There are so many reports of agents that may cause cancer, that there is a temptation to dismiss them all. Tabloid newspapers have listed everything from babies, belts, biscuits, and bras, to skiing, shaving, soup, and space travel. It is also tempting to be drawn into debates about more esoteric candidates for causative agents like hair dyes, underarm deodorants, or pesticides.

The post Let’s refocus on cancer prevention appeared first on OUPblog.

Imagine the thrill of discovering a new species of frog in a remote part of the Amazon. Scientists are motivated by the opportunity to make new discoveries like this, but also by a desire to understand how things work. It’s one thing to describe the communities of microorganisms in our guts, but quite another to learn what causes these communities to change and how these changes influence health.

The post Complexities of causation appeared first on OUPblog.

I have been meaning to ready Megan Abbott for ages. I’ve only heard good things, in particular her latest books, so thought I’d begin with her brand new novel. Abbott’s last few novels have all been set in the world of teenage girls, a world she has been exploring because ‘Noir suits a 13-year-old girl’s mind’

I have been meaning to ready Megan Abbott for ages. I’ve only heard good things, in particular her latest books, so thought I’d begin with her brand new novel. Abbott’s last few novels have all been set in the world of teenage girls, a world she has been exploring because ‘Noir suits a 13-year-old girl’s mind’

Not only is The Fever a fantastic noir crime novel but it is a great exploration of the secrets and lies of teenage life and the hysteria that can so easily get whipped up now in a world of social media, Google and 24 hour news.

One morning in class Deenie’s best friend Lise is struck down by what seems to be a seizure, she is later rushed to hospital and put on life support. Nobody knows what caused the seizure. When other girls are struck down with similar symptoms confusion quickly turns to hysteria as parents and authorities scramble for answers. Are the recent student vaccinations to blame? Or is it environmental? And what steps are authorities taking to protect other children?

Abbott tells the story from one family’s point of view alternating between Tom, a teacher at the school, his son Eli, who is the object of a lot of girls’ affections and younger daughter Deenie, whose best friend Lise is the first girl struck down with this mysterious ailment. Each point of view is almost a different world giving not only a different perspective to the story but a different emotional intensity and sense of urgency.

The secrets and lies of teenage lives coupled with the paranoid and hysterical nature of parenting in the 21st century make for a truly feverish and wickedly noir-ish read.

By Janet R. Gilsdorf

Every April, when the robins sing and the trees erupt in leaves, I think of Brad — of the curtain wafting through his open window, of the sounds of his iron lung from within, of the heartache of his family. Brad and I grew up at a time when worried mothers barred their children from swimming pools, the circus, and the Fourth of July parade for fear of paralysis. It was constantly on everyone’s minds, cast a shadow over all summertime activities. In spite of the caution, Brad got polio — bad polio, which further terrorized our mothers. It still haunts me. If, somehow, he had managed to avoid the virus for a couple years until the Salk vaccine arrived, none of that — the iron lung, the shriveled limbs, the sling to hold up his head — would have happened.

In 1954, many children in my town, myself included, became “Polio Pioneers” because our parents made us participate in the massive clinical trial of the Salk vaccine. Some of us received the shot of killed virus, others received a placebo. We were proud, albeit scared, to get those jabs, to be part of a big, important experiment. Our moms and dads would have done anything to rid the country of that dreaded disease.

Because the vaccine is so effective, mothers today aren’t terrified of polio. Children in our neighborhoods aren’t growing up in iron lungs or shuffling to school in leg braces. We seem so safe. But our world is smaller than it used to be. The oceans along our coasts can’t stop a pestilence from reaching us from abroad. A polio virus infecting a child in Pakistan, Nigeria, or Afghanistan can hop a plane to New York or Los Angeles or Frankfurt or London, find an unimmunized child, and spread to other unimmunized people. Our earth is not yet free of polio.

Germs are like things that go bump in the night. They can’t been seen, they lurk in familiar places, they are sometimes very harmful, and they instill great fear—some justified, some not.

Fear of measles, like fear of polio, is justified. In the old days, one in twenty children with measles developed pneumonia, one or two in a thousand died. The vaccine changed all that in the developed world. But, measles continues to rage in underdeveloped countries. In a race for very high contagiousness, the measles virus ties the chickenpox virus (which causes another vaccine-preventable childhood infection). Both viruses can catch a breeze and fly. Or they may linger in still air for over an hour. They, too, ride airplanes. This year alone, outbreaks of measles started by imported cases have occurred in New York, California, Massachusetts, Washington, Texas, British Columbia, Italy, Germany, and Netherlands.

Fear of whooping cough (aka pertussis) is also justified. In the pediatric hospital where I work, two young children have died of this infection in the past several years and many others have suffered from the disease, which used to be called “the one-hundred day cough.” It lasts a long time and antibiotic treatment does nothing to shorten the course. Young children with pertussis may quit breathing, have seizures, or bleed into their eyes. It spreads like invisible smoke around high schools and places where people gather … and cough on each other.

On the other hand, fear of vaccines — immunizations against measles, polio, chickenpox, or whooping cough — is hard to understand. In the grand scheme of things, any of these serious infections is a much greater threat than the minimal side effects of a vaccine to prevent them. Just ask the mothers of the children who died of pertussis in my hospital. It’s true that the absolute risk of these infections in resource rich areas is small. But, for even rare infections, a 0.01% risk of disease translates into hundreds of healthy children who don’t have to be sick, or worse yet die, of a preventable infection.

In spite of the great success of vaccines, they aren’t perfect. Perfection is a tall order. Still we can do better. Fortunately, because of the work of my medical and scientific colleagues, new vaccines under development hold promise to be more effective with fewer doses, to provide increased durability of vaccine-induced immunity, and to be even freer of their already rare side effects. And, we’re creating vaccines against respiratory syncytial virus, Staphylococcus aureus, group A Streptococcus, herpes virus, and HIV, to name a few.

Brad would be proud of how far we have come in protecting our children from the horrible affliction that crippled him. He’d also be furious at our failure to vaccinate all our children. Every single one of them. He’d tell us that no child should ever be sacrificed to the ravages of polio or measles or chicken pox or whooping cough.

Janet R. Gilsdorf, MD is the Robert P. Kelch Research Professor of Pediatrics at the University of Michigan Medical School and pediatric infectious diseases physician at C. S. Mott Children’s Hospital, Ann Arbor. She is also professor of epidemiology at the University of Michigan and President-elect of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society. Her research focuses on developing new vaccines against Haemophilus influenzae, a bacterium that causes ear infections in children and bronchitis in older adults. She is the author of Inside/Outside: A Physician’s Journey with Breast Cancer and the novel Ten Days.

To raise awareness of World Immunization Week, the editors of Clinical Infectious Diseases, The Journal of Infectious Diseases, Open Forum Infectious Diseases, and Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society have highlighted recent, topical articles, which have been made freely available throughout the observance week in a World Immunization Week Virtual Issue. Oxford University Press publishes The Journal of Infectious Diseases, Clinical Infectious Diseases, and Open Forum Infectious Diseases on behalf of the HIV Medicine Association and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), and Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society on behalf of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society (PIDS).

The Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society (JPIDS), the official journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, is dedicated to perinatal, childhood, and adolescent infectious diseases. The journal is a high-quality source of original research articles, clinical trial reports, guidelines, and topical reviews, with particular attention to the interests and needs of the global pediatric infectious diseases communities.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: Vaccination. © Sage78 via iStockphoto.

The post Vaccines: thoughts in spring appeared first on OUPblog.

By Miranda Payne

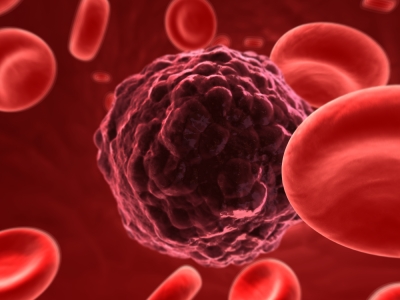

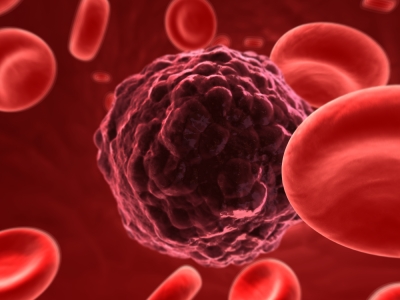

Oncologists have long known that one patient is not the same as another. Indeed one patient’s cancer is not the same as another’s. Regardless of apparent clinical similarities, doctors witness huge variations in rates of cancer progression and patients’ response to treatment. There is increasing understanding of the need to investigate the multiple molecular differences between cancers, which may predict differences in patterns of growth and spread, and assist in the selection of the most effective treatments, whilst avoiding treatment in those unlikely to benefit. These molecular differences can evolve during the course of a patient’s disease, so that the cancer from which a patient might die may be very different to the one with which they were originally diagnosed. Exciting as these advances are, they bring into stark relief just how difficult the challenges faced by the patient and their oncologist are: how to develop treatments to which the individual’s particular cancer is likely to respond, and how to mount a re-challenge should it evolve.

In recent years, cancer immunotherapy has returned to the forefront of cancer research. This aims to exploit the power and targeted response of the patient’s own immune system to fight their cancer. Resurgence in interest has been prompted particularly by developments in the management of malignant melanoma, a type of skin cancer as well as kidney cancers, along with exciting clinical trial data in patients with lung cancer. Many patients with a diagnosis of secondary melanoma now routinely have access to the anti-cancer treatment ipilimumab, an antibody which triggers a specific response from a sub-group of the patient’s own white blood cells (called cytotoxic T-cells). One role of these T-cells is to recognise and kill cancerous cells, but to protect the rest of the body from unnecessary attack, this response is usually dampened down. Ipilimumab ‘releases the brakes’ from the immune system, speeding up the reaction time and growth of the T-cells. For a small minority of patients with secondary melanoma this can result in control of their tumour, sometimes lasting years, offering a tantalising insight into the potential of the immune system to eliminate cancerous cells. But the majority of patients derive no benefit, yet may suffer the multi-organ side-effects of the drug and the average survival with secondary melanoma continues to be measured in months.

How then to provoke the immune system more consistently and more specifically? Following successes with vaccinations against infectious diseases, there has been inevitable long-standing interest in the concept of vaccination to provoke a useful reaction against established cancers. Despite numerous avenues of research, little has translated into clinical practice. A solitary ‘therapeutic cancer vaccine’ currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for use in asymptomatic patients with hormone-resistant secondary prostate cancer has yet to find its place in the routine management of this disease.

Particular recent research focus has been on the role of the dendritic cell within the immune system, a cell derived from the bone marrow which captures ‘foreign’ material and is highly efficient at presenting it to T-cells, effectively launching the immune system to target the ‘foreign’ material. Earlier this year the BBC reported on a clinical trial underway in patients with glioblastoma, a brain tumour typically with a dismal prognosis and a low chance of responding to standard treatment options. There are over ten published small-scale studies performed along similar lines which, collectively, hint sufficiently at improved outcomes to justify expanding recruitment to several hundred patients. A sample of each patient’s tumour has been mixed with a sample of their own dendritic cells, before re-injection at intervals over a two year period. Each patient’s injection is a unique blend of their own cancer and their own immune cells, reintroduced to their immune system in the hope of educating it both to recognize their cancer as a target for destruction — and to remember that cancer, should it re-emerge in the future.

Results of this individualised cancer vaccine in patients with brain tumours are awaited, but the drive for evidence-based personalised cancer therapy has already advanced routine oncology practice. For instance, a patient’s breast cancer can be risk-stratified by analysis of a panel of mainly cancer-related genes. This can help the patient decide with their oncologist whether chemotherapy is the right treatment for them.

Future years will see rapid expansion in the concept of personalised cancer care, likely to encompass all aspects of the patient’s pathway, from diagnosis to treatment. The latest emerging concept is the ‘Mouse Avatar’ – the implanting of a sample of a patient’s cancer into an immunodeficient mouse to provide a personalized, living and reproducing model of that patient’s unique cancer. In theory this could enable oncologists to offer treatment to patients for which there is evidence of response in ‘their’ mouse. In reality, this technology remains in the earliest stages of development and multiple hurdles can be anticipated; scientific, financial and even ethical. Huge leaps are required before there is any prospect of it becoming a reality for the vast numbers of cancer patients requiring treatment each year.

But we have begun the journey towards the goal of personalised cancer care. Just as doctors should endeavour to treat each patient as unique, it seems possible that one day oncologists may be able to treat each patient’s cancer as unique too.

Miranda Payne is a Locum Consultant in Medical Oncology at the Oxford University Hospitals NHS Trust, specializing in the treatment of malignant melanoma, gynaecological and breast cancers. She took a first in Physiological Sciences at Oxford University and obtained her DPhil in Medical Oncology from Oxford University in 2010. Along with Jim Cassidy, Donald Bissett, and Roy Spence, she has been editor of the Oxford Handbook of Oncology for ten years and more recently, the Oxford American Handbook of Oncology (with Gary Lyman).

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Image credit: cancer cell – closeup. Image by Eraxion, iStockphoto.

The post Cancer therapy: now it’s getting personal appeared first on OUPblog.

By Lauren Pecorino

There is a tendency to complain about policies when writing blogs, but I think it is time to commend the British campaigns and innovations in treatment. They have proven to be some of the best in the world and have had a major impact in the fight against cancer.

One of the best British campaigns is against cervical cancer. Getting personally posted invitations to attend your next PAP screening, supported by pamphlets of information, is something few women ignore. Those who try to ignore these invitations are rightly and relentlessly bombarded with regular reminders.

And, with the knowledge that a sexually transmitted virus, Human Papilloma Virus (HPV), is responsible for all cases of cervical cancer, the UK implemented a national school-based HPV vaccination programme that has proven to yield high uptake. By 2009, 70 percent of 12-13 year olds in the UK were fully vaccinated. These results are admirable compared to the results of alternative on-demand provisions offered by other countries including the USA. Note that the vaccine is recommended for early teens as it is a preventative vaccine and not a therapeutic vaccine, and must be administered before the initiation of sexual activity for it to be effective. The vaccine prevents about 70% of cervical cancers caused by two specific strains of HPV. PAP screening is still important to catch cases that are not prevented by the vaccine. An added bonus of this campaign is that the same vaccine also protects against some head, neck, and anal cancers caused by HPV infections.

Another great British effort is towards the prevention of lung cancer. The anti-smoking adverts have been haunting, especially the most recent one released by the UK Department of Health that shows a tumor growing on a cigarette. It is brilliant. I wish I had designed it. The advert strikingly conveys the message that if you saw the damage smoking causes, you would not smoke. The percentage of male cigarette smokers have fallen from 55% in 1970 to 21% in 2010 and a decreasing number of deaths due to lung cancer has followed this trend.

Click here to view the embedded video.

The UK is also a model of good practice in that it is the only country in the world which has a network of free ‘stop-smoking’ services, recently supported by specialized training for National Health Service Stop Smoking practitioners.

We can help the national campaign at a personal level by being more opinionated and outspoken when it comes to letting those around us know that smoking is harmful and “uncool”- especially among the young. We must ensure the message is passed down to new generations.

Finally, the UK is at the leading edge in using stem cells to help replace organs damaged by cancer. Tracheal transplants using tracheal scaffolds from cadavers seeded with the patient’s own stem cells have been used to replace damaged tissue for patients with tracheal cancer. Currently scientists at University College London are developing very similar procedures to grow a new nose for a patient who had lost their nose to cancer. These innovative approaches are the result of a continuously open, well-supported but regulated stem cell research policy, not yet seen in the USA.

Well done Great Britain!

Lauren Pecorino received her PhD from the State University of New York at Stony Brook in Cell and Developmental Biology. She crossed the Atlantic to carry out a postdoctoral tenure at the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, London. She is a Principal Lecturer at the University of Greenwich where teaches Cancer Biology and Therapeutics. The teaching of this course motivated her to write The Molecular Biology of Cancer: Mechanisms, Targets, and Therapeutics, now in its second edition. Feedback on the textbook posted on Amazon from a cancer patient drove her to write a book on cancer for a wider audience: Why Millions Survive Cancer: the Successes of Science.

Lauren Pecorino received her PhD from the State University of New York at Stony Brook in Cell and Developmental Biology. She crossed the Atlantic to carry out a postdoctoral tenure at the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, London. She is a Principal Lecturer at the University of Greenwich where teaches Cancer Biology and Therapeutics. The teaching of this course motivated her to write The Molecular Biology of Cancer: Mechanisms, Targets, and Therapeutics, now in its second edition. Feedback on the textbook posted on Amazon from a cancer patient drove her to write a book on cancer for a wider audience: Why Millions Survive Cancer: the Successes of Science.

Read a World Cancer Day Q&A with Lauren Pecorino.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only health and medicine articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

The post World Cancer Day 2013: The Best of British appeared first on OUPblog.