new posts in all blogs

Viewing: Blog Posts Tagged with: Metaphysics, Most Recent at Top [Help]

Results 1 - 11 of 11

How to use this Page

You are viewing the most recent posts tagged with the words: Metaphysics in the JacketFlap blog reader. What is a tag? Think of a tag as a keyword or category label. Tags can both help you find posts on JacketFlap.com as well as provide an easy way for you to "remember" and classify posts for later recall. Try adding a tag yourself by clicking "Add a tag" below a post's header. Scroll down through the list of Recent Posts in the left column and click on a post title that sounds interesting. You can view all posts from a specific blog by clicking the Blog name in the right column, or you can click a 'More Posts from this Blog' link in any individual post.

By: Franca Driessen,

on 9/24/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Graham Priest,

philosophy of mind,

Arts & Humanities,

Alexius Meinong,

noneism,

Towards Non-Being,

Books,

Philosophy,

logic,

semantics,

metaphysics,

*Featured,

Bertrand Russell,

Add a tag

Alexius Meinong (1853-1920) was an Austrian psychologist and systematic philosopher working in Graz around the turn of the 20th century. Part of his work was to put forward a sophisticated analysis of the content of thought. A notable aspect of this was as follows. If you are thinking of the Taj Mahal, you are thinking of something, and that something exists.

The post The strange case of the missing non-existent objects appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Franca Driessen,

on 7/23/2016

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Philosophy,

time,

physics,

reality,

metaphysics,

*Featured,

Simon Prosser,

Arts & Humanities,

philosophy of time,

temporality,

Experiencing Time,

Add a tag

Suppose you had to explain to someone, who did not already know, what it means to say that time passes. What might you say? Perhaps you would explain that different times are arranged in an ordered series with a direction: Monday precedes Tuesday, Tuesday precedes Wednesday, and so on.

The post Is it possible to experience time passing? appeared first on OUPblog.

|

Celtic celebration of Samhain,

or Halloween, where a door opens

briefly to the other world. |

Perhaps one of the most profound mysteries we are confronted with might be simply stated as "why is there something instead of nothing?" Countless philosophers, theologians, and scientists have addressed this question, some from the seemingly unprovable first cause principle--a prime mover, or God. Others, most often the scientists, are apt to point out we just are not there yet, but look how far we've already come in understanding our universe. We can even demonstrate all that exists today, starting from a distant Big Bang event, which happened some 14 billion years ago, and the complete, scientific answer is just around the corner.

Well, since this is a fiction writer's blog we are hesitant to delve too deeply into the philosophical or rhetorical arguments that support either camp. However, might we sometimes ponder about what view of God's existence was held by certain characters in our reading? If the author had had an opportunity to seamlessly integrate a spiritual viewpoint in the fiction, might it have given even greater depth, some flesh and bones, to the character, and the choices he makes in the story?

Some of this thought process springs from the reading of

The March, by E. L. Doctorow. The historical fiction covers the devastating Civil War march through the southern heartland, by General William Tecumseh Sherman. Sherman's army of about 60,000 Union soldiers carried out a scorched earth campaign through Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina, as the war neared a close and a collapse of the Confederacy. Like many, if not most, soldiers in either army, it seems safe to assume from writings of that era that the existential view of the combatants was Christian, fundamental Protestantism. However, most of the officers of that conflict were trained at West Point Academy, which would have had a tradition from the Founding Fathers of the U.S. for a belief in God, but not necessarily in a dogma of any established religion. And so the concepts of sin, resurrection, and eternal life in heaven, may not have been the uniform view of officers from the Academy. It was rewarding to read the following, given as internal dialogue of Gen. Sherman before the battle of Savannah:

But these troops, too, who have battled and eaten and drunk and fallen asleep with some justifiable self-satisfaction: what is their imagination of death who can lie down with it? They are no more appreciative of its meaning than I...

In this war among the states, why should the reason for the fighting count for anything? For if death doesn't matter, why should life matter?

But of course I can't believe this or I will lose my mind. Willie, my son Willie, oh my son, my son, shall I say his life didn't matter to me? And the thought of his body lying in its grave terrifies me no less to think he is not imprisoned in his dreams as he is in his coffin. It is insupportable, in any event.

It is in fear of my own death, whatever it is, that I would wrest immortality from the killing war I wage. I would live forever down the generations.

And so the world in its beliefs snaps back into place. Yes. There is now Savannah to see to. I will invest it and call for its surrender. I have a cause. I have a command. And what I do I do well. And, God help me, but I am thrilled to be praised by my peers and revered by my countrymen. There are men and nations, there is right and wrong. There is this Union. And it must not fall.

Sherman drank off his wine and flung the cup over the entrenchment. He lurched to his feet and peered every which way in the moonlight. But where is my drummer boy? he said.

And where else might a writer also go to study a moving portrayal of the metaphysical views of a major literary character in American literature: perhaps

Moby Dick, by Herman Melville:

"What is it, what nameless, inscrutable, unearthly thing is it; what cozening, hidden lord and master, and cruel, remorseless emperor commands me; that against all natural lovings and longings, I so keep pushing, and crowding, and jamming myself on all the time; recklessly making me ready to do what in my own proper, natural heart, I durst not so much as dare? Is Ahab, Ahab? Is it I, God, or who, that lifts this arm? But if the great sun move not of himself; but is as an errand-boy in heaven; nor one single star can revolve, but by some invisible power; how then can this one small heart beat; this one small brain think thoughts; unless God does that beating, does that thinking, does that living, and not I. By heaven, man, we are turned round and round in this world, like yonder windlass, and Fate is the handspike. And all the time, lo! that smiling sky, and this unsounded sea! Look! see yon Albicore! who put it into him to chase and fang that flying-fish? Where do murderers go, man! Who's to doom, when the judge himself is dragged to the bar? But it is a mild, mild wind, and a mild looking sky; and the air smells now, as if it blew from a far-away meadow; they have been making hay somewhere under the slopes of the Andes, Starbuck, and the mowers are sleeping among the new-mown hay. Sleeping? Aye, toil we how we may, we all sleep at last on the field. Sleep? Aye, and rust amid greenness; as last year's scythes flung down, and left in the half-cut swaths—Starbuck!"

But blanched to a corpse's hue with despair, the Mate had stolen away.

Ahab, too, is of an earlier era when fundamental Protestantism was the rule of the land, though his First Mate, Starbuck, finds Ahab to be of a frighteningly blasphemous nature. Note the ornate dialect, almost as if reading from the King James bible, and which makes the passage doubly dramatic.

So far, the discussion relates only to how a central character struggles to express some understanding of a God-based meaning of life, usually falling somewhere within the tenets of written Scriptures of three major monotheistic religions, and on reflections of the character's own life experiences. A big hurdle is that, however inspired the Scriptures may have been, they were written about two thousand years ago and by men of uncertain erudition. Since then, vast amounts of human learning and experience has occurred, but religious dogma, once established, changes only at glacial speed. It might be refreshing to have a few characters express new visions of what a God-based vision of life is for them, where some rational account is taken of the exponential growth of experience and knowledge gained in that two millenniums.

The strange perplexities of quantum mechanics comes to mind as a potential backdrop for new, innovative fiction. A recent NY Times article discusses ongoing confirmations for a proof of entanglement theory in subatomic physics. In essence, subatomic particles, like electrons and photons, have an infinite but measurable range of properties, such as velocity, location, and spin. However, as soon as a measurement is made of a property in one particle of any entangled pair, the entire range of potential properties collapses into finite, correlated values in each of the particles. Experiments demonstrate that this happens no matter the distance introduced between the particles, presumably happening for a distance even to the far side of our universe. Einstein did not like the idea, and he and other major scientists fought it. There was 'the finger of God' aspect in it for them. Nevertheless, the theoretical underpinnings and the experimental data have continued to hold up through today.

What new kind of characterization of God might this prompt in literary fiction writing? Perhaps it might lead to concepts far more sophisticated than the anthropomorphic characterization we presently are constrained with in our stories.

By: RachelM,

on 10/10/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Philosophy,

nothing,

logic,

metaphysics,

reasoning,

existentialism,

*Featured,

Heidegger,

Series & Columns,

Arts & Humanities,

Roy T. Cook,

philosophy puzzle,

Paradoxes and Puzzles with Roy T. Cook,

paradoxes and puzzles with Roy T Cook,

The Yablo Paradox,

Is “Nothing nothings” true?,

necessitism,

Add a tag

In a 1929 lecture, Martin Heidegger argued that the following claim is true: Nothing nothings. In German: “Das Nichts nichtet”. Years later Rudolph Carnap ridiculed this statement as the worst sort of meaningless metaphysical nonsense in an essay titled “Overcoming of Metaphysics Through Logical Analysis of Language”. But is this positivistic attitude reasonable?

The post Is “Nothing nothings” true? appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Alex Guyver,

on 4/12/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

metaphysics,

*Featured,

Arts & Humanities,

Michael Pelczar,

phenomenalism,

Sensorama,

Books,

Philosophy,

perspective,

consciousness,

perception,

Add a tag

We all have experiences as of physical things, and it is possible to interpret these experiences as perceptions of objects and events belonging to a single universe. In Leibniz’s famous image, our experiences are like a collection of different perspective drawings of the same landscape. They are, as we might say, worldlike. Ordinarily, we refer the worldlike quality of our experiences to the fact that we all inhabit the same world, encounter objects in a common space, and witness events in a common time.

The post The world as hypertext appeared first on OUPblog.

With wit and infectious curiosity, Mark Adams takes us on a journey to find Atlantis. He sifts through the evidence, the contradictions, the wild claims of fellow obsessives. What he unearths are the rich jewels of history and lore, as he pays tribute to man's thirst for knowledge. Books mentioned in this post Meet Me [...]

By: Alex Guyver,

on 2/22/2015

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Arts & Humanities,

Form Without Matter,

Mark Eli Kalderon,

philosophy of perception,

Philosophy,

colour,

light,

perception,

metaphysics,

*Featured,

Add a tag

Parmenides, in the Way of Mortal Opinion, envisions the sensible world to be governed by Fire and Night, understood as cosmic principles. As a consequence, Parmenides conceives of the colors as themselves mixtures of light and dark. Parmenides’ view, here, is in line with an ancient tradition dating back at least to Homeric times.

The post The philosophy of perception appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Mohamed Sesay,

on 10/19/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

Philosophy,

Aristotle,

Hume,

metaphysics,

*Featured,

causation,

philosophy of science,

Arts & Humanities,

efficient causation,

Greek philosophy,

philosophical debt,

Add a tag

Causation is now commonly supposed to involve a succession that instantiates some lawlike regularity. This understanding of causality has a history that includes various interrelated conceptions of efficient causation that date from ancient Greek philosophy and that extend to discussions of causation in contemporary metaphysics and philosophy of science. Yet the fact that we now often speak only of causation, as opposed to efficient causation, serves to highlight the distance of our thought on this issue from its ancient origins. In particular, Aristotle (384-322 BCE) introduced four different kinds of “cause” (aitia): material, formal, efficient, and final. We can illustrate this distinction in terms of the generation of living organisms, which for Aristotle was a particularly important case of natural causation. In terms of Aristotle’s (outdated) account of the generation of higher animals, for instance, the matter of the menstrual flow of the mother serves as the material cause, the specially disposed matter from which the organism is formed, whereas the father (working through his semen) is the efficient cause that actually produces the effect. In contrast, the formal cause is the internal principle that drives the growth of the fetus, and the final cause is the healthy adult animal, the end point toward which the natural process of growth is directed.

From a contemporary perspective, it would seem that in this case only the contribution of the father (or perhaps his act of procreation) is a “true” cause. Somewhere along the road that leads from Aristotle to our own time, material, formal and final aitiai were lost, leaving behind only something like efficient aitiai to serve as the central element in our causal explanations. One reason for this transformation is that the historical journey from Aristotle to us passes by way of David Hume (1711-1776). For it is Hume who wrote: “[A]ll causes are of the same kind, and that in particular there is no foundation for that distinction, which we sometimes make betwixt efficient causes, and formal, and material … and final causes” (Treatise of Human Nature, I.iii.14). The one type of cause that remains in Hume serves to explain the producing of the effect, and thus is most similar to Aristotle’s efficient cause. And so, for the most part, it is today.

However, there is a further feature of Hume’s account of causation that has profoundly shaped our current conversation regarding causation. I have in mind his claim that the interrelated notions of cause, force and power are reducible to more basic non-causal notions. In Hume’s case, the causal notions (or our beliefs concerning such notions) are to be understood in terms of the constant conjunction of objects or events, on the one hand, and the mental expectation that an effect will follow from its cause, on the other. This specific account differs from more recent attempts to reduce causality to, for instance, regularity or counterfactual/probabilistic dependence. Hume himself arguably focused more on our beliefs concerning causation (thus the parenthetical above) than, as is more common today, directly on the metaphysical nature of causal relations. Nonetheless, these attempts remain “Humean” insofar as they are guided by the assumption that an analysis of causation must reduce it to non-causal terms. This is reflected, for instance, in the version of “Humean supervenience” in the work of the late David Lewis. According to Lewis’s own guarded statement of this view: “The world has its laws of nature, its chances and causal relationships; and yet — perhaps! — all there is to the world is its point-by-point distribution of local qualitative character” (On the Plurality of Worlds, 14).

Admittedly, Lewis’s particular version of Humean supervenience has some distinctively non-Humean elements. Specifically — and notoriously — Lewis has offered a counterfactural analysis of causation that invokes “modal realism,” that is, the thesis that the actual world is just one of a plurality of concrete possible worlds that are spatio-temporally discontinuous. One can imagine that Hume would have said of this thesis what he said of Malebranche’s occasionalist conclusion that God is the only true cause, namely: “We are got into fairy land, long ere we have reached the last steps of our theory; and there we have no reason to trust our common methods of argument, or to think that our usual analogies and probabilities have any authority” (Enquiry concerning Human Understanding, §VII.1). Yet the basic Humean thesis in Lewis remains, namely, that causal relations must be understood in terms of something more basic.

And it is at this point that Aristotle re-enters the contemporary conversation. For there has been a broadly Aristotelian move recently to re-introduce powers, along with capacities, dispositions, tendencies and propensities, at the ground level, as metaphysically basic features of the world. The new slogan is: “Out with Hume, in with Aristotle.” (I borrow the slogan from Troy Cross’s online review of Powers and Capacities in Philosophy: The New Aristotelianism.) Whereas for contemporary Humeans causal powers are to be understood in terms of regularities or non-causal dependencies, proponents of the new Aristotelian metaphysics of powers insist that regularities and dependencies must be understood rather in terms of causal powers.

Should we be Humean or Aristotelian with respect to the question of whether causal powers are basic or reducible features of the world? Obviously I cannot offer any decisive answer to this question here. But the very fact that the question remains relevant indicates the extent of our historical and philosophical debt to Aristotle and Hume.

Headline image: Face to face. Photo by Eugenio. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr

The post Efficient causation: Our debt to Aristotle and Hume appeared first on OUPblog.

By: RachelM,

on 9/15/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

Books,

ethics,

Philosophy,

physics,

logic,

descartes,

Humanities,

metaphysics,

*Featured,

Physics & Chemistry,

Science & Medicine,

René Descartes,

Cartesians,

Descartes and the First Cartesians,

Frans Hans,

Principles of Philosophy,

Roger Ariew,

the Cartesian System,

Add a tag

René Descartes wrote his third book, Principles of Philosophy, as something of a rival to scholastic textbooks. He prided himself in ‘that those who have not yet learned the philosophy of the schools will learn it more easily from this book than from their teachers, because by the same means they will learn to scorn it, and even the most mediocre teachers will be capable of teaching my philosophy by means of this book alone’ (Descartes to Marin Mersenne, December 1640).

Still, what Descartes produced was inadequate for the task. The topics of scholastic textbooks ranged much more broadly than those of Descartes’ Principles; they usually had four-part arrangements mirroring the structure of the collegiate curriculum, divided as they typically were into logic, ethics, physics, and metaphysics.

But Descartes produced at best only what could be called a general metaphysics and a partial physics.

Knowing what a scholastic course in physics would look like, Descartes understood that he needed to write at least two further parts to his Principles of Philosophy: a fifth part on living things, i.e., animals and plants, and a sixth part on man. And he did not issue what would be called a particular metaphysics.

Descartes, of course, saw himself as presenting Cartesian metaphysics as well as physics, both the roots and trunk of his tree of philosophy.

But from the point of view of school texts, the metaphysical elements of physics (general metaphysics) that Descartes discussed—such as the principles of bodies: matter, form, and privation; causation; motion: generation and corruption, growth and diminution; place, void, infinity, and time—were usually taught at the beginning of the course on physics.

The scholastic course on metaphysics—particular metaphysics—dealt with other topics, not discussed directly in the Principles, such as: being, existence, and essence; unity, quantity, and individuation; truth and falsity; good and evil.

Such courses usually ended up with questions about knowledge of God, names or attributes of God, God’s will and power, and God’s goodness.

Thus the Principles of Philosophy by itself was not sufficient as a text for the standard course in metaphysics. And Descartes also did not produce texts in ethics or logic for his followers to use or to teach from.

These must have been perceived as glaring deficiencies in the Cartesian program and in the aspiration to replace Aristotelian philosophy in the schools.

So the Cartesians rushed in to fill the voids. One could mention their attempts to complete the physics—Louis de la Forge’s additions to the Treatise on Man, for example—or to produce more conventional-looking metaphysics—such as Johann Clauberg’s later editions of his Ontosophia or Baruch Spinoza’s Metaphysical Thoughts.

Cartesians in the 17th century began to supplement the Principles and to produce the kinds of texts not normally associated with their intellectual movement, that is treatises on ethics and logic, the most prominent of the latter being the Port-Royal Logic (Paris, 1662).

By the end of the 17th century, the Cartesians, having lost many battles, ultimately won the war against the Scholastics.

The attempt to publish a Cartesian textbook that would mirror what was taught in the schools culminated in the famous multi-volume works of Pierre-Sylvain Régis and of Antoine Le Grand.

The Franciscan friar Le Grand initially published a popular version of Descartes’ philosophy in the form of a scholastic textbook, expanding it in the 1670s and 1680s; the work, Institution of Philosophy, was then translated into English together with other texts of Le Grand and published as An Entire Body of Philosophy according to the Principles of the famous Renate Descartes (London, 1694).

On the Continent, Régis issued his General System According to the Principles of Descartes at about the same time (Amsterdam, 1691), having had difficulties receiving permission to publish. Ultimately, Régis’ oddly unsystematic (and very often un-Cartesian) System set the standard for Cartesian textbooks.

By the end of the 17th century, the Cartesians, having lost many battles, ultimately won the war against the Scholastics. The changes in the contents of textbooks from the scholastic Summa at beginning of the 17th century to the Cartesian System at the end can enable one to demonstrate the full range of the attempted Cartesian revolution whose scope was not limited to physics (narrowly conceived) and its epistemology, but included logic, ethics, physics (more broadly conceived), and metaphysics.

Headline image credit: Dispute of Queen Cristina Vasa and René Descartes, by Nils Forsberg (1842-1934) after Pierre-Louis Dumesnil the Younger (1698-1781). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The construction of the Cartesian System as a rival to the Scholastic Summa appeared first on OUPblog.

By: Julia Callaway,

on 4/4/2014

Blog:

OUPblog

(

Login to Add to MyJacketFlap)

JacketFlap tags:

History,

Philosophy,

regress,

Plato,

chess,

Aristotle,

Wittgenstein,

thrashing,

Humanities,

metaphysics,

*Featured,

Kant,

Gottlob Frege,

Graham Priest,

history of philosophy,

Nāgārjuna,

paraconsistent logic,

western philosophy,

pheidippides,

fruitfully,

Add a tag

By Graham Priest

If you go into a mathematics class of any university, it’s unlikely that you will find students reading Euclid. If you go into any physics class, it’s unlikely you’ll find students reading Newton. If you go into any economics class, you probably won’t find students reading Keynes. But if you go a philosophy class, it is not unusual to find students reading Plato, Kant, or Wittgenstein. Why? Cynics might say that all this shows is that there is no progress in philosophy. We are still thrashing around in the same morass that we have been thrashing around in for over 2,000 years. No one who understands the situation would be of this view, however.

So why are we still reading the great dead philosophers? Part of the answer is that the history of philosophy is interesting in its own right. It is fascinating, for example, to see how the early Christian philosophers molded the ideas of Plato and Aristotle to the service of their new religion. But that is equally true of the history of mathematics, physics, and economics. There has to be more to it than that—and of course there is.

Plato, Museo Pio-Clementino, Vatican

Great philosophical writings have such depth and profundity that each generation can go back and read them with new eyes, see new things in them, apply them in different ways. So we study the history of philosophy that we may do philosophy.

One of my friends said that he regards the history of philosophy as rather like a text book of chess openings. Just as it is part of being a good chess player to know the openings, it is part of being a good philosopher to know standard views and arguments, so that they can pick them up and run with them.

There is a lot of truth in this analogy, but it sells the history of philosophy short as well. Chess is pursued within a fixed and determinate set of rules. These cannot be changed. But part of good philosophy (like good art) involves breaking the rules. Past philosophers may have played by various sets of rule; but sometimes we can see their projects and ideas can fruitfully (perhaps more fruitfully) be articulated in different frameworks—perhaps frameworks of which they could have had no idea—and so which can plumb their ideas to depths of which they were not aware.

Such is my view anyway. It is certainly one that I try to put into practice in my own teaching and writing. I find that using the tools of modern formal logic is a particularly fruitful way of doing this. Let me give a couple of examples.

One debate in contemporary metaphysics concerns how the parts of an object cooperate to produce the unity which they constitute. The problem was put very much on the agenda by the great 19th century German philosopher and logician Gottlob Frege. Consider the thought that Pheidippides runs. This has two parts, Pheidippides and runs. But the thought is not simply a list, <Pheidippides, runs>. Somehow, the two parts join together. But how? Frege’s answer (we do not need to go in the details) ran into apparently insuperable problems.

Aristotle went part of the way to solving the problem over two millenia ago. He suggested that there must be something which joins the parts together, the form (morphe), F, of the proposition. But that can be only a start, as a number of the Medieval European philosophers noted. For <Pheidippides, F, runs> seems just as much a list as our original one, so there has to be something which joins all these things together—and we are off on a vicious infinite regress.

The regress is broken if F is actually identical with Pheidippides and runs. For then nothing is required to join F and Pheidippides: they are the same. Similarly for F and runs. But Pheidippides and runs are obviously not identical. So identity is not, as logicians say, transitive. You can have a=b and b=c without a=c. It is not clear that this is even a coherent possibility. Yet it is, as modern techniques in a branch of logic called paraconsistent logic can be used to show. I spare you the details.

A quite different problem concerns the topic in modern metaphysics called grounding. Some things depend for their existence on others. Thus, a chair depends for its existence on the molecules which are its parts; these, in turn, depend for their existence on the atoms which are their parts; and so on.

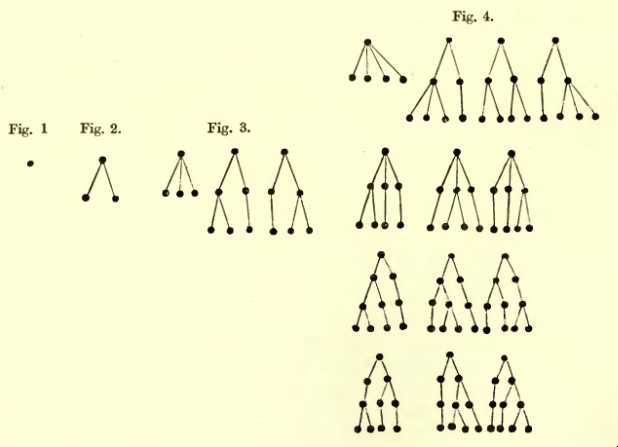

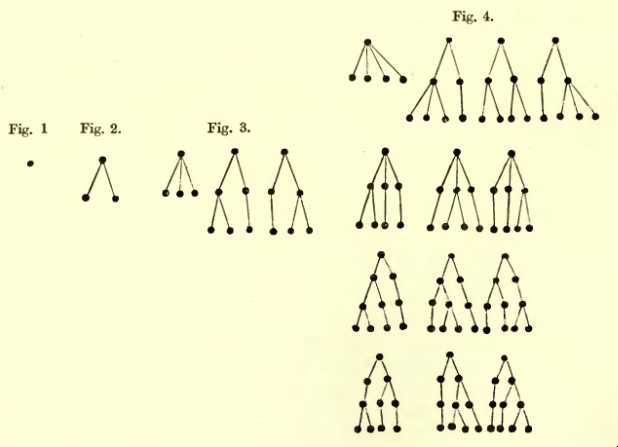

It contemporary debates, it is standardly assumed that this process must ground out in some fundamental bedrock of reality. That idea was attacked by the great Buddhist philosopher Nāgārjuna (c. 2c CE), with a swathe of arguments. Ontological dependence never terminates: everything depends on other things. Again, it is not clear, Nāgārjuna’s arguments notwithstanding, that the idea is coherent. If everything depends on other things, we have an obvious regress; and, it might well be thought, the regress is vicious. In fact, it is not. It can be shown to be coherent by a mathematical model employing mathematical structures called trees, all of whose branches may be infinitely long. Again, I spare you the details.

Of course, in explaining my two examples, I have slid over many important complexities and subtleties. However, they at least illustrate how the history of philosophy provides a mine of ideas. The ideas are by no means dead. They have potentials which only more recent developments—in the case of my examples, in contemporary logic and mathematics—can actualize. Those who know only the present of philosophy, and not the past, will never, of course, see this. That is why philosophers study the history of philosophy.

Graham Priest was educated at St. John’s College, Cambridge, and the London School of Economics. He has held professorial positions at a number of universities in Australia, the UK, and the USA. He is well known for his work on non-classical logic, and its application to metaphysics and the history of philosophy. He is author of One: Being an Investigation into the Unity of Reality and of its Parts, including the Singular Object which is Nothingness.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only philosophy articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Images: Bust of Plato, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. Image of a graph as mathematical structure showing all trees with 1, 2, 3, or 4 leaves, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Philosophy and its history appeared first on OUPblog.

Some writers have only the barest of concepts in mind as they commence a first draft of a story; others prefer to work with a written outline, listing perhaps main characters, the principal and secondary problems, interim resolutions of secondary problems along the way, and a final resolution. Another idea is to engage the left brain in the conceptual process, and develop a story board before proceeding into the first written draft. The graphics needn't be elaborate, perhaps using only stick figures for characters and very rough sketches for the rest, but it may stir the imagination and help visualize the sequence of key scenes that are most dramatic in telling the story. The story board might also alert the writer to how well the arc of tension rises through the story toward some inexorable release in a final resolution of the main problem.

Story boards are most often considered for developing the very short stories of children's picture books, but they can, and have been, used for considering the skeletal structure of longer fiction, including novels. Whereas the story board might contain a graphic treatment for every page in a child's picture book, it might only show a panel for each major change of setting, or each complication, in the longer forms of fiction.

The partial story board shown above relates to my short story tentatively called, The Summit, which is currently being revised. The story opens (1) with the three characters, an older scientist, his much younger lover, an engineer, and a local guide. They are climbing a mid-difficulty peak in northern India. Their position is precarious, having just survived an avalanche, the westerners are resorting to supplemental oxygen, and the story needs to get moving. In (2) they face the next challenge on this lesser known route--a steep escarpment requiring some technical climbing. It seems important not to get bogged down in details here, but to just show the harrowing conditions. In (3) the climbers take refuge in a small cave on the face to escape worsening weather conditions. To pass time, the scientist draws his companions into a topic much on his mind, the existence of god. He's prone to dismiss it as myth, but seems apprehensive of newer complexities uncovered by science that may touch on it. The engineer offers one of the elementary theological arguments for god, but has little interest in the subject. She has more immediate concerns--what to do about a recently discovered pregnancy, and an intuition that the relationship is almost over. The guide simply makes them aware he is a devotee of Kali. Of course, there's not time to delve very deeply into the god or personal issues, but the idea is to show a state of mind that sets a course for what follows. As soon as the weather breaks a bit, the climb resumes. In (4) the route taken encounters a deep slipped-out region of rock, called 'the notch,' which they must cross on their path to the summit. The guide disappears during the crossing, and is assumed to have fallen into a crevice somewhere in the notch.

The complete story board for this short story is 8 panels total, and was done to aid the revision process. The blog for next mont