A couple of snap polls on Twitter suggest that people pick up comics for many reasons, but here's our own comprehensive poll -- vote often and early!

A couple of snap polls on Twitter suggest that people pick up comics for many reasons, but here's our own comprehensive poll -- vote often and early!

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: writers, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 26 - 50 of 445

Blog: PW -The Beat (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: polls, diversity, Comics, Retailing & Marketing, Writers, artists, chris arrant, Kelly Sue DeConnick, Add a tag

Blog: Robin Brande (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Books, Reading, Fiction, Fantasy Fiction, Fantasy, Fantasy Novels, Writers, Urban Fantasy, Epic Fantasy, Women Writers, Female Warriors, Kristine Kathryn Rusch, P.N. Elrod, Historical Fantasy, Judith Tarr, Laura Anne Gilman, Katharine Eliska Kimbriel, Women Warriors, Leah Cutter, Fiction River, Girl Warrior, Anthea Sharp, Epic Historical Fantasy, Faerie Fiction, Kerrie L. Hughes, Leslie Claire Walker, Story Bundles, Warrior Fantasy, Woman Warrior, Women in Fantasy Story Bundle, Add a tag

It’s cold. In some places, it’s freezing. OF COURSE WE NEED TO READ RIGHT NOW! Bundle ourselves up in fleece and wool and whatever else will do it, and sit for hours totally immersed in story.

Speaking of bundles … do I have a treat for you!

My novel BOOK OF EARTH is currently part of a terrific WOMEN IN FANTASY story bundle, along with nine other books, all guaranteed to transport you away from the cold and wind and snow to places and times … where there might also be cold and wind and snow, but at least there’s also magic and mysticism and other delights that make losing ourselves in fantasy so much fun.

The whole bundle is available for a $15 minimum (although you’re free to pay more, and might want to, since a portion of the proceeds go to The Pearl Foundation, a charity created by singer Janis Ian to promote education by providing scholarships to returning students who have been away from school for a while — a worthy cause!).

But here’s the catch: this bundle will only be available for a limited time. You’ll never find all these wonderful novels grouped together like this for such a low price anywhere else. So the time is now! Winter isn’t just coming, it’s here! Let’s go read our way through it!

Enjoy!

~Robin

Blog: Christine Marie Larsen Sketchbook (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: color, writers, faces, commissioned, SRoB, portraits, people, Add a tag

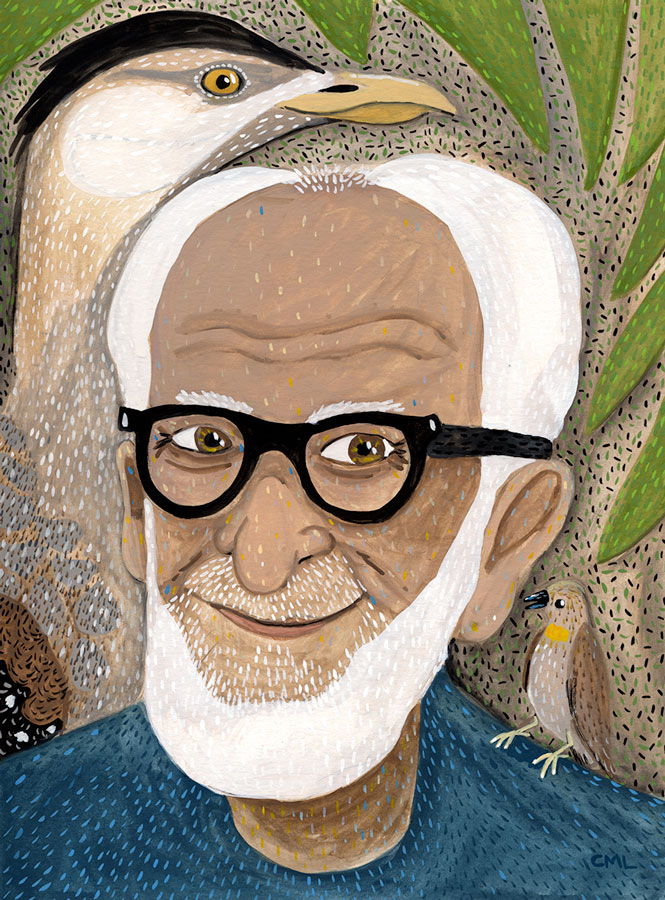

Each week I feature a different author portrait in this Seattle Review of Books column "Portrait Gallery."

Add a CommentBlog: Christine Marie Larsen Sketchbook (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: SRoB, birds, portraits, people, color, writers, faces, commissioned, Add a tag

Blog: Christine Marie Larsen Sketchbook (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: portraits, people, color, writers, faces, commissioned, SRoB, Add a tag

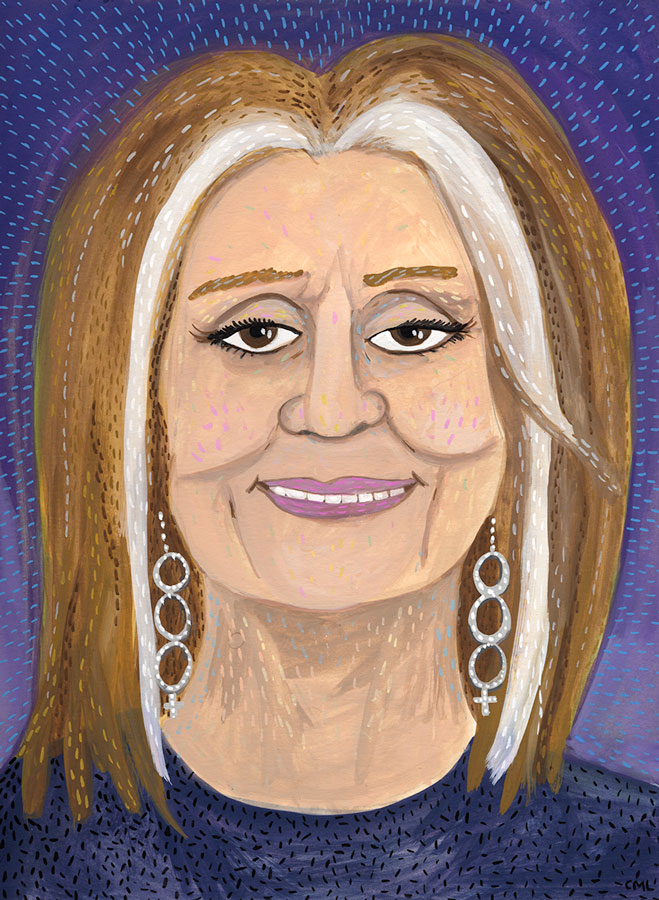

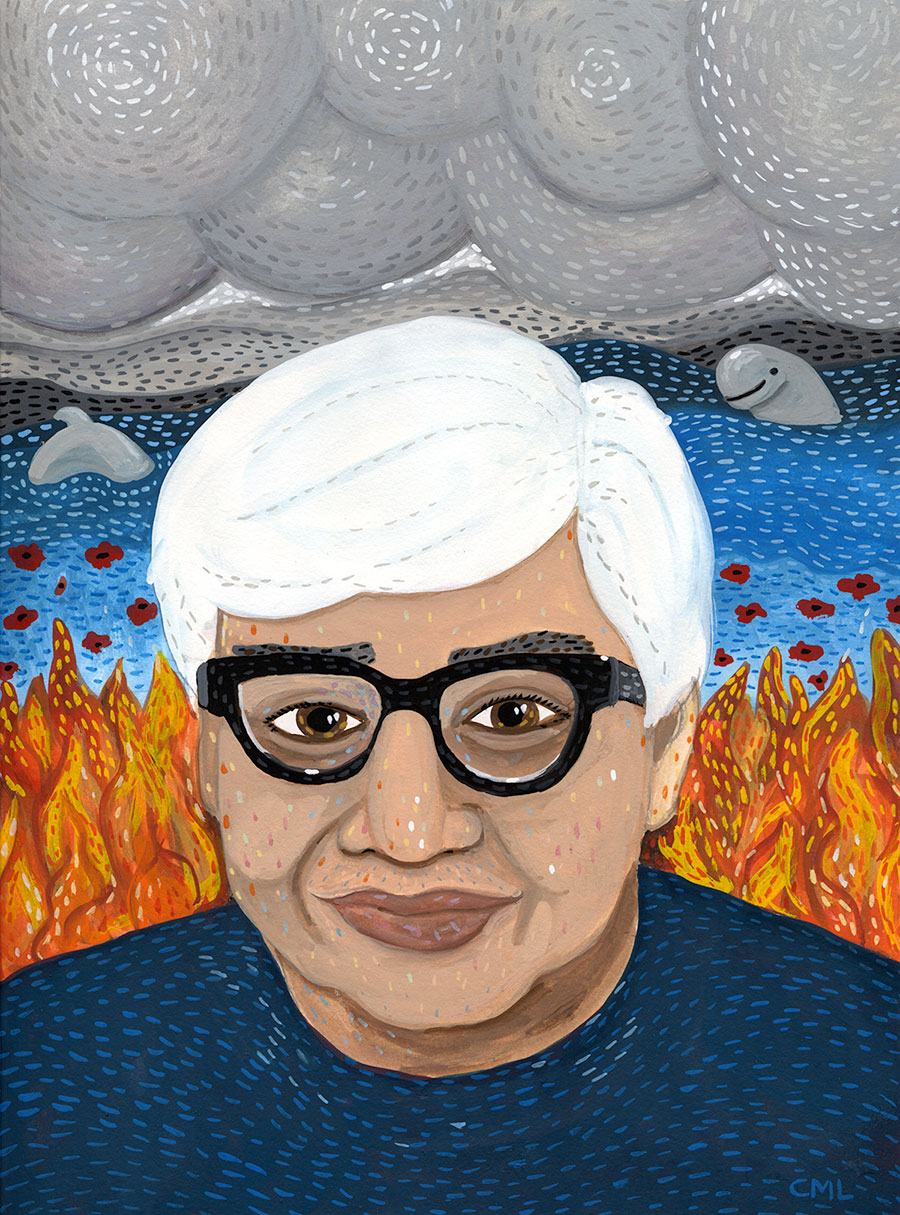

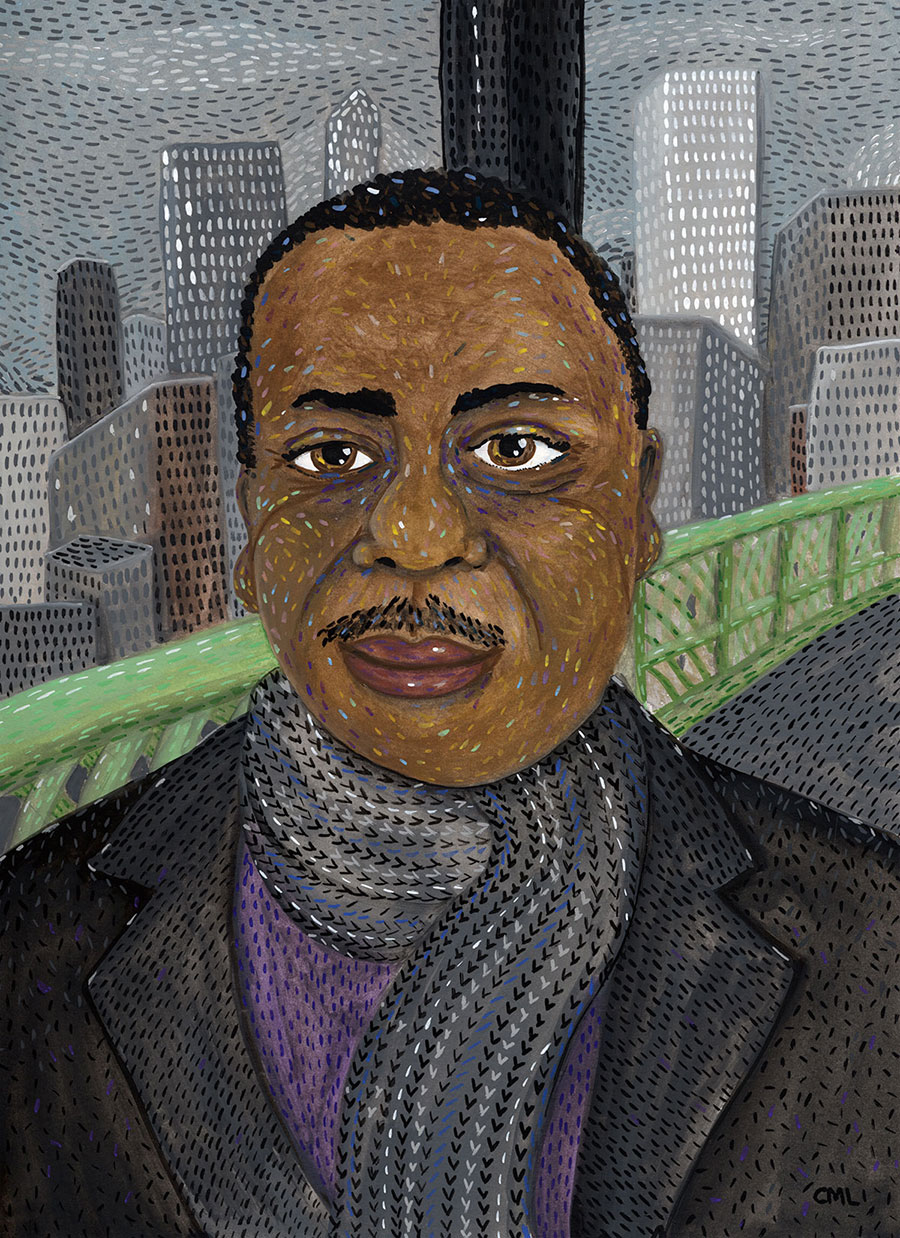

Each week I feature a different author portrait in this new Seattle Review of Books column "Portrait Gallery."

Add a CommentBlog: Christine Marie Larsen Sketchbook (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: SRoB, portraits, people, color, writers, faces, commissioned, Add a tag

Each week I will feature a different author portrait in this new Seattle Review of Books column "Portrait Gallery."

Add a CommentBlog: Christine Marie Larsen Sketchbook (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: SRoB, portraits, people, color, writers, faces, commissioned, Add a tag

Each week I will feature a different author portrait in this new Seattle Review of Books column "Portrait Gallery."

Add a CommentBlog: Christine Marie Larsen Sketchbook (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: SRoB, portraits, people, color, writers, faces, commissioned, Add a tag

Each week I will feature a different author portrait for this Seattle Review of Books column "Portrait Gallery."

Add a CommentBlog: Christine Marie Larsen Sketchbook (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: SRoB, portraits, people, color, writers, faces, commissioned, Add a tag

Each week I will feature a different author portrait in this new Seattle Review of Books column "Portrait Gallery."

Add a CommentBlog: Robin Brande (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Free Writing Tips, November Novel in a Month, Writing Tips, Writing Advice, Writing Life, Writing, Inspiration, Writers, NaNoWriMo, Free Stuff, How To, Writers Advice, Add a tag

The response has been great! We’ve assembled a nice group of folks who are looking forward to their free daily writing tips all through the month of November.

There’s still time to sign up. Just go here for all the details and to get the free download of TOP 10 MISTAKES WRITERS MAKE. And be sure to tell your other writing pals. The more the merrier!

Blog: The Mumpsimus (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Writers, novels, queer, William Plomer, Add a tag

I mentioned William Plomer in passing when discussing my summer research on Virginia Woolf. Thanks to the wonders of Interlibrary Loan, I was recently able to read his fourth, and perhaps least-read (which is saying something!) novel, The Invaders. It's an odd book, one that sometimes feels a bit under-cooked, with an ending that seems to me perfunctory, forced, and utterly unsatisfying. Yet there are also moments of real artistry and interest, and I've found myself thinking about it continuously since I finished it a week ago.

The Invaders is, among other things, a gay novel, but it doesn't get noted in even some of the most comprehensive studies of gay fiction, and Plomer deserves to be generally better known by scholars of queer literatures. He was not as talented or accomplished a fiction writer as many of his friends in the London literary scene, but his point of view was unique among them, because though he was mostly educated in England, his home until he was in his 20s was South Africa, and then he moved to Japan for a few years, before finally settling in London (though with many excursions elsewhere, particularly Greece). After The Invaders, he wrote only one more novel (and that 18 years later), but he published numerous volumes of poetry, biography, autobiography, etc. Fiction seemed to defeat him eventually. It's unfortunate, because there's a lot in The Invaders to suggest that if he had let down his guard a bit, if he had trusted the characters and stories more, if he had not been so seduced by English propriety, he might have been able to rekindle the creative fury that propelled him originally.

|

| Plomer, 1933. Photo by Humphrey Spender |

Plomer's first novel, Turbott Wolfe, written in his late teens, remains the most famous of his books today, and was championed by Nadine Gordimer. There's a brash energy to it that disappears from a lot of his later fiction, and it's more aesthetically daring than what he wrote subsequently. Sado, his next novel, tells the story of Europeans in Japan. It's more subdued and oblique than Turbott Wolfe, but also more openly about homosexual desire, though "openly" here is a relative term, as all the homosexual desire, though not difficult to see, is implied. Plomer's next novel, The Case Is Altered, is a sort of novel of manners that becomes a tale of murder (as, I would submit, all novels of manners ought). It was a significant success, helping to keep the Hogarth Press afloat during the 1930s. In Leonard and Virginia Woolf as Publishers, J.H. Willis, Jr. describes the novel succinctly, noting first that it was based on a gruesome murder in Plomer's own boarding house:

Although the crazed butchery of Beryl Fernandez by her husband in front of their small child is the shocking climax of the novel, it does not constitute the main interest in the book. Plomer's first English novel explores in depth the traditional subject of a respectable rooming house on its way down, but the most intense aspect of the novel is the thinly disguised homosexual relationship that develops between the Plomer-like hero, Eric Alston, and Willie Pascal [note the initials], the extroverted, working-class brother of Alston's girlfriend Amy. It was Plomer's most overt statement of his sexual identity in fiction and went beyond the lyrical eroticism of Sado. (203-204)By the time The Case Is Altered became a success in 1931, Plomer was well established in England's literary circles. At the end of the '20s, he'd become friends not only with the gay male writers of his own generation (e.g. W.H. Auden, John Lehmann, Stephen Spender, and Christopher Isherwood), but also with E.M. Forster, who remained a close, lifelong friend.

And then in 1933 Plomer changed publishers, moving with a short story collection, The Child of Queen Victoria, from the Hogarth Press to the more mainstream Jonathan Cape (with whom he would soon become an employee, leading to his role in Cape's acquisition of his friend Ian Fleming's James Bond novels). The next year, Cape released The Invaders, a story of a middle-class London family's relations with a variety of mostly working-class people. (I will summarize and quote from a lot of the book as I go on, given how rare it is.)

The novel doesn't really have a plot, just encounters, and yet there's a momentum and tension to it all, because it always feels that one of these encounters could go horribly wrong at any moment. That tension is mostly false. Characters do encounter disappointments, misunderstandings, frustrations, anger, and, in the end, get involved with a robbery ... but the consequences for the middle-class family that we are set to identify with are almost nil, and even most of the working-class characters end up pretty well, if occasionally bruised and disillusioned.

The "invaders" of the title are the working-class characters, and one of the ways the novel is interesting is in its portrayals of class difference. The main character is Nigel Edge, a veteran of World War I (and badly injured in the war), who works at a tea importer/distributor and lives with his cousin, Frances, and her father, Uncle Maurice, who had been a colonel in the Boer War. Uncle Maurice has strong ideas about class differences and considers anyone from the working classes to be congenitally dishonest. Class differences seem to him eminently reasonable and necessary. Nigel and Frances are no revolutionaries, but their faith in the class system is not especially strong, and Nigel especially is drawn to the working classes. In some ways, this is clearly because by spending his time among people of a lower class, he's able to feel better about himself: compared to theirs, his life is comfortable, prosperous, and well-ordered. But his life is neither interesting nor attractive, and he is a failure as a conventional man: he lives with his cousin and uncle rather than a wife, he has no children, and though he fought and was wounded in the war, his tastes and mannerisms are far from virile.

Interestingly, the novel does not begin with Nigel's point of view. The first chapter is a lovely, panoramic description of London that seeks to establish the variety of people and sites, the numerous possibilities of interclass contact, particularly around the Marble Arch. Here's the first paragraph:

Gleaming and stinking, gliding and vibrating, the traffic swerves and jostles round that squat anachronism, the Marble Arch. This was Tyburn. Butchery, cries of agony, steaming entrails, calm courage, Perkin Warbeck and Claude Duval, have helped to prepare the scene. Go this way, there is a nunnery; go that way, there is a public house; go down there, and you will come to rich people's houses. You aren't a nun, you don't drink and will never be rich, so for you there is a large hotel, a large cinema, and behind those hollow cliffs some sort of comfort and amusement may be bought. And over there, beyond the wheels and windows of the traffic, is the grass and the comparatively open air, the common heritage of all of us corpuscles who are carried from time to time through this artery of the great body of London, or held there for a while with the policeman on point-duty, the beggar who scratches himself at the gate, or the commissionaire in gold braid at the foot of the cliff. Here is somebody with a grudge, here is somebody whistling, the old lady is about to light a cigarette, the young woman wears jodhpurs and a monocle, and a pavement artist is arguing with his brother-in-law over the merits of a greyhound.This goes on for a few pages, until the chapter ends with: "Something must be wrong, but something has been and will always be wrong, with the faces round the Arch." The next chapter introduces us to Tony Hart, recently arrived in London from Lancashire. He is starving on the streets, but he rejects charity. He feels watched, judged. One day, he helps a stranger who has fallen on the steps of a tube station. This is Nigel. Tony trusts Nigel for some reason, lets him buy him some food, and Nigel offers to try to find some work for him at Uncle Maurice's house. Soon, we slip into Nigel's point of view, and see him at home with his uncle and cousin. Nigel yearns for a bit of subversion:

"I read in the paper this morning," said Nigel, "that there's an international group which does nothing but smuggle people into countries that won't allow them to come in straightforwardly. They fake passports, provide disguises, teach the elements of conversation in various languages, bribe the captains of coasting steamers, and so on. Of course they do it for profit, but I wouldn't mind doing it for pleasure."Tony comes to clean the windows of the house and meets the new maid, Mavis, herself only recently arrived in the city (seeking to escape a boring rural life, to make her fortune, etc.), and soon enough they fall in love. Eventually, Mavis's brother, Chick, stops by, as he's in the military and based in London. He and Nigel pass each other on the steps, and Nigel is immediately taken with him, even more than he was with Tony. They visit with each other a lot, have long conversations, stare deeply into each other's eyes. (Chick was based on one of Plomer's lovers, a trooper with the Royal Horse Guards.) Tony remains as steadfast and decent as ever, but Mavis is greedy and ambitious, and ends up involved with Tony's felonious brother, Len, an involvement that concludes with a robbery, with Len going back to prison and Mavis realizing the errors of her ways and returning home, where she seems to belong. Nigel's affair with Chick falls apart when Nigel feels that Chick has not entirely honest and has not been paying enough attention to him — Nigel seems to suspect that Chick might prefer being with a woman. (Poor, not-so-bright Chick seems rather blindsided by Nigel's jealousy and his curt dismissal of him.) Nigel goes on holiday to the south of France. He disappears one night, and his proper, married, middle-class friend, Robin, traces him to a seedy bar:

"Why?"

"Oh, simply as a protest against the way the modern world is arranged."

"So you're becoming an anarchist?"

"It looks rather like it, doesn't it?"

"He's only teasing you, father," said Frances. "Don't take any notice of him."

"I'm worried to see him getting more subversive," said the Colonel, speaking of NIgel as if he was not present, "instead of taking things as they are and making the best of them." (33)

The dancing was going on behind a second bead curtain at the end of the room. Together with the stridency of the gramophone could be heard the sibilant steps of the dancers. Robin strolled over to have a look. There were four couples dancing. Two women were dancing together, and so were two men. One of them was Nigel, the other a working man in a blue shirt. Nigel was so engrossed in the dance that he did not notice Robin for a moment or two.Then follows a long paragraph from Robin's point of view — he finds the atmosphere in the place "oppressive and uncomfortable", and the various elements and people combine to "produce a distasteful, an almost horrible effect on him. There was an air of rhythm and ritual, of acceptance and celebration, that made him long to escape" (275-276). Nigel is perfectly happy, and was thinking of spending the night, but decides that he'll go back with Robin and set Yvonne's imagination at rest. The chapter ends:

"Hullo, Robin," he said suddenly.

Robin felt a little uncomfortable.

"I hope I don't intrude?" he said.

"Well, I wasn't expecting you," said Nigel with a smile, "but it's very nice to see you. We'll have a drink."

He came out with his partner, and all three sat at Robin's table. The partner had an amiable face, Robin thought, but rather beady black eyes.

"I came along," he said, "because Yvonne was worried about you. She made me come. I don't think she trusts you to look after yourself."

"What a sweat for you," said Nigel. "I am sorry for dragging you out."

"It's all right. Glad to see you enjoying yourself." (274-275)

"Phew!" said Robin. "It was stuffy in there."This, in many ways, is the climax of the novel. After it, there's fewer than 30 pages left, and they're mostly devoted to tying up loose ends. Nigel returns to London and his job, and he thinks for a moment that he should perhaps marry Frances. (Plomer himself had recently been wondering if he should get married.) He decides not, as their friendship might be ruined, and he clearly isn't really interested in her in the way a husband should be. He wonders if his desire for marriage is a result of the "emancipation of women" and a feeling of the loss of male power and privilege. The thought is not concluded. The brief final scene of the novel begins: "The invaders had gone" (304). Tony shows up at Nigel's apartment (mid-way through the novel, he decided to move out of his uncle's house) to see if the windows need washing. They chat, then the novel ends with Nigel making a proposal:

"I like that place," said Nigel.

"Well, I'll tell you what I'm going to do. I'm going to lend you your fare home. I think it's time you had a holiday. Mind you, I said 'lend', not 'give'. You can pay me back when your ship comes in."It's a strange ending — one in which people return to where they "belong", and in which Nigel has gained a mysterious sense of peace. What is the "phase" of life that has ended? His attraction to working class men? He feels as if he knows where he is ... but where is that? London, his apartment, the modern age? He is no longer possessed with the subversive/anarchistic desire to help immigrants get to London, but instead with the (conservative) desire to help people go home. He is full of hope, but it can't be the hope of a heteronormalized life, because he's rejected that. Somehow, in rejecting Chick, in dancing in a gay bar in Nice, in sending Tony home, he has found the balance and meaning of his life. He is no longer invaded.

Tony's face grew brilliant with pleasure.

As for Nigel, it was a long time since he had felt the wound in his head. He felt calm and resigned, and hopeful about the future. He did not know why he was hopeful, but he felt that a phase of his life was ended. He felt as if he knew where he was. (304).

When The Invaders was published in 1934, Plomer's friends and some of the reviewers tended to refer to its presentation of sexuality as "ambiguous". This is true to some extent, but it would be difficult to argue that Nigel is not a gay man — he is clearly attracted to Tony and infatuated (for a time) with Chick, he goes to the bar in Nice, he's threatened with blackmail (by a lackey of Tony's brother Len). He never quite identifies himself as a homosexual, an invert, a man of the "Oscar Wilde type", etc., nor the does the text ever say that he wants to have sex with the men he is drawn to, but it's not hidden. Where Plomer's narrative reticence in Sado can seem coy, even annoying, in The Invaders it seems to me a useful technique for showing these characters and their world — some of the scenes with Chick are charming, the scene in Nice is marvelous (mostly because of just how comfortable Nigel is there, and how uncomfortable Robin grows), but there is ambiguity, and it's the ambiguity we see in that ending, an ambiguity that seems to defeat a lot of what's going on in the rest of the book (unless we read it ironically, which is certainly possible — after all, the first paragraph of the novel established "you" [which may be us, the readers] as Tony. And indeed, with the story ending, we are being sent home). The chaotic threat of homo-pleasure is defeated and order is restored, with everyone going back to where they belong.

Plomer's quiet approach to writing about gay characters was not in step with the times, as his biographer Peter Alexander noted:

...writers such as Rosamond Lehmann had dealt explicitly with homosexuality, and Plomer's publishers actually encouraged him to be more open about the matter in The Invaders, Rupert Hart-Davis [director of the Jonathan Cape publishing company] writing that the one criticism he had of the manuscript was that Plomer had been vague about the scope of Nigel's relationship with Chick: "You don't say, and hardly even infer, whether they went to bed together or not." But Plomer declined to expand the passage. (194)The overlaps of class and sex in The Invaders are ones that will be familiar to anyone who has read E.M. Forster's Maurice. It's possible, in fact, that Plomer himself had read it when he wrote The Invaders — Forster tended to share the manuscript with gay friends (sometimes as a test of their friendship); Isherwood read it in 1933, and Plomer introduced Isherwood to Forster. (Naming Nigel's conversative old uncle "Maurice" might have been a little in-joke.) But Plomer certainly wouldn't have had to read Maurice to decide on the theme of inter-class relationships, for during this particular era of English gay male history, such relationships were the most common ones upper-class gay men would have, as Alexander notes:

One of the curious features of English homosexuals of the upper class at this period was that as a rule (though with notable exceptions) they did not regard each other as potential lovers. Spender was to remark years later, "It would have been almost impossible between two Englishmen of our class ... Men of the same class just didn't; it would have been impossible, or at least very unlikely." This behavior may have originated in the English public schools in which so many of them had been educated, where a senior boy often chose a younger boy as a "friend", and tended to avoid his equals in the school hierarchy.Plomer wasn't politically committed in the way his friends were, but he detested the English laws regarding homosexual conduct, and he seems to have shared at least some of Nigel's occasionally subversive inclinations. From the time of Turbott Wolfe, he'd seen sex as a solution to political problems, and it's certainly possible that he thought homosex was a path toward dismantling the class system. But he was no class warrior (even if he was more active, in every sense, than Nigel).

Certainly Plomer had always been attracted to his social inferiors, if only because this gave him control over the relationship. ... With the younger writers, Spender, Auden, and Isherwood, the impulse to choose working-class partners was reinforced by left-wing political views. (180)

One of the reasons that The Invaders may have disappeared from even the most inclusive of gay canons is that it was a bit old-fashioned even for its own time. Where writers like Isherwood and Spender delighted in pushing the edges of what was acceptable, Plomer was far more comfortable in a more liminal space.

In a letter to Plomer dated 26 September 1934, E.M. Forster expressed a criticism of The Invaders:

What seems to [be] not satisfactory in the book is a thing which I find wrong in A Passage to India. I tried to show that India is an unexplainable muddle by introducing an unexplained muddle — Miss Quested's experience in the cave. When asked what happened there, I don't know. And you,Forster is insightful here. (More insightful regarding Plomer, I think, than about his own novel.) The Invaders fails to be a great novel at least partly because Plomer couldn't let Nigel become ... something. In the end, his sense of peace rings false because it is so random and so against all the facts the book presented up to that point. If the novel had ended with Nigel and Robin walking out of the bar in Nice — if the last line had been, "'I like that place,' said Nigel", it would have been far more effective, even though lots of loose ends would have still been left untied. But Plomer's instincts (and, perhaps, fears) led him to squeeze Nigel into a form that does not follow from the rest of the book, that makes no sense — that, and not so much Nigel's homosexuality, is the muddle. It's not so serious a fallacy for Forster's work because A Passage to India is actually strengthened by the ability of readers to make their own sense of Miss Quested, but it is a failure for Plomer's novel because while we have enough information to make sense of him as a gay man who genuinely likes (and is also sexually attracted to) working class men, we cannot make sense of him as he is in the final scene. Nor, I suspect, could Plomer.hopingexpecting to show the untidiness of London, have left your book untidy. —Some fallacy, not a serious one, has seduced us both, some confusion between the dish and the dinner.

I'm all for these London books of yours. They seem to me about a real town.

The Invaders was Plomer's last novel until his final one, Museum Pieces, was released in 1952. I haven't read it, but Alexander praises it as Plomer's most accomplished fiction, and also says, intriguingly:

In essence it is the story of [Plomer's friend] Tony Butts's life, told by a young female narrator. What Plomer had done in Turbott Wolfe, in making it possible for his hero to fall in love with another man by slipping the loved one into a dress, he did at much greater length, and with greater success, in Museum Pieces. (266-267)While it may be true that Plomer was most comfortable, and most successful, when writing about men from a female perspective, it would be a shame for the world to completely forget his efforts in Sado, The Case Is Altered, and The Invaders to write, however quietly, however reticently, about gay desire.

"I like that place," said Nigel.

Blog: Robin Brande (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Writing Tips, Writing Advice, Writing Life, Writing, Inspiration, Writers, NaNoWriMo, Free Stuff, Writing Inspiration, How To, Writing Motivation, Free Writing Advice, Add a tag

November is novel writing month! I’ve decided to expand the secret gift I was going to send a writer friend of mine, and send out daily writing inspiration and tips to anyone else who would like them! Here are the details. Sign up and let’s write!

Blog: The Mumpsimus (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: books, Publishing, Writers, Faulkner, Woolf, literary history, Thomas Ligotti, Add a tag

When interviewed by a reporter from the Wall Street Journal regarding Thomas Ligotti, Jeff VanderMeer was asked: "Can Ligotti’s work find a broader audience, such as with people who tend to read more pop horror such as Stephen King?" His response was, it seems to me, accurate:

Ligotti tells a damn fine tale and a creepy one at that. You can find traditional chills to enjoy in his work or you can find more esoteric delights. I think his mastery of a sense of unease in the modern world, a sense of things not being quite what they’re portrayed to be, isn’t just relevant to our times but also very relatable. But he’s one of those writers who finds a broader audience because he changes your brain when you read him—like Roberto Bolano. I’d put him in that camp too—the Bolano of 2666. That’s a rare feat these days.This reminded me of a few moments from past conversations I've had about the difficulty of modernist texts and their ability to find audiences. I have often fallen into the assumption that difficulty precludes any sort of popularity, and that popularity signals shallowness of writing, even though I know numerous examples that disprove this assumption.

When I was an undergraduate at NYU, I took a truly life-changing seminar on Faulkner and Hemingway with the late Ilse Dusoir Lind, a great Faulknerian. Faulkner was a revelation for me, total love at first sight, and I plunged in with gusto. Dr. Lind thought I was amusing, and we talked a lot and corresponded a bit later, and she wrote me a recommendation letter when I was applying to full-time jobs for the first time. (I really need to write something about her. She was a marvel.) Anyway, we got to talking once about the difficulty of Faulkner's best work, and she said that she had recently (this would be 1995 or so) had a conversation with somebody high up at Random House who said that Faulkner was their most consistent seller, and their bestselling writer across the years. I don't know if this is true or not, or if I remember the details accurately, or if Dr. Lind heard the details accurately, but I can believe it, especially given how common Faulkner's work is in schools.

And this was ten years before the Oprah Book Club's "Summer of Faulkner". I love something Meghan O'Rourke wrote in her chronicle of trying to read Faulkner with Oprah:

Going online in search of help, I worried about what I might find. What if no one liked Faulkner, or—worse—the message boards were full of politically correct protests of his attitude toward women, or rife with therapeutic platitudes inspired by the incest and suicide that underpin the book? But on the boards, which I found after clicking past a headline about transvestites who break up families, I discovered scores of thoughtful posts that were bracingly enthusiastic about Faulkner. Even the grumpy readers—and there were some, of course—seemed to want to discover what everyone else was excited about. What I liked best was that people were busy addressing something no one talks about much these days: the actual experience of reading, the nuts and bolts of it.We often underestimate the common reader.

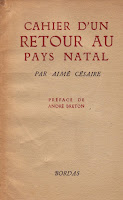

Which brings me to another anecdote. When I was doing my master's degree, I fell in love with the poetry of Aimé Césaire, particularly the Notebook of a Return to the Native Land. I was at Dartmouth, so our instructor (who later very kindly joined my thesis committee) was an expert on Césaire and had spent time in Martinique with him. I asked him how it was possible for someone who wrote such complex, thorny stuff to have become so popular among not just individuals, but whole groups of people who had not had great access to education and who may have little knowledge of modernist poetry. He said something to the effect of: Difficulty depends on what you expect, and what your context for understanding is. If your experience and perception of the world fits with that of the writer, then the form a great writer finds to express that experience and perception is going to be accessible to you, or at least accessible enough to allow you some level of basic appreciation from which to build greater appreciation. He said he'd seen illiterate people deeply, deeply moved by Césaire's poetry when it was read aloud. He knew countless people who had memorized whole passages. He himself fell in love with Césaire's work when he was at school in England, far away from home, and his roommate, who was from the Caribbean, had written (from memory) passages of the Notebook on the ceiling of their dorm room so that it would be the last thing he saw each night and the first thing he saw each morning. Césaire may not have been an international bestseller, but his popularity is real, and is a kind any writer would be humbled by and grateful for.

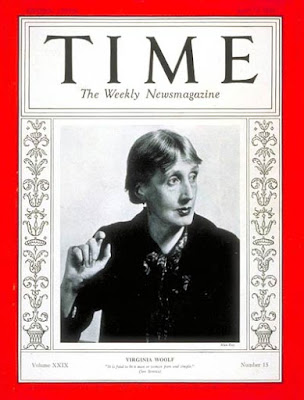

I've been reading around in Modernism, Middlebrow, and the Literary Canon: The Modern Library Series 1917-1955 by Lise Jaillant, which includes a fascinating chapter on Virginia Woolf. While the information about how Orlando sold well from the beginning is familiar to anyone who's read much biographical material about Woolf, far more interesting and revealing is the discussion of the fate of Mrs. Dalloway in the Modern Library edition in the US. This actually has a lot of parallel to Ligotti becoming part of the Penguin Classics line, for, as Jaillant writes, "The Modern Library was the first publisher's series to market Woolf as a classic writer.") During and immediately after World War II, the Modern Library edition of Mrs. Dalloway sold quite well, at least in part because of its use in schools:

In 1941-42, Mrs. Dalloway sold four copies to every three of To the Lighthouse. This trend continued after the war, a period characterized by a huge rise in student enrolments, and an increasing number of courses on twentieth-century literature. The Modern Library edition of Mrs. Dalloway was often adopted for use in survey courses at large universities. In 1947, for example, one professor at the University of Wisconsin ordered 1,400 copies of Mrs. Dalloway, and another one at the University of Chicago ordered 800 copies of the same book. In the 1940s, Mrs. Dalloway sold around 2,800 copies a year. If we look at the twenty-year period from 1928 to 1948, Mrs. Dalloway sold 61,000 copies.It probably would have gone on like that if the Modern Library hadn't lost the reprint rights to Mrs. Dalloway — Harcourt/Brace had decided to start their own line of inexpensive "classic" editions (Harbrace Modern Classics). Attitudes toward modernist novels had changed, too, as Jaillant says: "...the idea that a modernist work could also be a bestseller was increasingly contested in the 1940s and 1950s, at the time when modernism was institutionalized in English departments. The popularity of Mrs. Dalloway and To the Lighthouse was soon forgotten, as modernism came to be seen as a difficult movement for an elite" (102). (I don't know how well Mrs. Dalloway and To the Lighthouse sold between 1948 and the 1970s. By 1975 or so, Woolf was championed by feminist scholars and started on her way to becoming one of the most frequently studied writers on Earth. I've been told that sales of her books were pretty dismal by the end of the 1960s, and that most of her books were out of print, but that may be more a matter of memory and perception than fact. This is something I need to look into further.)

Mrs. Dalloway and To the Lighthouse are not easy books. They aren't The Waves, but they're still nothing anyone would ever describe as "easy reads". (The Waves did very well at first, since it was Woolf's first novel after Orlando, selling just over 10,000 copies in the first six months in the UK, but it then dwindled to only a few hundred copies sold in the UK in the next six months, according to J.H. Willis) The various editions of Mrs. Dalloway and To the Lighthouse still sell well today, and are not only beloved by English professors, but by all sorts of common readers who come upon them in a class or just in the course of ordinary life and find something in the pages worth wrestling with. Even The Waves is deeply loved by many people, and it's one of the most difficult of modernist texts. But it, like all of Woolf's best writing, does things to you few, if any, other books do.

This gets back to what Jeff said about Ligotti: "he’s one of those writers who finds a broader audience because he changes your brain when you read him." If readers trust that the effort of learning to read a strange or difficult writer is worth it, then they may put forth that effort. Brains are stubborn, and sometimes resist being changed. I threw Faulkner's Absalom, Absalom! across the room three times when I first read it. Eventually, I put in enough work that the book was able to teach me how to read it. And then we were in love, eternal love.

There's no sure pathway to such things, for writer or reader, and of course there are plenty of marvelous, difficult writers whose work has never succeeded much, if at all. In many cases, success (eventual or immediate) is a matter of packaging, and sometimes that packaging is deceptive. Look at Faulkner, for instance. His reputation among critics and scholars in the 1930s was generally high, but the only book that sold well was his sensationalist pulp novel Sanctuary. The Southern Agrarians (and, later, New Critics) rather oddly reconfigured and tamed Faulkner, downplaying and flat-out misinterpreting and misrepresenting the darkness, ambiguity, and weirdness of his work. The biggest successes at this were Malcolm Cowley, who gave up left-wing politics around the time he started editing the various Viking Portable editions of major writers, and Cleanth Brooks, who palled around with the Agrarians and helped create and promulgate New Criticism. Cowley's Portable Faulkner presented a simplified and superficial vision of Faulkner, while Brooks's studies of Faulkner provided (mis)interpretations of his works that made Faulkner seem like an unthreatening nostalgist, a writer palatable both to the more conservative of Southern critics and the blandly liberal Northern critics. The simplified/sanitized/superficial view of Faulkner led to a Nobel Prize and quick canonization. Faulkner himself even seems to have bought into the new, cuddly presentation — his last great work was Go Down, Moses in 1942, with nothing written after it of comparable quality, depth, or strangeness. Some of the later books and stories are quite readable, but they're relatively shallow and often cloying. Partly, or perhaps even fundamentally, this was the result of chronic alcoholism catching up to Faulkner, but it was also a matter of his having apparently decided to write what his growing audience expected of him.

Still, even with all its simplicities and superficialities, the canonization of Faulkner allowed his work to stay in print, to receive wide distribution, and to be read. Many people probably didn't read past the Agrarian/New Critic view for decades, but I expect many others did. (Especially people influenced by existentialism, who would have seen the darkness and even nihilism within the best writings. For a long time, and maybe still, people outside the US academy saw a deeper, stranger Faulkner than US professors and critics.) The books were available, the words could be read.

The lesson here, if there is a lesson, is that literary history is complex and doesn't easily boil down to simple oppositions like popular vs. difficult. And that so much depends upon how a book is sold to readers, and how readers have the opportunity to discover a book, and what they expect from it and hope from it, because what they hope and expect from a book will determine how they find their way into it, and it will further determine whether they stick with it when the way in proves challenging. If writers, publishers, critics, and teachers respect readers as intelligent beings and keep high expectations for them, some great things can happen sometimes, especially if a "difficult" book is able to stay in print for a little while, to lurk on shelves until it is discovered by the readers who need it, the readers ready to help its words live.

Blog: OUPblog (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: J.R.R. Tolkien, Books, History, Literature, Poet, Biography, Oxford, C.S. Lewis, writers, T.S. Eliot, oup, British, magician, W.H. Auden, *Featured, british biography, Arts & Humanities, Charles Wiliams, Eagle and Child, Grevel Lindop, Sir Geoffrey Hill, The Allegory of Love, the inklings, Add a tag

It was strikingly appropriate that Sir Geoffrey Hill should have focused his final lecture as Oxford Professor of Poetry on a quotation from Charles Williams. Not only was the lecture, in May 2015, delivered almost exactly seventy years after Williams’s death; but Williams himself had once hoped to become Professor of Poetry.

The post Charles Williams: Oxford’s lost poetry professor appeared first on OUPblog.

Blog: The Mumpsimus (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

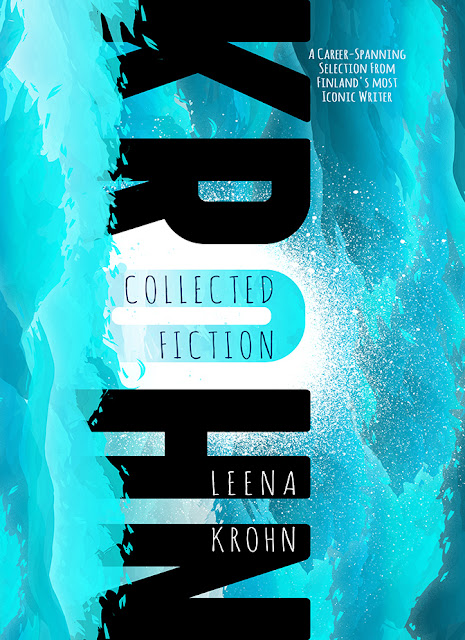

JacketFlap tags: books, fiction, short stories, Writers, novels, Leena Krohn, Cheeky Frawg, Add a tag

The most peculiar property of language is its symbolic function. The writer exchanges meanings for marks, while the reader performs the opposite task. There are no meanings outside us, or if there are, we do not know them. Personal meanings are made with our own hands. Their preparation is a kind of alchemy. Everything that we call rationality demands imagination, and if we did not have the capacity to imagine, we could not even speak morality or conscience.Ann and Jeff VanderMeer have done wonders for the availability of contemporary Finnish writing in English with their Cheeky Frawg press, and in December they will release their greatest book yet: Collected Fiction by Leena Krohn.

—Leena Krohn, "Afterword: When the Viewer Vanishes"

I've been a passionate fan of Leena Krohn's work ever since I first read her book Tainaron ten years ago. I sought out the only other translation of her writings in English available at the time, Doña Quixote & Gold of Ophir, and was further impressed. I read Datura when Cheeky Frawg published it in 2013. It's all remarkable work.

Collected Fiction brings together all of those books, plus more: The Pelican's New Clothes (children's fiction from the 1970s, just as entrancing as her adult work later), Pereat Mundus (which I've yearned to read ever since Krohn mentioned it when I interviewed her), some excerpts and stories from various books published over the last 25 years, essays by others (including me) that give some perspective on her career, and an afterword by Leena Krohn herself.

This book is as important a publishing event in its own way as New Directions' release earlier this year of Clarice Lispector's Complete Stories. It's a similarly large book (850 pages), and though not Krohn's complete stories, it gives a real overview of her career and provides immeasurable pleasure.

|

| Leena Krohn |

In a helpful overview of the first thirty years of Krohn's writing (1970-2001) included here, Minna Jerman writes: "Gold of Ophir is constructed in such a way that you could easily read its chapters in any order, and have a different experience with each different sequence." This is true for most of Krohn's novels, it seems to me, and is another virtue of her writing, something that makes it feel so different from so many other books, so truly strange, and yet so captivating, like a puzzle that isn't especially insistent about its puzzle-ness — or, to quote the great John Leonard, it embodies "Chaos Theory, with lots of fractals."

This is what I want to tell you, then: Reader, you should get this book at the first opportunity and you should spend a year (at least!) reading through it in whatever order you feel like, letting it be a magical, mind-warping cabinet of curiosities, a wonderbox of a book. You should not devour Leena Krohn's writing. Savor it, take it in in small bits, because there are so many glorious small bits here. Why rush? This is rich, rich material. Just as no rational person would ever guzzle a truly fine scotch, so you should sip from Krohn's fountain of dreamwords.

And this is what I want to tell you, O Writerly Types: This book is a gift to you, a tome of possibilities. Stop writing like everybody else. We don't need you to make your vision fit into the airport bookstore shelves. Those shelves are full. We need more writers who will do what Leena Krohn has done, who will seize language as a tool for dreaming back toward consciousness, who will find forms that fit such dreaming, who will not replicate the conventions of now but instead reconfigure their own conventions until they seem inevitable. Learn from this book, O Writers. Let it inspire you to write in your own new ways, your own new forms, your own truthful imaginings.

In a trance, his hand already numb and senseless, accompanied by the rustle of the rain and the croaking of frogs, Håkan was taken through the eras toward the wondrous time when he did not yet exist.

—Leena Krohn, Pereat Mundus: A Novel of Sorts

Blog: Christine Marie Larsen Sketchbook (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: portraits, people, color, writers, editorial, faces, commissioned, SRoB, Add a tag

Each week I will feature a different author portrait in this new Seattle Review of Books column "Portrait Gallery."

Add a CommentBlog: Christine Marie Larsen Sketchbook (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: portraits, people, color, writers, editorial, commissioned, SRoB, Add a tag

Here's a portrait of Kate Beaton that was just published in The Seattle Review of Books. Each week I will feature a different author portrait in this new SRoB column "Portrait Gallery."

Add a CommentBlog: The Mumpsimus (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: William Plomer, UNH, Vera Brittain, Elizabeth Bowen, John Lehmann, Winifred Holtby, Writers, PhD, Christopher Isherwood, Woolf, Add a tag

The new school year has started, which means I've officially ended the work I did for a summer research fellowship from the University of New Hampshire Graduate School, although there are still a few loose ends I hope to finish in the coming days and weeks. I've alluded to that work previously, but since it's mostly finished, I thought it might be useful to chronicle some of it here, in case it is of interest to anyone else. (Parts of this are based on my official report, which is why it's a little formal.)

I spent the summer studying the literary context of Virginia Woolf’s writings in the 1930s. The major result of this was that I developed a spreadsheet to chronicle her reading from 1930-1938 (the period during which she conceived and wrote her novel The Years and her book-length essay Three Guineas), a tool which from the beginning I intended to share with other scholars and readers, and so created with Google Sheets so that it can easily be viewed, updated, downloaded, etc. It's not quite done: I haven't finished adding information from Woolf's letters from 1936-1938, and there's one big chunk of reading notebook information (mostly background material for Three Guineas) that still needs to be added, but there's a plenty there.

Originally, I expected (and hoped) that I would spend a lot of time working with periodical sources, but within a few weeks this proved both impractical and unnecessary to my overall goals. The major literary review in England during this period was the Times Literary Supplement (TLS), but working with the TLS historical database proved difficult because there is no way to access whole issues easily, since every article is a separate PDF. If you know what you’re looking for, or can search by title or author, you can find what you need; but if you want to browse through issues, the database is cumbersome and unwieldy. Further, I had not realized the scale of material — the TLS was published weekly, and most reviews were 800-1,000 words, so they were able to publish about 2,000 reviews each year. Just collecting the titles, authors, and reviewers of every review would create a document the length of a hefty novel. The other periodical of particular interest is the New Statesman & Nation (earlier titled New Statesman & Athenaeum), which Leonard Woolf had been an editor of, and to which he contributed many reviews and essays. Dartmouth College has a complete set of the New Statesman in all its forms, but copies are in storage, must be requested days in advance, and cannot leave the library.

All of this work could be done, of course, but I determined that it would not be a good use of my time, because much more could be discovered through Woolf’s diaries, letters, and reading notebooks, supplemented by the diaries, letters, and biographies of other writers. (As well as Luedeking and Edmonds’ bibliography of Leonard Woolf, which includes summaries of all of his NS&N writings — perfectly adequate for my work.)

And so I began work on the spreadsheet. Though I chronicled all of Woolf’s references to her reading from 1930-1938, my own interest was primarily in what contemporary writers she was reading, and how that reading may have affected her conception and structure of The Years and, to a lesser extent, Three Guineas (to a lesser extent because her references in that book itself are more explicit, her purpose clearer). As I began the work, I feared I was on another fruitless path. During the first years of the 1930s, Woolf was reading primarily so as to write the literary essays in The Common Reader, 2nd Series, which contains little about contemporary writing, and from the essays themselves we know what she was reading.

But then in 1933 I struck gold with this entry from 2 September 1933:

I am reading with extreme greed a book by Vera Britain [sic], called The Testament of Youth. Not that I much like her. A stringy metallic mind, with I suppose, the sort of taste I should dislike in real life. But her story, told in detail, without reserve, of the war, & how she lost lover & brother, & dabbled her hands in entrails, & was forever seeing the dead, & eating scraps, & sitting five on one WC, runs rapidly, vividly across my eyes. A very good book of its sort. The new sort, the hard anguished sort, that the young write; that I could never write. (Diary 4, 177)Vera Brittain’s Testament of Youth was published in 1933, and was one of the bestselling books of the year. It remains in print, and a film of it was in US theatres this summer. What struck me in Woolf’s response to it was that she called it a book “I could never write” — and she did so just as The Years was finding its ultimate form in her mind, and only months before she started to write the sections concerned with World War One. What also struck me was that her response to Testament of Youth was in some ways similar to her infamous response to Joyce’s Ulysses, a book she thought vulgar and a bit too obsessed with bodily functions, but which also clearly fascinated and influenced her.

One of the things that occurred to me after reading Woolf’s note on Testament of Youth was that The Years is among her most physically vivid novels. Sarah Crangle has said of it: “The Years is a culminating point in Woolf ’s representation of the abject, as she incessantly foregrounds the body and its productions” (9). The September 2 diary entry shows that Woolf was highly aware of this foregrounding in Vera Brittain’s (very popular) book, and her framing of herself as part of an older generation and someone unable to write in such a way may have worked as a kind of challenge to herself.

I then sought out Testament of Youth and read it (all 650 pages) with Woolf in mind. What qualities of this book caused it to run so rapidly across her eyes? She herself wrote in a letter to her friend Ethel Smyth on September 6: “Vera Brittain has written a book which kept me out of bed till I'd read it. Why?” (Letters 5, 223). I asked Why? myself quite a bit as I began reading Testament, because the first 150 pages or so are not anything a contemporary reader is likely to find gripping. And yet reading with Woolf in mind made it quite clear: The first section of Testament is all about Vera Brittain’s attempt to get into Oxford, and Woolf herself had been denied (because of her gender) the university education her brothers received, a fact that bothered her throughout her life. The ins and outs of Oxford entrance exams may not be scintillating reading for most people, but for a woman who had never even been able to consider taking those exams, and yet dearly yearned for an educational experience of the sort men were allowed, Testament provides a vivid vicarious experience. The central part of the book, about Brittain’s experience as a nurse during the war, also provided vicarious experience for Woolf, whose own experience of the war was far less immediate. Woolf lost some friends and distant relations in the war (most notably the poet Rupert Brooke, with whom she was friendly and may have had some romantic feelings for), but did not experience anything like the trauma that Brittain did: the loss of all of her closest male friends, including her fiancé and her brother. Nor did Woolf see mutilated bodies and corpses, as Brittain did.

Woolf and Brittain were very much aware of each other — Brittain, in fact, makes passing mention to A Room of One’s Own in Testament of Youth — and the first book-length study of Woolf in English was written by Brittain’s great friend Winifred Holtby (an important character in the latter part of Testament; after Holtby’s death in 1935, Brittain wrote a biography of her titled Testament of Friendship, which Woolf thought presented too flat a view of Holtby, a person she seems to have come to respect, though she didn’t much like Holtby’s writing). There is, though, very little scholarship on Woolf, Brittain, and Holtby together, perhaps because Brittain and Holtby seem like such different writers from Woolf in that they were much more committed to a kind of social realism that Woolf abjured. There's a lot of work still remaining to be done on the three writers together. Not only is Testament of Youth a book that can be brought into conversation with The Years, but Brittain’s novel Honourable Estate, published one year before The Years, has numerous similarities in its scope and goals to The Years, though it seems almost impossible that it had any direct influence, since it was published when Woolf was doing final revisions of The Years and she didn’t much like Brittain’s writing, so was unlikely to have read the book (I’ve certainly found no evidence that she did).

In the course of this research, I soon discovered that UNH’s own emerita professor Jean Kennard published a book in 1989 titled Vera Brittain and Winifred Holtby: A Working Partnership, the first (and still only) scholarly study of the two writers together. I read the book avidly, as I had taken a seminar on Virginia Woolf with Prof. Kennard in the spring of 1998 at UNH as an undergraduate, and I owe much of my love of Woolf to that seminar. The book looks closely at each authors’ writings and proposes that their friendship was a kind of lesbian relationship, an idea that has been somewhat controversial (Deborah Gorham’s study of Brittain offers a nuanced response).

In addition to exploring the connections and resonances between Woolf, Brittain, and Holtby, I looked at three writers of the younger generation whom Woolf knew personally and paid close attention to: John Lehmann, William Plomer, and Christopher Isherwood. Lehmann worked for the Woolfs at their Hogarth Press in the early thirties, left for a while, then returned and took a more prominent role, buying out Virginia Woolf’s share of the press in the late 1930s. Lehmann and the Woolfs had an often contentious relationship, as he was very interested in the work of younger writers, particularly poets, and Virginia Woolf especially had more mixed feelings about the directions that writers such as W.H. Auden and Stephen Spender were going in. Woolf wrote a relatively long letter to Spender on 25 June 1935 about his recent collection of criticism, The Destructive Element, in which she positions her own aesthetics both in sympathy and tension with Spender’s, particularly Spender’s perspective on D.H. Lawrence.

Spender’s defense of Lawrence helps explain some of Virginia Woolf’s resistance to the younger writer’s aesthetic. One of the insights that my work this summer provided (at least to me) was the extent to which Woolf thought about, and was bothered by, Lawrence, who died in March 1930. (In 1931, Woolf wrote "Notes on D.H. Lawrence", primarily about Sons and Lovers.) She had complex feelings about Lawrence’s writing — disgust, frustration, and annoyance mixed with fascination. She often said she hadn’t read much of Lawrence’s work, but from the amount of references she makes to it, and the number of critical studies and memoirs about Lawrence that she read and commented on, I don’t think her protestations of not having read much of Lawrence are quite accurate — she was clearly familiar with all his major novels, and I suspect that in her letters she downplayed this familiarity as a hedge against the strong feelings of correspondents who thought Lawrence to be among the greatest British novelists of the age. Lawrence’s work was very much on Woolf’s mind in the first years of the 1930s, and it therefore seems likely to me that The Years was also conceived as a kind of response to The Rainbow and Women in Love in particular. But that's more hunch than anything, and this is a topic for more study.

John Lehmann introduced Christopher Isherwood to the Woolfs, and encouraged them to publish his second novel, The Memorial, which they did. In 1935, they also published his first Berlin novel, Mr. Norris Changes Trains (in the US, The Last of Mr. Norris), then in 1937 his novella Sally Bowles and in 1939 the interlinked stories of Goodbye to Berlin (later to be adapted as the play I Am a Camera and the musical Cabaret). Isherwood’s experience of Berlin in the 1930s was of particular interest to the Woolfs, who themselves (with some trepidation, given the fact that Leonard was Jewish) traveled through Germany briefly in 1935 to see the extent of the spread of Nazism.

William Plomer was a writer the Woolfs published in 1926, and who became close friends with Lehmann, Isherwood, Auden, and Spender. Plomer was born to British parents in South Africa, attended schools in England, then returned to Johannesburg, where he finished college and then worked as a farmhand and then with his family at a trading post in Zulu lands. It was there that he wrote Turbott Wolfe, based partly on his experience at the trading post and partly on his friendships among painters and artists in Johannesburg. He was only 20 years old when he sent it to the Woolfs, and they printed it soon after Mrs. Dalloway. Leonard was particularly interested in African politics and anti-imperialism, and the novel’s theme of racial mixing as a solution to the tensions between races in South Africa was iconoclastic and proved controversial. Plomer left South Africa and spent time in Japan, experiences which informed his later novel (also published by the Woolfs) Sado, a story that included homosexual overtones. (Like Lehmann, Isherwood, Auden, and Spender, Plomer was gay, though less openly and comfortably so than his friends.) Plomer would publish a number of books with the Woolfs, including some well-received volumes of poetry, but eventually moved to publish his fiction and autobiographies with Jonathan Cape, where he was an editorial reader (and convinced Cape to publish the first novel of his friend Ian Fleming, Casino Royale — a very young Fleming, in fact, had written Plomer a fan letter after reading Turbott Wolfe, the two became friends when Fleming was a journalist in the 1930s, and eventually Fleming dedicated Goldfinger to Plomer).

Plomer became a more frequent member of the Woolf’s social circle than any other young writer that I’ve noticed, and Virginia Woolf seems to have felt almost motherly toward him. Aesthetically, he was far less threatening than the other young men of the Auden generation, and though his novels can easily be read through a queer frame, he was more circumspect about the topic than his peers.

As the summer wound down and I continued to work through Woolf’s diaries and letters, I became curious about the place of Elizabeth Bowen’s work in her life. Woolf and Bowen were friends, and Bowen’s work shows many Woolfian qualities, but Woolf made very few conclusive statements about Bowen’s novels that I have been able to find so far — mostly, she acknowledge Bowen sending her each new novel, and always said she would read it soon, but I have only found definite evidence that she read one, The House in Paris, which is set soon after World War I and, like Mrs. Dalloway, takes place over the course of a single day. Like the connections and resonances between Woolf, Brittain, and Holtby, the relationship between the works of Woolf and Bowen seems to be ripe for further study.

But the summer has ended, and my studies must now move toward my Ph.D. qualifying exams, so the British writers of the 1930s, as fascinating as they were, must move now to the background as I widen my view toward everything there is to say and know about modernism, postcolonial studies, and queer studies... Read the rest of this post

Blog: The Mumpsimus (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: birthdays, Writers, Tiptree, Add a tag

Alice Sheldon was born 100 years ago today, which means that in a certain sense, James Tiptree, Jr. is 100, because Sheldon wrote under that name. Yet James Tiptree, Jr. wasn't really born until 1968, when the first Tiptree story, "Birth of a Salesman", appeared in the March issue of Analog.

Nonetheless, we can and should celebrate Sheldon's centenary. She's primarily remembered for Tiptree, of course, but as Julie Phillips so deftly showed in her biography, Sheldon's life was far more than just that byline.

I've written about Tiptree a lot over the years, though nothing recently, as other work has taken me in other directions. In honor of Alice Sheldon's birthday, here are some of the things I've written in the past—

- In "The Stories That Predict Us", I wrote about discovering Tiptree at an early age.

- I reviewed the selected Tiptree stories, Her Smoke Rose Up Forever, for SF Site in 2005. (It's a joint review with the first Tiptree Awards volume. I wish I'd just reviewed the Tiptree collection alone. That's the only part of the review worth reading now.)

- A very early post at this blog looked at "The Screwfly Solution", which was published under the other pseudonym, Raccoona Sheldon. (11+ years after writing that post, I still think the story's ending is ruined by its final sentence.)

- I wrote about Tiptree's first novel, Up the Walls of the World, in 2009.

- In 2006, I interviewed Tiptree's biographer, Julie Phillips.

Blog: The Open Book (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: community, Book News, writing advice, writing contests, Diversity, writing, writers, Immigration, writing awards, Lee & Low Likes, New Voices/New Visions Award, Diversity, Race, and Representation, Guest Blogger Post, american immigration council, celebrate america, celebrate america writing contest, claire tesh, Add a tag

LEE & LOW BOOKS has two writing contests for unpublished authors of color: the New Voices Award, for picture book manuscripts, and the New Visions Award, for middle grade and young adult manuscripts. Both contests, which are now open for submissions aim to recognize the diverse voices and talent among new authors of color who might otherwise remain under the radar of mainstream publishing.

In this guest post, we wanted to highlight another groundbreaking writing contest that’s bringing attention to marginalized voices and fostering a love of writing in students: the Celebrate America Writing Contest run by the American Immigration Council. Coming into its 19th year, the Celebrate America Writing Contest for fifth graders has been bringing attention to the contributions of immigrants in America through the eyes and pens of our youngest writers.

In this guest post, Claire Tesh, Senior Manager of Education at the American Immigration Council, discusses the mission of the Celebrate America Writing Contest and how it has helped to shape the immigration narrative.

It is impossible to escape the negative vitriol and hateful rhetoric around the issue of immigration that dominates the headlines, talk radio, popular culture, and in some cases the dinner table. In an effort to educate children and communities about the value of immigration to our society The American Immigration Council teams up with schools and community groups to provide young people the resources and information necessary to think critically about immigration from both a historical and contemporary perspective, while working collaboratively and learning about themselves and their communities.

The American Immigration Council developed “Celebrate America,” an annual national creative writing contest for fifth graders, because they are at the age where they are discovering their place in the world both locally and globally. They are also finding their own voice, opinions and ideas through writing, creating and sharing. Students at this age start making sense of current events; they have a better working knowledge of basic history, and have a sense of global awareness.

Thousands of Entries

“Celebrate America” began 19 years ago with just a couple dozen entries. Today it has grown to over 5,000 entries annually! Since 1997 a total of close to 75,000 students have participated in two dozen cities, in nearly 750 schools and community centers across the nation.

As the lead on the contest since 2006, I have read thousands of entries and have attended numerous events featuring the writers. It is difficult to pick just one example, but in 2008 the winning entry America is a Refuge really showed how much a 10-12 year old can comprehend about the issue. That year, the winner, Cameron Busby, explained to a reporter from the Tucson Citizen that “I want to be a horror writer when I grow up,” and in order to tell the story of America being a place people come to be safe and thrive, he used bits and pieces of some of his classmate’s true horror stories of their own or their family member’s immigration journeys. This excerpt shows the young writer’s entry and how he made sense of injustice and how America has always been a nation symbolic as a beacon for hope:

A small child holds out a hoping

hand,

a crumb of bread,

or even a penny just to be fed

Hoping America is a refuge. A

child weeps over her mother’s

lifeless body,

the tears streaming down her

face

Praying America is a refuge.

Part of the reason why it’s a popular contest is because it fits neatly with the fifth grade curriculum and it is easy for teachers to implement by offering timely lessons and expository learning opportunities from classroom visits by experts to interactive web-based games. The contest is unique in that it allows for any written work that captures the essence of why the writer is proud that America is a nation of immigrants and students can express themselves through narrative, descriptive, expository, or persuasive writings, poetry, and other forms of written expressions. The teaching and learning opportunities the contest brings to both the classroom and the community has made it very popular and most teachers who participate do so year after year.In the Classroom

Monica Chun, a teacher from Seattle who has participated in the contest for several years and whose student, Erin Stark, was a national winner in 2013, starts the assignment by asking students to ask their relatives at home a question: “Who was the first person in our family to come to America?” No matter what ethnicity or how recent or distant a family’s arrival be, every student is going to have a unique answer to this question.

Involving the Community

”Celebrate America” encourages youth, families and surrounding communities to evaluate and appreciate the effects of immigration in their own lives. The unique contest includes the following components:

- Immigration attorneys or trained volunteers visit classrooms, whether in person or virtually. The visitors give short presentations about the history of American immigration and the contributions immigrants have made over the years;

- Teachers complement the contest by implementing lessons about immigration, social justice and diversity into their curriculum;

- The American Immigration Council provides classrooms with innovative, relevant, and interactive lessons and resources;

- Communities organize events, naturalization ceremonies and other celebrations to showcase the local winners;

- The winning entry from each locale is sent to the national office and judged by well-known journalists, immigration judges and award winning authors;

- The winning entry is read into the Congressional record, a flag is flown over the Capitol in the winner’s honor and the winner reads their entry at a 700+ person event that celebrates immigration; and

- In the submissions the youth voice brings hope that there will be solutions to the immigration debate.

The American Immigration Council believes that teachers, parents, and students are essential to building a collective movement toward a better future: in our classrooms, in our schools, and in the larger society. With the community’s engagement, educators, parents and students can help bridge this divide and approach the issue of immigration with intelligence and empathy.

Contest Impact

The contest has an impact not only in the schools and communities that participate, but also in the halls of Congress. Each year when the winning entry is read into the Congressional Record, it is rewarding to know that our leaders are hearing words of wisdom from a young person who has big ideas and who has chosen to use their voice to invite others to learn about immigration and to celebrate America’s diversity.

When the winning entries are read to new citizens at naturalization ceremonies or at dinner galas in communities of all sizes, almost every attendee has tears in their eyes because the young readers are speaking from their hearts and they represent the future. Each and every year the young writers continue to surprise us with the depth and empathy in their writings whether it is their common sense solutions to an immigration system or the story of their own immigrant background. Any writer, no matter how old and how experienced, should look at these entries to get a sense for authentic voice and various styles of writing. The thousands of students who submit to the contest get recognized in their communities and the affect is exponential because students start in the classroom and their voice continues to be shared within their schools, within their communities and beyond.

The students participating in “Celebrate America” are America’s future citizens, voters, educators and activists and it is truly an honor to shape the contest so that it provides some of the tools to think critically about immigration and to learn to explore the economic and moral effects of immigration policy as they engage in the public debates. But, today as we try to navigate the complicated maze that is immigration law and policy, it is through their incredible choice of words, that they are our guides, our teachers, and our voices of reason.

For further information on eligibility and submission process:

- New Voices Award and New Visions Award (both for adults) from LEE & LOW BOOKS—If you are nervous about submitting your manuscript to the Awards, read these winning submissions written by 5TH GRADERS for inspiration

- Celebrate America Writing Contest (for fifth graders) from American Immigration Council

- Awards and Grants for Authors of Color

Blog: TWO WRITING TEACHERS (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: publishing, writing process, editing, writing, process, writers, revision, writing workshop, Pens, Pencils, notebooks, mistakes, drafting, routines, risk-taking, independent writing, growth mindset, Erasing, Add a tag

When I visit a classroom, one of the first things I often say to kids is, "Today, please don't erase. I want to see ALL the great work you are doing as a writer. When you erase, your work disappears!" Often, this is what kids are accustomed to and they continue working away. But sometimes, kids stare at me as if I've got two heads. ![]()

Blog: The Renegade Writer (Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags: Writing, Motivation, Advice, Writers, freelance writing, writing classes, writing gigs, writing trivia, Add a tag

Are You a Writing Fangirl…Or a REAL Writer? 7 Ways to Tell

Are You a Writing Fangirl…Or a REAL Writer? 7 Ways to Tell

We writers can spend hours every day thinking, dreaming, talking, and ruminating about writing. We love what we do!

But when we use these activities (and I’m loathe to even call them “activities”) as substitutes for actually writing…that’s a problem. We leave the realm of serious writer and enter the realm of — fanfolk.

And it’s a sneaky problem, because geeking out over all things writing feels like we’re being productive. We call it brainstorming, networking, getting motivated, whatever. But what it is not, is WRITING. Oh yeah, and MARKETING. And otherwise getting off our butts and going after, and completing, paying writing assignments.

(Caveat: I’m not saying we’re not allowed to have fun, kill time, and kibitz on writers’ forums. It’s when these time-wasters placate us into feeling productive — or we’re more interested in the trappings of a writer than in writing itself — that there’s a problem. )

Seven Signs You’re a Writing Fanboy/Girl:

1. You wear your Grammar Police badge with pride.

Writing forums, email discussion boards for writers, and blog comments are full of posts like these:

- My client just sent me an email where he used ‘their’ instead of ‘they’re’! *headdesk*

- Look at the typo in this newspaper headline! What is journalism coming to these days?

- Hey, blogger…you call yourself a writer? There’s a word missing in the second paragraph.

Pointing out/kvetching about other writers’ grammar mistakes make you FEEL good because hey, you don’t make mistakes like that so clearly you’re a superior writer. But is it getting you more gigs? Is it getting more writing out of you? Or is it simply wasting energy you could be using to get more assignments?

The person who made the typo is writing. What are YOU doing?

I have a guest post on the MakeaLivingWriting.com blog that goes into much, much more details on why you want to pit away your Grammar Police badge. (With 177 comments…clearly a hot button topic!)

2. You give a crap that The Comedy of Errors is Shakespeare’s shortest play. (And you know that it has 1,787 words.)

Look on almost any writers’ forum and you’ll see long threads where writers discuss their favorite pen (who writes in pen anymore?), post interesting factoids about Shakespeare, share motivational quotes from Hemingway, and hash out the details of the latest plagiarism/book banning/angry-author-screwed-by-publisher case.

I call these “fanboy writer posts.” These writer trivia posts show you’re a big fan of all things writing…but do they actually count as writing?

3. You’re a member of 10 writing organizations.

Here’s your email sig line:

Jane Smith, Wordsmith Extraordinaire

Member of:

National Writers Union

Science Writers of America

Mystery Writers Association

Medial Journalists’ Society

East Podunk Stitch & Bitch Writing Club

Romance Writers of America

[Add five more here]

Guess what? Editors and potential clients do not look at this list and say, “Wow. She must be a serious writer. Let’s hire her!”

Being a member of (most) writers’ associations does not prove that you are a writer. If you shell out your $150, you can get in. Even if you’ve never written a word in your life!

Join the organizations that pertain to the exact type of writing you’re actually doing. Not the genres you wish you were in, or the ones you think will impress people. And only join if you plan to be active in the group (which includes — wait for it — writing.)

4. You are the proud owner of a vast collection of quill pens.

Many writers love the trappings of writing more than the actual act of writing itself. So we see aspiring writers posting photos of their collection of mugs with writerly sayings; getting/talking about/comparing/sharing on social media their tattoos of Remington typewriters; collecting recycled-paper, leather-bound journals (just for looking at, natch); and strolling the aisles of Office Depot coveting the fancy pens.

Anyone looking at you, with your exclamation point tattoo and “Writer at Work” doorknob hanger, would think you are a writer. But…are you actually writing? Don’t delude yourself: A collection of quill pens does not a writer make.

5. You take writing classes you don’t need.

Wait a minute…did I just say that? Maybe I’m shooting myself in the foot because I teach a ton of classes for writers here—but seen too many writers take class after class in order to avoid having to actually pitch and write.

(Many instructors LOVE students like that…they pay good money, don’t do the work, and the instructor gets something for nothing.)

A multitude of certificates from writing classes is the sign of an insecure writer who always thinks she needs to know more before getting started — or the sign of fanfolk who love showing off their creds more than they do actually writing.

Yes, take a class to learn the skills you’re lacking, whether it’s writing the perfect pitch, running a writing business, or crafting an article that will sell. Then…go out and do that thing. That’s what makes you a real writer. If you come to a a roadblock because you need more skills, THEN you can take more classes.

This goes for free classes, too. Just about everyone with something to sell online offers a free class/instructional webinar/training call to get people on their email lists. It’s tempting to try them all! But unless you need that exact skill right now, you can hold off until you do.

6. You love books.

Writers love spending lots of time on Goodreads reviewing books. And weighing in on the latest literary controversies (is The Goldfinch crap or not?) And discussing On Writing and Writing Down the Bones and The Artist’s Way. And bragging about how many books they have in their homes. (I have over 1,000 books! Oh yeah? Well, I have 1,500. Here’s a photo to prove it!)

But the fact that you have a library overflowing with books, a shelf full of writing manuals, and 500 Goodreads reviews (especially of those writing manuals!) does not show you’re a writer. You talk a good game, but do you have the ass-in-seat-time to prove it? Serious writers with limited time use their time to — write.

7. You call yourself a “scribe” or “wordsmith” on your business card.