“Graphic novels” for little bitty kids?

Comics for children age four and up?

Not such a preposterous idea. The intuitive narrative form of comics is a whole another kind of reading: Searching panels and pictures along with words for clues to events big and small in the story is an immersion narrative experience. It’s more active than watching video on a screen.

My “great books” education came from Classics Illustrated comics, which I loved. Did they ruin my appetite for dinner?

Heck no, I read plenty of real classics later. My readings of the actual Men Against the Sea, The Dark Frigate, King Solomon’s Mines, Frankenstein, David Copperfield, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde and so many more were only enhanced by my first reading their comic book counterparts.

(In many cases the comics reading was a richer experience than plowing through the actual classic texts. Maybe that says more about me than any literary works. However that’s a story for another post.)

Thank you, Albert Kanter for the great contribution you made to kid culture with the Classic Illustrated series that ran for 30 years beginning in 1941.

On that note, Toon Books, produced by Raw Junior, LLC , endeavors to make comics readers of toddlers and tots.

And who better to tease little ones with artful pictures and graphics into an early habit of reading than, well, another comic book publisher.

Or more precisely a comics publisher/New Yorker magazine art director.

Françoise Mouly is a veteran of more than 800 New Yorker covers, a mom, and the co-founder and co-editor, with her husband cartoonist Art Spiegelman, of the avant garde comics anthology Raw Graphics. That’s where Spiegelman’s family account of the Holocaust, Maus, A Survivor’s Tale, that later won the Pulitzer Prize, first appeared. It was the first comic book to call itself a graphic novel .

Mouly also designed and edited books for Pantheon and Penguin in the late 1980’s and early 1990s. She was helping her first grade son with his reading. she discovered — to her dismay — “beginner reader” texts.

She substituted for their home reading sessions her giant collection of French comic books, and that worked like a charm. It got her thinking, and in 2000 she launched the RAW Junior division to publish “literary comics” for kids of all ages.

She enlisted star writers, artists and cartoonists such as Maurice Sendak, David Sedaris, Jules Feiffer and Gahan Wilson.

In 2008 she started the Toon Books imprint. These were 6″ by 9″ hard cover “comics” that very young children could read on their own.

“Comics have always had a unique ability to draw young readers into a story through the drawings,” Mouly told an interviewer. “Visual narrative helps kids crack the code that allows literacy to flourish, teaching them how to read from left to right, from top to bottom.”

“Comics use a broad range of sophisticated devices for communication,” the Toon Books website quotes Barbara Tversky, professor of Psychology at Stanford University and a Toon Books advisor.

“They are similar to face-to-face interactions, in which meaning is derived not solely from words, but also from gestures, intonation, facial expressions and props,” Tversky says. “Comics are more than just illustrated books, but rather make use of a multi-modal language that blends words, pictures, facial expressions, panel-to-panel progression, color, sound effects and more to engage readers in a compelling narrative.”

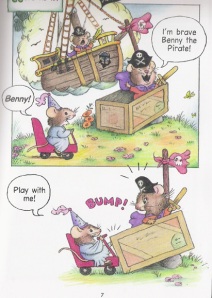

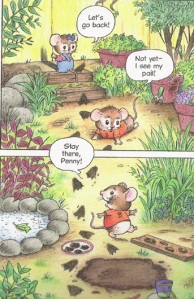

I like the Benny and Penny series by author illustrator Geoffrey Hayes, about sibling mice — a big brother and his little sister and do they ever ring true! In the latest title, The Big No-No, released this Spring, Benny and Penny confront the “new kid” next door.

In Just Pretend, Penny threatens to disrupt Benny’s make believe pirate game (because she needs a hug). But they somehow manage to play together. When Penny momentarily disappears in a game of hide and seek, Benny decides that pretending is better with his sister around than not.

Hayes has written and illustrated about 40 books, including early readers and a Margaret Wise Brown title, When the Wind Blew. The Big No-No and Just Pretend are gently rendered in colored pencil and beautifully orchestrated and paced. The pages are a joy to experience. The little dialogue balloons are so natural and unobtrusive. The books give you the feeling that you’re eavesdropping on the real conversations of real children.

You can read a fascinating interview with Hayes on the Seven Impossible Things Before Breakfast blog.

I haven’t yet seen Stinky about a polka-dotted swamp monster whose turf gets invaded by a little boy. It’s creator is a 25 year old rising comics star Eleanor Davis, a recent graduate of the Savannah College of Art and Design. The American Library Association named Stinky its Theodor Seuss Geisel Honor Book for this year.

I haven’t yet seen Stinky about a polka-dotted swamp monster whose turf gets invaded by a little boy. It’s creator is a 25 year old rising comics star Eleanor Davis, a recent graduate of the Savannah College of Art and Design. The American Library Association named Stinky its Theodor Seuss Geisel Honor Book for this year.

* * * * *

Mark Mitchell hosts “How To Be A Children’s Book Illustrator.” To sample some free lessons from his online course on children’s book illustration, go here.

my father is a retired General, and I often visited him at the pentagon...there were incredible Mauldins in some of the halls, as I remember...good to see this reminder of his witty, important work