responds directly to the previous line, often repeating a word or phrase (an “echo”). It looks something like this:

“Hello, Mary.”

“Hi, Sylvia.”

“My, that’s a wonderful outfit you’re wearing.”

“Outfit? You mean this old thing?”

“Old thing! It looks practically new.”

“It’s not new, but thank you for saying so.”

This sort of dialogue is “on the nose.” There are no surprises, and the reader drifts along with little interest. While some direct response is fine, your dialogue will be stronger if you sidestep the obvious:

“Hello, Mary.”

“Sylvia. I didn’t see you.”

“My, that’s a wonderful outfit you’re wearing.”

“I need a drink.”

I don’t really know what is going on in this scene (incidentally, I’ve written only these four lines of dialogue). But I think you’ll agree this exchange is immediately more interesting and suggestive of currents beneath the surface than the first example. I might even find the seeds of an entire story here.

You can also sidestep with a question:

“Hello, Mary.”

“Sylvia. I didn’t see you.”

“My, that’s a wonderful outfit you’re wearing.”

“Where is he, Sylvia?”

Hmm. Who is “he”? And why should Sylvia know? The point is there are innumerable directions in which the sidestep technique can go. Experiment to find a path that works best for you. Look at a section of your dialogue and change some direct responses into off-center retorts. Like the old magic trick ads used to say, “You’ll be pleased and amazed.”

[Understanding Book Contracts: Learn what’s negotiable and what’s not.]

#4 CULTIVATE SILENCE.

A powerful variation on the sidestep is silence. It is often the best choice, no matter what words you might come up with. Hemingway was a master at this. Consider this excerpt from his short story “Hills Like White Elephants.” A man and a woman are having a drink at a train station in Spain. The man speaks:

“Should we have another drink?”

“All right.”

The warm wind blew the bead curtain against the table.

“The beer’s nice and cool,” the man said.

“It’s lovely,” the girl said.

“It’s really an awfully simple operation, Jig,” the man said. “It’s not really an operation at all.”

The girl looked at the ground the table legs rested on.

“I know you wouldn’t mind it, Jig. It’s really not anything. It’s just to let the air in.”

The girl did not say anything.

In this story, the man is trying to convince the girl to have an abortion (a word that does not appear anywhere in the text). Her silence is reaction enough.

By using a combination of sidestep, silence and action, Hemingway gets the point across through a brief, compelling exchange. He uses the same technique in this well-known scene between mother and son in the story “Soldier’s Home”:

“God has some work for every one to do,” his mother said. “There can’t be no idle hands in His Kingdom.”

“I’m not in His Kingdom,” Krebs said.

“We are all of us in His Kingdom.”

Krebs felt embarrassed and resentful as always.

“I’ve worried about you so much, Harold,” his mother went on. “I know the temptations you must have been exposed to. I know how weak men are. I know what your own dear grandfather, my own father, told us about the Civil War and I have prayed for you. I pray for you all day long, Harold.”

Krebs looked at the bacon fat hardening on the plate.

Silence and bacon fat hardening. We don’t need anything else to catch the mood of the scene. What are your characters feeling while exchanging dialogue? Try expressing it with the sound of silence.

#5 POLISH A GEM.

We’ve all had those moments when we wake up and have the perfect response for a conversation that took place the night before. Wouldn’t we all like to have those bon mots at a moment’s notice?

Your characters can. That’s part of the fun of being a fiction writer. I have a somewhat arbitrary rule—one gem per quarter. Divide your novel into fourths. When you polish your dialogue, find those opportunities in each quarter to polish a gem.

And how do you do that? Like a diamond cutter, you take what is rough and tap at it until it is perfect. In the movie The Godfather, Moe Greene is angry that a young Michael Corleone is telling him what to do. He might have said, “I made my bones when you were in high school!” Instead, screenwriter Mario Puzo penned, “I made my bones when you were going out with cheerleaders!” (In his novel, Puzo wrote something a little racier). The point is you can take almost any line and find a more sparkling alternative.

Just remember to use these gems sparingly. The perfect comeback grows tiresome if it happens all the time.

#6 EMPLOY CONFRONTATION.

Many writers struggle with exposition in their novels. Often they heap it on in large chunks of straight narrative. Backstory—what happens before the novel opens—is especially troublesome. How can we give the essentials and avoid a mere information drop?

Use dialogue. First, create a tension-filled scene, usually between two characters. Get them arguing, confronting each other. Then have the information appear in the natural course of things. Here is the clunky way to do it:

John Davenport was a doctor fleeing from a terrible past. He had been drummed out of the profession for bungling an operation while he was drunk.

Instead, place this backstory in a scene in which John is confronted by a patient who is aware of the doctor’s past:

“I know who you are,” Charles said.

“You know nothing,” John said.

“You’re that doctor.”

“If you don’t mind I—”

“From Hopkins. You killed a woman because you were soused. Yeah, that’s it.”

And so forth. This is a much underused method, but it not only gives weight to your dialogue, it increases the pace of your story.

[Here's how to turn traumatic experiences into fuel for your writing.]

#7 DROP WORDS.

This is a favorite technique of dialogue master Elmore Leonard. By excising a single word here and there, he creates a feeling of verisimilitude in his dialogue. It sounds like real speech, though it is really nothing of the sort. All of Leonard’s dialogue contributes to characterization and story.

Here is a standard exchange:

“Your dog was killed?

“Yes, run over by a car.”

“What did you call it?”

“It was a she. I called her Tuffy.”

This is the way Leonard did it in Out of Sight:

“Your dog was killed?”

“Got run over by a car.”

“What did you call it?”

“Was a she, name Tuffy.”

It sounds so natural, yet is lean and meaningful. Notice it’s all a matter of a few words dropped, leaving the feeling of real speech.

As with any technique, there’s always a danger of overdoing it. Pick your spots and your characters with careful precision and focus, and your dialogue will thank you for it later.

Using tools is fun when you know what to do with them. I guess that’s why John, my neighbor, is always whistling when he works on his car. You’ll see results in your fiction—and have fun, too—by using these tools to make your dialogue sound just right.

Start tinkering.

Thanks for visiting The Writer’s Dig blog. For more great writing advice, click here.

*********************************************************************************************************************************

Brian A. Klems is the online editor of Writer’s Digest and author of the popular gift book Oh Boy, You’re Having a Girl: A Dad’s Survival Guide to Raising Daughters.

Brian A. Klems is the online editor of Writer’s Digest and author of the popular gift book Oh Boy, You’re Having a Girl: A Dad’s Survival Guide to Raising Daughters.

Follow Brian on Twitter: @BrianKlems

Sign up for Brian’s free Writer’s Digest eNewsletter: WD Newsletter

" Saucy is a real character dealing with real stuff—hard stuff that doesn’t have easy answers, not in real life and not in fairy tales, either. This is a really compelling and ultimately hopeful story. Highly recommended."

– Debby Dahl Edwardson, National Book Award finalist and author of

My Name is Not Easy

Read a sample chapter.

We don’t write in a vacuum. Your story is in the context of the whole of literature, and specifically, the literature of your genre. How does your story add to, change, enhance the conversation?

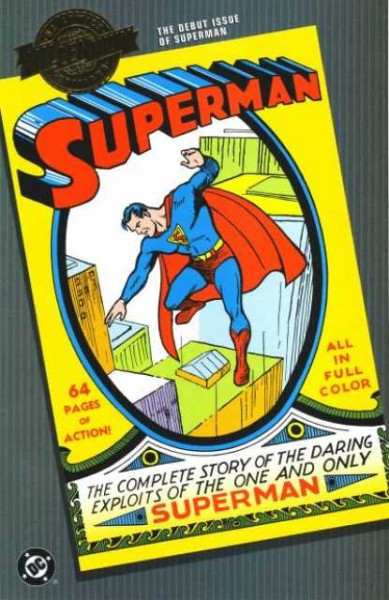

Superman No. 1, Millennium Edition, a reprint of the first ever Superman Comic.

This question was brought home to me as I picked up my son’s comic book. It’s a reproduction of the original Superman comic book from 1938 (Millennium Edition, Superman 1, December 2000, originally published as Superman No. 1 Summer 1939). Wow! It’s bad. Really.The characterization, the back story, indeed the characters are all pretty stale and cliched. But that’s my evaluation from this time, from 2014.

The reproduction starts with an introduction to the comic:

Until 1938 most comics were usually filled with reprint material spotlighting the more successful newspaper strips of the day. And while ACTION COMICS was one of the first titles filled with original material–created from scratch for less money than it would have cost to reprint existing comic strips–few could have been ready for the sensation its cover-featured star would cause! ACTION #1 spotlighted the debut performance of the world’s first–and still foremost–superhero: SUPERMAN!

This puts the fist story of Superman into context. No wonder there’s no mention of Jor-el and the struggle on Krypton (which is expounded in recent films). Mr. and Mrs. Kent are just described as an elderly couple. Clark’s first exploit is to prevent a lynching, then catch a singer who “rubbed out” her lover for cheating on her, and then to stop an incident of domestic violence. Not the stuff of super-fame. The stakes are low–Superman isn’t saving the world here.

But in the context of comics that just reprinted comic strips from the newspapers, Wow! Again, Wow! This was great stuff.

Two things strike me here: First, Superman had a humble beginning. Too often today, humble beginnings are overlooked or not allowed to even see the light of day. We want a fully developed story, with super-hero characters. But these type characters often need a small beginning. They develop over time as the story becomes part of the culture and join the conversations of our time. If the story captures any part of our imagination, they will become part of the conversation and the characters, the story, the plotlines–everything–will grow and develop. I wish there was a way to let more stories do this, to begin small, to join the conversations and to develop. Witness the Superman legends today, with rich back story on his parents, his struggles to fit into Earth, the dangers from other Kryptonite survivors, his love life with Lois Lane and so on.

Second, Superman was a product of 1938. His story joined the conversation of his time. His first act was to prevent a lynching. Would that speak to today’s audience? No. Domestic violence? Shrug. We’ve seen so many stories that are much better than the nine panels devoted to this small subplot.

How Does Your Story Join the Conversation

Today, werewolves and zombies are having a rich conversation in our culture. You’d have to be an ostrich to know nothing at all of the influx of werewolves stories. Well–if truth be told, I am almost an ostrich on these two subjects. Until I read Red Moon by Benjamin Percy, who brings the werewolf story alive in new ways. (Actually, I’m linking here to the audio version because the author narrates his own story in an impossibly deep voice that is fascinating to listen to.) This is no “Cry Wolf” story, but a fascinating look at how the ancient legend could possibly affect our lives today; and it’s told with impeccable prose that fascinated me with its amazing storytelling.

I shunned the whole zombie thing until my hairdresser raved about “Warm Bodies,” a movie that took Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet and updated it with zombies. Really? You could DO that? In other words, zombies were joining the conversation about romance and love. How do the things that separate men and women affect our lives? Can love really change things?

In other words, it’s almost impossible to live in today’s world and not know something about zombies and werewolves. The literary conversation is littered with these conversations that make connections which weave in and out of the canon of English and Western literature.

Saucy and Bubba. A Contemporary Hansel and Gretel Story.

I call my recent story,

SAUCY AND BUBBA, a contemporary Hansel and Gretel story because it puts it into a certain context: the discussion of step-mothers and how they treat the step-children. Mine is a twist on the old story–of course! In fact, it MUST be a twist on the old story, or it adds nothing to the conversation. Why would you rehash the same thing again. One reviewer said, “When a story can get me to even start to like the antagonist – like Saucy and Bubba does here – I know there’s a good book in my hands.” That’s what I wanted, a more nuanced look at the step-mother. I wanted the reader to have sympathy for her, even as they condemn her actions.

It’s like the original Superman comic: in today’s terms, it’s cliched. But it was hugely original for it’s time. It added to the conversations about justice and law-enforcement in interesting ways. If I simply repeated the Hansel and Gretel fairy tale, it would be a flop. Instead, we must think about how our stories fit into the context of our times. We must strive to join the conversation and to have something to add to the conversation. How can we add something different, interesting, conflicting, nuanced and so on? How are you enriching the conversation? How are you changing the conversation?

How does YOUR story join the conversation of our times?

By: Guest Column,

on 5/9/2014

Blog:

Guide to Literary Agents

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

fiction,

novel,

writing basics,

Steven James,

What's New,

Writing Genres,

Writing Your First Draft,

Complete 1st Draft,

Haven't Written Anything Yet, Writing for Beginners,

How to Improve Writing Skills,

How to Start Writing a Book, 1st Chapter,

Brian Klems' The Writer's Dig,

Add a tag

Like Steven James’ advice?

Then you’ll love his book,

Story Trumps Structure

Order now >>

Imagine that I’m telling you about my day and I say, “I woke up. I ate breakfast. I left for work.”

Is that a story? After all, it has a protagonist who makes choices that lead to a natural progression of events, it contains three acts and it has a beginning, a middle and an end—and that’s what makes something a story, right?

Well, actually, no.

It’s not.

—By Steven James

My description of what I did this morning—while it may meet those commonly accepted criteria—contains no crisis, no struggle, no discovery, no transformation in the life of the main character. It’s a report, but it’s not a story.

Over the years as I’ve taught at writing conferences around the world, you should see some of the looks I’ve gotten when I tell people to stop thinking of a story in terms of its structure. And it’s easy to understand why.Spend enough time with writers or English teachers and you’ll hear the dictum that a story is something that has a beginning, middle and end. I know that the people who share this definition mean well, but it’s really not a very helpful one for storytellers. After all, a description of a pickle has a beginning, a middle and an end, but it’s not a story. The sentence, “Preheat the oven to 450 degrees,” has those basic elements, but it’s not a story either.

So then, what is a story?

Centuries ago, Aristotle noted in his book Poetics that while a story does have a beginning, a middle and an ending, the beginning is not simply the first event in a series of three, but rather the emotionally engaging originating event. The middle is the natural and causally related consequence, and the end is the inevitable conclusive event.

In other words, stories have an origination, an escalation of conflict, and a resolution.

Of course, stories also need a vulnerable character, a setting that’s integral to the narrative, meaningful choices that determine the outcome of the story, and reader empathy. But at its most basic level, a story is a transformation unveiled—either the transformation of a situation or, most commonly, the transformation of a character.

Simply put, you do not have a story until something goes wrong.

At its heart, a story is about a person dealing with tension, and tension is created by unfulfilled desire. Without forces of antagonism, without setbacks, without a crisis event that initiates the action, you have no story. The secret, then, to writing a story that draws readers in and keeps them turning pages is not to make more and more things happen to a character, and especially not to follow some preordained plot formula or novel-writing template. Instead, the key to writing better stories is to focus on creating more and more tension as your story unfolds.

Understanding the fundamentals at the heart of all good stories will help you tell your own stories better—and sell more of them, too. Imagine you’re baking a cake. You mix together certain ingredients in a specific order and end up with a product that is uniquely different than any individual ingredient. In the process of mixing and then baking the cake, these ingredients are transformed into something delicious.

That’s what you’re trying to do when you bake up a story.

So let’s look at five essential story ingredients, and then review how to mix them together to make your story so good readers will ask for seconds.

Ingredient #1: Orientation

The beginning of a story must grab the reader’s attention, orient her to the setting, mood and tone of the story, and introduce her to a protagonist she will care about, even worry about, and emotionally invest time and attention into. If readers don’t care about your protagonist, they won’t care about your story, either.

So, what’s the best way to introduce this all-important character? In essence, you want to set reader expectations and reveal a portrait of the main character by giving readers a glimpse of her normal life. If your protagonist is a detective, we want to see him at a crime scene. If you’re writing romance, we want to see normal life for the young woman who’s searching for love. Whatever portrait you draw of your character’s life, keep in mind that it will also serve as a promise to your readers of the transformation that this character will undergo as the story progresses.

For example, if you introduce us to your main character, Frank, the happily married man next door, readers instinctively know that Frank’s idyllic life is about to be turned upside down—most likely by the death of either his spouse or his marriage. Something will soon rock the boat and he will be altered forever. Because when we read about harmony at the start of a story, it’s a promise that discord is about to come. Readers expect this.

Please note that normal life doesn’t mean pain-free life. The story might begin while your protagonist is depressed, hopeless, grieving or trapped in a sinking submarine. Such circumstances could be what’s typical for your character at this moment. When that happens, it’s usually another crisis (whether internal or external) that will serve to kick-start the story. Which brings us to the second ingredient.

[Learn 5 Tools for Building Conflict in Your Novel]

Ingredient #2: Crisis

This crisis that tips your character’s world upside down must, of course, be one that your protagonist cannot immediately solve. It’s an unavoidable, irrevocable challenge that sets the movement of the story into motion.

Typically, your protagonist will have the harmony of both his external world and his internal world upset by the crisis that initiates the story. One of these two imbalances might have happened before the beginning of the story, but usually at least one will occur on the page for your readers to experience with your protagonist, and the interplay of these two dynamics will drive the story forward.

Depending on the genre, the crisis that alters your character’s world might be a call to adventure—a quest that leads to a new land, or a prophecy or revelation that he’s destined for great things. Mythic, fantasy and science-fiction novels often follow this pattern. In crime fiction, the crisis might be a new assignment to a seemingly unsolvable case. In romance, the crisis might be undergoing a divorce or breaking off an engagement.

In each case, though, life is changed and it will never be the same again.

George gets fired. Amber’s son is kidnapped. Larry finds out his cancer is terminal. Whatever it is, the normal life of the character is forever altered, and she is forced to deal with the difficulties that this crisis brings.

There are two primary ways to introduce a crisis into your story. Either begin the story by letting your character have what he desires most and then ripping it away, or by denying him what he desires most and then dangling it in front of him. So, he’ll either lose something vital and spend the story trying to regain it, or he’ll see something desirable and spend the story trying to obtain it.

Say you’ve imagined a character who desires love more than anything else. His deepest fear will be abandonment. You’ll either want to introduce the character by showing him in a satisfying, loving relationship, and then insert a crisis that destroys it, or you’ll want to show the character’s initial longing for a mate, and then dangle a promising relationship just out of his reach so that he can pursue it throughout the story.

Likewise, if your character desires freedom most, then he’ll try to avoid enslavement. So, you might begin by showing that he’s free, and then enslave him, or begin by showing that he’s enslaved, and then thrust him into a freedom-pursuing adventure.

It all has to do with what the main character desires, and what he wishes to avoid.

[Learn important writing lessons from these first-time novelists.]

Ingredient #3: Escalation

There are two types of characters in every story—pebble people and putty people.

If you take a pebble and throw it against a wall, it’ll bounce off the wall unchanged. But if you throw a ball of putty against a wall hard enough, it will change shape.

Always in a story, your main character needs to be a putty person.

When you throw him into the crisis of the story, he is forever changed, and he will take whatever steps he can to try and solve his struggle—that is, to get back to his original shape (life before the crisis).

But he will fail.

Because he’ll always be a different shape at the end of the story than he was at the beginning. If he’s not, readers won’t be satisfied.

Putty people are altered.

Pebble people remain the same. They’re like set pieces. They appear onstage in the story, but they don’t change in essential ways as the story progresses. They’re the same at the ending as they were at the beginning.

And they are not very interesting.

So, exactly what kind of wall are we throwing our putty person against?

First, stop thinking of plot in terms of what happens in your story. Rather, think of it as payoff for the promises you’ve made early in the story. Plot is the journey toward transformation.

As I mentioned earlier, typically two crisis events interweave to form the multilayered stories that today’s readers expect: an external struggle that needs to be overcome, and an internal struggle that needs to be resolved. As your story progresses, then, the consequences of not solving those two struggles need to become more and more intimate, personal and devastating. If you do this, then as the stakes are raised, the two struggles will serve to drive the story forward and deepen reader engagement and interest.

Usually if a reader says she’s bored or that “nothing’s happening in the story,” she doesn’t necessarily mean that events aren’t occurring, but rather that she doesn’t see the protagonist taking natural, logical steps to try and solve his struggle. During the escalation stage of your story, let your character take steps to try and resolve the two crises (internal and external) and get back to the way things were earlier, before his world

was tipped upside down.

[Here's how to turn traumatic experiences into fuel for your writing.]

Ingredient #4: Discovery

At the climax of the story, the protagonist will make a discovery that changes his life.

Typically, this discovery will be made through wit (as the character cleverly pieces together clues from earlier in the story) or grit (as the character shows extraordinary perseverance or tenacity) to overcome the crisis event (or meet the calling) he’s been given.

The internal discovery and the external resolution help reshape our putty person’s life and circumstances forever.

The protagonist’s discovery must come from a choice that she makes, not simply by chance or from a Wise Answer-Giver. While mentors might guide a character toward self-discovery, the decisions and courage that determine the outcome of the story must come

from the protagonist.

In one of the paradoxes of storytelling, the reader wants to predict how the story will end (or how it will get to the end), but he wants to be wrong. So, the resolution of the story will be most satisfying when it ends in a way that is both inevitable and unexpected.

[Understanding Book Contracts: Learn what’s negotiable and what’s not.]

Ingredient #5: Change

Think of a caterpillar entering a cocoon. Once he does so, one of two things will happen: He will either transform into a butterfly, or he will die. But no matter what else happens, he will never climb out of the cocoon as a caterpillar.

So it is with your protagonist.

As you frame your story and develop your character, ask yourself, “What is my caterpillar doing?” Your character will either be transformed into someone more mature, insightful or at peace, or will plunge into death or despair.

Although genre can dictate the direction of this transformation—horror stories will often end with some kind of death (physical, psychological, emotional or spiritual)—most genres are butterfly genres. Most stories end with the protagonist experiencing new life—whether that’s physical renewal, psychological understanding, emotional healing or a spiritual awakening.

This change marks the resolution of the crisis and the culmination of the story.

As a result of facing the struggle and making this new discovery, the character will move to a new normal. The character’s actions or attitude at the story’s end show us how she’s changed from the story’s inception. The putty has become a new shape, and if it’s thrown against the wall again, the reader will understand that a brand-new story is now unfolding. The old way of life has been forever changed by the process of moving through the struggle to the discovery and into a new and different life.

Letting Structure Follow Story

I don’t have any idea how many acts my novels contain.

A great many writing instructors, classes and manuals teach that all stories should have three acts—and, honestly, that doesn’t make much sense to me. After all, in theater, you’ll find successful one-act, two-act, three-act and four-act plays. And most assuredly, they are all stories.

If you’re writing a novel that people won’t read in one sitting (which is presumably every novel), your readers couldn’t care less about how many acts there are—in fact, they probably won’t even be able to keep track of them. What readers really care about is the forward movement of the story as it escalates to its inevitable and unexpected conclusion.

While it’s true that structuring techniques can be helpful tools, unfortunately, formulaic approaches frequently send stories spiraling off in the wrong direction or, just as bad, handcuff the narrative flow. Often the people who advocate funneling your story into a predetermined three-act structure will note that stories have the potential to sag or stall out during the long second act. And whenever I hear that, I think, Then why not shorten it? Or chop it up and include more acts? Why let the story suffer just so you can follow a formula?

I have a feeling that if you asked the people who teach three-act structure if they’d rather have a story that closely follows their format, or one that intimately connects with readers, they would go with the latter. Why? Because I’m guessing that deep down, even they know that in the end, story trumps structure.

Once I was speaking with another writing instructor and he told me that the three acts form the skeleton of a story. I wasn’t sure how to respond to that until I was at an aquarium with my daughter later that week and I saw an octopus. I realized that it got along pretty well without a skeleton. A storyteller’s goal is to give life to a story, not to stick in bones that aren’t necessary for that species of tale.

So, stop thinking of a story as something that happens in three acts, or two acts, or four or seven, or as something that is driven by predetermined elements of plot. Rather, think of your story as an organic whole that reveals a transformation in the life of your character. The number of acts or events should be determined by the movement of the story, not the other way around.

Because story trumps structure.

If you render a portrait of the protagonist’s life in such a way that we can picture his world and also care about what happens to him, we’ll be drawn into the story. If you present us with an emotionally stirring crisis or calling, we’ll get hooked. If you show the stakes rising as the character struggles to solve this crisis, you’ll draw us in more deeply. And if you end the story in a surprising yet logical way that reveals a transformation of the main character’s life, we’ll be satisfied and anxious to read your next story.

The ingredients come together, and the cake tastes good.

Always be ready to avoid formulas, discard acts and break the “rules” for the sake of the story—which is another way of saying: Always be ready to do it for the sake of your readers.

Not sure if your story structure is strong enough to woo an agent? Consider:

Not sure if your story structure is strong enough to woo an agent? Consider:

Story Structure Architect

Become a WD VIP and Save 10%:

Get a 1-year pass to WritersMarket.com, a 1-year subscription to Writer’s Digest magazine and 10% off all WritersDigestShop.com orders! Click here to join.

I picked up Christopher Greyson’s book ‘Girl Jacked’ after seeing the glowing reviews on the Amazon website.

While you could classify it as a mystery thriller, it doesn’t conform to some norms in this genre. As in any mystery novel, you expect your sleuths to engage their wits in uncovering the perpetrator of a heinous crime or murder. That is a given. However, in ‘Girl Jacked,’ this heinous crime/murder is not confirmed till you’ve read about a third of the book. This in no way takes away from the beauty of this story as we get to root for the main protagonists: Jack Stratton and Alice a.k.a Replacement. Officer Jack Stratton has to find the killer of his foster sister, Michelle and clear her good name which is tarnished by the incidents surrounding her death.

Greyson writes in a way that is vivid and puts the reader smack bang in the middle of the action taking place on the page. The dialogue in the book is witty and fast paced. There was a lot of internal monologue in the book that served to add value to the action taking place. I haven’t seen this much use of internal monologue in a while and some people might find it distracting but I got used to it after a few pages.

I found the chemistry between Jack and Replacement was akin to a big brother and his little sister although there were moments when the sexual tension between them was a bit uncomfortable. Replacement is a worthy side-kick and I believe inherits some of the author’s background in the Computer Science world. Don’t expect to delight in guessing ‘whodunit’ as you read this book but rather enjoy the evolving relationship between Jack and Replacement as they discover a world filled with inflated egos, sadistic ambitions and barbaric violence.

I’ll be reading the other books in this series and have a feeling it’s only going to get better and better.

It’s Author Interview Thursday! Woohoo! Are you ready to rumble? Yes? Good. Then let’s get right to it. I came to know our featured author through Sherrill S. Cannon who was on the hot seat a few moons ago. She’s the author of the popular Rachel Racoon and Sammy Skunk series. In the build up to this interview, I discovered that she has a rich knowledge of conservation and a passion for nature. This passion is revealed in all her books and readers of her books will not only be entertained by her stories but will come away with a better understanding of the world around us. I’m so glad she’s chosen to spend some time with us today, so please join me in welcoming Jannifer Powelson.

Yes? Good. Then let’s get right to it. I came to know our featured author through Sherrill S. Cannon who was on the hot seat a few moons ago. She’s the author of the popular Rachel Racoon and Sammy Skunk series. In the build up to this interview, I discovered that she has a rich knowledge of conservation and a passion for nature. This passion is revealed in all her books and readers of her books will not only be entertained by her stories but will come away with a better understanding of the world around us. I’m so glad she’s chosen to spend some time with us today, so please join me in welcoming Jannifer Powelson.

Can you tell us a little bit about yourself and the first time someone complemented you on something you had written? I have enjoyed writing since I was a young girl, though I decided to major in biology in college. However, since I follow the age-old adage and write about what I know, I’ve incorporated much of my biology background into my books. I don’t remember the first time someone complimented me on my writing, but I’ve had several lovely comments about my books. When children tell me Rachel and Sammy books are their favourites, it means the world to me!

What can a reader expect when they pick up a book written by Jannifer Powelson? Whether you read my children’s books or my new mystery novel for adults, you can expect to read and learn about nature.

There seems to be a theme around nature and animals that runs through your books. Can you tell us if this is intentional and where that stems from? I grew up on a farm, where I spent much time working and playing outdoors. My fondness for nature and conservation started early. I majored in biology in college, and I work as a conservationist.

Your most recent book ‘When Nature Calls’ is a departure from your other kidlit books as it’s a full length novel. Can you tell us about some of the challenges you encountered while writing this book?

I really enjoyed writing When Nature Calls. Since it was my first novel, I learned a lot along the way. I had to work on fleshing out some of the characters and making things fairly believable. I self edited this book several times before, during, and after a professional edit. It was much more challenging to edit and proof a novel in comparison to a shorter children’s book.

How do you handle bad reviews?

I have tried to develop a thicker skin. When you write books you put your heart and soul into them. When they are published, you open yourself up to criticism. I know not everyone will enjoy my books; you can’t please everyone. I try to remember that for any negative review, there are plenty of positive reviews to counteract the effects of a bad one.

What have you found to be a successful way to market your books?

Since my children’s books are educational, I use the books as part of educational programs about nature. The books are for sale during these events, and they seem to sell well in conjunction with programs. I target my marketing efforts toward nature centers, state and national parks, museums, and, botanical gardens, as well as many small town businesses that are willing to stock books by local authors.

You own the publishing firm Progressive Rising Phoenix Press with your business partner Amanda Thrasher. Can you tell us how you juggle being a publisher and a writer?

Sometimes it’s hard to find the time for everything. Amanda and I divide up the workload so we can both have time to focus on our books. Progressive Rising Phoenix Press is growing quickly, so there is much work to do. Often times our own books must wait until we have completed work on another author’s book.

What were some of your favourite books as a child?

I loved to read Nancy Drew and Trixie Belden mysteries and also enjoyed reading books by Beverly Cleary and Judy Blume as well.

What three things should writers avoid when writing dialogue?

I’m still learning to write dialogue well. I try not to turn dialogue into monologue. I avoid writing dialogue that is too long or cumbersome. I attempt to get inside the characters’ heads and pretend like they are having a real conversation, so it sounds more natural.

What book or film has the best dialogue that inspires you to be a better writer and why?

There is no one particular book that influences me. I love reading and really enjoy various cozy mystery series. Even though I read for pleasure, I still pay attention to the details that make a great book, such as believable characters and storylines, descriptive settings, and interesting twists and turns. Toy Story or Shrek? Shrek movies have grown on me over the years.

What three things should a first time visitor to Illinois do?

Though Illinois is not normally on everyone’s ideal vacation list, there are several pretty areas to explore. Check out the unglaciated Northwest corner that is hilly and scenic. Southern Illinois contains the Shawnee Forest, and the northern and central portions of Illinois have some beautiful prairie remnants. I try to imagine what it looked like two hundred years ago, before the endless acres of lush prairie were converted to other uses. Of course, you’ll want to check out Chicago and Lake Michigan too.

You grew up on a farm with lots of animals. Can you tell us about an unforgettable experience you had with one of the farm animals?

Though working with livestock is always very interesting, I can’t single out a single event. Many animals have their own unique personalities, just like humans, so observing and experiencing animal behaviour can be entertaining at times. One experience that is very vivid in my mind took place during my wildlife research days as a graduate student. I worked with raccoons but also encountered other animals. One day when letting a skunk loose from a live trap, it became very agitated and sprayed me in the face. Since most of the skunks I accidentally captured were even tempered, this was quite a surprise. Rachel Raccoon and Sammy Skunk characters are derived from my research experiences.

What can we expect from Jannifer Powelson in the next 12 months?

I plan to get busy working on the second book in The Nature Station Mystery Series soon, An Unnatural Selection.

Where can readers and fans connect with you?

Website - www.janniferpowelson.com

Facebook - https://www.facebook.com/pages/Rachel-and-Sammy/112780165400802

Amazon Page - http://www.amazon.com/Jannifer-Powelson/e/B003LNZQF2/ref=ntt_athr_dp_pel_1

Twitter - @JCPowelson

Any advice for authors out there who are either just starting out or getting frustrated with the industry?

Whether you are writing a book or trying to market your work, keep your “to-do” list up to date, and try to tackle a few action items every day. Thanks for being with us today. I have to agree with your last statement because little drops of water do make a mighty ocean. Jannifer made some insightful remarks in this interview and we’d both be delighted to hear your questions or comments. Simply leave your question or comment and remember to share with the social buttons below.

Jannifer Powelson’s Books on Amazon

.

Choosing the right set of words–the diction of your novel–is crucial, especially in the opening pages of your novel. Novels are a context for making choices, and within that context, some words make sense and some don’t.

A novel sets up a certain setting, time period, tone, mood and sensibilities and you must not violate this. If you are writing a gothic romance, the language must reflect this. For thrillers, the fast paced action demands a certain vocabulary. Violating these restrictions means a bump in the reader’s experience that may make them put down the book.

Let’s look at some examples. This is from my book, SAUCY AND BUBBA: A HANSEL AND GRETEL TALE.

Just from the title you know that this is a contemporary retelling of Hansel and Gretel and this sets up expectations for the language that will be used. This is a first look at Krissy, the stepmother.

Just from the title you know that this is a contemporary retelling of Hansel and Gretel and this sets up expectations for the language that will be used. This is a first look at Krissy, the stepmother.

Krissy was singing to herself. Gingerbread days were filled with music, too. Once a month, Krissy made a gingerbread house and took it into town to sell to the bakery for $200. The bakery displayed it in their picture window for a month, and then donated it to a day care. Each month, Krissy checked out a stack of architecture books and pored over them.

Let’s substitute a couple words and see if it bothers you as a reader:

Krissy was caterwauling to herself. Gingerbread days were crammed with music, too. Once a month, Krissy slapped together a gingerbread house and took it into town to peddle to the bakery for $200. The bakery displayed it in their picture window for a month, and then dumped it off at a day care. Each month, Krissy checked out a stack of architecture books and flipped through them.

I’ve been extreme here in word choice, of course. The key is to listen to your story. Where are the places where a single word might interrupt the narrative? Work hard to control your word choices and the overall diction of your story. And I’ll stay with you for the whole book.

.

How do you take an idea to a book? I am just starting the process again and every time, it overwhelms me. I know the process works, but it seems so daunting at this first stage. So, I only look forward to the next task, knowing that taking the first step will lead me onward.

For this story, I’ll approach it on several levels at once:

Outlining. This is the fourth book in an easy-reader series, so I know the general pattern that the book will follow over its ten chapters. Chapter one will introduce the story problem and chapter ten will wrap it up. That leaves eight chapters and each has a specific function in this short format. Chapter 2 introduces the subplot, chapter 4 intensifies it and chapter 6 resolves it. That leaves chapters 1, 3, 5, 7-10 for the wrap-up. Chapters 9 and 10 are the climax scene, split into two, with a cliff hanger at the end of chapter 9. In other words, I can slot actions into the functions of each chapter and make it work. Knowing each chapter’s function makes it easier–but not automatic. I’ll still need to shift things around and make allowances for this individual story.

Character Problem. Making my characters hurt is the second challenge. Squeezing them, making them uncomfortable, making them cry, dishing out grief and mayhem–it’s all part of the author’s job. I tend to be a peace-maker and find this to be quite difficult. But if I can manage to bring my character’s emotions to a breaking point by chapter 8, I’ll be able to move the reader. I’ll be searching for the pressure points for the character as the outline progresses. Hopefully, the emotional resolution in chapter 9-10 will be a twist, something unexpected by the reader.

Back and Forth Between Outline and Characters. The nice thing about focusing on just this much at first is that it is interactive. I’ll go back and forth between plot, character and the structure demanded by this series until the story starts to gel. Will it be easy and automatic? Oh, no. I’ll be pulling out my hair (metaphorically) for a couple days. But by the end of the week (I hope) there will be progress.

How do you start your story? Do you free-write, create a character background, or outline? Which parts interact as you create the basis for a new story?

What Character Are You? Click to Enlarge. Photo Credit: http://www.flickr.com/photos/bk/12392396893/

QUIZ: ARE YOU READY TO WRITE A CHILDREN'S PICTURE BOOK?

- How many pages are in a typical children’s picture book?

- Who is the audience of a children’s picture book? Hint: It's not just kids.

- Are there restrictions on the vocabulary you use in a picture book?

- Do I have to write in rhyme? Do manuscripts written in rhyme sell better?

- Do EPUB books have to the same length as printed books?

Don't start writing that picture book until you know these crucial concepts.

GET THE ANSWERS HERE.

Where should your novel begin? The Harry Potter series doesn’t start with the death of Harry’s parents, because Harry wasn’t old enough to remember that. It doesn’t start with the first day in Hogwarts School because it wouldn’t bring us into Harry’s world with a strong enough sense of character and a strong sympathy for Harry.

Instead, JK Rowling begins the whole series in the Muggle world, with a misfit Harry trying to survive while living under the stairway.

Build Sympathy. One crucial goal of openings is to create sympathy for a character that will carry through many challenges and events. An orphaned child who is forced to live with disagreeable parents will most certainly get sympathy. Poor thing, to be treated so shabbily; it’s not fair. We love our underdogs, don’t we?

Start with the Normal World. For Harry and for the reader, the normal world is the Muggle world where there is no magic. It’s the right place to start, but the wrong place to linger. Readers should understand exactly what the normal situation is before something comes along to shake up the world of the story.

Start with a Day that is Different. Harry’s under-the-stairs world is normal, but it doesn’t stay normal. Immediately something is different. It’s a delicate balance to make sure the contrast is set up between normal and the exciting world introduced in the story. You want enough of the normal to set up the contrast, but too much gets boring. Normal is boring. Think hard about where you might start the story and what are the first small inklings (or big huge inklings, if you choose) of change. Start there or a bit later.

Yes, Darcy! I want to share the story

Yes, Darcy! I want to share the story

of the Oldest Wild Bird in the World

with a special child(ren).

"On Dec. 10, 1956, early in my first visit to Midway, I banded 99 incubating Laysan Albatrosses in the downtown area of Sand Island, Midway. Wisdom (band number 587-51945) is still alive, healthy, and incubating again in December 2011 (and in 2012 and in 2013). While I have grown old and gray and get around only with the use of a cane, Wisdom still looks and acts just the same as on the day I banded her. . .remarkable true story. . . beautifully illustrated in color." -- Chandler S. Robbins, Sc.D., Senior Scientist (Retired), USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Laurel, MD.

CLICK BELOW to view

the story of the 63-year-old bird

in your favorite store.

It’s a time to look backward. What are the 13 most popular posts on Fiction Notes in 2013? Here’s the countdown!

Posts Written in 2013

13. 63 Character Emotions to Explore When your character gets stuck at sad, even sadder and truly sad, explore these options for more variety.

12. 5 Quotes to Plot Your Novel By. We always like to know what other authors think about writing and how they work. These quotes are a tiny insight into the writing process.

11. 5 More Ways to Add Humor. Ever popular, but hard to get right, I always need help being funny.

10. Nonfiction Picture Books: 7 Choices. What types of nonfiction picture books are popular now, especially with the Common Core State Standards.

9. Why Authors Should Believe in Their Websites. This was a response to a posting on Jane Friedman‘s website that challenged why authors need a website at all.

8. Help Me Write a Book. A list of suggested resources that will help you write a book.

7. 7 Reasons Your Manuscript Might Be Rejected. A discussion of the rejection cycle and how to defeat it.

c. Dwight Pattison. My favorite picture that my husband took this year. Pelicans along the Arkansas River

Classic Posts

6. 9 Traits of Sympathetic Characters. How to make that protagonists a nice-guy or nice-girl.

5. 29 Plot Templates. Lost on where to start plotting? Consider one of these options.

4. 30 Days to a Stronger Novel. This series continues to be popular. It’s 30 days of tips for making your novel into the story of your dreams.

3. 30 Days to a Stronger Picture Book. Likewise, 30 days of tips for writing a picture book is hugely popular.

2. Picture Book Standards: 32 Pages. The most frequent question people ask about picture books is how long should they be. Here’s the standard answer, with explanations for why 32 pages is the standard.

1. 12 Ways to Start a Novel. 100 classic opening lines are categorized into twelve ways of opening a novel.

This list reflects the range of topics that consume me and that I want to write about. But it’s not just about me. Please leave a comment with one topic you’d like to see discussed this year.

Yes, Darcy! I want to share the story

Yes, Darcy! I want to share the story

of the Oldest Wild Bird in the World

with a special child(ren).

"On Dec. 10, 1956, early in my first visit to Midway, I banded 99 incubating Laysan Albatrosses in the downtown area of Sand Island, Midway. Wisdom (band number 587-51945) is still alive, healthy, and incubating again in December 2011 (and in 2012 and in 2013). While I have grown old and gray and get around only with the use of a cane, Wisdom still looks and acts just the same as on the day I banded her. . .remarkable true story. . . beautifully illustrated in color." -- Chandler S. Robbins, Sc.D., Senior Scientist (Retired), USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Laurel, MD.

CLICK BELOW to view

the story of the 63-year-old bird

in your favorite store.

An odd thing is happening on my current WIP: I am writing the story out of order.

Here’s the process for this story–which will change, of course, for the next story.

Will I use this process again? I don’t know. Maybe for Book 4 of this series, but maybe not for another genre or other series. Usually, each project needs its own trajectory and working method. All I know is that this is moving me forward. For now.

MIMS HOUSE: Great NonFiction for Common Core

The story of the oldest known wild bird in the world. At 62+, she hatched a new chick in February, 2013. Read her remarkable story. A biography in text and art.

Gifted and Talented

If you have finished a draft of a novel (however messy!), you are Gifted and Talented.

The fact that you are Gifted and Talented has an important implication for revising your story.

GT Learners. First, I’ve talked with Gifted and Talented Teachers about how their students learn. When they learn something new, there’s a stage where they are very uncomfortable. Usually, GTs learn quickly and easily; they catch on. But sometimes the material is more difficult than usual, or more complex, or more puzzling. For some reason, they don’t catch on. They are unsure of what to do next.

GT Learners. First, I’ve talked with Gifted and Talented Teachers about how their students learn. When they learn something new, there’s a stage where they are very uncomfortable. Usually, GTs learn quickly and easily; they catch on. But sometimes the material is more difficult than usual, or more complex, or more puzzling. For some reason, they don’t catch on. They are unsure of what to do next.

At that point, GTs get uncomfortable and since they are rarely uncomfortable with learning, they often bail out. Anger, frustration, fear, impatience–do you experience some of these emotions when you face a revision that just doesn’t seem to be working?

The very fact that writing well is a process of revision is frustrating to a GT. They are used to getting things right the first time around. Maybe the first obstacle is embracing writing as a process.

Once you accept the process, though, you must also accept that facing difficulties in the revision process is normal! But if you’re a GT (and you are!), then it’s doubly frustrating because you so rarely face things that are hard. When I do the Novel Revision retreat, I warn the writers that they may hit a brick wall sometime during the weekend. The process of thinking about revision may start to overwhelm them.

Forewarned is forearmed. I try to head off the problem of frustration by warning that it is inevitable. When revising your story, you will face difficulties. This is normal! Let me say that again: Difficulties are normal. To be expected. Inevitable. A normal part of the process.

You have two choices: face them squarely and deal with them; avoid them and quit. And of course–you can’t quit!

As a GT, you are uniquely qualified to solve difficulties in revising because you do catch on quickly. You know how to locate and use resources that will help. You absorb information from a wide variety of sources. Given a day or so, you could probably tell me 30 ways that others have solved similar problems.

If you have a complete draft of a novel done, you are Gifted and Talented. That’s good news. It might mean you have a lower threshold for frustration, but in the end, it means you’ll make it through the writing process in great shape.

Perseverance or just plain Stubbornness

We’ve heard the stories: Dr. Seuss? first book, To Think I Saw It on Mulberry Street (1937) was rejected twenty-eight times. Neil Simon, in Rewrites: A Memoir tells of over twenty drafts needed for his first play.

We’ve heard the stories: Dr. Seuss? first book, To Think I Saw It on Mulberry Street (1937) was rejected twenty-eight times. Neil Simon, in Rewrites: A Memoir tells of over twenty drafts needed for his first play.

Most of us would have to agree with Vladimir Nabokov, “I have written–often several times–every word I have ever published. My pencils outlast their erasures.”

Or Dorothy Parker, “I can’t write five words but that I change seven.”

Or John Kenneth Galbraith who jokes, “There are days when the result is so bad that no fewer than five revisions are required. In contrast, when I’m greatly inspired, only four revisions are needed.”

Or Truman Capote, “I believe more in the scissors than I do in the pencil.”

We understand that revising means doing it again until it’s right. But psychologically, that means the best trait a writer can have is stubbornness. On days when there is no hope sheer perseverance takes over.

Help

On those days, I highly recommend Art and Fear by David Bayles and Ted Orland. It?s my favorite books on the psychology of making art and goes into much more detail on many more subjects than I can here in five days. There have been days–like when I got that rejection of a novel after two revisions and fourteen months of dealing with an editor–that all I can do is sit at my desk and cry and re-read this book.

And start again.

Perseverance comes in two forms: revising until the story is right and making your art your way over a lifetime. It took Dr. Seuss twenty years after his first book to write The Cat in the Hat. ( 2007 annotated version). It often takes the work of years to hit your stride and produce your best work. We are in this for the long haul and this current book is just one of the waystations. Think career. Get stubborn. Persevere!

How do you deal with those deadly rejections?

MIMS HOUSE: Great NonFiction for Common Core

The story of the oldest known wild bird in the world. At 62+, she hatched a new chick in February, 2013. Read her remarkable story. A biography in text and art.

Happy Holidays

Just got an e-newsletter from the North Pole and Santa passed along these writing tips from the Frosty the Snowman, posted for the young-at-heart who are writing novels this year.

Back by popular demand is my series on writing tips from popular Christmas figures. First published in 2007, they are updated here for your Christmas cheer.

Santa Claus’s Top 5 Writing Tips

12 Days of Christmas Writing Tips (live on 12/3)

The Gingerbread Man’s Top 5 Writing Tips (live on 12/4)

Frosty the Snowman’s Top 6 Writing Tips (live on 12/5)

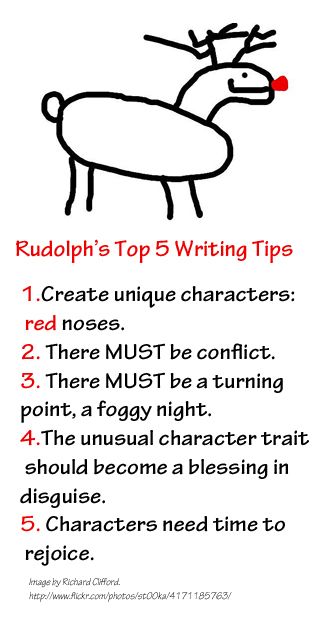

Rudolph The Red Nosed Reindeer’s Top 5 Writing Tips (live on 12/6)

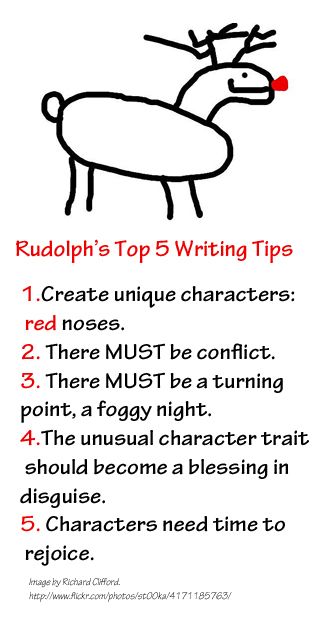

Rudolph the Red Nosed Reindeer’s top 5 Writing Tips

Image by Richard Clifford

- Unique characters. Give characters a tag, a physical or emotional something that makes them stand out from the crowd. That red nose, in the context of a reindeer herd, is absolutely astoundnig.

Rudolph, the red-nosed reindeer

had a very shiny nose.

And if you ever saw him,

you would even say it glows.

- Conflict. The conflict here is the usual playground teasing and bullying of someone who is different. It’s a classic theme because we can all identify with it on some level. Don’t’ be afraid of classic themes; just use them in unique ways.

Also, pile on the conflict. The other reindeer do three things to Rudolph, each an escalation: laugh, call him names, exclude him from games.

All of the other reindeer

used to laugh and call him names.

They never let poor Rudolph

join in any reindeer games.

Poor Rudolph. He must have felt All Alone: “I’m All Alone” from Monty Python’s Spamalot

If you can’t see this video, click here.

- Turning point. After the set up and the conflict, comes the turning point. The crisis here is that Santa must deliver the toys to the children around the world, but the weather isn’t cooperating.

Then one foggy Christmas Eve

- The unusual characteristic becomes a blessing. Again, this is a cliched way of handling a conflict and crisis, but it still works. The very thing that sets the character apart, that makes him/her different and weak, is also the very thing that makes the hero able to save the day. Of course, this means we are matching up conflict and resolution, too. Santa also functions as a sort of mentor here, one who is able to recognize the unique qualities of Rudolph for what they are.

Santa came to say:

“Rudolph with your nose so bright,

won’t you guide my sleigh tonight?”

- Rejoice. It’s not just the climax here, but also the concept of a celebration of successfully completing a quest. Give characters a moment to celebrate. This often comes after a big battle, or a big effort to overcome something.

Then all the reindeer loved him

as they shouted out with glee,

Rudolph the red-nosed reindeer,

you’ll go down in history!

And, of course, you must end with the famous cowboy Gene Autry, singing Rudolph, the Red Nosed Reindeer in 1953. His original recording hit the top of the charts in 1950.

If you can’t see this video, click here.

Think the story is still a little slight for todays’ market? Here’s why.

MIMS HOUSE: Great NonFiction for Common Core

The story of the oldest known wild bird in the world. At 62+, she hatched a new chick in February, 2013. Read her remarkable story. A biography in text and art.

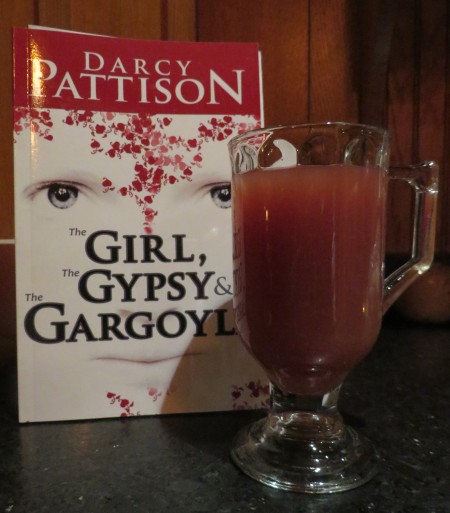

Here’s the cover of my new book that will be out in March 2014! Wahoo! Only 90 days or so till you can read it.

And for your pleasure, here’s the recipe for Cranberry Tea Punch that we always have during the holidays.

Cranberry Tea Punch

1 cup sugar

2 cups Pineapple

4 cups Cranberry Juice Cocktail

4 cups brewed tea (I use Luzianne Decaf)

Cinnamon stix, cloves.

I also like to float slices of lemon and orange.

Warm it up and have it close while you read a book.

MIMS HOUSE: Great NonFiction for Common Core

The story of the oldest known wild bird in the world. At 62+, she hatched a new chick in February, 2013. Read her remarkable story. A biography in text and art.

What do you do when your friends or your editors don’t like your story?

This has indeed happened to me several times, the most recent on a current WIP. One of my reliable first readers has been hesitant to say much about this story and I realized that it’s because she doesn’t like it. The story is a tragedy and while I soften the blow at the end, it does end tragically. READER said that the ending was a “sharp left turn.” But for me, it’s a straight arrow right to the heart of the story.

What to do? Revise to please my reader, or keep it “my way”?

I would be a fool to ignore feedback! Of course, I need to know how others view my stories and where the communication breaks down. I will always revise to make sure I am communicating clearly. What is in my head needs to be clearly reproduced in the reader’s head through the medium of words. That’s communication through writing.

But that’s not the case here. Instead, there’s a gap in vision, or an honest difference in how another person view story and how a story should unfold. READER wanted a happy ending.

There are actually four ways a story can end:

- Happy/Happy. The protagonist gets what s/he wants and that makes him/her happy.

- Happy/Sad. The protagonist gets what s/he wants and that makes him/her sad.